4. THE COURANTE IN FRENCH SEVENTEENTH CENTURY HARPSICHORD MUSIC

The Courante Françoise is the most common dance type in harpsichord music from the seventeenth century in France (there are more than one hundred ten Courantes between the dances composed by Chambonnières, Louis Couperin and d’Anglebert). In a traditional sequence of a Suite of dances, we can find two, three or even more Courantes. The Courante was not only the most common dance in the harpsichord music, but it was also the most prevailing dance in lute music, in chamber and in orchestral music. A remarkable example is the “Manuscript of Cassel” with Suites published by Jules Écorcheville, which contains more than two hundred pieces for three, four or five voices and fifty four of them are Courantes.

The absence of musical sources of French harpsichord music in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries has encouraged a number of conjectures about the evolution of French keyboard style before Chambonnières.

4.1. The influence of the Lute repertoire in the French keyboard tradition:

During the last decades of the sixteenth century and the first half of the seventeenth century, there is a generation of composers and lutenists who prepared the way for the music of the three great masters of the harpsichord music in France in the second half of the seventeenth century. These lutenists and composers, like René Mézangeau (c. 1568 - 1638), Ennemond Gaultier (c. 1575 - 1651), Robert Ballard (c. 1572 - 1650), Nicolas Vallet (c. 1583 - c. 1642), Pierre de La Barre (1592 - 1656), Germain Pinel (c. 1600 - 1661), Étienne Richard (c. 1621 - 1667), developed their own style for the lute. All these composers wrote, mainly, dances for lute (Allemandes, Courantes and Sarabandes), and we can see in these pieces one of the origins of the French Harpsichord Suite.

The lute’s popularity in France could explain why so little keyboard music was published in France during the sixteenth century. It seems normal, that when the French harpsichordists began to develop their own writing, they would look for inspiration into the lute music, which was considered at that time, “the noblest instrument of any”. Harpsichord composers adopted lute effects directly incorporating them into the technical resources of their own instrument.

The Courantes for lute of the first half of the seventeenth century frequently derive their melodic lines from dances or airs de cour, and they have the clearly defined phraseology and melodic contour of dance music. Since the Courante as a genre is present in sources throughout the period, this shift in orientation away from melody towards the manipulation of abstract formulae is clearly traceable. Later Courantes show a move from crotchet to quaver movement, implying an increase of brisure.

An important characteristic of the seventeenth century French harpsichord and lute repertory in general is the use of asymmetrical phrases, syncopations, anticipations and delays of the music in all voices, and the use of the typically French Inègal notes.

4.2. Music for Clavecin:

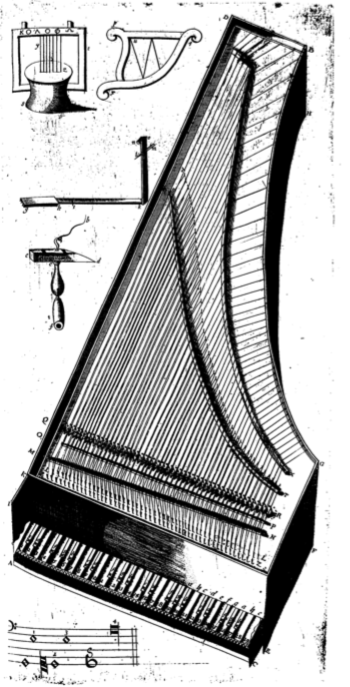

The references to the Clavecin are rare during the sixteenth century, even into the first decades of the seventeenth century. The most important keyboard instruments on that time in France were imported from Italy or Flanders. During the early seventeenth century the spinet started to decline in social prestige, and apart from an amateur domestic use, its serious practitioners appear to have been a relatively small number of professionals, mainly organists. There was no clear distinction between the repertoires of the harpsichord (spinets) and organs during the early part of the seventeenth century, or in the century before.

The pieces published in 1670 were an anthology chosen from the composer’s life work and gathered into groups or suites, defined by the key.

In his pieces, there are examples of the most fashionable dances at that time (Allemandes, Sarabandes, Gigues, Pavanes, Chaconnes…) but in his production, the Courantes stand out in number and in quality. We can find in his music more than seventy Courantes. He uses the normal order for the dances in this period, consist of an Allemande, two or three Courantes and a Sarabande, to which a final piece is sometimes added.

The Courantes by Chambonnières are following the classic model of this musical form, showing a clear ambiguity in the phrasing and in the rhythm and an alternation between the 3 / 2 and the 6 / 4. As is usual in this dance the first part is always shorter than the second one.

He does not use the alternative movement, typical of the lute Courante, in which melody and bass move in parallel thirds or tenths.

As with lute Courantes, some of Chambonnieres's have petites reprises either fully written out or marked with a renvoi.

“Chambonnieres's basses share the irregular scalic structure of the lute Courantes. Chambonnieres is conservative in his use of the melodic type of Courante, in the use of the repeated chords in the cadence patterns and in the melodic structures. A strain typically consists of a characteristic opening figure, establishing the allure of the dance, followed by a series of asymmetrical but balanced patterns of increasing length (typically of 3 - 4 - 7 bars). Some Courantes have a very symmetrical phrase construction. Imitation, where it is used, is most commonly direct, but it may also be inverted or augmented. Doubles are constructed mainly from quaver decoration of the melodic line”.

- Louis Couperin (c. 1626 - 1661):

Most of the information about Louis's life can be found in the work “Le Parnasse François”, written by Évrard Titon du Tillet (1677 - 1762) in 1732, which is a very valuable source of information to know the biographical and professional career of the main poets and musicians of France during the Reign of Louis XIV. We also find important facts about Louis Couperin's life in the “Lettre de Mr. Le Gallois a Mademoiselle Regnault de Solier touchant la Musique”, written by Jean Gallois (1632 - 1707) in 1680. He started his musical studies with his father. Louis was a great keyboard and viola da gamba performer, as well as a composer, when around 1650, according to Titon du Tillet, he visited Chambonnières, who was travelling through the region of Brie. After a small demonstration of Louis’s musical compositions, Chambonnières was impressed with him and insisted on taking charge of Louis's musical training in Paris, thus introducing him into the musical world of Louis XIV's court. With the arrival of Louis Couperin in Paris, he came into contact with some of the leading musicians of the time, like d’Anglebert, Lebègue, Blancrocher and Froberger. In 1653, Louis Couperin became the organist of the Saint Gervais church in Paris, one of the most important and best paid positions in France at the time. Louis Couperin also entered the service of the court as a viola da gamba player and, according to Titon du Tillet, he rejected the offer to work as Ordinaire de la chambre du Roy pour le clavecin, since this post was occupied by his friend Chambonnières. During his last years, he was also working for the diplomat Abel Servien (1593 - 1659) in Meudon, as organist and harpsichordist.

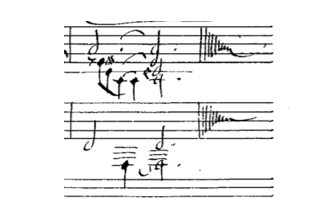

Louis Couperin wrote almost his entire oeuvre for harpsichord, but he also wrote few pieces for organ and for ensemble. His production for harpsichord is formed by fourteen “Preludes non Mesurés” and more than one hundred dances. The music composed by Louis Couperin was profoundly influenced by Chambonnières and by Froberger.

As in Chambonnière’s music, we can see all the common dances in Louis Couperin’s music, finding more than thirty Courantes. These dances are following the models of his master Chambonnières, but in the case of Couperin, the dances are longer and with some more elements of counterpoint.

“In structure, the Courantes of Louis Couperin are similar to those of Chambonnieres. Couperin’s tenor often imitates the melodic line, even if the imitation is frequently not exact. These Courantes, are more lively rhythmically than the examples of Chambonnieres. His Courantes keep close to the standard three part format, although some have much four-part writing. Cadence formulas may have a slightly more style brisé form than in Chambonnieres”.

