UNDER THE MIRRORING SURFACE

Adam Kraft, 2018

“Le droit à la ville se manifeste comme forme supérieure des droits: droit à la liberté, à l’individualisation dans la socialisation, à l’habitat et à l’habiter. Le droit à l’oeuvre (à l’activité participante) et le droit à l’appropriation (bien distict du droit à la propriété) s’impliquent dans le droit à la ville.”

(Lefebvre, 1968)1

*

Bestand (Stock);

Aluminum plate (2mm thick)

Fence (4mm steel wire)

Flake board (12mm)

Paver (50x350x350mm, ~10kg)

Pine board (70x150mm/45x230mm)

Plaster sheet (12mm)

Plastic crate (150x400x600mm)

Plywood (22mm thick)

PVC banner (~500gsm)

Rebar (6/8/10/13mm)

Scaffolding pipe (Ø 48,3 mm, steel)

+ coupler (swivel or straight)

Square pipe (40x40mm, aluminum or steel)

This is the palette for my crafting & building practice. It contains the most common elements for construction work that are possible to procure in the streets of Berlin (and many other cities experiencing similar economic transformation); plywood, rebar, scaffolding pipe — simple elements of our (re-)built environment. The work is concerned with taking advantage of existing systems and machines, rather than manufacturing new things; in this case a ‘détournement’2 of basic material elements from which the city is built. As stated by Lefebvre; the right to the city exists only as people appropriate it.

Skip

An improvised cart with a dumpster lifted onto it, pushed through the streets for the purpose of collecting bulky building material. The interventional de-imagineering of the city begins with procuring, deconstructing and contesting these building elements.

The right to the city needs to begin with the right to imagine the city.

In my research I’m investigating methods to ‘de-imagineer’ and further to partake in the shaping of an urban commons (mentally and materially), through practices of altering and re-purposing existing structures. The work is both informal and transgressive in its methodology, with the core intention to investigate and participate in the shaping and making of the social city. Art and research can provide keys to accessing such a city in the making; a space where we can challenge the preconceptions of what is possible, and to imagine alternative strategies for the creation of realities. As the concept of ‘imagineering’ suggests; it is imagination-engineering possibilities to hypothetically look behind reality and shape it. Imagination, as the thought material that potential realities are made from.3

As the term ‘imagineering’ is heavily connected to its use in the creative economy, I suggest the wordplay of ‘de-imagineering’ (the deconstruction of imagination-engineering). I argue that the production of imagination is fundamental for the change of current conditions and requires appropriation. It’s an anarchist posture, denouncing everything that cuts us off from and diminishes our own power to act.

