Woven Fingerprints

The premiere of a new piano concerto is a collective process, and all such collaborative projects see the emergence of power structures and hierarchies. Who decides how the music should sound? How should we organise the work and how should the new piano concerto be presented?

The hierarchical relationship between soloist and conductor in traditional piano concerti is a well-known minefield. At times, the most senior or most ‘famous’ person in the partnership has the last word about how the work should be played. David Itkin describes the hierarchical relationship between soloist and conductor in his textbook on conducting:

If you are working with a young person who is not yet a significant soloist you are probably in a position to teach a bit, so go ahead and do so; when you are working with a lateral colleague you should feel free to speak your mind as long as you do it in a respectful and affable way; when you are working with a soloist who is clearly above your station you should make your request with reasonable deference, and if the soloist doesn’t want to change what she is doing you close your mouth and do the best you can (Itkin, 2014: 9-10).

Artists who are engaged for their fame and their ability to ‘pull in the crowds’ to a concert, will, following Itkin, be the actors with the ultimate power to make decisions.

In the legendary duel between Glenn Gould and Leonard Bernstein over Brahms’s Piano Concerto no. 1 in New York in 1962, Gould was allowed to choose the tempi, but Bernstein mounted the podium before the performance to announce to the audience that he did not agree with Gould’s choices:

You are about to hear a rather, shall we say, unorthodox performance of the Brahms D Minor Concerto, a performance distinctly different from any I've ever heard, or even dreamt of for that matter, in its remarkably broad tempi and its frequent departures from Brahms' dynamic indications. I cannot say I am in total agreement with Mr. Gould's conception and this raises the interesting question: What am I doing conducting it? 1 (Bernstein, 1962)

Gould goes on to perform the concerto with the full orchestral score in front of him on the music stand. His attitude testifies to his desire to have decision-making power over the entire musical conception, not just the part for which he was personally responsible but, in effect, the approach to be adopted by the orchestra as well. Was such an awareness of roles a threat to Bernstein’s position in the hierarchy? His disclaimer before the performance suggests that he at least partly felt the need to wash his hands but nevertheless he was prepared to go ahead with the performance and share in an experiment whose ‘research question’ was Gould’s, not his.

Hierarchies in music

The Gould/Bernstein case is a fascinating mixture of competing egos on the one hand and the shared commitment of two artists to exploration and innovation in their art on the other. It remains an interesting item in the archive of recorded music-making because of its many exceptional features. Under most performing situations, idealism and arrogance are generally both subordinated to pragmatism. Since the performance of new piano concerti usually involves very short rehearsal time concentrated just before the premiere, efficiency is crucial. Fredrik Engelstad describes the importance of hierarchies in high-pressure situations:

Although it is desirable to break hierarchies down, it is no simple matter in practice. ... A clear hierarchy means the allocation of responsibilities and precise requirements as to the type of expertise the people involved at different levels are expected to bring along. It can also provide support in difficult situations. In organisations without explicit hierarchies, this support will be missing. (Engelstad, 2005: 94, my translation.)

A clear hierarchy with the conductor at the top of the pyramid is sensible just because it allows everyone – orchestra, soloist, and conductor - to ‘reach the goal’ of getting the performance ready for performance in time.

What’s more, the complexity of some new music can make it virtually impossible for musicians to work properly without the clear leadership of a conductor. In the performance of Ausklang, I depended on many cues from the conductor to see where I was as the piece progressed. In Concerto for piano and ensemble by John Cage (1958) 2 the conductor simulates a ‘clock.' The movement of his arms resembles the hands of a clock marking the intervals and cueing the orchestra. The conductor was our marker in the light of his ability to tell us where we were as the performance of the piece evolved. In my experience, musicians tend to become more dependent on a conductor when the music expresses new aesthetics, rather than in older works where everybody knows the score well and feels they mostly can navigate it for themselves with the conductor setting a few interpretational parameters but, in the performance itself, playing a predominantly confirmatory or corroborative role.

A premiere is a risky business. Conductors can obviously make mistakes, with the result that the composition can collapse. Cathrine Winnes exclaimed in a radio interview: ‘This is a concerto for conductor and orchestra!’ in reference to the piano concerto Theory of the Subject because the conductor, in addition to conducting a challenging score, had to coordinate live video and a PowerPoint presentation on a screen behind the orchestra during the performance (2016). Conductors of contemporary piano concerti are in a vulnerable position and have an enormous responsibility, which, paradoxically, also gives them a great deal of power.

