Into the Hanging Gardens - A Pianist's Exploration of Arnold Schönberg's Opus 15

Return to Contents Bibliography

Introduction | The Score and My Role as a Performer | Learning Strategies | The Challenges of Schönberg's Musical Language | Playing Lieder by Arnold Schönberg - Contextualisation and Turning Point: "Grasping" Schönberg's Evolutionary Development | Musical Choices, Technical and Practical Considerations in Opus 15: Fingering and Hand Distribution | Pedalling | Dynamics and Colours | Polyphony and Voicing | Tempo and Tempo Modifications | Rhythm

“I have not discontinued composing in the same style and in the same way as at the very beginning.

The difference is only that I do it better now than before; it is more concentrated, more mature.”

(Arnold Schönberg)1

While I reflected on my relationship with the audience and drew inspiration from recordings, I started to prepare the second contextualisation of Opus 15. It seemed sensible to explore Schönberg’s musical language further after I had focussed on George’s poetry in the first concert. Therefore, I studied his songs Opus 2, Opus 14, Opus 48 and Am Strande and performed them together with Opus 15 in my second concert. Moore remarked that “[t]he work of the accompanist is one of the most varied in all music. […] Consider the variety in the style of playing and in the mental approach that is needed […] And we accompanists must be expert in and intimate with each.”2 Opus 15 is not part of the core repertoire which an accompanist frequently encounters in her career, probably because it requires a specific voice type and poses high demands on the performers. The new contextualisation, which out of all three had the strongest impact on my understanding of Opus 15, offered the possibility to explore the question if Schönberg’s music required me to “remake” myself as a pianist and accompanist and to investigate the “performative feel” of Schönberg’s Lieder.

In the following section, I elaborate first on both my artistic approach to the score and the practical strategies I employed to learn the “atonal” material of Opus 15. Special attention is then turned to the question if I need different skills or techniques as a pianist to play this repertoire. This question is explored in light of two settings of Karl Friedrich Henckell’s poem “Winterweihe”, which Richard Strauss set in 1900 and Arnold Schönberg in 1908, shortly before he started working on Opus 15. I then discuss how I perceived a notable shift in the way I heard and understood Opus 15 as a result of my second contextualisation of it, before I elaborate in detail on specific technical challenges Opus 15 poses for the pianist and discuss musical and practical considerations related to fingerings, pedalling, dynamics and colours, polyphony and voicing, tempo, tempo modifications and rhythm.

The Score and My Role as a Performer

My understanding of how I approach the score and what I do as a performer has changed throughout the project. Both my growing understanding of the nature of this project as artistic research, presentations and discussions at seminars and conferences of the Norwegian Artistic Research Programme and the dialogue with my colleagues at the University of Stavanger, particularly with the research group that focusses on performer’s knowledge,3 made me scrutinise the preconceptions I had about my role as a performer and my artistic goals. I got further inspired by literature on performance and artistic research, most notably Cook’s book Beyond the Score4 and Doğantan-Dack’s article on artistic research in classical music performance,5 which made me question the somewhat self-effacing role in which I had cast myself.

Prior to the project, I had a practicability-oriented, rather uncritical approach to scores that also determined the initial conception of the project, which was not fully focussed on the insights my unique perspective as an artist could provide. Katz describes collaborators as “fourfold custodians: We guard and maintain the composer’s wishes, the poet’s requirement as the composer saw them, our partner’s emotional and physical needs, and finally, of course, our own needs as well.”6 While I gave room for the three former in my approach, I hardly acknowledged the latter. My university-training had ingrained in me an attitude of “getting it right”, and my “accompanist-mentality” made me practice very goal-oriented as I was often driven by the need to reach a certain quality, a standard of execution and technique, in a short amount of time. Making it work was more important than finding my voice as an artist. At the same time, I was occupied with the idea of playing the words and developing an equal partnership between the singer and the pianist, as expressed in the project’s title “The Voice of the Piano”. As I elaborate in the next chapter, my understanding of collaboration got transformed as I realised to my surprise that my practice as an artist did not match my ideas of it.

My view of my role as a performer influenced how I began to interact with the score of Opus 15 and affected thus my emerging understanding of the music. In my initial reading, I tried to realise as much as possible of what is notated in the score, observed the notated pitches, rhythms and performance indications as closely as possible and learned both my part and the singer’s part. I had to make decisions on Schönberg’s “impossible” markings such as <> over a single chord, negotiate his verbal tempo indications with his metronome markings, and I also incorporated my view on the sound and emotional quality of the poetry, which I had previously analysed, into my reading. Gradually, my playing became more nuanced as I tried to determine the quality of each indication and Schönberg’s reason for writing it into the score. After having started with a close reading of the score itself informed by my understanding of the poetry, I tried to get to the meaning “behind” the score. I felt a strong ethical obligation to try to understand the composer’s intentions.

Besides my study of the poetry, I drew on Schönberg’s writings and literature on the performance practice of his school to inform my playing. However, I did not aim for an “authentic” or “historically accurate” performance. As Rosen points out, “[h]istorical purity is not the most important goal of a performance, particularly when we consider that we can never be sure that we are getting it right. The various aspects of music are too closely entwined: using the pedal as the composer intended is meaningless unless the phrasing, the dynamics and the acoustics are also correct, since the pedal will need to be altered if the phrasing is changed, the dynamics ill-interpreted, or the acoustics too dry.”7 Also, present-day audiences have different expectations and ways of listening than past listeners. Certain performance decisions one can hear in historical recordings seem no longer acceptable to our modern ears while other features have gained importance.

When I started to scrutinise my preconceptions about my role as a performer, I realised that most of what I do as a performer is not in the score and that my perspective and background as a pianist determines how I read the score8 and imagine the music to sound. It is not actually possible to know the composer’s intention. I have to “thicken the meaningful elements in the score to make a consistent interpretation [and in that process find] the balance between reliability and validity.”9 I negotiate the performance practices and traditions that are relevant to the work with the goal of giving the audience I play for new musical experiences. Being true to the music seems to mean being loyal to the forces behind the work as well as to how the current culture perceives these forces.

I asked myself: What can make my performance of Opus 15 more convincing? Through my study of recordings, I had realised that the most “perfect” performance was not the most interesting while those that had the most intriguing moments also had aspects with which I absolutely disagreed. I understood that, although one always continues to learn, this learning should not exclusively have the goal to “get it right” like it does when one starts to learn an instrument. This does not mean that I go deliberately against the score, but rather that I “make it mine”. Too much focus on tradition or technique and the ideal of “perfection” can be obstacles to imagination. On the other hand, creativity alone does not make a good performance either.

One of the challenges the performer encounters is the need to practise for the realisation of certain sound ideas. This practice, in turn, influences the performer’s perception of the music. The new understanding of my role made me question on a deeper level what I do and discover automatisms in my playing that I had not noticed before. The change in my awareness and focus influenced the development of my understanding of Opus 15 and led thus to new artistic decisions. It also helped me to articulate them in this reflection, in which I try to reveal the tacit knowledge rooted in my particular performer’s perspective that shaped the artistic results, rather than telling other performers how to play Opus 15.

Cook points out: “It is not obvious that there is a limit on the number, or nature, of viable performance options, whether these are informed by historical precedent, structural interpretation, rhetorical effect, or personal taste. In every instance there will be some reasons for doing it one way, and some for doing it another. Each will have its own consequences, which can be explored and evaluated. There are lots of ways of making sense of music as performance, and lots of senses there for the making.”10 Nevertheless, despite the new awareness of my role as a performer I have gained, I still feel that I cannot make a convincing performance by consciously going against what I perceive as the “correct way” of playing at that moment in time and in that particular context. Although I make decisions all the time, I do not see them as choices, as most of the time one of them appears to be the better solution to me. Although the demonstration of other choices might reveal new insights to an audience, they are unlikely as convincing as the one I “believe” in at that moment. Internalisation and thus to a certain degree automatisation is necessary to find conviction, and as Doğantan-Dack points out, “[c]onvincing artistic results cannot come from outwardly following certain learned rules and prescriptions alone, but requires being true to one’s own experiences and convictions.”11

I did not find Opus 15 particularly difficult to read or remember as I often have to learn music fast. Perhaps due to my “accompanist-mentality”, Opus 15 seemed to me just another score I had to “make work”. Although it contains complex parts that are technically or rhythmically challenging, at other places the textures are rather thin and thus easier to read. The often-occurring repeated patterns and motives make it not too difficult to notice reading mistakes, although it was challenging to know instinctively and hear where the music “is going” as the orientation aid harmony offers to the performer in tonal music is missing. Although the sound world seemed initially foreign, I quickly got a physical feel for Opus 15. I could transfer practice strategies I employed in other repertoire to my work on Opus 15 but had to adapt some of them to the difficulties related to “atonality”.

I “visually improved” the score: I made rhythmical relationships visible where the spacing of the score was confusing, marked coordination points with the singer and indicated reference points in the piano from which the singer could pitch her notes. I carefully read the score and marked performance indications that were difficult to discover as they were written on top of the voice part.

To gain an understanding of the polyrhythms, I sketched them in relation to their lowest common multiple and practised clapping and playing them according to these subdivisions. I also tried to get a feeling for the connection within each rhythmical voice by practising them with the metronome and alternating the rhythms instead of playing them simultaneously.

