Arpeggiation gives the different cycles (and in a less clear way also the phases) a characteristic starting point.

Where is the accent?

Let's consider a jumping ball. There are two phases: the ground touching and the flying phase. Depending on how soft the ball is, two phases can be differentiated in the „ground touching“ phase: „entrance“ and „exit“. At the same time, there’s a characteristic „course of tension“: as we see the ball flying, the expectation of the coming bounce let’s the tension grow. The grown tension „discharges“ in the moment of hitting the ground. An arpeggio can represent those three phases: It can arrive on the final note, it can have a starting impulse from the first note or it is simply "softening" one chord as a unity.

Neal Peres da Costa sees the playing of Reinecke as a combination of a "type 2" arpeggio and a dislocated melody note.

Alan Dodson showed in his article "Expressive Asynchrony in a Recording of Chopin's Prelude No. 6 in B Minor by Vladimir Pachmann" that dislocation can be used as a device to mark the downbeats in music that implies a metrical shifting of the accents.

Regarding Reinecke's obviously regular use arpeggiation, Daniel Leech-Wilkinson raises the question, if the practise of arpeggiation in connection with the habit of delaying the melody note, might be pointing us to a much older tradition:1

"Most chords are arpeggiated upwards, so consistently that one wonders whether this is harpsichord technique surviving into nineteenth-century playing, or nineteenth-century pianism applied to Mozart. The notes of the melody are almost always delayed, sometimes by as much as 1/5 of a second, which may not sound very much but, when one is used to notes placed vertically in a score being played exactly together, seems a very long time as one listens. […] In Reinecke’s case, the regularity of the arpeggiation and of the accompaniment beat lead us strongly to the sense that the melody is late rather than the bass early, and that too tends to increase the sense of alienation for a modern listener, who is at least familiar with the idea of a low bass note sounding early when an impossible stretch forces it. Reinecke’s playing can’t be explained away like that, and the fact that he is playing Mozart, for us such a regular composer, simply makes the strangeness of his playing more acute. The thought that there might be a historical cause in his youth is almost frightening because of the wholesale rethink it would force about everything we imagine as Classical."

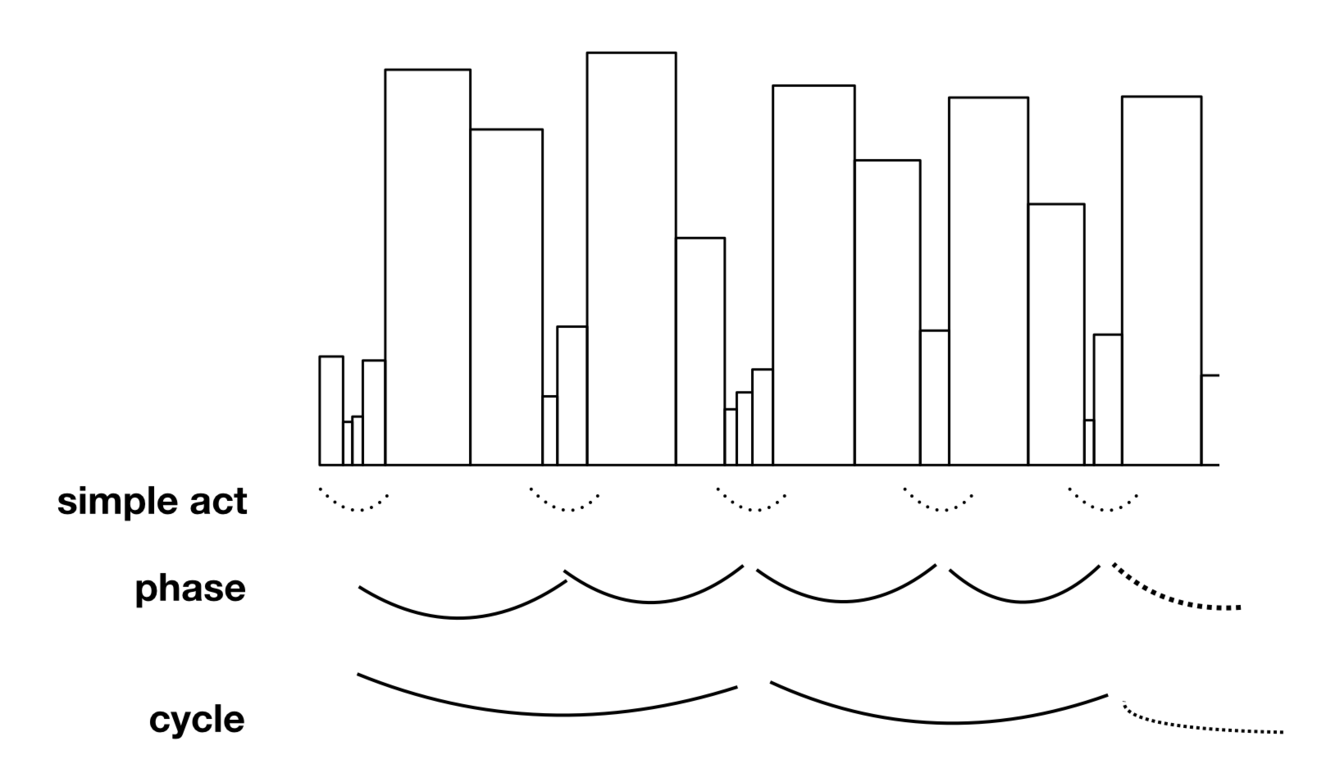

Interesting here is that on a larger-scale we observe that Reinecke makes frequent use of arpeggiation to bring out a clearly structured meter. The following illustration shows Reineckes "structured" use of arpeggiation labeled with terms introduced by Hermann Gottschewski. Given the amount of tempo inflection Reinecke is using, arpeggiation is simply used to mark the downbeats.

In the lower illustrations real time is being represented by both, horizontal and vertical axis. The higher (and proportionally wider) a beam, the more time is being given to the corresponding note by the performer.

It is to be noted that the forms that are recognizable in visualizations as the given ones are hard to be heard when playing the audio at normal speed. Half or even quarter speed is required to make the difference audible.

Here the beginning of a rather early (1904) piano roll recording of Carl Reinecke – born in 1824 and thus representing a 19th century performance style – playing the second movement of a Mozart concerto should be analyzed.1

First we note that Reinecke uses different shapes of the arpeggio-internal timing (-> play gesturally).

1 This recording has been studied already various times, mostly regarding Reineckes significant use of tempo modification. See e.g. Robert Hill, "Carl Reinecke's Performance of Mozart's Larghetto and the Nineteenth-Century Practise of Quantitative Accentuation", in: G. Butler, G. Stauffer, M. Greer (edd.), About Bach, Urbana 2008, pp. 171–180 and Hermann Gottschewski, "Tempoarchitektur – Ansätze zu einer speziellen Tempotheorie", Musiktheorie, 8(2), pp. 99–117 .

1 Daniel Leech-Wilkinson, The Changing Sound of Music: Approaches to Studying Recorded Musical Performance, Ch. 6 ¶24.

see H. Gottschewski, Logarithmic timing (accessed at 10.12.2017) for explanation of this timing model