“In general, there is little in d’Anglebert’s Courantes to recall, these Courantes employ the common formal and textural principles of the keyboard tradition. The prominence of the melodic line is expressed in his very profuse ornamentation, fully notated or indicated with signs. The melodic decoration (that contributes to the rich texture), the rhythmic solidity and the full texture, are the most important are characteristics of d’Anglebert's style. We can find fewer elements of lute style than in Louis Couperin’s examples”.

One important characteristic of d’Anglebert style is that he tends to fill out broken chords with acciaccaturas, as he explains in his treatise “Principes de l’Accompagnement”.

There are two main sources for the Jean-Henry d’Anglebert’s harpsichord music, the “Pieces de Clavecin” (1689) and the Manuscript Rés 89 ter. We can find also pieces by d’Anglebert in the Bauyn Manuscript and in the Parville Manuscript. In all these sources there are, at least, ten Courantes.

Resume:

After the study and analysis of this music, we can obtain some conclusions for making a resume about the Courante Françoise in harpsichord repertoire. As we know, the Courante is the slowest (Grave) dance of the seventeenth century French Suite and we can find some common elements in all these pieces:

- Time signature 3 shows us the 3 / 2 bar, with three slow beats per bar.

- The tempo in the Courantes for harpsichord could be slightly faster than in other examples (lute, viola de gamba and ensemble pieces).

- Ornamentation, principally in the melody line, should follow a vocal way, full and varied.

- Bass lines should provide the harmonic foundation of the movement.

- Courantes can be played with great freedom, but the tempo has to be stable.

- As a general rule, the “Inegal notes” are quite unsuitable on these dances. But the Inegal can be appreciated through the Iamb and triple Dactyl feet.

- Flexibility or ambiguity that “Proportio Sesquialtera” can offer. The juxtaposition between the meter 3 / 2 and the 6 / 4 can be explored by the performer.

- Use of petites reprises, that were useful in danced Courantes to create the pair number of bars.

- Continuous melody lines and broken texture (style brisé) in the accompaniment.

- Passing modulations and retarded cadences are typical elements of these dances.

Even through some different aesthetic elements in the Courantes of each composer, it is clear that the style is fundamentally the same and we can analyze the Courantes from the second half of the seventeenth century as a unit.

4.3. Correntes and Courantes in Harpsichord music:

Some of the firsts important examples of Correntes are in early sources as “The Fitzwilliam Virginal Book”, “Il secondo libro di toccate, canzone, versi d’himni, Magnificat, gagliarde, correnti et altre partite” by Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583 - 1643) and “Terpsichore” by Michael Preatorius (1571 - 1621). In the second half of the seventeenth century Italian composers, as Michelangelo Rossi (c.1601 - 1656), Bernardo Pasquini (1637 - 1710), Bernardo Storace (c. 1637 - 1707) continued composing Correntes.

There are a lot of examples of French Courantes in harpsichord Suites and collections by:

- Jacques Champion de Chambonnières (c. 1601 - 1672)

- Louis Couperin (c. 1626 - 1661)

- Jean - Henry d’Anglebert (1629 - 1691)

- Jacques Hardel (c. 1643 - 1678)

- Étienne Richard (c. 1621 - 1669)

- Henri Dumont (1610 - 1684)

- Nicholas - Antoine Lebègue (c. 1631 - 1702)

- Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre (1665 - 1729)

- Louis Marchand (1669 - 1732)

But examples of French Courantes are not only found in French sources. German keyboard composers also adopt this dance in their music, Composers as:

- Johann Jakob Froberger (1616 - 1667)

- Johann Adam Reincken (1643 - 1722)

- Johann Pachelbel (1653 - 1706)

- Dietrich Buxtehude (1637 - 1707)

- Johann Kuhnau (1660 - 1722)

The Courantes by François Couperin (1668 - 1733) and Jean - Philippe Rameau (1683 - 1764) take this form to the extreme with great harmonic tension and very developed ornamentation. During this period the Courante was already decaying in popularity.

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685 - 1750) distinguished in his Suites between Corrente and Courante, so there are examples of Correntes in the First, Third, Fifth and Sixth “Partitas” for harpsichord, in the Second, Fourth, Fifth and Sixth “French Suites”. These movements are written in 3 / 4 or 3 / 8 with a simple texture, clear harmonic and rhythmic movement and a virtuosic figuration in the upper voice. The examples of French Courantes in Johann Sebastian Bach’s music are found in all the “English Suites”, in the First and Third “French Suites” and also in the Second and Fourth “Partitas” for harpsichord, among others. These Courantes by Bach are less ambiguous rhythmically than the French examples.

From the second half of the seventeenth century, the harpsichord appears as a favourite instrument of the aristocracy and the richer bourgeoisie, equal to the lute. From the written by Mersenne, it is clear that the new style developed by Chambonnières was associated with the harpsichord rather than the spinet, with a greater capacity for resonance and a more brilliant sound.

Spinet and harpsichord were used in the earlier seventeenth century to accompany voices, sometimes in combination with lute and theorbo, but more significant for the development of keyboard repertoire is their association with the viol consort, it seems that keyboard instruments appear to have been an indispensable part of the viol consort. “If the harpsichord was capable of doubling the parts of a consort then it was capable of playing them alone, and indeed a number of viol publications appeared throughout the century with a keyboard performance option”. This transfer of repertoire was not limited to polyphonic music and also included dance movements. Recent research highlights that keyboard arrangements, mostly of Lully's orchestral music, formed a major part of the keyboard repertory during the seventeenth century, and were as important as original pieces in shaping the development of this new keyboard style.

The idea that purely instrumental music during the sixteenth and earlier seventeenth century was written in tablature give us the idea that the harpsichordists during that period were able to read from any tablature, also that one for lute, which makes the transfer of repertoire from one instrument to other easier.

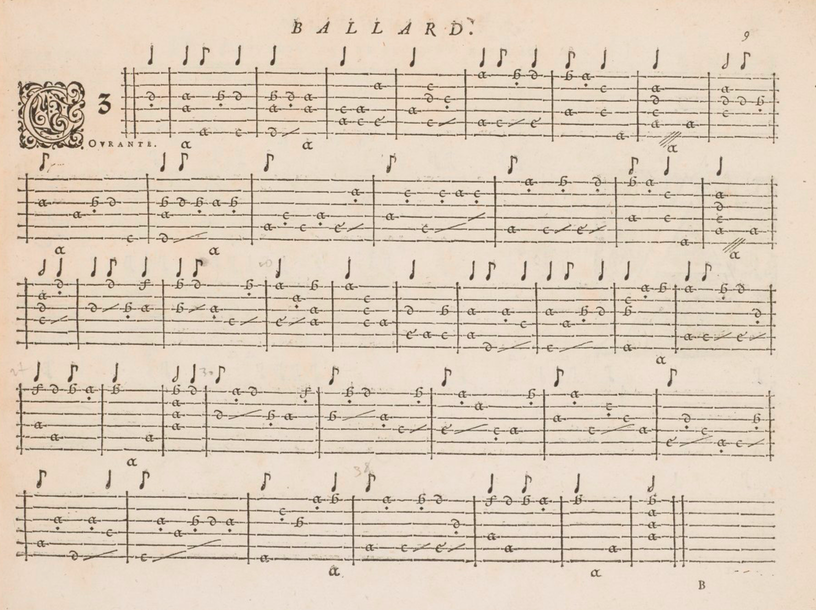

Dance genres were important in both the lute and harpsichord traditions. Until the sixteenth century, dance Suites were not composed in a standard order but were rather set in binary form or grouped in contrasting forms, which was characteristic for the lute style (style brisé). Two lute anthologies published by Ballard in the first half of the seventeenth century were the first to show the standard Suite organization of Preludes, Allemandes, Courantes, and Sarabandes. The organization of Suites by diatonic keys, instead of modes, was an innovation of the lutenist Denis Gaultier.