Unlike many soloists, in my work, I want to take part in more of the processes surrounding new piano concerti because they need, in my experience, particular attention if they are to function successfully under the same constraints as old, familiar music. New music is not as ‘quality-assured’ as canonical piano concerti, and the work we do together before a premiere is essential for the composition’s future life. Will the music be performed ever again? Our performance is the composition’s very first encounter with the world and, given the tight schedules we have to work under, our rehearsal is, as I see it, not dissimilar to extreme sports.

I want to find out if my expanded understanding of my role and my close relationship with the music give me greater decision-making authority, and to explore whether I might use this power in a way that benefits the music. I shall describe my place in the hierarchy in light of the work on the piano concerto Woven Fingerprints, a premiere that was cancelled and a work which, at the time of writing, is not yet performed. 3 I posed myself the following question:

Does my greater understanding of my role alter my place in a wider, collective sense?

The process

The piano concerto Woven Fingerprints by Therese Birkelund Ulvo for two soloists and orchestra was commissioned by Kristiansand Symphony Orchestra (KSO) in 2012 to celebrate the centenary of Norwegian women’s suffrage in 2013. I was invited to be one of the soloists, alongside pianist Andreas Ulvo. 4 When the composer became pregnant with her second child, and it proved impossible to find a date that suited everybody for an early workshop in the anniversary year, the first performance was postponed.

Following this initial postponement, I worked at organising a new attempt. The soloists’ contracts had already been signed, and since there had been changes in the orchestra’s senior management, I felt a new initiative would be critical to getting the project back on track. I invited myself to Kilden Concert Hall in 2014 to discuss with the management different approaches and the possibility of organising an initial workshop. A schedule was agreed, and it was exceptionally generous. KSO set aside an entire day for the workshop six months before the world premiere, slotted for January 14, 2016. I have never experienced such generous and satisfactory working conditions for a new piano concerto.

