Thereafter I have tried to apply those rules to my own playing of the chorale. This is what the first try sounded like:

Which sounds as follows (played twice: first in a strong rubato-manner, subsequently in a more synchronized way for comparison):

What happened?

- agogical lengthening of beginning, middle and end of the phrase

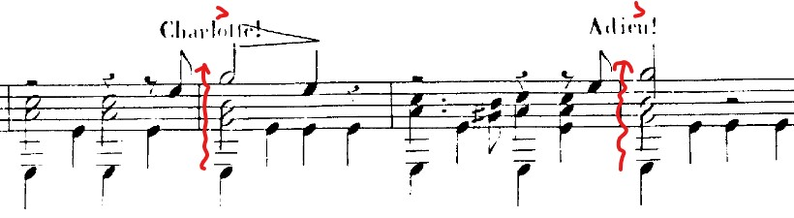

- two times melody before accompaniment, otherwise always melody after. Only the final phrase note played together with accompaniment

- The accompaniment 32nd-note figure seems fairly regular in timing, except for the 2nd and 3rd beat in bar 1, which is at the same time most dense and "exciting" place

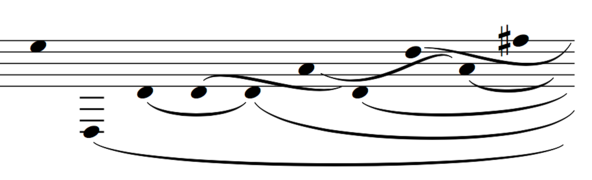

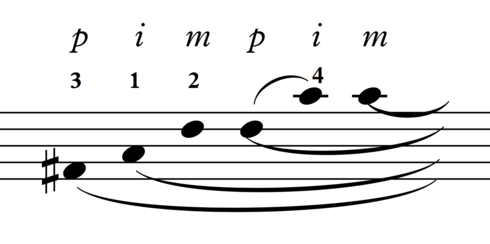

Another common device for arpeggiation on baroque guitar as well as theorbo is to pull backwards the index finger through multiple strings. Combined with the effect of imitating a reentrant tuning, the same arpeggio of the above sound example is as follows:

What did happen when simulating the arpeggio of this bar to be actually played be two different persons?

Another idea is the imitation of the reentrant tuning of a theorbo. Prominent feature is the non-linearity of arpeggiation as a result of this reentrant tuning.

Especially for the last chords of the fast movement of this Froberger partita the pulled index seems to create an interesting effect referencing the sound of a baroque guitar:

A picture of Miguel Llobet clearly showing his right hand position. This position was preferred by Francesco Tarréga, Llobet's teacher. Andrés Segovia also used it.

Another example from Chopin's Prelude op. 28 No. 7 (arranged by Francesco Tarregá). The effect of connecting the upbeat with the following downbeat in bar 1 is reached by placing the accompanying a slightly before the downbeat.

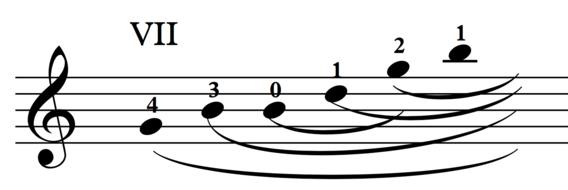

transformed (and for technical reasons transposed to D major) to a hypothetical version for two independent players:

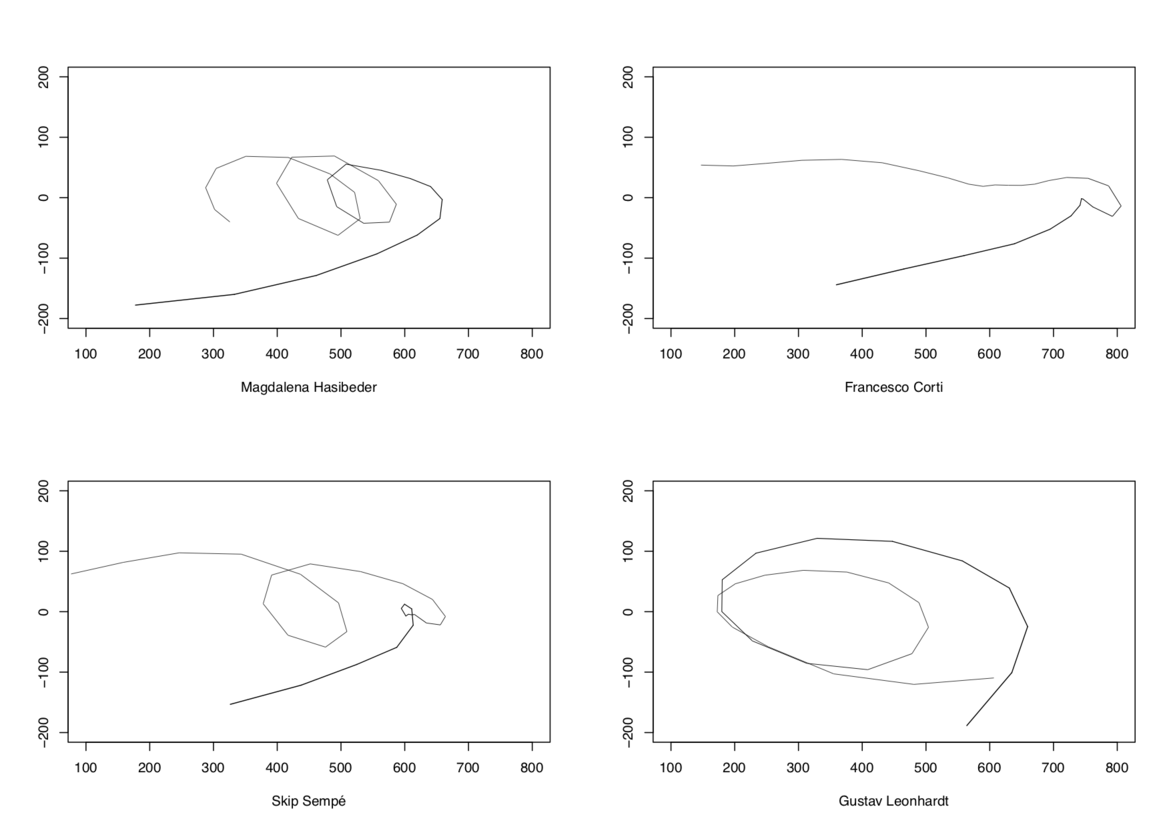

The recordings are played in the following order: (1) Hasibeder, (2) Francesco Corti, (3) Skip Sempé, (4) Gustav Leonhardt

Girolamo Frescobaldi, Toccate e partite d'Intavolatura, Rome: Niccolo Borbone, 1616. Translated by Christopher Sternbridge and Kenneth Gilbert (edd.), Kassel: Bärenreiter 2010.

6 David J. Buch, "'Style brisée', 'Style luthée and 'Choses luthées", MQ Vol. 71 No. 1 (1985), p. 57f.

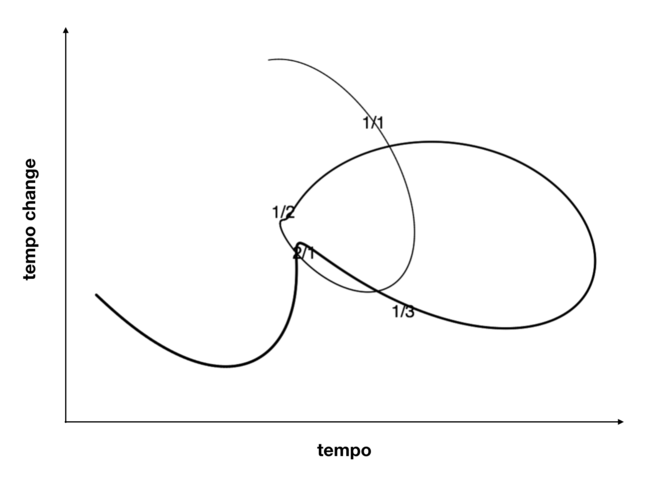

This recording has been studied already various times, mostly regarding Reineckes significant use of tempo modification. See e.g. Robert Hill, "Carl Reinecke's Performance of Mozart's Larghetto and the Nineteenth-Century Practise of Quantitative Accentuation", in: G. Butler, G. Stauffer, M. Greer (edd.), About Bach, Urbana 2008, pp. 171–180 and Hermann Gottschewski, "Tempoarchitektur – Ansätze zu einer speziellen Tempotheorie", Musiktheorie, 8(2), pp. 99–117 .

2 Daniel Leech-Wilkinson, The Changing Sound of Music: Approaches to Studying Recorded Musical Performance, Ch. 6 ¶24.

1 cf. Johannes Monno, Die Barockgitarre: Darstellung ihrer Entwicklung und Spielweise, München 1995.

1Luigi Tagliavini, "L'Arte di «non lasciar vuoto lo strumento»: Appunti sulla prassi cembalistica italiana nel Cinque e Seicento", Rivista Italiana di Musicologia Vol. 10 (1975), p. 375. see also Diruta Il Transilvano I, f. 6: “[…] quello stesso effetto, che fa il fiato nel Organo, nel tener l’armonia, bisogna che fate fare all’Istrumento da penna; Et per eßempio, quando sonate nel Organo vna Breue, over Semibreve non si sente tutta la sua armonia senza percuotere più d’una volta il Tasto: ma quando sonarete nell’ Istrumento da penna tal note li mancherà più della metà dell’armonia: bisogna dunque con la viuacità, & destrezza della mano supplire à tal mancamento con percuotere più volte il Tasto leggiadramente.”

2Jean-Jacques Rousseau, "Volume 9. Dictionnaire de musique", in: Collection complète des oeuvres, Genève, 1780-1789, vol. 9, in-4°, online edition at www.rousseauonline.ch, last accessed 3.3.2019. p. 27.