In France, from the second half of the seventeenth century, the music for organ was totally separated from the music for string keyboard instruments. The differences between the organ and the harpsichord music can be appreciated in the musical forms, in the principal composers and in the places, as we can see the table below:

|

ORGAN |

HARPSICHORD |

|

|

Musical Forms |

Polyphonic works and Pieces for the church services. |

Dances. |

|

Places |

Big French Cathedrals and Churches. |

The Court in Paris and Versailles. |

|

Principal Composers |

Jean Titelouze, François Roberday, Nicolas Gigault, Guillaume-Gabriel Nivers. |

Jacques Champion de Chambonnières, Louis Couperin and Jean-Henry d’Anglebert. |

To have a complete vision of the Courante for harpsichord during the second half of the seventeenth century in France, this research is focused on the three main composers:

- Jacques Champion de Chambonnières.

- Louis Couperin.

- Jean-Henry d’Anglebert.Jacques

- Champion de Chambonnières (c. 1601 - 1672):

Little information is known about Chambonnière’s early education and personal life. From 1632 he appears as Gentilhomme de la Chambre du Roy, a job that his father had already occupied. After Louis XIII’s death, he continued working at the Court. But when Louis XIV chose Etienne Richard as his harpsichord teacher, Chambonnière’s career in the court was less and less important until 1662, when d’Anglebert obtained the title, Ordinaire de la chambre du Roy pour le clavecin. Despite, he continued working as an instrumentalist in the Court until his death.

We know more than one hundred and forty pieces for harpsichord by Jacques Champion de Chambonnières, and all of them are dances. In 1670 Chambonnières published the two books of “Pieces de Clavessin”, with sixty pieces. The other pieces are contained in different manuscripts, principally in the Bauyn Manuscript, in the Manuscript Rés 89 ter, in the Manuscript 2356 and in the Manuscripts 2348 and 2353.

There are two principal sources for the Louis Couperin’s harpsichord music, the Bauyn Manuscript and the Parville Manuscript.

- Jean-Henry d’Anglebert (1629 - 1691):

D’Anglebert largely escaped the attention of contemporary music writers as Jean le Gallois and Titon du Tillet (unlike Louis Couperin and Chambonnières). Even Michel de Saint Lambert makes reference to d’Anglebert strictly in the context of the published book “Pieces de Clavecin”. This means that we know very little about d’Anglebert’s life and his formation. He started his career in Paris as organist at the Jacobin church in the Rue Saint-Honoré and working as a harpsichordist at the Court. From 1660 he obtained the position as a harpsichord player for the Duke of Orléans, Louis XIV’s brother, and from 1662 he is the working as Ordinaire de la musique de la chambre du roy pour le clavecin.

“Pieces de Clavecin” was published in 1689, two years before the composer’s death, and this volume resumes d’Anglebert’s achievements as a composer, harpsichordist and teacher.

D’Anglebert provides in the Manuscript Rés 89 ter. doubles for some of the Chambonnière’s Courantes.

The Courantes are by far the largest group of dances in the d’Anglebert's lute arrangements from the Manuscript Rés 89 ter. All of these dances are attributed to Ennemond Gautier.

In d’Anglebert’s Courantes, the right hand reflects the lute melody lines with occasional chords for accentual purposes and the lute's ambiguity of melody and alto part, but the left hand is generally worked in the brise style with two parts of the standard keyboard format.

3. THE FRENCH COURANTE: IN THE SEARCH OF ITS ORIGIN

3.1. MUSICAL FORM COURANTE: HISTORICAL ANALYSIS

- The musical background: before and after the classic “Suite de Danses”:

The origin and characteristics of the dances called Courante seems too broad, general and not always specific. The multiple versions of the name from the French Courir or from the Italian Correre (to run), suggest a succession of running notes. Nevertheless, after being submerged in the numerous amount of musical examples, I dare to say that this description or reference is not enough and it causes confusion especially to kind of Courante treated in this work. Nevertheless, the definition of this dance as a succession of running notes shows us some important information. Following the previous examples found in the Suites de Branles, the Courante is a constant dance, that is, this form is continuous and the combination of the step sequences is not interrupted. This characteristic is one of the main differences with the other French court dances.

There are several names for this dance and instrumental form, the term Courante was used in France and Flanders, Corrente in Italy and Spain and Corant in England. But we can find in different sources around Europe names as Courrante, Coranto, Corranto, Currendo, among others.

I. I. Antecedents: Branles and Basse Danses:

Before the development of the Courante Françoise, during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the Bassedanses and the Branles were the most popular dances in Europe. There are some clear connections between these dances and the later Courantes:

- Bassedanses has the same time signature, has also the flowing or running character in the music and the dance remain majestic as the Courante.

- Branles, especially at the beginning of the seventeenth century, were similar in the musical structure to the French Courante and their specific “Suite” were the preamble to the Suite of (French) Courantes (as in Cassel’s Manuscript). The Branle Simple is one of the few examples of early dances in triple meter.

The Bassandanse was the principal Court dance during the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance. The name of this dance was first cited in the poem “Quar mot ome fan vers” by the Occitan troubadour Raimond de Cornethere in 1340, but the earlier documents known describing steps and music are from the fifteenth century. The character of the dance is implicit in the name, which announced a dance close to the ground, generally lacking the rapid movements and leaps characteristic of the Alta Dansa or Saltarello. The combination of these two types to form a varied pair can be documented throughout Europe from the late Middle Ages. As a general rule, the Bassadanses have been performed in a triple metre (6 / 4 or 3 / 2), but the choreographies are in duple meter, creating sometimes the effect of “hemiola” or “proportio sesquialtera”.

“Sesquialtera” (one whole plus its half) was the most commonly used of all rhythmical proportions and it means that three notes are introduced in the time of two of the same duration, there is a change from duple to triple time but the tactus is constant. It was frequently indicated only by the signature 3, and took over the name tripla. Some examples of dances, as some French Courantes, are notated with the time signature 2 / 3 to denote the sesquialtera proportion.

The terms “hemiola” and “sesquialtera” both signify the ratio 3 : 2, and in music were first used to describe relations of pitch (the justly tuned pitch ratio of a perfect fifth means that the upper note makes three vibrations in the same amount of time that the lower note makes two).

Although the “hemiola” resembled “sesquialtera”, in effect (three in the time of two) the term “hemiola” is used to refer to the momentary intrusion of a group of three duple notes in the time of two triple notes, and was notated by coloration (three red notes for two black ones, three black notes for two white ones, etc.). From the fifteenth century, both terms were used to describe rhythmic relationships, specifically the coloration. In resume, the “hemiola” properly applies to a momentary occurrence of three duple values in place of two triple ones, and “sesquialtera” represents a proportional metric change between successive sections. In the Courantes the superposition of two against three is very common.

The dances mainly called Branle, are meant to be danced in a group. There were extremely popular during the sixteenth century since there are many musical examples with different names referring to the steps, places or even professions. Illustrations of the dance go back to medieval times, but the term branle is rarely encountered before the sixteenth century (except as a designation for one of the steps of the bassedanse). In the treatise “Ad suos compagnones”, written around 1519 by Antonius de Arena have described three kinds of branles: double, simple and coupé. Thoinot Arbeau (1519 - 1595) in his “Orchesographie” mentioned four types of branle: double, simple, gay and Burgundian. The typical suite of branles around 1600 added four more dances to the types of Arbeau: the branle de Poitou, the branle double de Poitou, the branle Montirandé and the gavotte.

It is important to highlight that the Courante is first, during the sixteenth century, musically linked to other dances, such as Bransle Courant, Allemande Courant or Courant Sarabande. Arbeau's “Branle de la Haye” is explained to be danced en façon de courante. This means, that the step patterns are the same as those given for the Courante. Fiona Garlick's dissertation “The Measure of Decorum. Social Order and Dance Suite in the Reign of Louis XIV” points out the possibility that the Courante might originally have been a type of Branle.