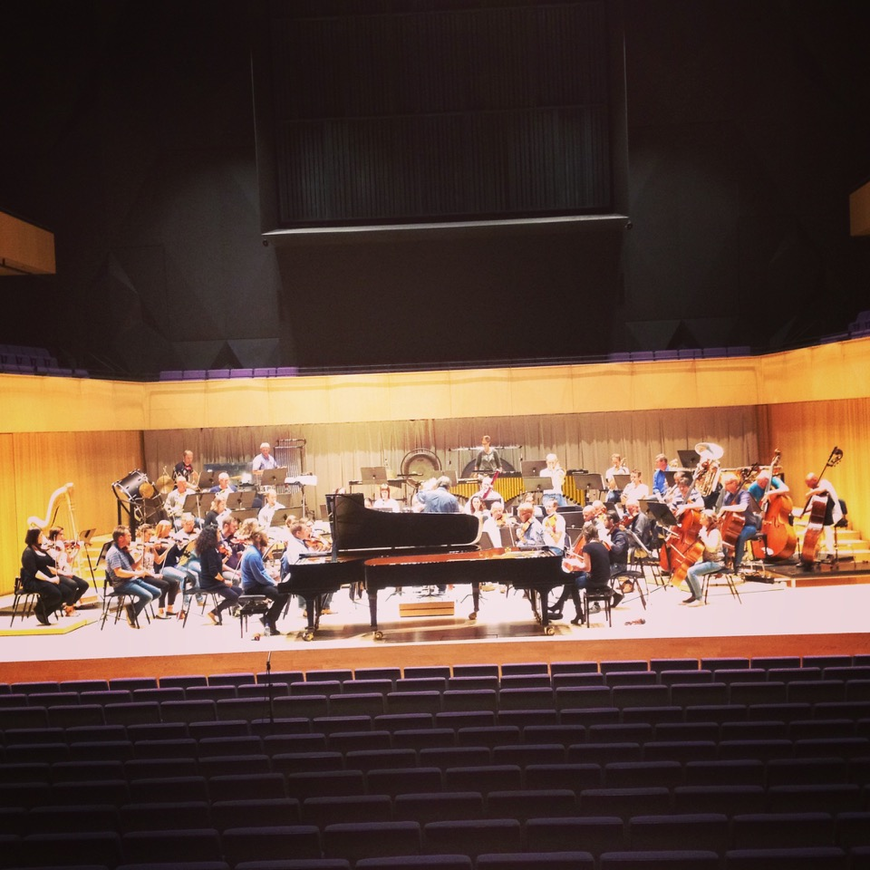

Ahead of the August 2015 workshop, the composer and I worked on my solo part. Birkelund Ulvo makes music with particular musicians and their characteristics in mind, and for her, collaboration is an integral element of the compositional process. The composer and I discussed the possibility of experimenting during the workshop to make as much use of the material as possible. We decided on a rather ‘disciplined’ workshop for the orchestra, while we soloists could improvise or put our material together in various ways on top of the orchestra’s music, to make sure everything was tried and tested. Before the workshop, we also had a brief meeting with the conductor, where he went through notation details in the score. At the orchestra’s workshop in Kristiansand, we worked from musical sketches. Ulvo made recordings for use later in her work on the material. The material was sparse but gave us a clear idea of the composer’s aesthetic architecture. We also got used to the hall’s acoustics, the concert grands, the conductor’s style and the sound of the orchestra.

Work continued during the autumn with several workshops between soloists and composer on developing and finalising the soloists’ material. It was an exciting process. It was inspiring to hear how Andreas Ulvo improvised over the material and exciting to observe the difference in our approaches to the written score. The most challenging thing was for us both to achieve the same sense of timing because sometimes our actions had to take place at the same moment. It seemed a sensible decision to spend a long time on getting the articulation just right and on playing together. I was happy with the prospect of avoiding the stress that typically accompanies premieres especially because, where a new work is in evolution right up to the date of the first performance, a lot of new material is likely to turn up just before the premiere, and you have little choice but to pack more into the practice sessions.

Then came the shock. Ulvo’s husband was diagnosed with a severe illness only twenty days before the composer’s deadline on 13 November 2015. Despite the circumstances, Ulvo managed to finalise the score, albeit electronically rather than, as initially agreed, on a printed score – only a week after the deadline. The orchestral parts were sent off to the music copyist at the same time as the electronic score was finished.

This delay produced shock number two: the orchestra’s management decided to cancel the piano concerto because the music had not been delivered on time, despite continuous updates on the severity of the disease and nature of the situation. The very same day the management sent us an email announcing the cancellation, they also replaced Woven Fingerprints with Dvořák’s Serenade for winds, cello, and double bass.

I took immediate action and tried to get the management to reverse their decision which, in my opinion, was entirely unnecessary because everybody involved knew the material well and the postponement only added an extra week to our work. I called the conductor the same day in the belief that I, as a soloist, had some influence. We had prepared the work exceptionally well, I argued, for the world premiere, and were well-equipped to tackle unforeseen situations, because the workshop had given us a physical understanding of what the composer’s aesthetics embodied. As soloists, we knew our parts well having worked on the piece throughout the autumn. The conductor was not to be moved, however. He had planned to start his study of the score right after the deadline, something he was unable to do without a printed score. And he was otherwise fully booked up to the day of the premiere, January 14.

I wrote at once to the management to explain how well everything had been going as seen from what, in my mind, was my central position as one of the soloists. It was extraordinary that the composer had managed to finalise the work in the midst of an acute crisis. I asked the management to reverse their decision. The work was ready, and it was only two months or so to the concert! The management replied that they were willing to discuss whether it might be feasible to re-programme the work when the score and parts had been delivered. But there was no way they would revoke the cancellation.

The decision divided us. The conductor stood on the side of the management and the cancellation; the ‘losers’ were the music, the composer, and the soloist. Their refusal to talk and work with us all to resolve an unforeseen difficulty and the rapid replacement of Woven Fingerprints with the Serenade only served to harden our positions. As a soloist, I had no influence at all in the wider context. This was further underlined when I approached the management after the Christmas break about their procedures in relation to soloists when concerts are cancelled. There was no response. Two weeks later I sent an invoice. This time, KSO responded immediately asking whether we could wait with our invoices until a new – albeit unspecified – performance date had been decided for the new piano concerto, possibly in 2017. Andreas Ulvo and I both responded negatively to this proposal since we had both included our income from the performance in our accounts for 2016. The management refused to pay our fees. Finally, we asked the Norwegian Musicians Society (MFO) to step in. We were paid in April and our contact with KSO ceased. Elected leaders at The Norwegian Society for Composers for the year 2015/16 did virtually nothing to help us get the decision reversed.