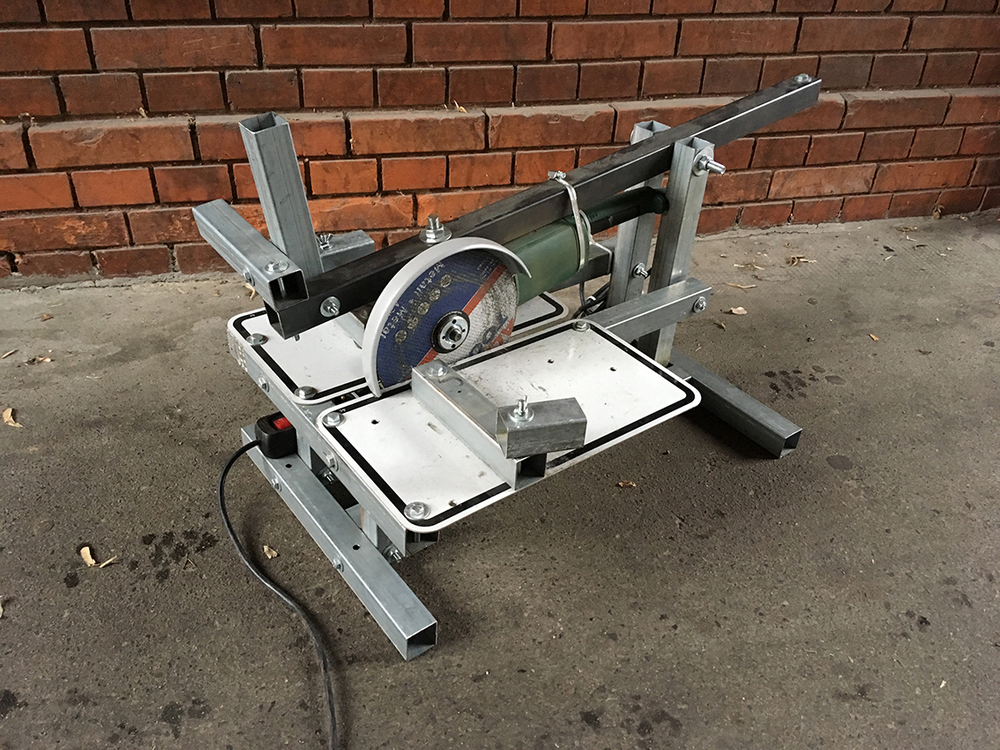

XYZ Pipe Cutter

Not only imagination is held in the deposit and account holdings of corporate and commercial actors, but so are many of the tactics that are designed to contest this hegemony. Counter culture is continuously being transformed to fit as capitalism’s sanitizing tool in “redeveloping” cities, co-opted and instrumentalized in processes of gentrification. In my work this manifests the ethical issue of having a practice that risks fueling the dominant system, what the Situationists referred to as ‘récuperation.’4

Is it feasible to maintain and sustain with criti-

cal action? There are concepts floating around ar-

guing for such; critical spatial practice is one

of them. But the practicalities are abstracted to

the degree that they seem pure speculation. Possibly this is a strategy to remain out of reach from neoliberal co-optive machinery but its consequence is to prohibit a radical challenge to the current condition.

Where is the ‘Representational Space’ — Lefebvre’s definition for “spaces the imagination seeks to change and appropriate”5 — where everything could come together; the abstract and the concrete, the real and the imagined, the knowable and the unimaginable, mind and body?

And further on, how can this be dealt with in a research practice?

“Should we move beyond academic texts to texts in other modalities? And not just texts and figures, but bodies, devices, theatre, apprehensions, buildings?”

(Law, 2004)6

This political reading of a contemporary urban status brings my project to a liminal position; between a public interventional practice of

‘de-imagineering’ and a private knowledge production/distribution within an ‘undercommons’ (“The art of the undercommons is the wisdom to make worlds while obfuscating subversive knowledges from recuperation”).7 This necessity, to build or inhibit new forms of social relations (a new commons), has had a recent revival due to the waves of privatizations, enclosures and spatial controls. The public practice supports on the one hand an open source utility for parts of the knowledge that has been organized, and the private practice acts as a strategy, outside of the vision, to counter recuperation.

“There is, in effect, a social practice of commoning. This practice produces or establishes a social relation with a common whose uses are either exclusive to a social group or partially or fully open to all and sundry. At the heart of the practice of commoning lies the principle that the relation between the social group and that aspect of the environment being treated as a common shall both be collective and non-commodified — off limits to the logic of market exchange and market valuations.”

(Harvey, 2012)8

‘Underground’ and ‘invisibility’ are advocated as key concepts throughout my research, both spatially and culturally (as within an undercommons). It’s promoting a space and a practice — real and imagined — whose lines and contours are undecidable and therefore contestable, evading cultural co-optation.

”invisibility not only as a consequence of certain political systems, but also as a vital means for countering such systems – for suspending the logic of capture with the potential of the ‘not-yet’ (…) invisibility is not only a tactic of counter-public formation; rather, invisibility shifts the paradigmatic terms by which public power is to be understood. By bringing into relief the regime of visibility as an apparatus, a biopower, invisible practices amplify the blind spots and the negativities within which other imaginings and logics, poetics and politics may take shape.”

(LaBelle, 2017)9

Hus AB

In early 2003 I built a shelter together with fellow artist Klara Lidén. It was installed by the Spree, next to Ostbahnhof, in what used to be the ‘Death Strip’ between East and West Berlin. We built the informal structure working night shifts, while we spent daytime scavenging construction material from the neighboring streets. It was installed in a slot of the riverbank, camouflaged with the surrounding landscape — a hide-out in the wasteland of a political epicenter. As expected, the house was eventually demolished. The only remains to this day are the holes which we drilled into the concrete.

15 years has passed since the ‘Death Strip-shelter’ was removed. Today Berlin is a socially and structurally transformed city, three decades after the iconic fall of the wall. A luxury living edifice is today towering at the location of the former shelter.

To research and reclaim the lost presence of a representational space I’m currently performing an inventory of the Spree flood bed, up along the inbetweenness of the former borderland. Under the mirroring surface constructions are being submerged and assembled for the purpose of a moon pool shelter; an underwater breathing space with an entrance from below, in a space in constant flux.