We find the first musical examples of Courantes during the sixteenth century in the collection of dances published by Pierre Phalèse in Leuven and Antwerp. In this collection, we find Flemish music by Sebastian Vredeman (c. 1540 - c. 1600) or Emanuel Adriaenssen (c. 1554 - 1604) and the Courante appeared as an isolated dance.

Not only Bassedanses and Branles were related to the Courante on the sixteenth century, but the ostinato bass “La Romanesca” has also a very important connection with the early Courante. The two Balletti based on this bass found in Fabritio Caroso's “Il Ballarino” are related, apart from the clear “proportio sesquialtera”, to the later Courante in some details:

- Gratia d’Amore: Is a couple dance, written as a Balletto (suite in two parts) and with a clear representative and theatrical character. The first part is stately, with a ceremonial character (as the Courante), in duple meter and the second part (Sciolta) is lively and festive, organized in triple meter. This Balleto is dedicated to Beatrice Orsina Sforza Conti, who married in 1571 Federico II Sforza Conti of Valmontone and became a widow in the same year of the publication of “Il Ballarino”.

- Chiaranzana: Is a ballroom, social dance, for as many couples as you wish in form of a suite with two parts (the first part in duple meter and the second part in triple meter). The number of couples determines the duration of the first part, and this fact is related to the Suite of Branles and the later Suite of Courantes.

The tempo for the dances based on the ostinato bass “La Romanesca”, as in the later Courantes, is determined by the running notes, as in for example in “Recercada Settima” by Diego Ortiz, where the tempo is marked for the part with the diminutions. If the tempo is too slow, the diminutions and the tempo won’t be understood and if the tempo is too fast, the diminutions will seem a caricature or a joke.

I. II. From the Renaissance Courante to “La Bocanne”:

Patata, pototum, sed fit corrensia gaya

et de brim & de broc intravagando pedes.

Est mihi difficiles multum passagius iste,

Istam correndam nemo docere potest.

Intendio melius quam vobis dicere possim,

Usus vos tantum scire docebit eam.

This is the first notice about the Courante found in the treatise “Ad suos compagnones” by Antonius de Arena, when it was still a brand new dance in the early sixteenth century. Although no concrete movement can be reconstructed from this text passage one still has an impression of a lively dance with evidently somewhat complicated steps, which is consistent with the derivation of his name (to run).

Originally the Courante has not been part of the Suite de Danses from its origin. In the beginning, it was an isolated dance (as in the examples provided by Pierre Phalèse, Thoinot Arbeau and Cesare Negri). On the seventeenth century it happened the proliferation of the composition of this type of dance around Europe, either as Courante or Corrente, and either isolated, in groups / Suites (as in the examples by Praetorius) or coupled with a previous slow dance (first with the Pavane or later with the Allemande).

Until the first decades of the seventeenth century, the Courante was a dance with two sections in triple meter (usually 6 / 4), but the phrasing was still binary (following the old fashion as in the examples by Arbeau). There must be a sort of mutation that turns the same dance into a ternary dance.

The most important information about the early Courante can be deduced analyzing the examples found in “Terpsichore” by Michael Preatorius and in the different manuscripts from the “Philidor collection”, both sources for different settings of instruments.

On the other hand, very little information can be obtained about the Courante from the few early seventeenth century keyboard sources (music by Jacques Cellier (? - c. 1620), Guillaume Costeley (c. 1530 - 1606) and Pierre Megnier (? - ?) in the two “Cellier’s Manuscripts”). The common feature of all these examples is that they attempt to adopt for the harpsichord music the innovations of the lute style.

Michael Praetorius (1571 - 1621) planned a series of secular music named after the Greek muses, but finally, he only managed to publish only one of these collections called “Terpsichore, musarum aoniarum quinta”. This collection contains more than three hundred French dances in four, five and six parts.

Praetorius’s versions of French dances are his own arrangements, based on melodies and bass lines provided by Antoine Emeraud (French dancing master in the Court in Brunswick) and Pierre Francisque Caroubel (French violin player who worked in the Vingt-quatre violins du roy). Praetorius arrangements seem to be used for concert performances or for social dancing.

“Terpsichore” is organized by musical forms starting the treatise with suites of Branles, followed by suites of Courantes, and then Voltes, Ballets and Passamezzos and Galliards. We can find in “Terpsichore”, as Praetorius marks on the front page, one hundred and sixty two Courantes.

Praetorius in the first part of the third book of his treatise “Syntagma Musicum” is focused on the musical forms, including a brief description of the Courante. Praetorius sets the Courante with the Branle, Volta, Allemande and Mascherada, as compositions without text and dances without regard to certain dance steps. He defines this dance as:

“Courantes get their name from Currendo or Cursitando because there are

generally certain measured up and down skips,

similar to running while dancing”.

Marin Mersenne (1588 - 1648) in “Traité de l'Harmonie Universelle” talks about the Courante in the Part I of this treatise, in a chapter called “Traitéz de la voix et des chants, Live II: Des chants”. Mersenne says about the Courante that is the most common dance in France on that period and is only danced by two persons at the same time. He also introduces the concepts of the metrical feet “Iamb” (short and long) and the “Proportio Sesquialtera” in the context of this dance. Mersenne says about this dance:

“The movement is called sesquialtera or triple”.

Mersenne provides some musical examples and the important reference to the relation between the dance called “La Vignonne” and the Courante “La Bocanne”. This reference is very important because this change could be the point for the transition between the Renaissance Courante (in duple meter: “La Vignonne”) and the traditional French Courante (in triple meter: “La Bocanne”). The Courante “La Bocanne” was probably composed at the beginning of the seventeenth century. Marin Mersenne mentioned the Courante “La Bocane” in his treatise “Harmonie Universelle”:

“La Bocanne is a figured courante, with its own particular step-patterns and

figures; it has four couplets, that is to say the air has a first strain played twice

and a second strain played twice: it was previously called La Vignonne but a

new air has been composed and it has taken the name of its author…”

The first official appearance of the Courante “La Vignonne” was in the lutenist Robert Ballard’s publication “Diverses piesces mises sur le luth par R. Ballard”, published in Paris in 1614 by Pierre Ballard. Mersenne doesn’t say about “La Vignonne” that is a Courante, but we can understand it because this dance was a very popular tune around Europe during the seventeenth century and because in the previous publications as in Ballard or Vallet’s books, “La Vignonne” appears in the section dedicated to the Courantes. The origin of this dance is not clear yet, but there are some possibilities, Mersenne did not mention that “La Vignonne” was called like that by the name of its composer, but if we follow this line of investigation we will find a musician called Jérôme Vignon working for the Duke of Lorraine in 1631. Since the dates do not seem to match, it is difficult to believe in this theory, even more, if we observe the “Courante CXLVII á 4” by Michael Praetorius as “Incerti” (anonymous) or the “Courante CXVII á 4” signed as “M.P.C.” published in “Terpsichore” (1612). These Courantes are similar dances as “La Vignonne”, with parallel melody lines, with an upbeat, with a faster motif in the final part of the second part and with the same number of bars (divided in a different way: eight bars in the first part and ten bars in the second part).

The Courantes found in “Terpsichore” shows us that possibly the origin of this dance is even earlier because it was popular before 1612, the year in which Praetorius published his book in Wolfenbüttel (Germany).

There is no existent choreography for “La Vignonne”, but if we apply the usual step sequence for the Renaissance Courantes (in duple meter), explained by Thoinot Arbeau in his treatise “Orchesographie”, adding a bow or Reverence, at the beginning or at the final of each section, as François de Lauze says, we will find a possible choreography for the nine bars phrases found in “La Vignonne”. It could be also possible to apply the steps obtained from Arbeau’s “Branle de La Haye”, that are basically only the second part of the step sequence for the Renaissance Courantes, that could fit better in a triple meter.