3 Anselm Gerhard, "'You do it!'. Weitere Belege für willkürliches Arpeggieren in der klassisch-romantischen Klaviermusik", in: Zwischen schöpferischer Individualität und künstlerischer Selbstverleugnung.Zur musikalischen Aufführungspraxis im 19. Jahrhundert, ed. by Claudio Bacciagaluppi, Roman Brotbeck und Anselm Gerhard, Schliengen 2009 (Musikforschung der Hochschule der KünsteBern,Bd.2),S.159–168, here: p. 160

4 A typical comparison of the construction of modern pianos vs. historical fortpianos and the implications for the interpretation can be found in Clauda de Vries, Die Pianistin Clara Wieck-Schumann. Mainz 1996, p. 59–67. Unfortunately she describes the development of keyboard instruments as a history of constant improvement which might be reconsidered. Similiar observations can be made for the development of the classical guitar.

7 Perrine, Pieces de Luthé en musique, Paris 1680, p. 5, cited by David J. Buch, "'Style brisée', 'Style luthée and 'Choses luthées", MQ Vol. 71 No. 1 (1985), p. 58.

This is the second movement of the Krönungskonzert by Mozart (listen to it here)

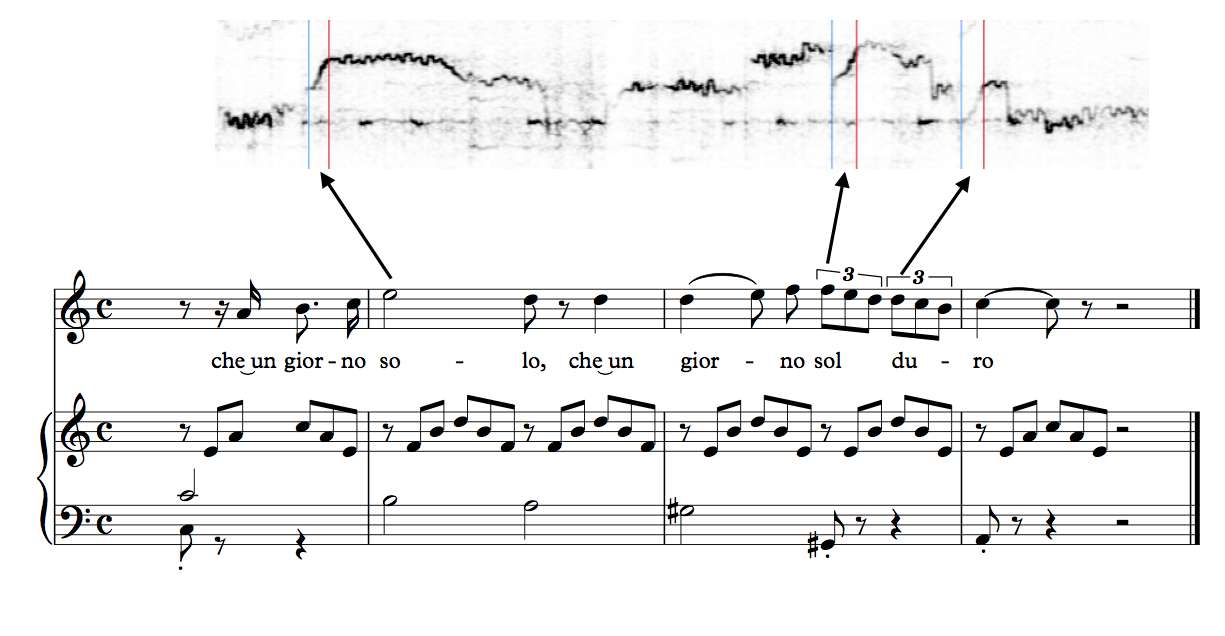

The left graph shows an extract of the spectrogram of Patti singing. The vertical axis shows the frequencies (from wich the pitch becomes obvious) with all it's fluctuations and the horizontal axis shows time.

This is a recording of the "London Derry", played by David de Groot, violin, D. Bor, piano, H. M. Calvé, violoncello. Recorded in 1929. Found here.

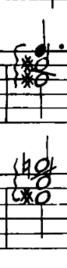

I have been conducting an experiment in which I tried to play with all the possible permutations of the notes of a chord. Though I would consider this experiment to be failed, it is documented here.

1 Already Domenico Corri describes this to be the main point of the portamento (The Singer's Preceptor, London ca. 1810, p. 3f.): "Portamento di voce is the perfection of vocal music; it consists in the swell and dying of the voice, the sliding and blending one note into another with delicacy and expression". For further discussion see Jesper Bøje Christensen, "Was uns kein Notentext hätte erzählen können: Zur musikalischen Bedeutung und Aussagekraft historischer Tondukumente", in: Claudio Bacciagaluppi et al. (edd), Zwischen schöpferischer Individualität und künstlerischer Selbstverleugnung: zur musikalischen Aufführungspraxis im 19. Jahrhundert. Vol. 2. Edition Argus, 2009. p. 146.

1 the most in-depth study of this topic has been done by Hermann Gottschewski, Interpreation als Kunstwerk, Laaber 1996. Also Neal Peres da Costa, Off the Record, Oxford 2012 thoroughly discusses the question of piano rolls.