I found it very important to know the singer’s part before our first rehearsal. With tonal repertoire, I usually sing along from the early stages of learning, but in Opus 15, I found it difficult to read the voice part and my own part simultaneously and to find the correct pitches. Therefore, I recorded a metronomic reading of the singer’s part, often at a slower tempo than the one indicated, so I could play along and get a feeling for the pitches and coordination. I also spoke the text while playing my part to free myself from the stiff pulse of the metronome. Gradually, I started to sing along, first with the recording and then without it. As I still had trouble pitching some places correctly, I often turned back to speaking. My singing gave me insights into possible pitching challenges and allowed me to gain an idea of how the singer might breathe and which tempi might be suitable for certain phrases. Although this preparation work was valuable, the first rehearsal experience was still confusing at parts as I had to integrate an external impulse that was much more complex than my metronome recording into my playing. When I sang and played on my own, I actively shaped the music, whereas I had to be both receptive and active when I played with the singer. In the early rehearsals with both singers, I was also preoccupied with intonation. Although it is the singer’s task to regulate intonation, I paid close attention to it because, as I describe in the section on collaboration, I was used to coaching singers, and I felt a huge responsibility for the artistic outcome as this was my project. Listening to intonation is also closely related to perceiving and reacting to the singer’s colours. Particularly before the first concert, this took a lot of concentration as I had to listen to it consciously because I had not yet developed an instinct for it despite my practice of singing the voice part. It was difficult for me to distinguish pitching from colour. Having checked that the pitching was indeed correct, I used my recordings of the rehearsals with the singer to become accustomed to the pitches and her voice colour.

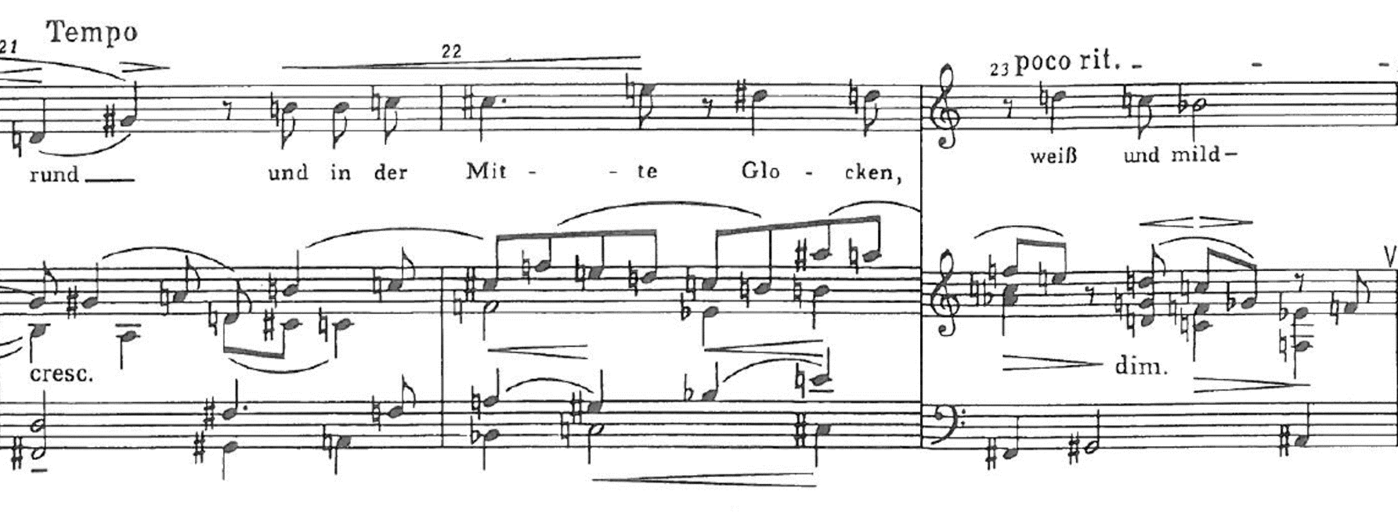

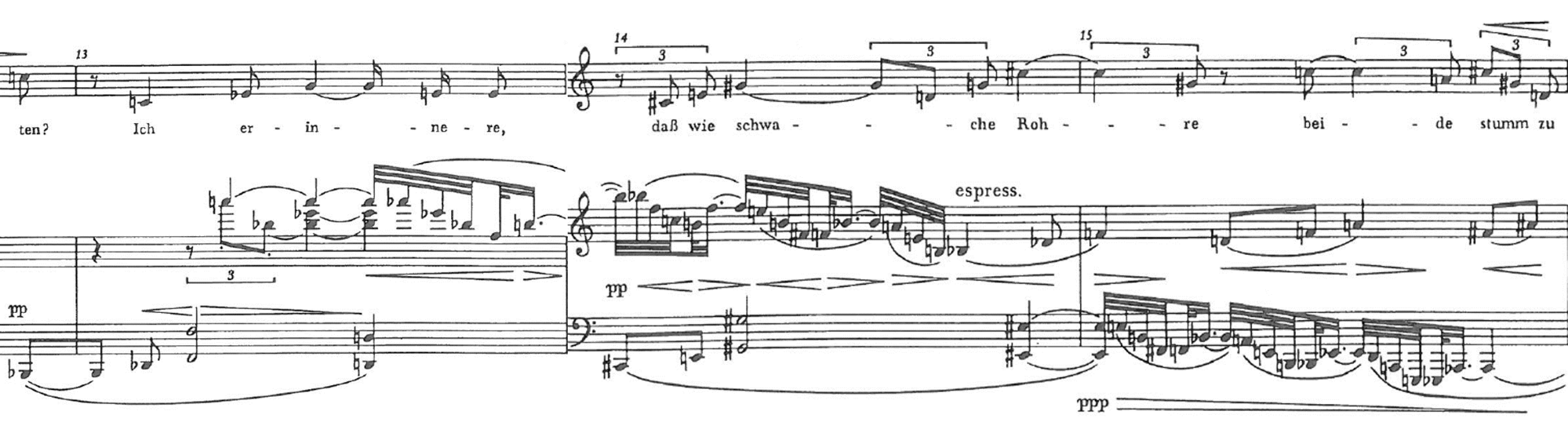

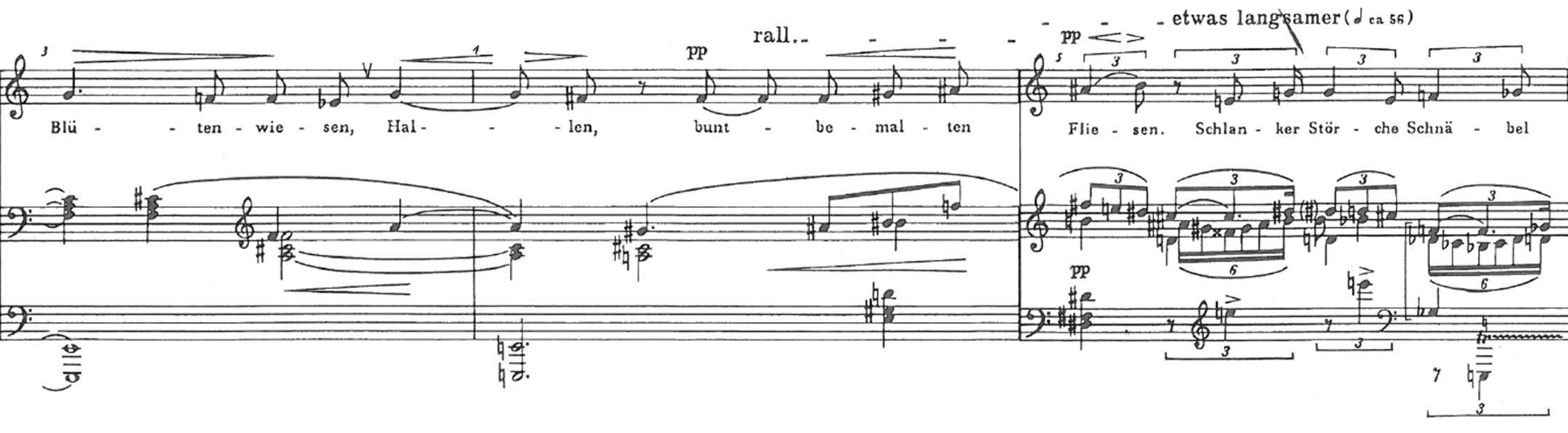

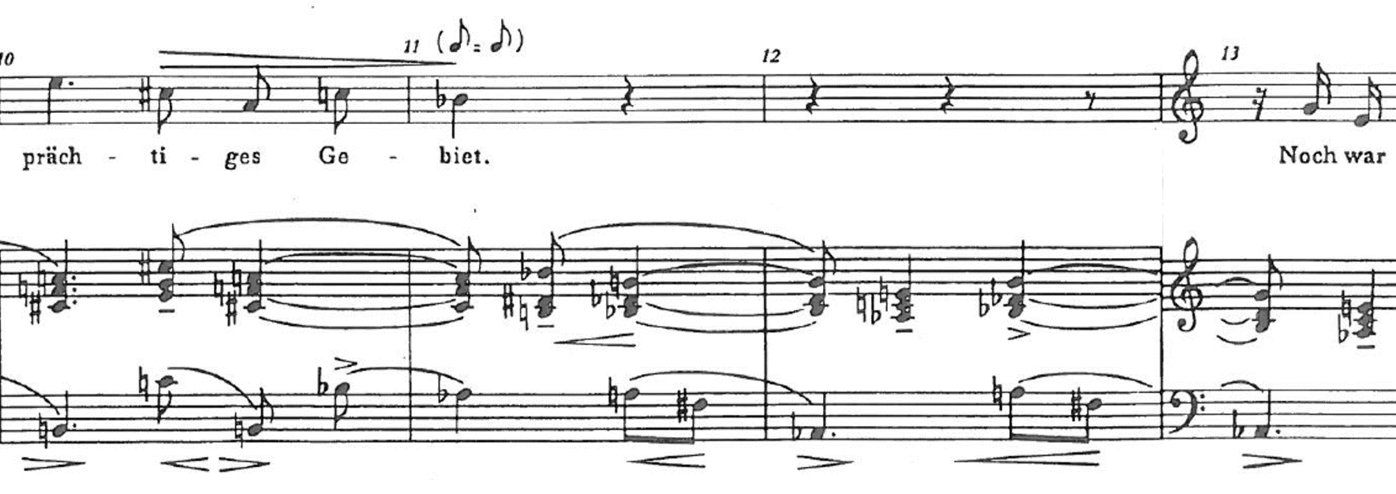

Another strategy I employed, sometimes unconsciously, was to hum along with my own voices as it helped me to feel a connection in the larger intervals that my fingers cannot connect. I also sang along consciously to develop an organic way of phrasing and breathing. I employed this strategy in particular after the first concert when I started to realise that I shaped my phrases too much according to the singer’s part. Later, I also discovered that I even needed a different sense of gravity in my two hands occasionally and found it helpful to practise and sing polyphonic voices individually. Playing at various tempi helped me to feel longer connections in parts that are usually slow and to listen to and bring out details, for example of dynamics and articulation, in faster places. Deconstruction was also a useful strategy in the early work with the singers, for example, to achieve synchronisation in the eighth song.