“La Vignonne” and “La Bocanne” has the same general structure with two nine bar sections repeated twice, with the melody line with some coincidences, with a clear upbeat (not very common until the development of the dance music during seventeenth century) and with the long notes in the second half (as a fermatas, showing a clear theatrical character). The issue that now we have to resolve is to find how the dance “La Vignonne” in duple meter (as the Renaissance Courantes) mutate to the triple meter in “La Bocanne”.

The Courante Françoise, as we said before, suffered significant changes during the first decades of the seventeenth century, and these took place at the time of the style change from the Renaissance to Baroque style in music and dance. The problem we have is that this highly interesting period in musical history is only sparsely documented, there are no dance treatises containing choreographies from the firsts two decades of the seventeenth century, so we don’t even know if this change of style happened gradually or if it occurred at the same time in Italy and France. The first mutation has relation with the evolution of taste, and the change from the renaissance aesthetic to the baroque aesthetic altered totally the characteristics of this dance, and a more simple and lively dance is upgraded in favour of a more complex polyphonic composition with a richer harmony and ornamentation.

The second mutation, probably the most important change, which affects the music and the dance, takes place in the rhythmic grouping within a six-measure. The six strokes of the bar, which previously formed two groups of three (duple meter), are now forming three groups two (triple meter): so the basic schema of the French Courante mutates from | 1 2 3 - 1 2 3 | or | 1 2 3 - 1 2 3 | to | 1 2 - 1 2 - 1 2 |.

Pamela Jones in her dissertation points out that the steps and music in late renaissance choreographies are subject to alteration of rhythm throughout perfection, imperfection, and other mensural devices. It is important to highlight that note values on that time represent only relative durations, so the proportions between the note values of the music and the steps in the choreography are not always the same. In late renaissance dance any step may appear in any dance, so steps described in duple meter often appear in triple meter dances and vice versa. In the period around 1600, a new kind of rhythm notation prevailed, in which the note values no longer had to be interpreted out of context as before (as in mensural notation), but were clearly fixed. Arbeau and Negri's dances usually use this modern way of notation, but in some cases, both old and new notation are used in the same dance, leading to apparent changes of measure and confusion. For example, in Caroso’s second treatise, he adds specific musical time values in the step descriptions, but he is still using the old terminology for the steps.

So, if we apply this change in the division of the smaller note values (prolatio), into the Courantes in duple meter, then there would be a six beats bar, that can be divided into duple or triple subdivisions.

Coloration in a more general sense, full notes used in opposition to void notes for rhythmic purposes, survived in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries especially for expressing “hemiola” rhythms in 3 / 2 time, three full semibreves or equivalent replacing two normal voids dotted semibreves. But soon after 1600, coloration was used for entire movements in mensural notation, such as Courantes, whether or not “hemiola” rhythms were intended.

From the beginning of the seventeenth century, the measures formed by six beats can be divided into three groups of two notes or in two groups of three notes. Now the dance can explain the rhythmical ambiguity of the Courantes and why the subdivision in triple meter was the preferred during the next decades.

In most dance types one step unit equals one measure of music, but the Courante is unique in having one and a half units per measure. Raoul August Feuillet explains this structure:

“It is to be observ'd nevertheless, that in Courant Movements, two Steps are put to each

Barr or Measure; the first of which [a whole unit] takes up two parts in three of the

Measure, and the second [a half unit] takes up the third part.”

The whole unit of two steps plus the one step of the half unit are equal to the three minims which comprise a measure of Courante, and these rhythmic stresses divide the typical measure of the Courantes in | 1 2 - 3 4 - 1 2 |.

Some variations are found in the rhythm and in the dance of the Courantes showing the characteristic rhythmical ambiguities of these dances:

- Occasionally a half unit is placed first: | 1 2 - 1 2 - 3 4 |.

- An equal division: | 1 2 3 - 1 2 3 | or | 1 2 - 1 2 - 1 2 |.

Finally, all these different combinations can be explained through some metrical proportions. As Sir John Davies says in his poem “Orchestra” from 1596, the division in the Courantes is governed by the “triple dactyl” foot. The second half of this metrical foot has the value of an “iamb”. Mersenne says that the air of a Courante is measured by the “iambic” foot; and the combinations between the “triple dactyl” foot, the “iambic” foot and the sesquialtera proportion makes all the possible rhythmic patterns in Courantes.

The beat becomes ambiguous in these dances: within the same piece of music, one grouping can apply once, and the other one. And finally, this ambiguity becomes the stylistic device of the composition of the Courantes during the seventeenth century.

Derived from all these changes an increasingly slower tempo is fixed for the seventeenth century French Courantes.

It is not possible to offer a final answer about why this change happened in the Courantes, neither is the intention of this research, but all these reasons could explain it, at least, partially.

Some of the earliest examples of Courantes are found in lute music by composers as Julien Perrichon (1566 - c. 1600), Robert Ballard (c. 1572 - 1650), Nicolas Vallet (c. 1583 - c. 1642) or Ennemond Gaultier (c. 1575 - 1651). These pieces, like the early Italian and English dances, have a regular phrasing and a simple texture, but we can start finding a new interest for the counterpoint, an extended use of the ornamentation and a more rhythmic tension. These sources are coming from the lute repertoire not only because of its popularity but its convenience of the notation in tablature, specially invented for instrumental music. These earlier examples are the beginning for a new development of this dance, but are not yet in triple meter, as in the later examples, so the Courante is still in a transition period between the Renaissance type and the typically French Courante. We can find in these Courantes an important rhythmical ambiguity between duple and triple meter.

I. III. Suite de Danses, Courante VS Corrente:

The first form of the primitive Suite was a slow dance followed by a quick one. In the sixteenth century, the Pavane and the Gaillarde (both derived from the Bassedanse) were used to replace more primitive pairs of dances. The Gaillarde experimented a similar change, as the Courante, in England and in France at the beginning of the seventeenth century, changing the 6 / 4 in a duple meter to the 6 / 4 in a triple meter. Especially in France the Gaillarde fell into disuse (it represents an old fashioned name from the previous century) and the Courante became popular with some similar characteristics.

Allemande and Courante were then added to build the Suite of the early seventeenth century. During this century the Sarabande was attached, and then, when the Gigue was added, the Pavane and Gaillarde fell into disuse, leaving the Allemande, Courante, Sarabande and Gigue as the basic structure of the set. We may take it that the Courante formed the connecting link between the early Basse Danse, Branle and Gaillarde and the later Cannaries and Gigues on the one hand, and led to the Menuet.

From the second half of the seventeenth century we can difference totally the two different types of dance: the Italian Corrente and the French Courante. At this time the Courante, either French or Italian, became more of an instrumental composition and less to be danced, maintaining some dance elements but also losing some others.

It is important to say that the enormous amount of compositions during the seventeenth century is because the Courante was extremely fashionable around Europe, not only as a dance but also as an instrumental genre.

Also is important to remark that dance music, except for some examples like “Terpsichore”, remained exclusively to be danced, but not only socially because on this time, during the reign of Louis XIII, also appeared the ballet at the theatre and at the opera dedicated for professional dancers. The Courante is out of this context because it was already an old dance.And it is only used just to remember how it was at the beginning of the past century, as for example André Campra (1660 - 1744) in 1699 at the end of his opera “Le Carnaval de Venise” composed a grand ball with a Courante after the suite of branles (branle, branle gay, branle à mener and gavotte).

The Italian Corrente is usually in 3 / 4 or in 3 / 8 with a clear harmonic and rhythmic structure. The first examples of Correntes were written with a free texture, and sometimes includes imitations.

The Italian Corrente was very popular around Europe during the firsts decades of the seventeenth century. In Germany, there are some remarkable examples in “Tabulatura Nova” by Samuel Scheidt (1587 - 1654) and in “Banchetto Musicale” by Johann Hermann Schein (1586 - 1630). This type of Corrente was of the dance in duple compound rhythm or time signature 6 / 4. Also, it has mostly a binary rhythm or the musical phrase is in two. Actually, in this type, there is no clear difference between the French or Italian denomination. The same characteristics are found in English sources.

