The quality of the arpeggi of Llobet very often leave the impression, that they are based on a relaxed, perhaps "careless" (and thus often erraticly accented) right hand that allowes the hand to droop into the strings with a wrist angled to around 90 degrees. The usually uneven internal timing of the fast arpeggi suggests, that Llobet often employs a thumb that in a rapid, "falling" gesture strucks multiple strings in a quick succession.

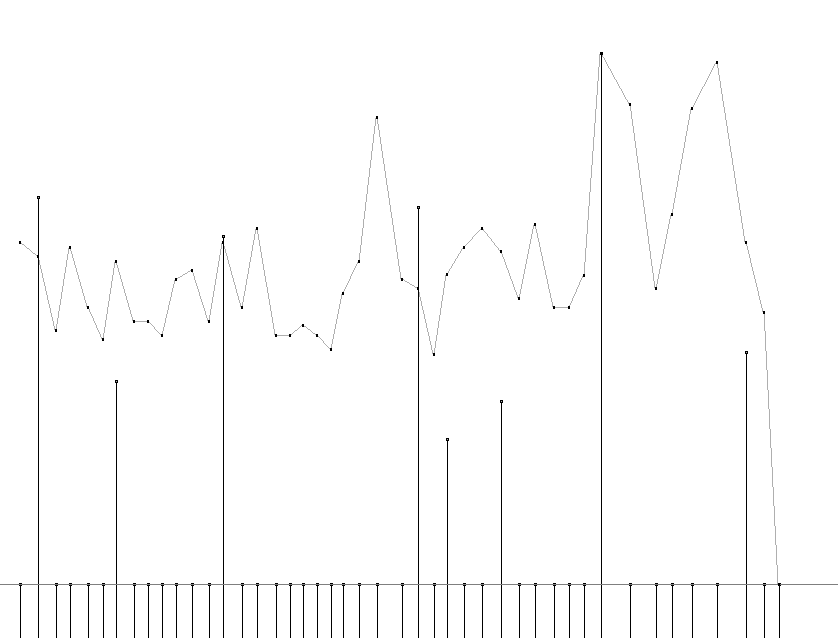

After around 20 attempts to adapt myself to the mentioned traits of Llobet's playing – expanded and slowly arpeggiated or dislocated first beats, shortened and quickly arpeggiated second beats, a hand relaxedly and rapidly "falling" into the strings – the result sounds like this:

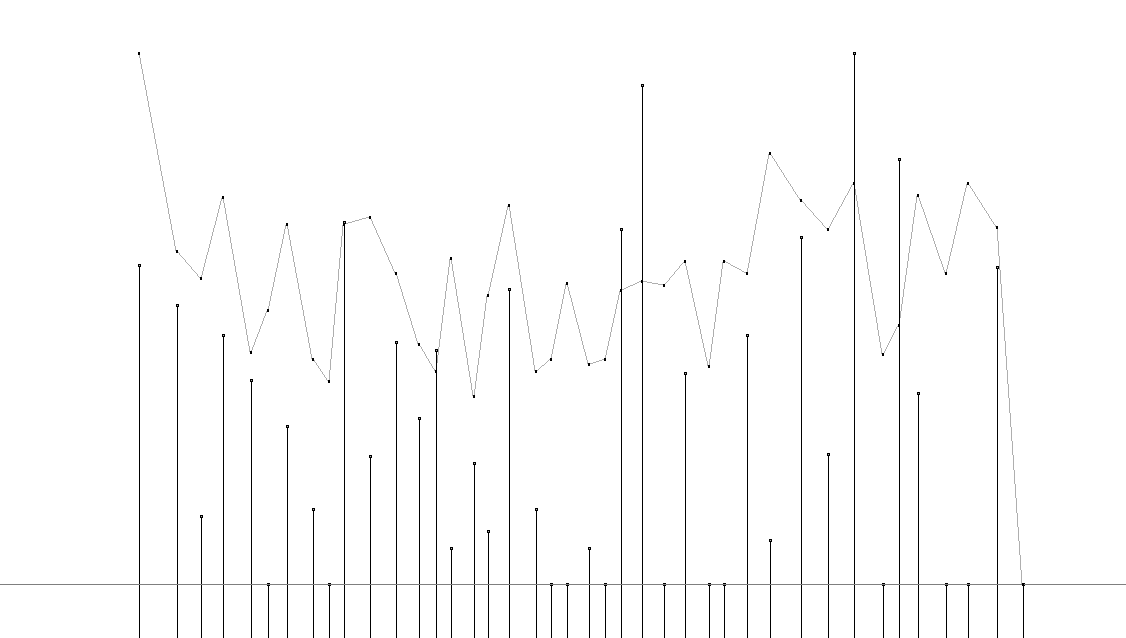

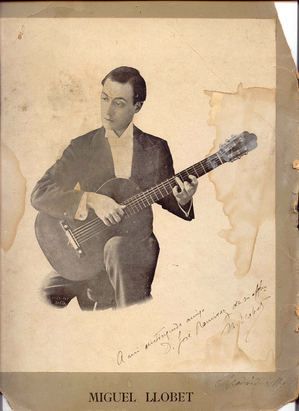

Miguel Llobet plays El Testament d'Amelia, 1925. Stems give the length of arpeggio or dislocation, the connected dots give the duration of the quarter-notes.