Kerrigan wrote in her rehearsal diary of Opus 15 about her prioritisations in the learning process: “In singing other music, the quality of the voice is constantly being evaluated to produce the most beautiful sound possible. This music requires a different order of priorities, first the pitching and rhythm, then the beauty.”12 Although I also started with a “technical” reading of the score, which turned out to have a bigger impact on my phrasing and flexibility than I thought, I shaped and coloured the music immediately out of what I found aesthetically pleasing. As I discuss in the section on polyphony and voicing further down, my ideal of tonal beauty impeded the development of a more nuanced voicing and contributed to a rather flat way of playing, in which I tried to smoothen over the edges rather than bringing them out as something interesting. Nevertheless, I was aware of the difficulty to give each song its distinctive character from early on, particularly since much of the music is kept in rather soft dynamics and slow tempi. Although the text helped me to find and bring out certain qualities in the music since the beginning of my work on Opus 15, only later I realised that I had to listen more closely instead of mainly “reading” and “thinking” to be able to connect the metaphorical associations I created to the sound. While the above-described learning strategies helped me to “make it work” quickly in most aspects, I could create a more artistically convincing performance only through internalisation and experience. As I describe further down, the development of a “real” understanding of the sounds of Opus 15 was closely related to my second contextualisation as it allowed me to hear and feel the connection between Opus 15 and Schönberg’s earlier Lieder that are more easily accessible to the ear.

The Challenges of Schönberg's Musical Language

One of the questions I wanted to find answers to in my project is if I need different skills, techniques or competencies to play Opus 15 as opposed to earlier repertoire and if Schönberg’s musical language requires me to “remake myself” as an accompanist.

Opus 15 is often considered to be the starting point of Schönberg’s so-called atonal period.13 Jan Maegaard argued that Opus 15 was Schönberg’s first completed, entirely atonal work that he presented to the public.14 In the program for the premiere of Opus 15, a private performance in Vienna in January 1910, Schönberg himself wrote: “With the George-Lieder I have succeeded for the first time in approaching an expressive and formal ideal which has haunted me for years. […] now that I have started definitively upon this road I am aware that I have burst the bonds of a bygone aesthetic”.15

No settings of texts from Opus 15 by other major composers exist. There is, however, another setting of Schönberg’s “In diesen Wintertagen”, Opus 14. Richard Strauss composed “Winterweihe”, as the poem is originally called, in 1900. His setting was published in 1904 as Opus 48 No. 4, and according to Pfeiffer, it might have inspired Schönberg to set the text himself, as the poem, unlike many by Richard Dehmel and Stefan George, could not be found among the texts in Schönberg’s library.16 Schönberg composed his two songs Opus 14 in the winter of 1907 and 1908. The sketch to “In diesen Wintertagen” is dated 2nd February 1908, whereas the first sketches of songs from Opus 15 are from March 1908.17 Although both songs of Opus 14 still have triadic closures, and thus have not quite reached Schönberg’s “new expressive ideal”, they have aspects of musical language in common with Opus 15, for example, quartal harmonies or the importance of motivic context for the content of chords. Schönberg himself attested to the relatedness of the compositions when he in 1949 wrote in My Evolution: “This first step occurred in the Two Songs, Op. 14, and thereafter in the Fifteen Songs of the Hanging Gardens and in the Three Piano Pieces, Op. 11. Most critics of this new style failed to investigate how far the ancient ‘eternal’ laws of musical aesthetics were observed, spurned, or merely adjusted to changed circumstances. Such superficiality brought about accusations of anarchy and revolution, whereas, on the contrary, this music was distinctly a product of evolution, and no more revolutionary than any other development in the history of music.”18 Here, we read not only about the relatedness of the two opuses, but also Schönberg’s often repeated claim that he continued in the tradition rather than rupturing the progress of Western art music.

Because of the similarities between Opuses 14 and 15, I thought a comparison of my approach as a pianist to the two “Winterweihe” settings – one tonal, one on the verge of atonality – might help me come closer to answering my question. I presented the two songs and my views on them in a lecture-recital in 2016.

Video example 1: Richard Strauss: “Winterweihe”, Op. 48 No. 4. Lecture-recital excerpt, with Felicia Kaijser – soprano, 13.09.2016, Lille konsertsal Bjergsted, Stavanger.

Video example 2: Arnold Schönberg: “In diesen Wintertagen”, Op. 14 No. 2. Lecture-recital excerpt, with Felicia Kaijser – soprano, 13.09.2016, Lille konsertsal Bjergsted, Stavanger.

Many skills are involved in the accompaniment of German Lieder, though during a performance, I do not think about them consciously. Instead, I rely on previous experiences and training, the knowledge what works and how I should adjust small nuances to make it work. Understanding the implications of the text on all its levels and being sensitive to how it “translates into”, interacts with and is transcended by the music is one skill that influences what I hear, think and feel when performing Lieder. As I did with all the repertoire of the project, I approached Schönberg’s and Strauss’ setting through the text. An analysis of the poem can be found in Appendix A. As the text is the same, I assumed at first that whatever the words guide me to do as a pianist should be similar in both songs, at least it should be within the normal sphere of differences that I am familiar with from my previous work. That means even if one composer goes with the natural way of speaking and the other against it, or if one highlights different aspects of the poem than the other, the text itself should not provide any challenges or require new skills, just because it was Schönberg who set it. However, Schönberg’s text changes necessitated some decisions from us performers as I explained in the lecture-recital:

Video example 3: Lecture-recital excerpt, with Felicia Kaijser – soprano, 13.09.2016, Lille konsertsal Bjergsted, Stavanger

|

Strauss: Op. 48, No. 4, “Winterweihe” |

Schönberg: Op. 14, No. 2, “In diesen Wintertagen” |

|

In diesen Wintertagen, Was milde Glut entzündet, Wir greifen kaum hinein, Dem Schein der Welt verschollen, Auf unserm Eiland wollen Wir Tag und Nacht der sel‘gen Liebe weihn. |

In diesen Wintertagen,

Nun sich das Licht verhüllt, Was wilde Glut entzündet, Wir greifen kaum hinein, Dem Schein der Welt verschollen, Auf unserm Eiland wollen Wir Tag und Nacht der seligen Liebe weih'n. |

Table 1: Comparison of Strauss' and Schönberg's changes of the original poem text

Having studied the text, I had a closer look at the music of the two songs. A first sight-reading comparison revealed no immediately apparent new skills I would need as a pianist in either song. I did not have to practise them for a long time just to gain fluency and a feeling for the overall form. The sight-reading revealed already that both songs follow the poem’s division into three parts in their ABA forms.

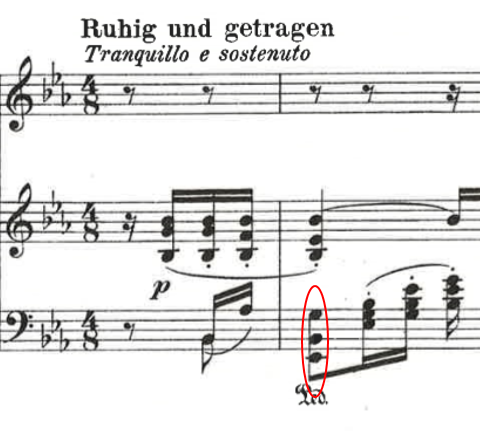

The most obvious technical difficulty in Strauss’ s setting is the left-hand chord of bar 1 that is repeated and transposed throughout the song, and that is too wide to play simultaneously with my small hand.

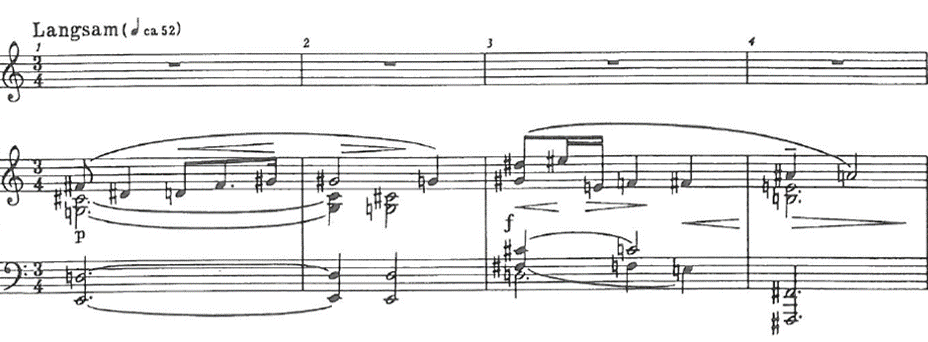

Figure 1: Richard Strauss: “Winterweihe”, Op. 48, No. 4, bar 1

There are a few stumbling blocks in Schönberg’s setting when the texture gets tighter, like in the excerpt I demonstrated in the lecture-recital (video example 3), but overall the song is rather easy to sight-read. I did not have to practise the piece for a long time to gain fluency and a feeling for the overall form, which like in Strauss’s setting follows the poem’s division into three parts in an ABA-form.