This dance with their own characteristics continued their evolution and during the second half of the seventeenth century, composers as Arcangello Corelli (1653 - 1713) were writing Correntes following this old style. The composers from that time prefer a more simple Corrente with a clear homophonic texture and a virtuosic figuration in the upper voices.

In the eighteenth century the Corrente form was used by composers as Johann Sebastian Bach (1685 - 1750) in his orchestral (First Orchestral Suite), chamber and solo music (First, Second, Third, Fourth and Sixth Suites for cello, Partita for flute and First and Second Partitas for violin) or Georg Friedrich Handel (1685 - 1759) in his Suites for harpsichord and in some operas. Handel used the term Courante after the Allemandes, but these movements are usually quite similar to the Italian Correntes, all in 3 / 4 with a binary form and a simple texture.

- The appearance and evolution of the Courante Françoise:

The Courante Françoise is clearly a genre that came out the dance.

French Courante is usually in 3 / 2 or 6 / 4, with a character Grave and characterized by rhythmic and metrical ambiguities. It is quite common the alternation and juxtaposition between the two meters, called “Proportio Sesquialtera”. The Courante always starts with an upbeat, and this is very important because it could be the origin of the upbeat in dance music. The Courante generally is consisted of two sections, with around eight bars each part repeated.

The Courante is the French dance in three with the slowest tempo. Some Courantes are faster than others “…according to evidence from several early eighteen-century French composers. François Couperin, in “Les Nations”, contains pieces marked as follows: Premier Courante, Noblement and Seconde Courante, un peu plus viste… and Nicholas - Antoine Lebégue wrote a Courante grave followed by a Courante gaye, both in French style”. We can appreciate that the second Courante is always faster than the first one, and these second Courantes could be a reminiscence of the many suites de Courantes (as in Cassel’s Manuscript).

The Courante became one of the most popular dances from the second third of the seventeenth century in instrumental music, especially in harpsichord examples. These Courantes have the very characteristic rhythmical and metrical fluidity, a complex texture, a great harmonic tension and a very developed ornamentation.

From the eighteenth century, the publications and treatises that treat the topic of the Courante are increasing and we can highlight some of them:

Charles Masson (? - ?) in the first chapter of his treatise “Nouveau traité des regles pour le composition de la musique”, called “De la musique”, there is a small subchapter with the name “De la mesure et de la difference de ses mouvements”. In this subchapter Masson divides the dances depending on the beats per bar, in two, in three and in four. The dances in three have another division: Grave (Sarabande, Passacaille and Courante) and Legerement (Chaconne, Menuet and Passepied). One of the most important things in Masson’s treatise is that he refers to real examples of music by Jean Baptiste Lully.

Jean-Pierre Freillon Poncein (? - ?) wrote “La veritable maniere d'apprendre a jouer en perfection du haut-bois, de la flute et du flageolet”. The information in this treatise is quite simple but he talks about some important characteristics. Freillon Poncein says “we start with the last eight note of the measure, which is marked by a 2 / 3”. He explains that the usual number of bars for the first part of a Courante are five, six or seven, and for the second part are the same or one bar more than in the first part, explaining also that the most common combination is six bars in each part.

Sébastien de Brossard (1655 - 1730) published his “Dictionnaire de Musique” in Paris in 1701. Following the English translation made by James Grassineau (1715 - 1769), published in London in 1740, the term Courante is described as:

“Is used to express the air or tune, and the dance to it. With regard to the first, Courant

or Currant is a piece of musical composition in triple time, and is ordinarily

noted in triples of minims, the parts to be repeated twice. It begins and ends

when he who beats the measure falls his hand with a small note before the beat;

in contradiction from the Saraband, which usually ends when the hand is raised”.

Pierre Dupont (? - ?) describes the different time signatures in “Principes de musique par demande et par réponse par lequel toutes personnes pourront apprendre d'eux-même a connoître toute la musique”. Explaining the time signature 3 / 2, he says that the Courante is the most grave dance and the notes should be played detaché.

Johann Gottfried Walther (1684 - 1748) published the first dictionary of music in the German language, “Musicalisches Lexicon”. Walther explains musical terms but he also offers biographical information about composers and performers. He says about the Courante that is a dance in two parts with repeats, written in 3 / 4 or 3 / 2, and he is speaking about the “Proportio Sesquialtera”. For Walther the rhythm of the Courante is “absolutely the most serious one can find”.

Walther quotes some works written by Mattheson.

“Der Vollkommene Capellmeister” written by Johannes Mattheson (1681 - 1764) is one of the biggest theoretical works about music in the Baroque period. It is a compendium about the musical taste, the musical theory and the performance practice in his time. This large volume is a fundamental work for understanding the music of the XVIII century. “Der Vollkommene Capellmeister” show us the practical, theoretical and aesthetic knowledge which an eighteen century Capellmeister needed to master. The chapter thirteen of the second part of this large treatise is called “On the categories of Melodies and their special characteristics”. In this chapter we can find a guide of the musical forms as an index of the categories and their characteristics, explaining styles, attributes, characteristics and affects of each form. It was written for those who want to be composers. Mattheson says that this is only a single chapter, so if you want more information about the musical forms you will need a large book. He divides this chapter into two parts: Vocal Music (order of the forms: “From imperfection to perfection”) and instrumental music (because “Instrumental pieces requires vocal melodies”: affections, caesuras of the musical rhetoric, geometric and arithmetic relationships).

Mattheson divides the Courante into four categories: for dancing, for clavier or lute, for violin or for singing. But the most important thing is the meter in 3 / 2 and the affect of “sweet hopefulness”. He also provides musical examples.

Johann Joachim Quantz (1697 - 1773) wrote a treatise for playing the traverso, “Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte traversiere zu spielen”, but we can find on it a lot of information about performance practice. His principal interest is the “Principles categories of Tempo”. Dividing the duple meters in two (“tempo minore” and “alla breve”) and triple meters in others two (equivalent categories but without a name). Quantz makes a relation between tempos and heartbeat (human pulse), and for the Courantes he says that the quarter note is around 80 bpm. The affect for a Courante based on Quantz is “grave” and “majestic”. Quantz says “the quavers that follow the dotted crochets in the Courante must not be played with their literal value, but must be executed in a very short and sharp manner”. He also wrote that the string instruments should “detach the bow during the dot” of a dotted quarter note.

Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712 - 1778) explains in one of his articles about music in “The Encyclopedia” the Courante. He describes the Courante as a dance in three, with two reprises and slow tempo. He also says that is a French Dance, and it is danced always in pairs. We can find also information in “The Encyclopedia” about the steps (Pas de Courante) and about some Choreographies. Rousseau establishes a continuation between the Courante and the later Minuet.

The treatise “Klavierschule, oder Anweisung zum Klavierspielen für Lehrer und Lernende” written by Daniel Gottlob Türk (1750 - 1813) gives us an idea of how the Courante continued the evolution during the eighteenth century. For Türk a Courante (or Corrente) is a dance in 3 / 2 (or in 3 / 4) that begins with a short upbeat and consists of running figures. The tempo is not very fast, serious character and more detached than legato.

4. COURANTE IN FRENCH SEVENTEENTH CENTURY HARPSICHORD MUSIC

The Courante Françoise is the most common dance type in harpsichord music from the seventeenth century in France (there are more than one hundred ten Courantes between the dances composed by Chambonnières, Louis Couperin and d’Anglebert). In a traditional sequence of a Suite of dances, we can find two, three or even more Courantes. Not only the Courante was the most common dance in the harpsichord music, but it was also the most prevailing dance in lute music, in chamber and in orchestral music. A remarkable example is the “Manuscript of Cassel” with Suites published by Jules Écorcheville, which contains more than two hundred pieces for three, four or five voices and fifty four of them are Courantes.