My research takes place in the shadows of public space; in spaces which are palpable yet invisible, social but disjointed at the same time. A space where ephemeral transformations takes place. It investigates how — and if — invisible interventions can be disseminated to provide a widening of an emotional space, an other awareness of possible acts and possible environments that surround us at all times. There are similarities with phenomenological research methodology; describing a lived experience of a phenomenon and allowing the method of analysis to follow the nature of the data itself and thus the possibility of theory-independent data. Mapping invisibility is a ghostly and elusive undertaking, in terms of tracking down and verifying underground activities. Not least because, as I’ve experienced it, these activists methodically wishes to remain below radar.

The circulation of my research contains a paradox within, it is not primarily intended to be exclusive or coded, as in the case of this article or with the promotion of the concepts of invisibility and of the ‘undercommons.’ At the same time I’m performing actions in public space with the core intention of producing unanticipated temporal shifts in the way we imagine and attach ourselves to the city. The paradox lies within the dichotomies of public/private, sharing/protecting, visibility/invisibility. It appears as a deadlock position; by publicly contributing to the sharing, shaping and creating of the democratic city you will be supporting it with value, which in turn will stand exposed to the hegemony of commodification. Contrary; by addressing but the few, as within an undercommons, the undertaking becomes exclusive and is likely to only be for the benefit of a chosen few.

“The risk for movements organizations to become co-opted or partially integrated into a neoliberal urban model has only become more acute in the most recent phase of urban development. (…) The new ‘creative city’ policies make use of (sub)cultural milieus in their branding strategies and harness them as location-specific assets in the intensifying interurban competition. Clubs, buildings, open spaces, and other ‘bio-topes’ that have been furbished and spiffed up by squatting anarchists or temporarily used and made interesting by precarious artists are sought after in urban branding strategies, frequently yielding good bargains and advantages for activists who initially were struggling in the name and for the rights of marginalized groups beyond themselves. (…) neoliberal urban policies have proven particularly successful in hijacking rebellious claims and action repertoires, and in integrating those into market-based creative concepts designed to enhance the competitive value of locational assets.”

(Mayer, 2012)10

This unavoidably expands into a number of ethical issues; concerning confidentiality, exclusivity, anonymity, and matters of social sustainability. In my own interventional practice as well as in my work of tracking and following european urban underground collectives, working with e.g. unauthorized tunneling, cartography, infiltration, obstruction, defacement, subcultural programming, (an-)archiving and informal distribution of knowledge.

“Questions of the commons, we must conclude, are contradictory and therefore always contested. Behind these contestations lie conflicting social and political interests. (…) At the end of it all, the analyst is often left with a simple decision: Whose side are you on, whose common interests do you seek to protect, and by what means?”

(Harvey, 2012)11

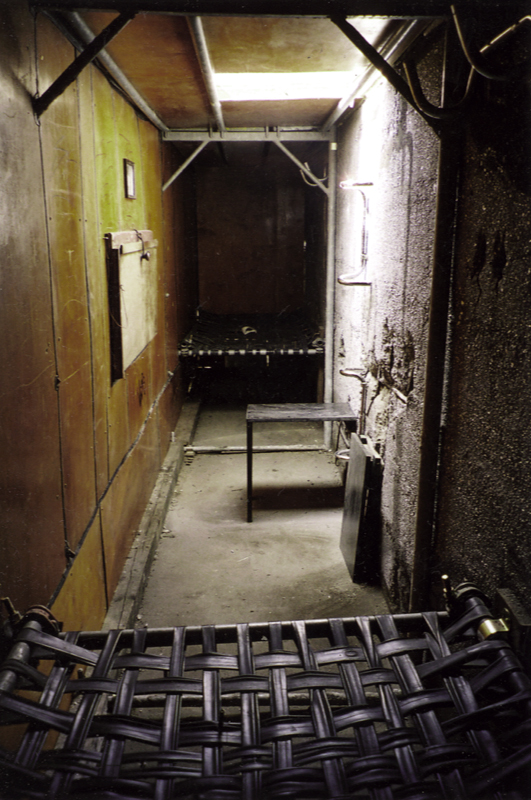

End of the Line

In the early spring of 2003 a trilogy of transgressive spatial interventions were initiated at the Copenhagen Central Station — all performed in close collaboration with my working partner E.B.Itso. With the first work we set up a secret apartment beneath the waiting hall. As the space was discovered during a big renovation of the station in 2007, the chief inspector was interviewed on danish television. State workmanlike he politely informed the public that this kind of intervention would definitely not be possible to be reproduced in the future, with the new security measures that had gotten installed. Something we understood as a challenge and accepted.