When I started practising Strauss’ setting, it seemed slightly uninteresting to me despite its beauty. The piano part is not independent but follows the vocal line, whose notes it doubles at the beginning of each stanza. The rhythmical pattern of an eighth note followed by two sixteenth notes and two eighth notes in each bar is very repetitive with only minor variations and filling out, most notably when the central motive of the descending third (g-f-e flat) in its rhythmical form of three sixteenth notes before a downbeat occurs. The song’s repetitiveness conveys to me the calmness and gentleness expressed in the poem but can make it difficult to get a feeling for the bigger phrases and can easily get uninteresting. I was therefore very aware of the small rhythmical variations the song offered. A triplet appears for the first time in bar 13 under “fort und fort” (“on and on”), underlining the speaker’s urgent wish that the glow of their love will burn forever. Another rhythmically prominent place is in bar 29 to the words “Tag und Nacht” (“day and night”), where the repetitive motion suddenly stops and turns into much slower quarter notes and half note which underline the lovers’ undisturbedness by the passage of time.

Figure 2: Richard Strauss: “Winterweihe”, Op. 48, No. 4, bars 13 and 28-30

Harmonically, Strauss’s setting is very conservative compared to Schönberg’s. The first stanza is almost entirely set in E flat major, which is clearly confirmed by the pedal point E flat at the beginning of each of the first five bars that adds to the impression of calmness and gentleness. In the second stanza, the chromatic mediant B major on “Geisterbrücken” (the spiritual bridges) is most striking. At this point, the rising chords in the piano that appear throughout the whole song, rise even more, up into the fourth octave and connect thus the “worldly” low register with the “spiritual” high register.

The whole song has few performance indications, most of them related to the soft dynamics (p and pp), the calm tempo and the small-scale phrasing that is indicated by bows. When I practised playing and singing along, I discovered that the repetitive piano accompaniment gets more interesting together with the vocal line with its long lines. Following the vocal line and the text makes it easier to give meaning to the repetitive harmonies, and to bring out unusual chords. For me, the primary challenge with this song was to keep going instead of “ending” every time we reached the tonic and not to make it more complicated than it is.

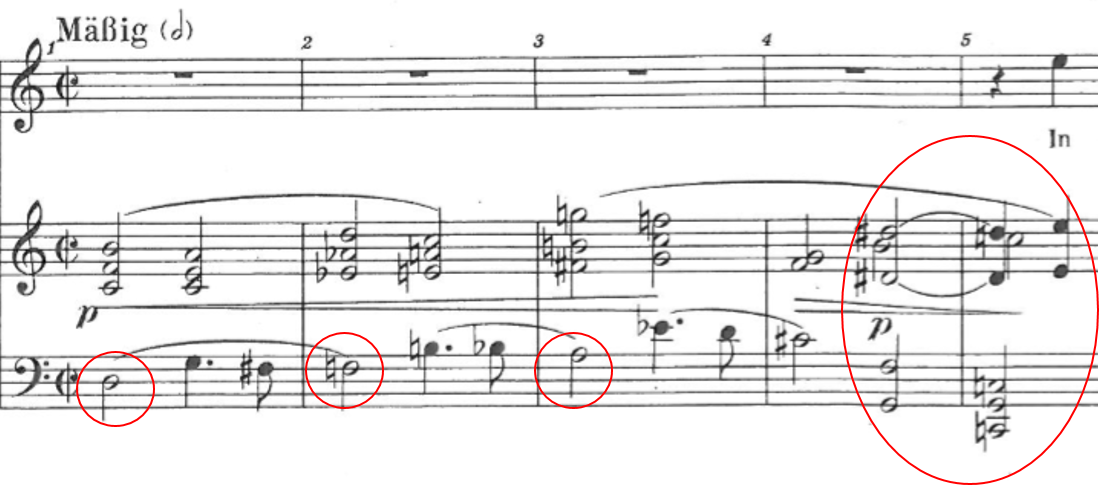

When I started working on Schönberg’s setting, I was surprised at how traditional it seemed compared to the first song of the Opus. Like in Op. 14, No. 1, almost every verse has a corresponding phrase in the music. Rests in the vocal part, rhythmical relaxation and motivic structures highlight the beginnings and ends of these phrases. Unlike in Op. 14, No. 1, in this song even root position triads appear throughout the work, and the piano introduction ends with an authentic cadence in C major. As Haimo points out, Schönberg prepares it by giving the diatonic tones of C major a privileged status: all of them are used in the first two chords while all the other, foreign notes are less important and always lead to diatonic tones by half-steps.19 Cinnamon describes it as a ii-V-I cadence with the d minor being underlined by the bass arpeggiation d-f-a.20 Unlike Strauss, who confirms the tonality with the pedal point, Schönberg keeps the C major chord only for a short moment, immediately going on to other harmonies. The referential function of C major gets however confirmed by the repetition of the opening material that comes five times again throughout the song. Even though it does not lead to C major cadence in all cases, it is repeated at the same pitch level.

Although I can hear the tension of the opening cadence, it did not work for me to try to emphasise “tonal” triads. Like in tonal music it is not possible to “spell out” each harmony without losing the flow and the overall structure of the piece. Similar to the Strauss song, the challenge for me as a performer was not to let the cadence feel like an ending. It is just the piano introduction that prepares for the singer’s entrance.

Figure 3: Arnold Schönberg: “In diesen Wintertagen”, Op. 14, No. 2, bars 1-5

Motives play a significant role in Schönberg’s song. There are different ways of describing them,21 but no matter where one puts motivic borders, it is evident that these motives are related and that they pervade the whole song. Few tones are not somehow determined by them. Being aware of them is important for me as a performer, as my understanding of them is a part of what determines my phrasing. Of course, Schönberg was also very exact in his way of notating the music and gave clear indications of phrasing, articulation and dynamics.

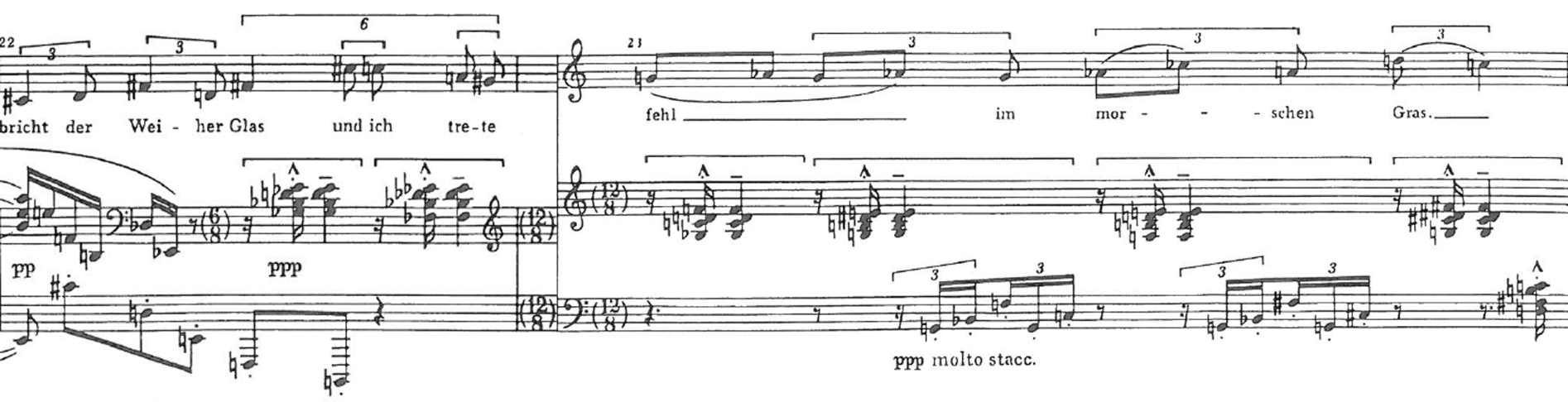

Figure 4: Arnold Schönberg: “In diesen Wintertagen”, Op. 14, No. 2, motivic analysis22 (excerpt) bars 1-11

The biggest challenge as a performer was perhaps to become familiar with another chordal vocabulary, to chords that sounded and felt different. I had to “make them mine”, also to understand how the singer’s and my voice fit together and to be able to advise on intonation in the rehearsals. Other elements than harmony like rhythm, motives, texture, register, dynamic and tempo markings helped me understand the piece when my ears were not quite used to how tension and repose work in this extended chordal language.

Even though a performer is perhaps the best person to ask what skills or techniques a certain piece or a particular style requires, it remains a difficult question to answer. As a performer, I do much subconsciously and take in a lot of information from different sources that determine how I interact with a new piece. For example, I had played more music by Schönberg than by Strauss during the year before I made this comparison. Therefore, it almost felt like I had to “remake myself” when playing Strauss. Only in the absence of something, when something does not quite work, I might notice that I need a new, special skill. The question, if I need different skills to play music on the verge of atonality is also difficult to answer just from the comparison of two songs. Each piece requires slightly different skills, techniques, ways of thinking and understanding the music from the performer. When I worked on this comparison in 2016, I concluded that my approach to these two settings is different. However, so would it be if I played songs by Mahler, Reger or Pfitzner, or even a second setting by Schönberg or Strauss. As a classical musician, and as a collaborative pianist in particular, who often is faced with many different works in a short amount of time, I have to be able to get under the surface of a composition, to learn its “dialect” of sound, understand each element within its context to create a performance that is meaningful for today’s audience. I have to be familiar with so many different styles and ways of playing that I believed Schönberg’s extension of tonality to be just one of them. One might perhaps have to put in slightly more effort into getting familiar with the harmonic language if one is not used to it, and other musical parameters than harmony become more important. However, as far as I could answer the question from just these two songs, I did not think I had to remake myself as an accompanist to play music on the verge of atonality. Like all music, it required understanding and familiarity from me. Perhaps my previous training made me able to understand “tonal” music more instinctively, whereas I worked on this repertoire more consciously. This conscious way of working is something I take with me to my future artistic projects. I concluded I did not have to “remake myself” to play this music, yet this music, like all music, “remade me”.