The absence of musical sources of French harpsichord music in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries has encouraged a number of conjectures about the evolution of French keyboard style before Chambonnières.

4.1. The influence of the Lute repertoire in the French keyboard tradition:

During the last decades of the sixteenth century and the first half of the seventeenth century, there is a generation of composers and lutenists who prepared the way for the music of the three great masters of the harpsichord music in France in the second half of the seventeenth century. These lutenists and composers, as René Mézangeau (c. 1568 - 1638), Ennemond Gaultier (c. 1575 - 1651), Robert Ballard (c. 1572 - 1650), Nicolas Vallet (c. 1583 - c. 1642), Pierre de La Barre (1592 - 1656), Germain Pinel (c. 1600 - 1661), Étienne Richard (c. 1621 - 1667), developed their own style for the lute. All these composers wrote, mainly, dances for lute (Allemandes, Courantes and Sarabandes), and we can see on these pieces one of the origins of the French Harpsichord Suite.

The lute’s popularity in France could explain why so little keyboard music was published in France during the sixteenth century. It seems normal, that when the French harpsichordists began to develop their own writing, they would look for inspiration into the lute music, which was considered at that time, “the noblest instrument of any”. Harpsichord composers adopted lute effects directly incorporating into the technical resources of their own instrument.

The Courantes for lute of the first half of the seventeenth century frequently derive their melodic lines from dances or airs de cour, and they have the clearly defined phraseology and melodic contour of dance music. Since the Courante as a genre is present in sources throughout the period, this shift in orientation away from melody towards the manipulation of abstract formulae is clearly traceable. Later Courantes show a move from crotchet to quaver movement, implying an increase of brisure.

An important characteristic to the seventeenth century French harpsichord and lute repertory in general is the use of asymmetrical phrases, syncopations, anticipations and delays of the music in all voices, and the use of the typically French Inègal notes.

4.2. Music for Clavecin:

The references to the Clavecin are rare during the sixteenth century, even into the first decades of the seventeenth century. The most important keyboard instruments on that time in France were imported from Italy or Flanders. During the early seventeenth century the spinet started to decline in social prestige, and apart from an amateur domestic use, its serious practitioners appear to have been a relatively small number of professionals, mainly organists. There was no clear distinction between the repertoires of the harpsichord (spinets) and organs during the early part of the seventeenth century, or in the century before.

From the second half of the seventeenth century, the harpsichord appears as a favourite instrument of the aristocracy and the richer bourgeoisie, equal to the lute. From the written by Mersenne, it is clear that the new style developed by Chambonnières was associated with the harpsichord rather than the spinet, with a greater capacity for resonance and a more brilliant sound.

Spinet and harpsichord were used in the earlier seventeenth century to accompany voices, sometimes in combination with lute and theorbo, but more significant for the development of keyboard repertoire is their association with the viol consort, it seems that keyboard instruments appear to have been an indispensable part of the viol consort. “If the harpsichord was capable of doubling the parts of a consort then it was capable of playing them alone, and indeed a number of viol publications appeared throughout the century with a keyboard performance option”. This transfer of repertoire was not limited to polyphonic music and also included dance movements. Recent research highlights that keyboard arrangements, mostly of Lully's orchestral music, formed a major part of the keyboard repertory during the seventeenth century, and were as important as original pieces in shaping the development of this new keyboard style.

The idea that purely instrumental music during the sixteenth and earlier seventeenth century was written in tablature give us the idea that the harpsichordists on that time were able to read from any tablature, also that one for lute, and makes easier the transfer of repertoire from one instrument to other.

Dance genres were important in both the lute and harpsichord traditions. Until the sixteenth century, dance Suites were not composed in a standard order but were rather set in binary form or grouped in contrasting forms, which was characteristic of the lute style (style brisé). Two lute anthologies published by Ballard in the first half of the seventeenth century were the first to show the standard Suite organization of Preludes, Allemandes, Courantes, and Sarabandes. The organization of Suites by diatonic keys, instead of modes, was an innovation of the lutenist Denis Gaultier.

In France, from the second half of the seventeenth century, the music for organ was totally separated from the music for string keyboard instruments. The differences between the organ and the harpsichord music can be appreciated in the musical forms, in the principal composers and in the places, as we can see the table below:

|

ORGAN |

HARPSICHORD |

|

|

Musical Forms |

Polyphonic works and Pieces for the church services. |

Dances. |

|

Places |

Big French Cathedrals and Churches. |

The Court in Paris and Versailles. |

|

Principal Composers |

Jean Titelouze, François Roberday, Nicolas Gigault, Guillaume-Gabriel Nivers. |

Jacques Champion de Chambonnières, Louis Couperin and Jean-Henry d’Anglebert. |

To have a complete vision of the Courante for harpsichord from the second half of the seventeenth century in France, this research is focused on the three main composers:

- Jacques Champion de Chambonnières.

- Louis Couperin.

- Jean-Henry d’Anglebert.Jacques

- Champion de Chambonnières (c. 1601 - 1672):

Little information is known about Chambonnière’s early education and personal life. From 1632 he appears as Gentilhomme de la Chambre du Roy, a job that his father had already occupied. After Louis XIII’s death, he continued working in the Court. But when Louis XIV chose Etienne Richard as his harpsichord teacher, Chambonnière’s career in the court was less and less important until 1662, when d’Anglebert obtained the Ordinaire de la chambre du Roy pour le clavecin. Despite, he continued working as an instrumentalist in the Court until his death.

We know more than one hundred and forty pieces for harpsichord by Jacques Champion de Chambonnières, and all of them are dances. In 1670 Chambonnières published the two books of “Pieces de Clavessin”, with sixty pieces. The other pieces are contained in different manuscripts, principally in the Bauyn Manuscript, in the Manuscript Rés 89 ter, in the Manuscript 2356 and in the Manuscripts 2348 and 2353.

The pieces published in 1670 were an anthology chosen from the composer’s life work and gathered into groups or suites, defined by the key.

In his pieces, there are examples of the most fashionable dances at that time (Allemandes, Sarabandes, Gigues, Pavanes, Chaconnes…) but in his production, the Courantes stand out in number and in quality. We can find in his music more than seventy Courantes. He uses the normal order for the dances in this period, consist of an Allemande, two or three Courantes and a Sarabande, to which a final piece is sometimes added.

The Courantes by Chambonnières are following the classic model of this musical form, showing a clear ambiguity in the phrasing and in the rhythm and an alternation between the 3 / 2 and the 6 / 4. As is usual in this dance the first part is always shorter than the second one.

He does not use the alternative movement, typical of the lute Courante, in which melody and bass move in parallel thirds or tenths.

As with lute Courantes, some of Chambonnieres's have petites reprises either fully written out or marked with a renvoi.

“Chambonnieres's basses share the irregular scalic structure of the lute Courantes. Chambonnieres is conservative in his use of the melodic type of Courante, in the use of the repeated chords in the cadence patterns and in the melodic structures. A strain typically consists of a characteristic opening figure, establishing the allure of the dance, followed by a series of asymmetrical but balanced patterns of increasing length (typically of 3 - 4 - 7 bars). Some Courantes have a very symmetrical phrase construction. Imitation, where it is used, is most commonly direct, but it may also be inverted or augmented. Doubles are constructed mainly from quaver decoration of the melodic line”.