Reproducing musicians

I believe we have a collective responsibility to develop our musical tradition and avoid stagnating. The major bodies in the music sector are subsidised by the state to commission and premiere new music and to offer fresh music to the public. A survey by NKF 5 in 2011 showed that Norwegian and foreign premieres accounted for only 2.08 percent of music performed by the major Norwegian orchestras in the seasons from 2004 to 2007, measured in terms of duration.

At the heart of new music is a principle: the people involved must be willing to think in new ways. When we commission a new work or accept a soloist engagement for a world premiere, no one knows beforehand whether we will ‘like’ the music or feel comfortable playing it. When we commission or engage in, a new work, we do not know how the music will sound or the challenges we will face as we work on it. The paradox is that it is precisely this unpredictability that is new music’s strength – it is often at the point at which we cross a limit in ourselves that new knowledge can be won and the discipline progress.

Entirely new works are vulnerable creatures, both in themselves, because they have not been ‘tested’ in the real world, and because they are created by living people in a dynamic, collective process. The situation requires those involved to show trust in others and be acknowledged as dependable.

[W]hoever wins the confidence of others, will also see opportunities they would otherwise not have had, opportunities they can abuse or make use of more or less competently. It may be difficult to get them to accept responsibility and redress whatever they have done wrong. If the recipient of trust is reliable, things will be done which the person investing their trust either cannot or will not do, but which is still to their benefit. But the basis for trust can also be unsound so that the person who has invested their trust is the one who loses out. On does not always enter into such relationships on the basis of conscious choices. Sometimes one ‘grows’ into them, as children do. Sometimes one is forced into relationships because there are few other options. There may be reasons for the vulnerability that stems from an inner connection between trust, power and fallible contextual definitions. Trust neither eliminates nor reduces these risks. It helps to establish them, insofar as one leaves something – sometimes oneself – in the care of others. Trust does not decrease the risk. It creates danger. (Grimen, 2009: 66, my translation)

A trust deficit leads to insecurity. The world premiere of a new piano concerto is a risky business because the music is untried and demands something new of us all. A great deal is at stake; concerts are costly. We are not sure whether the performance will succeed; we are entering an unknown territory and can end up losing face.

Insecurity makes us want to protect ourselves. The repertoire of most orchestras and soloists consists primarily of old music that long since has passed its quality assurance test. A culture has grown up around the reproduction of ‘successful repertoire.' It seeks to avoid complicated experiments by cultivating ‘Teflon’ concerts with virtuoso soloists. Christian Blom launched the concept of reproducing musicians in a discussion of soloists and orchestras who rarely, if ever, perform new music. A reproducing musician takes no responsibility to extend or expand a tradition by performing new works. Reproducing musicians do not take the risk of performing new works that may be judged as a total failure – or as brilliantly innovative.

In 2012, Morgenbladet reviewed my CD Serynade:

Serynade is the outcome of a deep study of modern sound techniques. […] Ellen Ugelvik has ended up in the shadow of Leif Ove Andsnes, Håvard Gimse, Christian Ihle Hadland, Håkon Austbø and the other so-called great pianists in this country because she thoroughly and consistently has concentrated on contemporary music. Rather than play Beethoven’s sonatas, Ugelvik has studied performance techniques, like plucking strings inside an instrument, hitting and scraping a concert grand, using the pedal as a percussion instrument or playing at insane levels of virtuosity in the contorted patterns produced by non-tonal music. (Andersson, 2012: 35)

Performances of contemporary music, suggests the reviewer, are not held in high esteem in our field. Contemporary music has no ‘superstars’ comparable to some of the performers of the old piano concerti. Contemporary music has been assigned an undeserved place alongside canonical music, rather than a central position as a natural extension of our musical tradition. Contemporary music is considered a separate genre, with its practitioners performing in their areas. As the project period progressed, I have noticed several indications that institutions see contemporary music as second-rate rather than a burning priority.

I have in some cases talked to orchestra managements to try to persuade the chief conductor of the symphony orchestra to conduct a premiere, with no success. I have noticed that new Norwegian instrumental concerti are sometimes scheduled for the ‘short weeks,' such the four-day week after Easter, shortening the rehearsal window for the new music. Sometimes Norwegian premieres of instrumental works have fallen on the same day, at least in Oslo. The piano concerto Concert Piece in three parts, commissioned to celebrate the bicentenary of the Norwegian Constitution in 2014, was rescheduled for performance a year after the anniversary. The Ensemble Allegria cut rehearsal times for at the tips of my fingers / on the tip of my tongue in favour of the other (older) works in the same concert. Very few students specialising in ‘classical piano’ have any contemporary works in their repertoire. And the KSO cancelled the only premiere of the 2015/16 season because the score and parts were delivered one week after the deadline. The KSO replaced Woven Fingerprints with a work by Dvořák rather than programming a different composition with a similar aesthetics.