Looking back to this comparison at the end of my project, I wonder if the way I went about answering my question still makes complete sense. The result of my little experiment seems self-evident: I shape each piece of music differently, and each piece of music shapes me as a performer. Although I discovered that I indeed seemed to focus on different musical elements and that I let myself be guided to a greater extent by other musical parameters than harmony in Schönberg’s setting, my view on the problem seems to have been somewhat one-sided. I tried to dissect my approach to these songs by studying how I deal with specific musical features and seem to have forgotten that everything I do happens in a context that encompasses more than just the relationship between the piece of music and myself.

Listening to the recording of the lecture-recital, I notice that I seem to lead more in Schönberg’s Lied. The reasons for that might not lie solely in the music. The singer’s attitude heavily influenced my playing. I knew she was more comfortable with Schönberg than with Strauss and therefore felt I had to give her more space and let her decide on tempo and tempo modifications in Strauss’ song. Also, as this was my project about Schönberg, I might have been more dominant in the negotiation with the singer in Schönberg’s song. Finally, the performance situation itself might have had an impact on my playing that I did not consider. While detailed thoughts on musical parameters were important in the preparatory work alone and with the singer and provided me with a kind of knowledge depository for the performance, my focus is different during the actual performance, which in this case was a presentation of this comparison.

Playing Lieder by Arnold Schönberg – Contextualisation II and Turning Point:

“Grasping” Schönberg’s Evolutionary Development

My supervisor asked me if I was influenced by the Strauss setting when I played Schönberg’s Opus 14 for him because I seemed to feel it in a late-Romantic fashion. As I learned the Strauss song later, I do not believe I was very much influenced by it, although it might have had some impact of which I am not aware. My study of Schönberg’s earlier Lied compositions, on the other hand, informed my playing of Opus 14 considerably, as I could see, hear and feel many similarities despite the more radical tonal language. Back then, I did not think I needed truly new skills to play “atonal” music, but looking at it with some distance, I believe that I would not have been able to play the work the way I did had I not developed this understanding of Schönberg’s musical language through my performance of his earlier works, which also affected my understanding of Opus 15.

It is not easy to describe and pinpoint exactly how the contextualisation influenced my changed view on Opus 15 because the change happened primarily in my embodied perception rather than my analytical understanding. It is the way I “grasp” the music through my hands and ears that has changed and that I associate with the feeling of Opus 15 being less foreign and more “mine”. I seemed to have discovered for myself in a pianistic way that Schönberg might have been at least partly right in his claim that he continued to compose in the same style and manner as before.23

I noticed that a transformation of my hearing had taken place while I practised Opus 2 and Opus 15 in quick succession. Although I had known parts of Opus 2 before, it was through this direct contact that I started to hear and feel Opus 15 differently. Particularly the chordal texture at the beginning of the second song of Opus 2 that is homophonic with polyphonic details disclosed to me a way of listening by paying attention to the “horizontal” and “vertical” connections of the music simultaneously. In my early playing of Opus 15, I often emphasised the upper voice in a chord at the expense of the complete harmony.

The beginning of the second song of Opus 2 is highly chromatic and contains many seventh chords and few triads. Although the tonality of F sharp minor is established through the first chord, Schönberg immediately moves away from it and reaches F sharp major first in the sixth bar. He closes the phrase with an authentic cadence, but his harmonic progressions until then are more unconventional.

Figure 5: Arnold Schönberg: Schenk mir deinen goldenen Kamm (Jesus bettelt), Op. 2, No. 2, bars 1-6

Schönberg’s tendency of evading triads contributed to my perception of connections to Opus 15. Already in Opus 2, a chord that is usually felt as dissonant can be associated with a resting point: In bar 38, which is marked “zurückhalten” (hold back, slow down), an augmented triad occurs at the end of a diminuendo from pianissimo. The chord has still a certain tension and gives weight to the following rest, but seems to lose part of its dissonant feel in this context.

Figure 6: Arnold Schönberg: Schenk mir deinen goldenen Kamm (Jesus bettelt), Op. 2, No. 2, bars 36-39

My understanding of Opus 2 had an impact on how I perceived the chordal textures in Opus 15, particularly in homophonic endings and in the entire fifth song, which due to its homophonic structure and the cadential feel of the end seemed most closely related to this song from Opus 2 although the chordal vocabulary itself differs. My aural association of the two songs, which might have been influenced by the emotional quality of the poetry as both texts express a passionate plea, also contributed to a shift in how I perceived the fifth song of Opus 15 physically. Initially, the quartal chords felt slightly tense and unnatural to the hand which might have contributed to my problems of balancing them well. The seventh chords in the second song of Opus 2 are mostly distributed in such a way between the hands that, particularly in the right hand, octaves divided into a fourth and a fifth with the fourth on top often alternate with similar structures that have the fifth on top. In bar 5, for a brief moment, the right hand even contains a chord that consists of an augmented fourth and a perfect fourth on top of each other. After I had practised this song with a focus on voicing, voice-leading and tension within the hand, I could suddenly “grasp” the quartal chords of Opus 15 that now felt much more natural.

Besides my study of recordings, both those made by other performers and my own from the first concert, my new way of listening derived from Opus 2 also contributed to my changed perception of the more polyphonic textures of Opus 15. I seemed to be able to hear both the melodic progressions and harmonic simultaneities more clearly, and I searched for more flexibility in the phrasing of each voice. This search for flexibility was not put externally onto the music due to the wish to play more communicatively for an audience, as was at least partly the case in my experiment with “Kjærlighetsbrev”, but a result of my changed perception of the music. I found it difficult to share this search for flexibility with my first singer, although she was very accommodating to my suggestions and although she took part in both contextualisations, albeit not by singing the whole concert. As this was my project, she seemed to be less immersed in it and more occupied with “making it work” rather than searching for new expressions together with me. We nevertheless achieved a greater flexibility and expressivity in the second concert, but I looked forward to the collaboration with a new singer when I found out that she could not sing the third concert with me due to other commitments. While I benefitted from the thorough work we did together, I hoped that a fresh start in a new collaboration would give me further musical impulses and allow me to negotiate Opus 15 anew in a more flexible way. Although other factors played into my evolving understanding, like the amount of time I spent studying Opus 15, the gained energy and mental capacity after the first performance, my reflections on reception and the inspiration I drew from the recordings, I perceive the impact the second contextualisation had on my playing as one of the major turning points of the project.

I believe that my search for greater flexibility, which was prompted both by my study of recordings and by a different way of hearing polyphony and emphasised by the perception of being slightly stuck in a certain way of shaping tempo modifications with my first singer, ultimately led to a more gestural style of playing. In 1912, a critic wrote after the first public performance of Opus 15 in Berlin: “One must completely divorce oneself from the definition of a Lied in these twelve [sic] pieces. It is a sung declamation to which the piano now and then throws in a few single sounds, or suddenly without apparent reason a flashing figure, a raging, passionate outbreak of a few seconds. [..] The role of the accompanying piano is incomprehensible to me.”24 He did not see the quality of these figures and outbreaks, which I gradually started to perceive as gestures.

Musical Choices, Technical and Practical Considerations in Opus 15

The following section deals with craft-related aspects of my performance preparations of Opus 15, the technical challenges I experienced and practical considerations I made. When I started my project, I considered creating a “performer’s score” to show both my artistic choices and practical solutions, but I decided against it because no notation can capture all the nuances of the quasi-improvisatory flexibility that is essential for making a performance live and breathe.

Although what is perceived as technically challenging is closely connected to the performer’s musical goal and differs as each performer has a different body, my considerations and practical solutions might inspire other pianists to try them out and might make singers aware of potential difficulties in the ensemble. Particularly during the early rehearsal stages, technical difficulties might diminish the pianist’s ability to listen and react to the ensemble. Although ideally, both performers are well prepared, the rehearsal immediately changes the way I play, and what had previously worked well enough alone can be challenging again in the ensemble when suddenly basic parameters, particularly intonation (for the singer) and rhythmical coordination, need considerable attention.

Unless I just became aware of a minor problem and found a solution to it shortly before the performance, I did not consciously think about technical challenges during the concerts. Nevertheless, my practical decisions had a significant impact on how the performances sounded. While the automatisms I create through my decisions, both conscious and unconscious, in the practice room are necessary to be able to play at all, each technical solution potentially limits the way I feel and thus hear the music. As flexibility became one of the most important qualities I strived for in my later performances, I realised I had to scrutinise automatisms in my playing on all levels including my practical choices and prioritisations. Some of my early decisions of the first learning stage turned out to last, whereas I reconsidered others when my views on the music changed or I found a more “convenient” solution. This is a process which is not finished after one performance, so the following reflections can only be considered intermediate. Like my reflections on the poetry, they are not limited to the thoughts I had at the time I contextualised Opus 15 with other music by Schönberg, but developed throughout the project and contributed to how I performed Opus 15 in the final concert.

Fingering and Hand Distribution

Many performers stress the importance of finding good fingerings. According to Neuhaus, a pianist’s chosen fingering should first and foremost serve the musical idea. He wrote: “[…] that fingering is the best which allows the most accurate rendering of the music in question and which corresponds most closely to its meaning. That fingering will also be the most beautiful. By this I mean, that the principle of physical comfort, of the convenience of a particular hand is secondary and subordinate to the first, the main principle. The first principle considers only the convenience, the “arrangement” of the musical meaning which at times not only does not coincide with the physical convenience of the fingers, but may even be contrary to it.”25 Neuhaus also emphasised the “understanding and sensation of individuality (of its own peculiarities) of each of the fingers”26 as a guide for appropriate fingering. For a collaborative pianist, fingering can depend on the context. For sight-reading tasks or work with little preparation time, physical comfort and easily memorisable patterns might be more important than finding the most beautiful fingering. Perhaps Adler had this kind of work in mind when he wrote “It is not always the traditional way of fingering that the accompanist will employ: each will have some weak fingers, usually the fourth and fifth. The piano virtuoso cannot afford such a weakness. Unless he overcomes it, he will never reach the top. But the accompanist can still be outstanding in his metier, even if he does not do exercises for eight hours a day to strengthen his weak fingers.”27 In a Lied performance, however, I believe that considerations about fingerings are similar to those in solo performances with one aspect that is of particular importance: flexibility. As Katz remarked, “[i]t is also of paramount importance that the pianist have no physical impediment; an awkward fingering or the slightest bit of tension with a hand position change can limit flexibility ever so slightly, and this limitation can cost us the freedom to be as natural as our partner is”.28

Fingerings can have a tremendous impact on a pianist’s sound as they affect articulation, timing and colour. Although it is possible to “fake” the effect of a certain fingering through close listening, fingerings often limit the possibilities of shaping the music. Sometimes, I might choose a practical fingering early in the learning process without being conscious about creating automatisms in my playing. To find new ways of playing, I might have to consider new fingerings as well.

