Isabela Grosseová: Restoring Dignity

Introduction

“Mr. J. is an exceptional person. He knows how to talk to children and is able to engage people. They listen to him. He knows how to gain their respect. He exudes optimism. But when he speaks about his youth and school, you can hear a certain bitterness in his voice. He gradually lost touch with his peers at the atelier. He watches cultural programs on Czech TV Art, and when he by chance sees a former schoolmate in a program, he comments on their appearance out loud with sarcastic, and usually, accurate remarks. He also knows how to imitate them in a comedic way. David, Mainer or Střížek. He doesn’t like to show the sketches he did in school. When you ask him about them, he guides the conversation to another topic, or he tells you he doesn’t wish to talk about himself.

Almost immediately after the revolution, Mr. J. started up one of the first IT companies here. But still today he claims that he knows nothing about computers. He could have allegedly started an advertising agency like many of his friends at the time, but he was impressed by computers and how it was not yet possible to imagine just what all they would be capable of doing. During 20 years he allegedly did not have to bribe or corrupt anyone, and despite this his company became one of the twenty most successful in the industry. When you ask him how he has been able to become so successful, when he knows nothing about computers, he answers that he doesn’t know how to explain it: he always contemplates everything "organically." "I don’t think about the thing itself but about the background. Each problem lies on something or stands before something and is explained by something. So, I don’t sort it out by devoting time to it directly. I give all my attention to the surroundings – the light and the background." When Mr. J. speaks about his approach to work, he uses words that he learned as a student at Academy of Fine Arts.”

The excerpt above from my 2014 exhibition Competence (together with J.Alvaer and J.Ptáček), at the Fotograf Gallery in Prague, may serve as an introduction to my project. It captures the (neo-liberal) mystery of artistic education, which, paradoxically, does not lead to becoming a "famous" artist, but nonetheless becomes a nourishing background for other activities entirely or partly independent of art. I suggest, this is a fundamental question: What happens to artistic competence, in the end, when artists put their sensibilities into other activities. What is interesting about this formation, and why are we voluntarily still part of the invisible dark matter of transitory artworlds?

Project Statement

Writing from the position of being a PhD student at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, I address the subject of competences in artistic education in my dissertation. My aim is to give insight into the experiences of graduates of the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, and to evaluate the impact of this education on their lives.

Using a sample of 50 interviews with now older graduates, (I personally conducted all these interviews during the last 3 years), I want to show the potential of this education, if, for whatever reason, the interviewed subject did not find personal fulfillment by becoming a professional artist, and thereby realizing his or her life expectations.

The justification for this thesis is the need to describe the feelings associated with "failure" in the artistic environment. If I assume a sense of being excluded, not having exhibitions and not finding professional success entails feelings of bitterness and disapointment, how exactly are those emotions talked about by those experiencing them?

I deal with the following questions: Is it possible to view the resignation from an artistic career as positive in some cases? Is it possible to imbue the non-artistic world with artistic competence?

My ambition is to contribute to possible changes and improvements of art education in the Czech Republic. In relation to my research, I am as well looking for ways how to implement some of my findings back into the discussion on artistic and aesthetic education.

During my three years of work and collection of material, I have defined several theses, and it is one of these that I would like to better translate and describe in theoretical language and forms. I call this thesis: Restoring Dignity.

Restoring Dignity

I am interested in what it meant for many graduates to work as restorers. I looked at the Academy of Fine Arts graduates' experience through the prism of feminism, and I found what was, for me, a very surprising and supportive structure of how to perceive restoration in relation to dignity and, consequently, in relation to subordinating one’s own artistic competence to patriarchal cultural heritage. To accept restoration work as a source of income was, and is, a very common way to remain in the art sphere, if there is no other opportunity to support oneself with activities associated with one’s own (personal) art practice.

In the 1970s and 1980s it was common for graduates in art to earn money as restorers. Painters restored historical paintings, sculptors restored statues. These historical artworks were owned by the communist state, and the work was performed throughout the Czechoslovakia. The Union of Czech and Slovak Fine Artists, whose committee was prosaically headquartered in the Mánes Gallery building in Prague, assigned work to fine arts artists and did not require any license. It seems that the practical skills of artists were thus deliberately used to "occupy" art school graduates in some way. On the one hand, this made it possible for them to earn a living, on the other hand, the intensity of work over a period of a few months completely pulled them from their own context, especially if it was necessary to relocate somewhere for the duration of the work. This seemingly related field controlled and pacified many potential artists.

As a restorer, a person could apply all practical technological skills, which, however, made it necessary to suppress their own personality and invention.

It is obvious that if it is necessary to suppress something within yourself repeatedly for a long time, it will affect your self-confidence. Restoration is a very passive service to the cultural heritage, and in general, it paralyzes an otherwise free-minded spirit. From a feminist point of view, this institutional subjection of only certain qualities of a person, and demanding complete submission, has insidious consequences.

Over time, and on a personal level, it is basically about the treatment of psychological injury (intrapsychic loss), as a method of healing, which aims to rehabilitate a person with a healthy sense of professional integrity. A graduate of fine art leaves a school with an extremely individualistic approach to art, making that person vulnerable if there is no interest in his or her work. Working as a restorer dampens this individualism and leads to transformation into the position of more of a “guild” artist, as we know these from the past. This involves switching to another type of existence as an artist. However, for some, this position is sufficiently stimulating, while for others it is constricting with the feeling of resignation. This opens another theme: Resignation through restoration.