During one year we worked two hours a night, in the gap of the working shifts of the maintenance employees, using their clothing to render our endeavor invisible. With this second intervention we were able to reclaim our residency with a new space; equipped with a DIY elevator, two beds and running water. To this day still not discovered.

With the third and final work we removed a small track-sided shack with the intention to bring it as far up north as the tracks led us. Escaping from the city was triggered by a spiraling experience of exclusion, homogenization and standardization of city life. As it was decided that DSB (the Danish State Railways) was about to privatize large parts of its’ structures, including a big chunk of the train yard adjacent to the Copenhagen Central Station, we had not only reason but also possibility to perform our experiment. As train traffic was redirected we suddenly had the tracks leading away from the city for ourselves, prior to the pending machinery of urban redevelopment. We lifted the shack onto a bricolaged wooden cart and pushed it as far as we could, away from the city. After having rebuilt the interior space we just had to wait for an opportunity to continue our journey.

In October 2012 we arrived on the far side of the Arctic Circle, having travelled clandestinely in the shack on a flat wagon of a rumbling cargo train. We placed the shack at the very end of the train tracks, expecting another reality. But already a month after we occupied this very location it turned into yet another major site of redevelopment. This time with the construction of one of the biggest suspension bridges in Europe, all in an attempt to stimulate economic growth — leveled with tarmac and concrete, making way for tourism and global logistics. The shack was continuously being displaced and pushed along with rubble and debris as the redevelopment program progressed.

As an extension of my work the narration/

dissemination strategies primarily follows the same logic of reassembling, rebuilding and reworking existing structures. It is a take-what-you-find/use-what-you-get type of bricolage with a taken/given set of limitations, providing a stance in which a resistance and a part-taking in the shaping of the urban coming to be interlocked with. A spatial practice with an intent of developing social storytelling techniques, below and above surface.

During the autumn the construction of the bridge was about to be completed. Without giving up the idea of docking to a place where formal structures of control could be eluded, we moved the shack further, out into the neighboring archipelago and the very edge of the Eurasian tectonic plate.

Geologically, we found small clues in the remains that had been washed ashore from the bathypelagic depth — relics of an unknown fauna — onto the sheltered coves not far from the new position of our shack. I find it promising that science has provided us with more knowledge of the surface of Mars than of deep sea ecology. The geological and the cultural underground strives to provide us with a sliver of unmapped and unexploited territory of wildness; namely in the imaginative force of the yet invisible.

*

1. Henri Lefebvre, “Le Droit à la ville” (1968)

2. The Situationists proposed ‘détournement’ as a methodological answer to ‘récuperation’ (see footnote 4). It was the appropriation of images or ideas and the changing of their intended meaning in a way that challenged the dominant culture. This method is not about ownership but about having access to and influence over a collectively produced reality.

3. Imagination, as described by Patrick Reinsborough in “Decolonizing The Revolutionary

Imagination” (2004);

“Imagination conjures change. First we dream it, then we speak it, then we struggle to build it. But without the dreams, without our decolonized imaginations, our efforts to name and transform the system will not succeed in time.”

4. Récuperation; “the activity of society as it attempts to obtain possession of what negates it”. “Situationist International” (No.1, 1969) http://www.cddc.vt.edu/sionline/si/faces.html

5. Henri Lefebvre, “The Production of Space” (1991)

6. John Law, “After Method — Mess in Social

Science Research” (2004)

7. Stevphen Shukaitis, “The Wisdom to Make Worlds: Strategic Reality & the Art of the Undercommons” (2016)

8. Christian Schmid, “Cities for People, Not for Profit,” Chapter 4; “Henri Lefebvre, The Right to the City, and the New Metropolitan Mainstream” (2012)

“As Lefebvre stated succinctly, theory must be steeped in practice in order to become effective. In practical terms, this means that theoretical analysis must be confronted with practice. Doing so is always a social act and an intervention in social reality, and thus also a confrontation, an exchange, and an encounter where theory itself is transformed.”

9. Brandon LaBelle, “The Invisible Seminar” (2017)

10. Margit Mayer, “Cities for People, Not for Profit” Chapter 5; “The ‘Right to the City’ in Urban Social Movements” (2012)

11. David Harvey, “Rebel Cities” (2012)