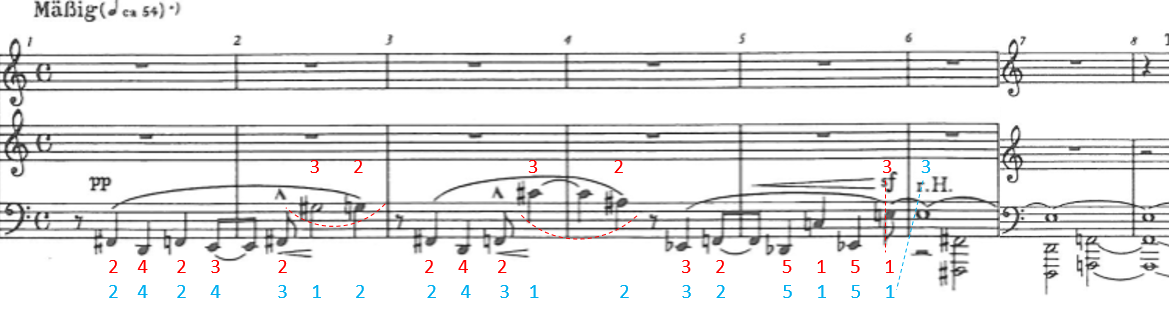

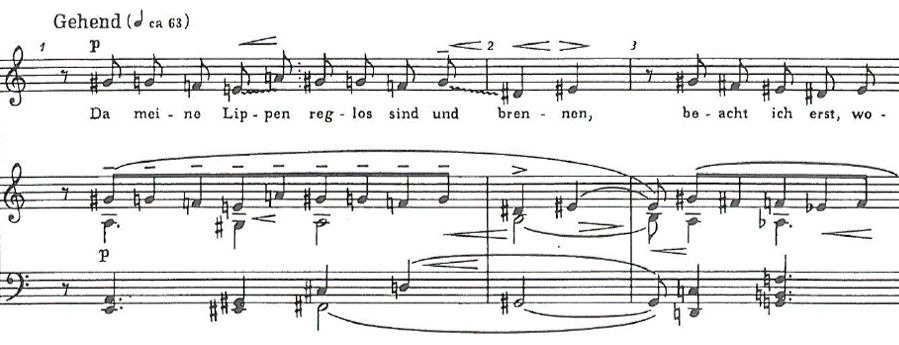

One place I kept returning to repeatedly in my study of Opus 15 was the introduction of the first song. As it opens the entire cycle, its shaping was particularly important to me. Katz wrote, “[w]e have the task of making the singer’s first words inevitable and necessary, as well as depicting the feelings that engender them.”29 When I started learning the music, I quickly noticed that I could barely connect the leap in bar 2 and not at all the leap in bar 3. I tried to distribute the notes between the left hand and the right hand but was not satisfied with the difference in sound. Consequently, I played the first five bars with the left hand alone. I tried to connect the leaps with pedal, but the vibrating of the strings disturbed the clear sound I wanted to create and interrupted the tension that I had built up in the previous syncopations. Therefore, it made the most sense to me to separate the martellato from the following note, and I considered the small crescendo, which is impossible to realise on the piano anyway, as a kind of gravitational momentum. The blue writing in the following score example indicates the fingering I used in the first concert. I was not entirely satisfied with this solution, as I sensed the separation of the notes disturbed the gestures. The tension I created in the syncopations and the leap still did not match. Inspired by Aribert Reimann’s first recording, I reconsidered the distribution of the hands and found that I could match the sound of the two hands by imagining the physical sensation of a one-handed leap and thus imitating the timing of the gravitational momentum. The red writing indicates the fingering I have used since the second concert. I still start the introduction with the fingering 2 4 2 to physically feel the tension between the major and the minor third. Playing the right-hand parts with the third and second finger feels much more natural for conveying the sighing ending of each gesture than my previous left-hand fingering did.

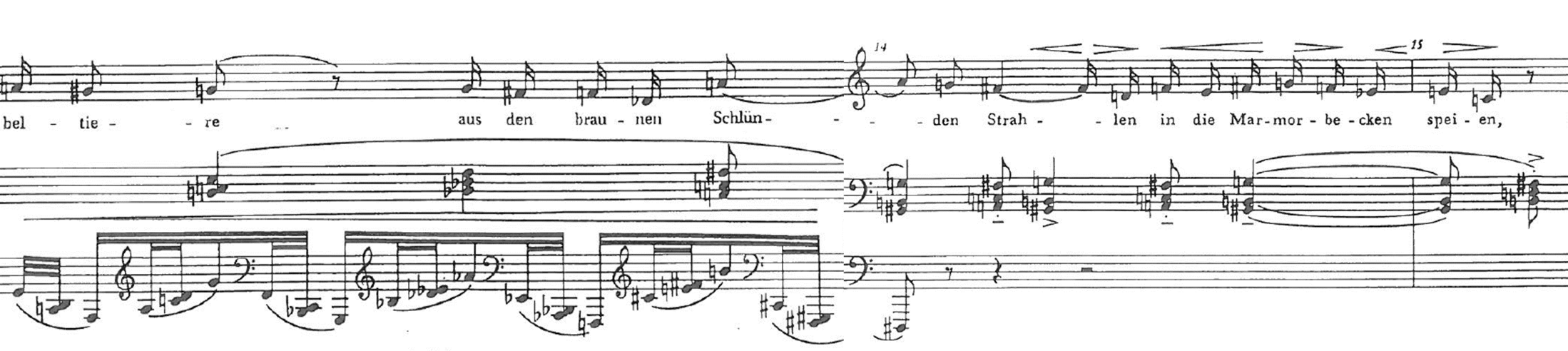

Figure 7: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. I, bars 1-8, fingerings

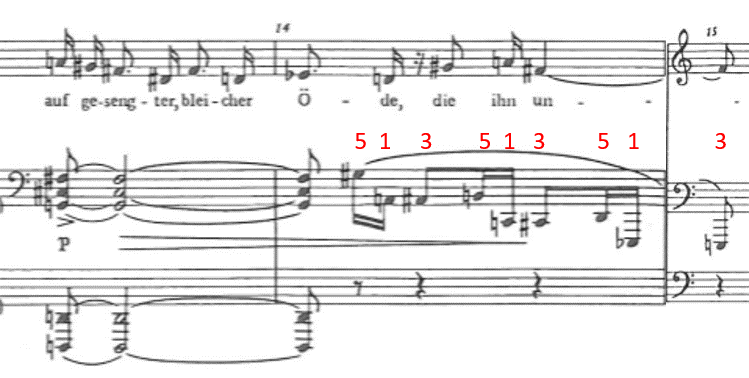

In bar 12 of the same song, a mark indicates to start a passage of fleeting thirty-second notes with the left hand. Several fingerings seem possible, among them a distribution of each figure into another hand (in blue writing in the following score example). I decided, however, to ignore the marking and to start with the right hand (as indicated in red writing). While my fingering is slightly less comfortable, I can still observe the accents and articulation, and it allows me to feel the connection to the right-hand d and to hold the left-hand chord as long as possible without obscuring the small figures with pedal.

Figure 8: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. I, bars 12-13, fingerings

I decided to play the end of the second song with the left hand, not because the place is technically challenging or because the redistribution would allow me to hold a chord longer, but to bring out the longing tenuto sound, which seems to “fit better” into the left hand. I got inspired to try the redistribution by a marking in Schönberg’s first fair copy, which must have been used by a pianist as the fingerings and written note names indicate.30

Figure 9: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. II, bars 11-14, hand distribution