- Louis Couperin (c. 1626 - 1661):

Most of the information about Louis's life can be found in the work “Le Parnasse François”, written by Évrard Titon du Tillet (1677 - 1762) in 1732, which is a very valuable source of information to know the biographical and professional career of the main poets and musicians of the France of the reign of Louis XIV. We also find important facts about Louis Couperin's life on the “Lettre de Mr. Le Gallois a Mademoiselle Regnault de Solier touchant la Musique”, written by Jean Gallois (1632 - 1707) in 1680. He started his musical studies with his father. Louis was a great keyboard and viola da gamba performer, as well as a composer, when around 1650, according to Titon du Tillet, he visited Chambonnières, who was travelling through the region of Brie. After a small demonstration of Louis’s musical compositions, Chambonnières was impressed with him and insisted on taking charge of Louis's musical training in Paris, thus introducing him into the musical world of Louis XIV's court. With the arrival of Louis Couperin in Paris, he came into contact with some of the leading musicians of the time, like d’Anglebert, Lebègue, Blancrocher and Froberger. In 1653, Louis Couperin became the organist of the Saint Gervais church in Paris, one of the most important and best paid positions in France at the time. Louis Couperin also entered the service of the court as a viola da gamba player and, according to Titon du Tillet, he rejected the offer of work as Ordinaire de la chambre du Roy pour le clavecin, since he was occupied by his friend Chambonnières. During his last years, he was also working for the diplomat Abel Servien (1593 - 1659) in Meudon, as organist and harpsichordist.

Louis Couperin wrote almost his entire oeuvre for harpsichord, but he also wrote few pieces for organ and for ensemble. His production for harpsichord is formed by fourteen “Preludes non Mesurés” and more than one hundred dances. The music composed by Louis Couperin was profoundly influenced by Chambonnières and by Froberger.

As in Chambonnière’s music, we can see all the common dances in Louis Couperin’s music, finding more than thirty Courantes. These dances are following the models of his master Chambonnières, but in the case of Couperin, the dances are longer and with some more elements of counterpoint.

“In structure, the Courantes of Louis Couperin are similar to those of Chambonnieres. Couperin’s tenor often imitates the melodic line, even if the imitation is frequently not exact. These Courantes, are more lively rhythmically than the examples of Chambonnieres. His Courantes keep close to the standard three part format, although some have much four-part writing. Cadence formulas may have a slightly more style brisé form than in Chambonnieres”.

There are two principal sources for the Louis Couperin’s harpsichord music, the Bauyn Manuscript and the Parville Manuscript.

- Jean-Henry d’Anglebert (1629 - 1691):

D’Anglebert largely escaped the attention of contemporary music writers as Jean le Gallois and Titon du Tillet (unlike Louis Couperin and Chambonnières). Even Michel de Saint Lambert makes reference to d’Anglebert strictly in the context of the published book “Pieces de Clavecin”. This means that we know very little about d’Anglebert’s life and his formation. He started his career in Paris as organist at the Jacobin church in the Rue Saint-Honoré and working as a harpsichordist at the Court. From 1660 he obtained the position as a harpsichord player for the Duke of Orléans, Louis XIV’s brother, and from 1662 he is the working as Ordinaire de la musique de la chambre du roy pour le clavecin.

“Pieces de Clavecin” was published in 1689, two years before the composer’s death, and this volume resumes d’Anglebert’s achievements as a composer, harpsichordist and teacher.

“In general, there is little in d’Anglebert’s Courantes to recall, these Courantes employ the common formal and textural principles of the keyboard tradition. The prominence of the melodic line is expressed in his very profuse ornamentation, fully notated or indicated with signs. The melodic decoration (that contributes to the rich texture), the rhythmic solidity and the full texture, are the most important are characteristics of d’Anglebert's style. We can find fewer elements of lute style than in Louis Couperin’s examples”.

D’Anglebert provides in the Manuscript Rés 89 ter. doubles for some of the Chambonnière’s Courantes.

The Courantes are by far the largest group of dances in the d’Anglebert's lute arrangements from the Manuscript Rés 89 ter. All of these dances are attributed to Ennemond Gautier.

In d’Anglebert’s Courantes, the right hand reflects the lute melody lines with occasional chords for accentual purposes and the lute's ambiguity of melody and alto part, but the left hand is generally worked in the brise style with two parts of the standard keyboard format.

One important characteristic of d’Anglebert style is that he tends to fill out broken chords with acciaccaturas, as he explains in his treatise “Principes de l’Accompagnement”.

There are two main sources for the Jean-Henry d’Anglebert’s harpsichord music, the “Pieces de Clavecin” (1689) and the Manuscript Rés 89 ter. We can find also pieces by d’Anglebert in the Bauyn Manuscript and in the Parville Manuscript. In all these sources there are, at least, ten Courantes.

Resume:

After the study and analysis of this music, we can obtain some conclusions for making a resume about the Courante Françoise in harpsichord repertoire. As we know, the Courante is the slowest (Grave) dance of the seventeenth century French Suite and we can find some common elements in all these pieces:

- Time signature 3 shows us the 3 / 2 bar, with three slow beats per bar.

- The tempo in the Courantes for harpsichord could be slightly faster than in other examples (lute, viola de gamba and ensemble pieces).

- Ornamentation, principally in the melody line, should follow a vocal way, full and varied.

- Bass lines should provide the harmonic foundation of the movement.

- Courantes can be played with great freedom, but the tempo has to be stable.

- As a general rule, the “Inegal notes” are quite unsuitable on these dances. But the Inegal can be appreciated through the Iamb and triple Dactyl feet.

- Flexibility or ambiguity that “Proportio Sesquialtera” can offer. The juxtaposition between the meter 3 / 2 and the 6 / 4 can be explored by the performer.

- Use of petites reprises, that were useful in danced Courantes to create the pair number of bars.

- Continuous melody lines and broken texture (style brisé) in the accompaniment.

- Passing modulations and retarded cadences are typical elements of these dances.

Even existing some different aesthetic elements in the Courantes of each composer, it is clear that the style is the same and we can analyze the Courantes from the second half of the seventeenth century as a unit.

4.3. Correntes and Courantes in Harpsichord music:

Some of the firsts important examples of Correntes are in early sources as “The Fitzwilliam Virginal Book”, “Il secondo libro di toccate, canzone, versi d’himni, Magnificat, gagliarde, correnti et altre partite” by Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583 - 1643) and “Terpsichore” by Michael Preatorius (1571 - 1621). In the second half of the seventeenth century Italian composers, as Michelangelo Rossi (c.1601 - 1656), Bernardo Pasquini (1637 - 1710), Bernardo Storace (c. 1637 - 1707) continued composing Correntes.

There are a lot of examples of French Courantes in harpsichord Suites and collections by:

- Jacques Champion de Chambonnières (c. 1601 - 1672)

- Louis Couperin (c. 1626 - 1661)

- Jean - Henry d’Anglebert (1629 - 1691)

- Jacques Hardel (c. 1643 - 1678)

- Étienne Richard (c. 1621 - 1669)

- Henri Dumont (1610 - 1684)

- Nicholas - Antoine Lebègue (c. 1631 - 1702)

- Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre (1665 - 1729)

- Louis Marchand (1669 - 1732)

But examples of French Courantes are not only found in French sources. German keyboard composers also adopt this dance in their music, Composers as:

- Johann Jakob Froberger (1616 - 1667)

- Johann Adam Reincken (1643 - 1722)

- Johann Pachelbel (1653 - 1706)

- Dietrich Buxtehude (1637 - 1707)

- Johann Kuhnau (1660 - 1722)

The Courantes by François Couperin (1668 - 1733) and Jean - Philippe Rameau (1683 - 1764) take this form to the extreme with great harmonic tension and very developed ornamentation. During this period the Courante was already decaying in popularity.

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685 - 1750) distinguished in his Suites between Corrente and Courante, so there are examples of Correntes in the First, Third, Fifth and Sixth “Partitas” for harpsichord, in the Second, Fourth, Fifth and Sixth “French Suites”. These movements are written in 3 / 4 or 3 / 8 with a simple texture, clear harmonic and rhythmic movement and a virtuosic figuration in the upper voice. The examples of French Courantes in Johann Sebastian Bach’s music are found in all the “English Suites”, in the First and Third “French Suites” and also in the Second and Fourth “Partitas” for harpsichord, among others. These Courantes by Bach are less ambiguous rhythmically than the French examples.