The fact that the KSO saw it as unnecessary or inappropriate to pay our fees after cancelling the soloists’ engagement is more than just a mercenary issue. It also implies an assumption that the musicians that do work at the pioneering edge of new music, thus putting themselves at artistic risk, should adopt the same attitude to their financial wellbeing. In the same way that orchestral management regards canonical repertoire as its money-earner and contemporary repertoire as something they can sometimes indulge in as a ‘loss-leader,' they transpose the same attitude to the way they treat artists in the two kinds of repertoire. Nobody would think of withholding a soloist’s fee for a concerto from the standard repertoire that was cancelled as the result of a managerial decision.

Among the issues this reveals is that the tendency for musicians to focus either on mainstream repertoire or new works gives rise to different attitudes and approaches to these two groups. The same discrepancy that the 2012 Morgenbladet review of my CD Serynade identifies from the perspective of reputation applies to assumptions about remuneration. As a passionate champion of new music, it is true that I do what I do first and foremost for idealistic reasons. I am sure that the musicians who concentrate on core repertoire would argue that their motivation, too, comes primarily from their art. And yet their status as professionals entitled to appropriate financial reward is somehow more secure than is the case for those of us working almost exclusively with contemporary repertoire.

What is to be done about this? One solution would be that musicians engaged with a contemporary repertoire as a matter of course. This, in turn, would require different attitudes and different curricula inside conservatories and music schools. If contemporary repertoire were a familiar part of every newly-trained musician’s practice, they would find it more natural to program it in their concerts alongside more traditional works (perhaps looking for illuminating juxtapositions in the process). This would put more new music before the public and, over time, probably reduce the sense that there is likely to be public resistance to such works. In such an ideal world, orchestral management would not necessarily feel so wary of programming new works. They might see opportunities for engaging with the public in different ways. What if our workshop on Ulvo’s Concerto in August 2015 had been open to the public, for example, perhaps prefaced by a talk by the composer, soloists, and conductor?

I am realistic enough not to underestimate the magnitude of the attitudinal changes necessary to bring about such a transformation. However, I do believe that we should be ceaselessly looking for ways in which we can see the opportunities, rather than solely the risks, in making the music of today part of our contemporary concert-going experience.

Toolkit:

a) Be prepared for the fact that the processes involving brand new music rarely run according to plan, in purely practical terms. It is in the nature of contemporary music that not everything can be planned down to the smallest detail, and very often the deadline will be stretched for various reasons. Get used to evaluating whether the cause for the delay is because the composition needs a later deadline and a new performance date because it is incomplete or is yet to find its optimal form.

b) Find approaches or forums allowing you to attract the interest of more orchestral musicians, managements, and conductors early in the process so that more people develop a sense of ownership to the work at an early stage and can act as sponsors or supporters should the process threaten to derail. Look for ways of widening the pool of people engaged in the course of creating a new work. Can the orchestra’s base of regular concert attendees be brought into the process? With such an approach, might they take a different attitude to the work when it finally achieves its premiere slot in a concert?

c) Start a conversation about the need for trust among those involved in an entirely new works. Remember that fear undermines trust and therefore that understanding all the individual and collective anxieties accompanying the decision to go ahead with a work that, at the time of that decision, does not exist is paramount in anticipating the pressure points and mitigating them.

d) Show students that ‘new’ is not necessarily synonymous with ‘obscure.' Encourage them to see that a musical repertoire that excludes anything created less than a hundred years before their times is, by definition, incomplete and, arguably, contains the seeds of its irrelevance. Try to engage them in the excitement of making something new, the thrill of being a pioneer. Make them aware of their responsibility, as future professionals, to be evangelists for their art, to expand the musical horizons of their audiences, rather than just feeding them the familiar sounds they find comfortable.

© Ellen Kristine Ugelvik | go to top

The role of the soloist | Diamond Dust | Concert piece in three sections | Practische Beispiele | at the tips of my fingers | Woven Fingerprints | Theory of the Subject