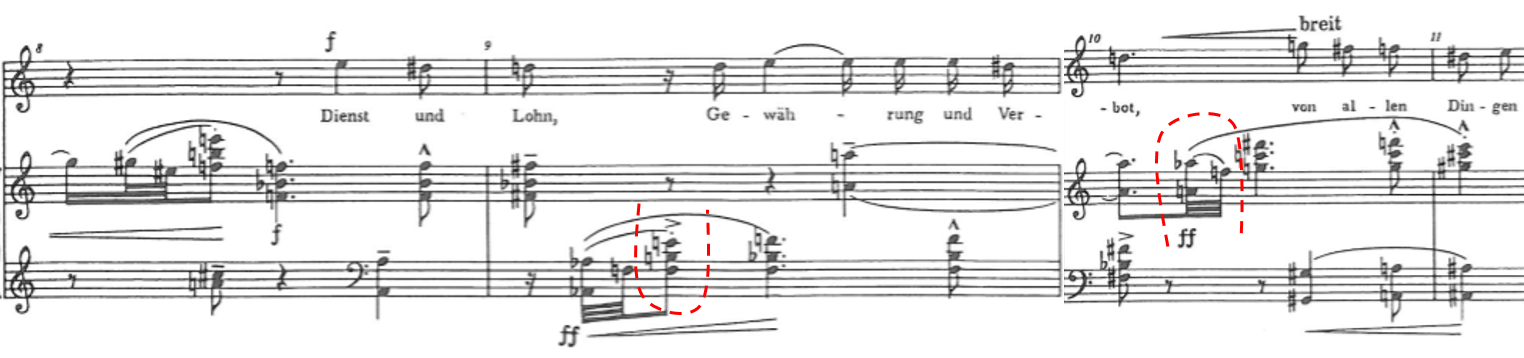

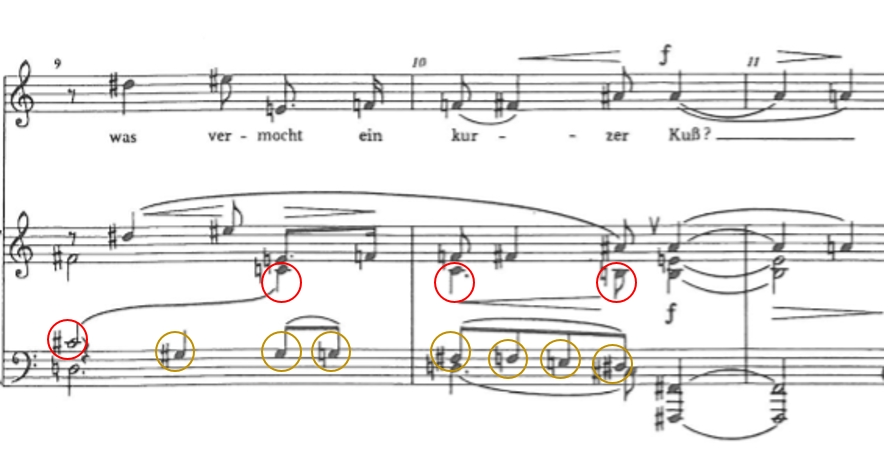

In bars 9 and 10 of the sixth song, I redistributed the parts so that I could play very rhythmically with clear articulation and a full sound undisturbed by the leaps. It is important to hear the different voices despite the changed distribution. Practising each staff separately or singing along with one of them while playing both helped me to work out the polyphony.

Figure 10: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. VI, bars 8-11, hand distribution

The seventh song is striking as its notation seems to indicate that it should be played only with the right hand. As Schönberg was not a pianist himself, as he was made aware of by others31 and he asserted many times,32 one might argue that he did not write a “pianistic” score. After all, the score does not contain any fingerings and only very few markings that indicate the distribution of the hands. Nevertheless, in this instance, I decided to follow the score. Although bars 9 and 10, in particular, are uncomfortable to play with the right hand alone, I did not to help with the left hand (as indicated in blue in the following example). Playing the song only with the right hand enabled me to feel a resistance in the phrases that helped me to convey the speaker’s pain and the agonising tension of the poem. This way of playing also allows the audience to perceive this tension visually.

Figure 11: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. VII, bars 9-10, fingerings

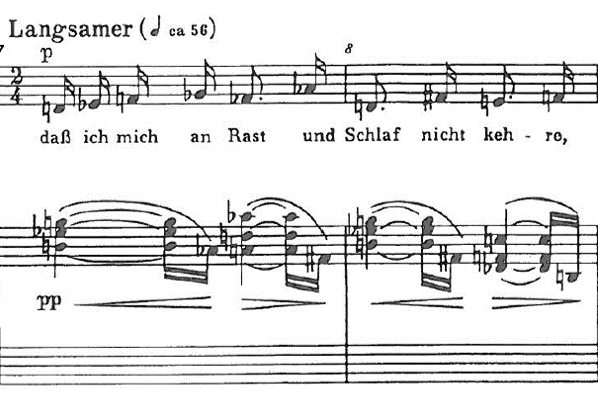

The eighth song is one of the two songs that are technically most challenging due to its fast tempo, rhythmical vitality, large register and dynamic contrasts. Starting each of the first three bars with the fifth finger and playing up to the thumb gives me a sense of stability in the left hand. The leaps at the end of bar 3 are particularly challenging, also due to the difficult coordination with the right hand. I like to practise the left hand alone, also when I rehearse with the singer, to get a feeling for the rising lines independently from the rhythmical interjections of the right hand.

Figure 12: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. VIII, bars 1-5, fingerings

Schönberg’s first fair copy33 contains the following fingering (in blue) that seems somewhat impractical to me considering the song’s fast tempo. Although it would be easier to play fortissimo with that fingering and it can be slightly awkward to cross the fifth finger over the thumb, I felt that my fingering (in red) gave me a much better momentum up to the octaves in bar 9.

Figure 13: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. VIII, bars 8-9, fingerings

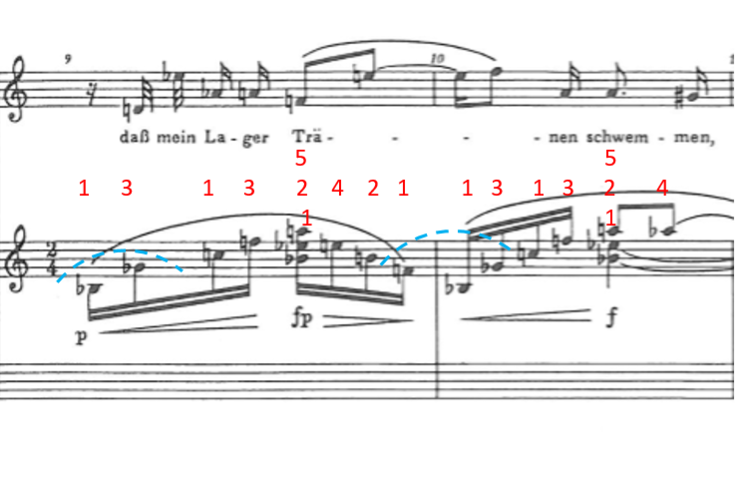

In the following example from the ninth song, I decided against redistributing the hands despite the extremely low register. The right-hand fingering felt more secure and allowed me to shape the line in continuous diminuendo to illustrate the poem text that depicts a desert that absorbs a raindrop.

Figure 14: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. IX, bars 13-15, fingerings

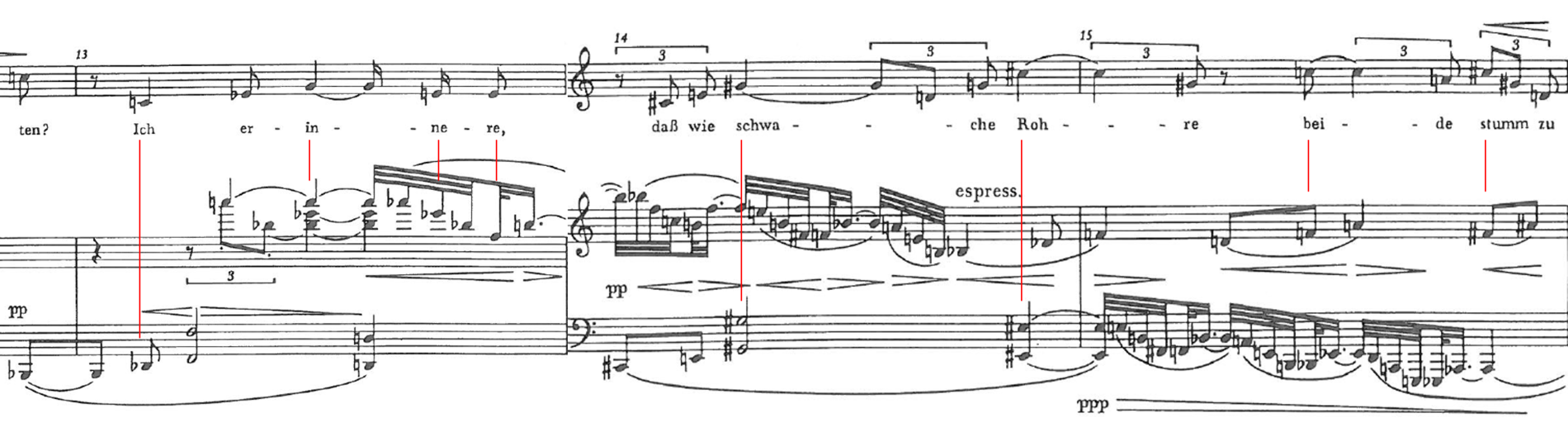

The tenth song contains an example of polyphony where my hands are too small to play all notes simultaneously the way they are written. Instead of distributing the parts as they are notated and breaking the left-hand chord on the third beat (by playing the bass note slightly early), I decided to follow the middle voices and to enter slightly delayed with the upper voice. I used pedal to create an illusion of legato when I played the fifth finger twice in a row. Even if one can play the left-hand chord the way it is written, the right-hand fingering would be inorganic at some place due to the two voices that are far apart from each other. The two fifth fingers seemed the best solution to me as I can use them to bring out the expressivity of the upper voice.