This video shows the performance of Miguel Llobet. The longer a stem, the more time the arpeggio takes.

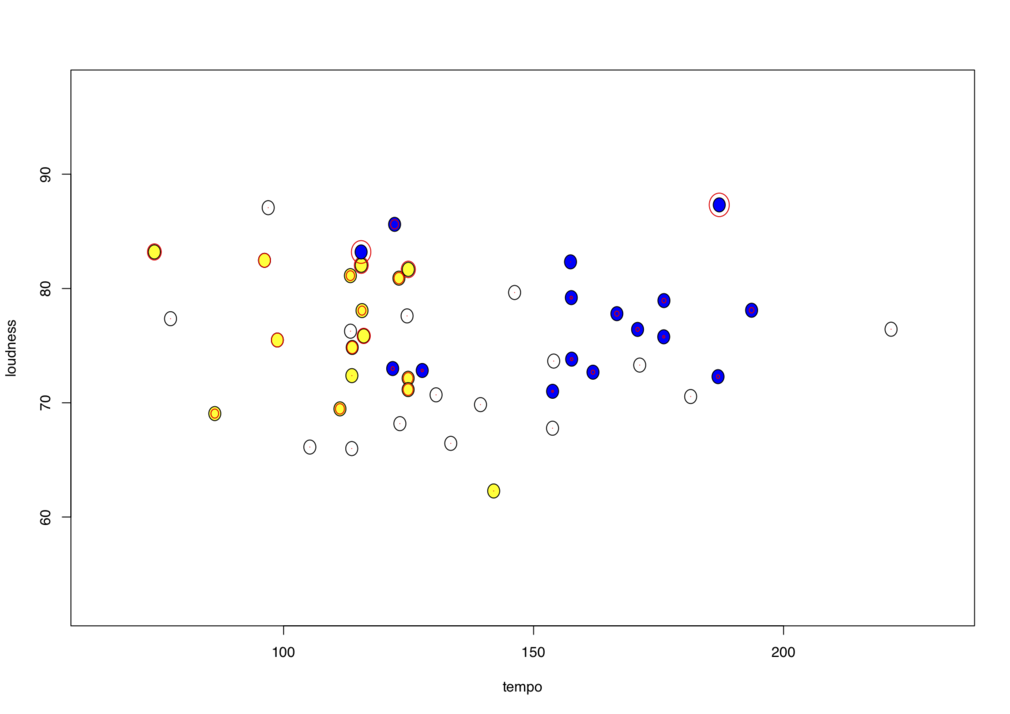

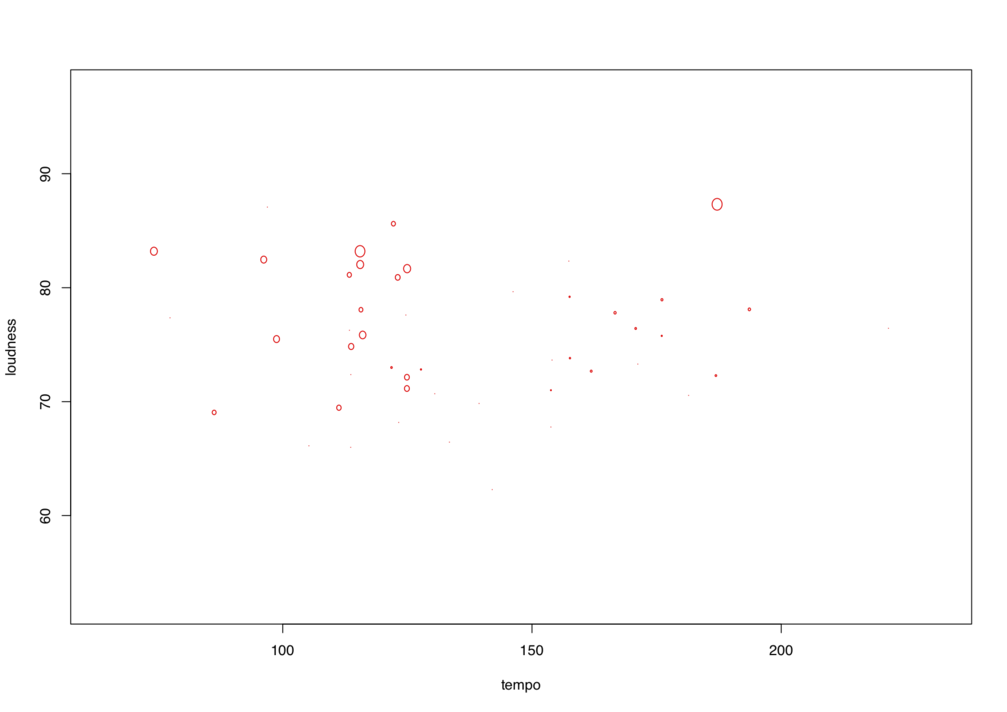

There is a clear correlation between duration and arpeggio length: The slower a beat is played, the longer the arpeggio is. The horizontal axis shows tempo, the vertical axis loudness.

2. The first beat of a bar is always played slow (yellow circles), the second beat (blue circles) is always played fast, while the third beats (white circles) can be longer or shorter. Slow arpeggiation occurs on the first beat, fast arpeggiation on the second, the third beat is never arpeggiated. Only in one case, measure 5, a fast (and loud) second beat is also long arpeggiated.