Research exhibition: "I Did Not Care About the Exhibitions"

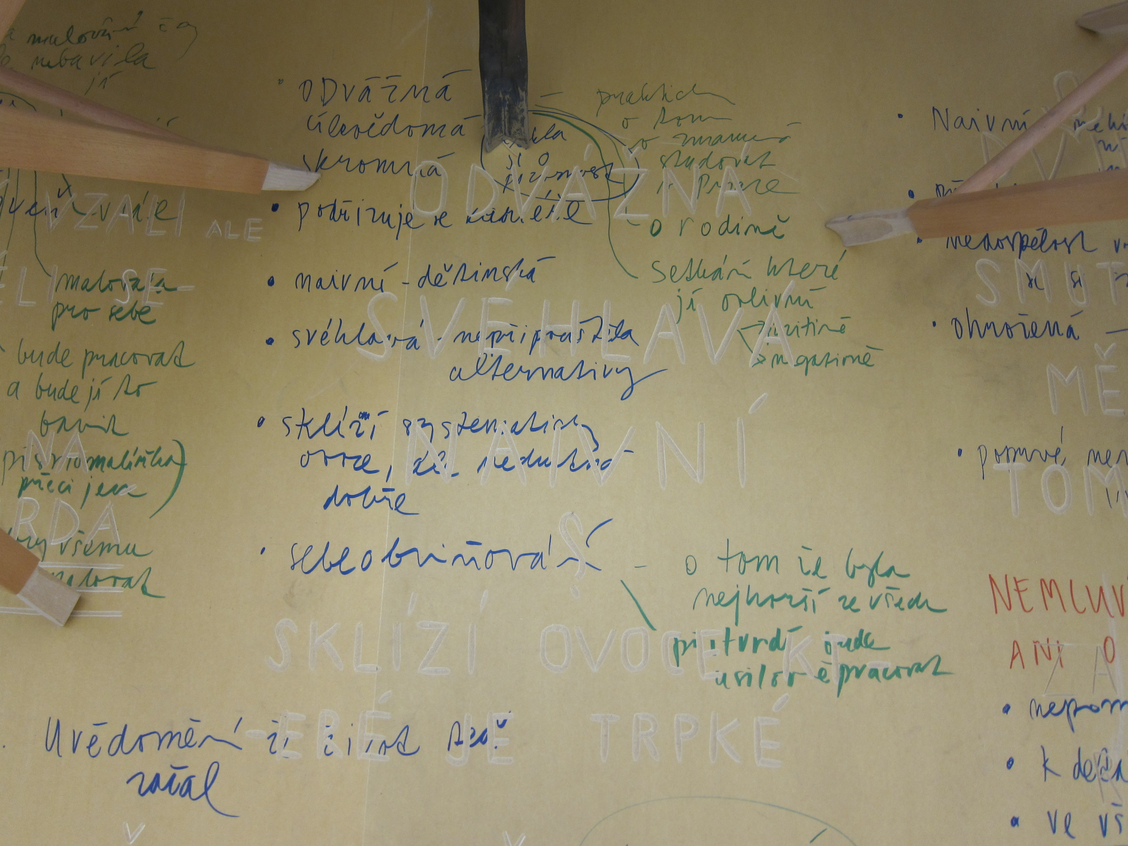

The exhibition is a backdrop on which several “blind panels” took place based on the Biographical Narrative Interpretation Method (BNIM). It was an interpretation process with about six to eight panelists around the table.

The text we worked with was the testimony of the person who graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts. The panelists didn’t know the material. The recording of the conversation was rewritten and read step by step without the knowledge of what will come next, how the narrative will evolve.

After each sequence of the read text, we talked about the experience-hypothesis. What is experienced by the person who told his life at that particular moment? Then, after imagining about five speculative hypotheses, we marked for each of them about five paths of a possible continuation of the narrative.

For example, if this person experiences a sense of serenity when she talks about this event, what will she be talking about now? Or if she is disappointed, how will she continue, what will happen next? In the process of gradual assumptions and projections, the image was corrected, refined.

For myself, this blind panel helped me to see connections I have not noticed or I have not thought about.

The objects in the gallery are Medium, Resource, Tool and their Allegories. A lively experience is then what has gradually been contemplated and inscribed in this space.

About projection:

Three videos projected on a sheet of paper held by the viewer. I have asked three different absolvents of the Academy who graduated from fine art, but have been restoring historical artworks as a job all their life, to take me to the location of one such as restored works.

Then I asked them to try to remember how was it at that time and if they could show me how they did it. Afterwards, we came to a pantomimic reconstruction of the work process. On the projection, we see their hands working. Restoration tools are imaginary.

I was wondering at what point this my request would become something that they would take as a means of return to the time they restored the work. And what this experience will bring.

"Resignation through restoration".

Sound recording on headphones.

The theme of the audio is this: Many of the graduates of the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague have become restorers over time and gave up art making. If we consider resignation by restoration, the question remains what is actually restored, history, fresco, or our own dignity?