Figure 15: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. X, bar 15, fingerings

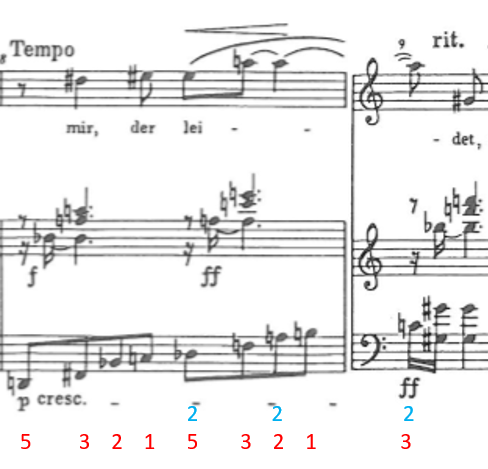

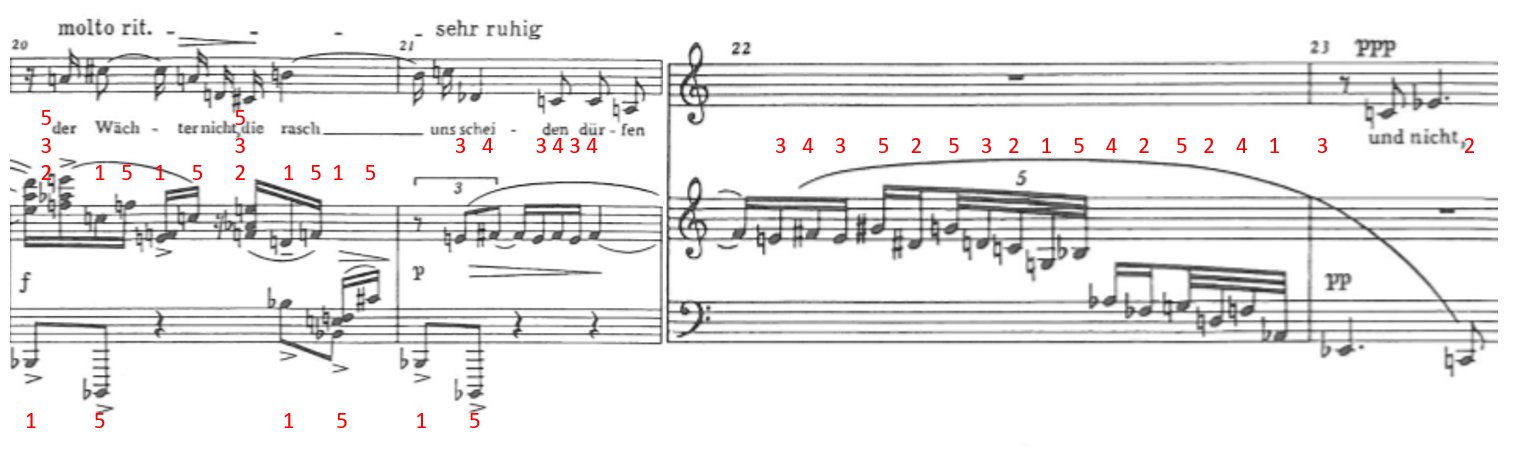

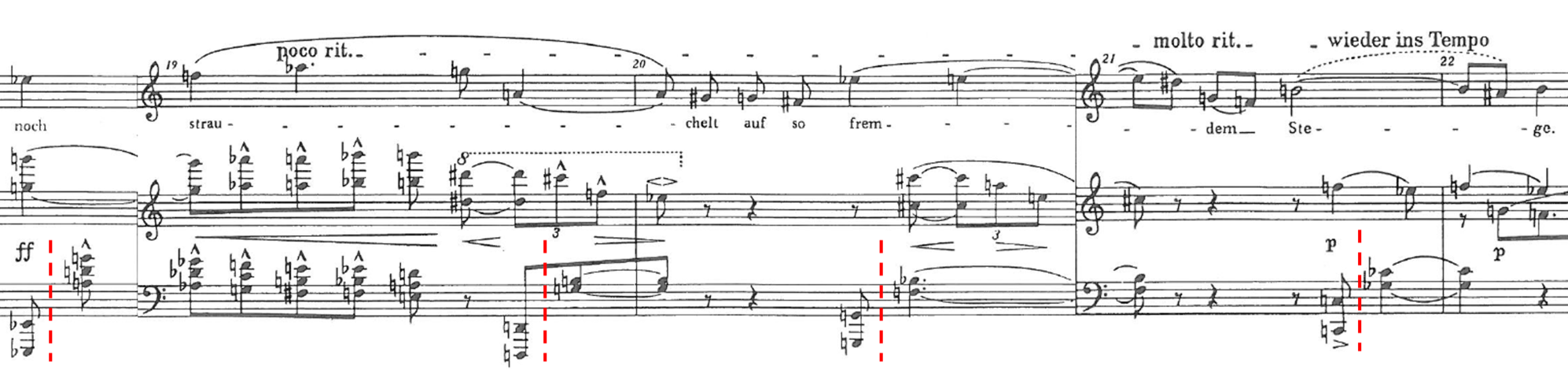

As I write in my description of the collaborator’s toolbox of skills, the molto ritardando in bar 20 of the twelfth song is challenging to coordinate with the singer. Part of the problem is the uncomfortable right hand that has to alternate between the fifth finger and thumb. In the following slower part, I decided again to keep the descending line in the right hand despite the low register as it is easier to feel the line in one hand.

Figure 16: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. XII, bars 20-23, fingerings

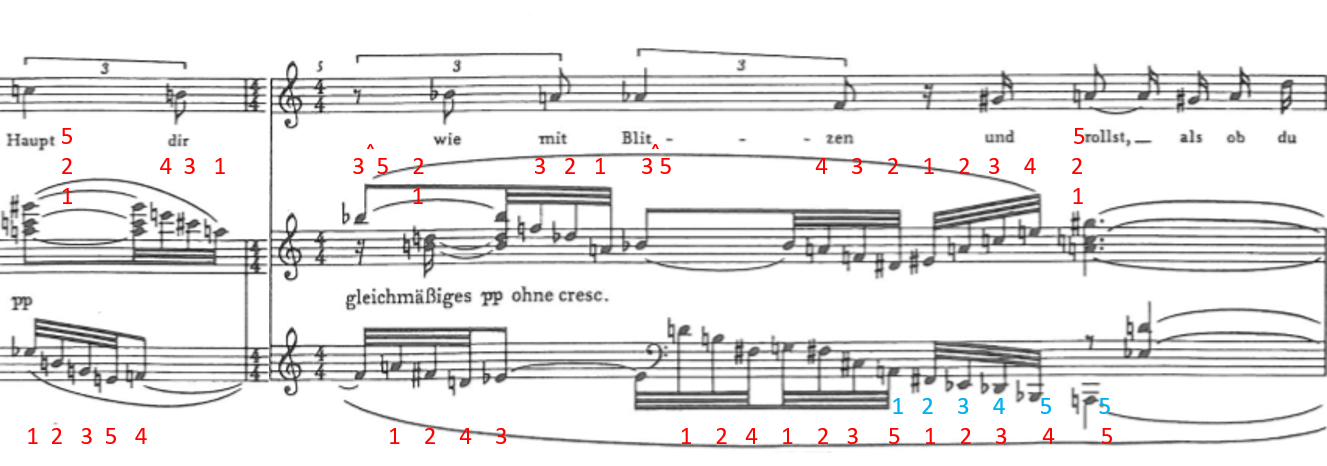

In the thirteenth song, crossing under the fifth finger seemed a good solution to manage the even pianissimo without crescendo Schönberg indicated in the fast thirty-second notes. I tried first a different fingering (written in blue in the example) that required me to slide on the fifth finger at the end of the phrase but found it less organic.

Figure 17: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. XIII, bars 4-5, fingerings

I decided to redistribute the parts at the beginning of the fourteenth song. Originally, I had played it the way it was written with the last note of the first bar in the left hand and the grace notes in both hands, but I discovered the advantages of taking all three notes in the right hand. I was better able to convey the lyrical fragility of the melody with the sighing minor second at the end of the first bar, and my new fingering naturally gave space for the singer’s first consonants. As I wanted to play the entire song without pedal I had to make small adjustments in bar 6:

Figure 18: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. XIV, bars 1-2 &6 , fingerings

One of the most intriguing places regarding hand distribution is the arpeggio in bar 19 of the fifteenth song. It marks a crucial point in the poem as the speaker realises the beloved will be gone forever. The way the arpeggio is notated with the g sharp on the lower staff might indicate that it is supposed to be played with the left hand as it seems impossible to play the g sharp as the third note of the arpeggio organically with the right hand due to the large leap down to the d that would stop the upward arpeggio-movement. If one reads the g sharp as independent from the arpeggio, two practical solutions come to mind. Either, one plays the g sharp with the right hand simultaneously with the bass note. This has the advantage of solving the coordination problem with the singer but is difficult to realise in tempo as the tenuto requires a little weight and the leap down to the d is still rather fast. Alternatively, one plays the g sharp last with the left hand as I did in all four concerts. This solution has the disadvantage of complicating the coordination with the singer. I discussed this chord with both my singers, but even though we arrived at the same conclusion, I might play an alternative version the next time I perform the cycle.

Figure 19: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. XV, bar 19

Inspired by the writings in Schönberg’s first fair copy,34 I decided to redistribute the parts in bar 24 of the fifteenth song, one of the technically most challenging places of the cycle. I had discarded the possibility of redistribution when I learned the song for the first time as I found it too complicated, but attempted it again after the first concert. Alternating the hands in the leaps between two fifths allowed me to play the bar without pedal and thus clearer and softer at a place that starts pianississimo. In the foreword of the piano pieces Op. 23, Schönberg wrote: “In general the best fingering is that which allows an exact interpretation of the note groups without the aid of the pedal.”35 My second singer, in particular, inspired me through her non-legato articulation to play these two bars as dry as possible. Only the climax in bar 25 needs a little pedal, both to connect the notes under the small slurs and to add sonority to and sustain the left-hand chords in the high register.

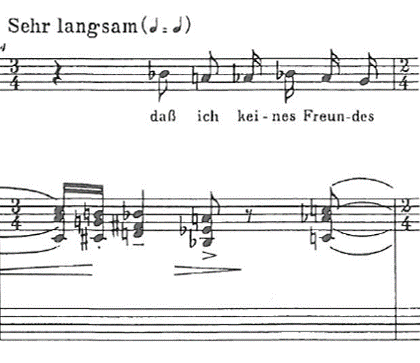

The topic of pedalling is both related to fingering, as the right (sustaining) pedal can be used to connect tones which cannot be held by the fingers alone, and to tone colour. As Neuhaus wrote, “[…] one of the main tasks of the pedal is to remove from the piano’s tone some of the dryness and impermanence which so adversely distinguishes it from all other instruments.”36 When the sustaining pedal is pressed down, all dampers are raised, and as a result the strings that are harmonically in sympathy with those played vibrate as well. This creates a warm and rich sound. According to Rosen, “[b]eginning with the 1830s, the almost continuous use of the pedal became the rule in piano playing”.37 Schönberg, however, seemed to have favoured a thinner and brittle sonority. In his essay The Modern Piano Reduction (1923), he wrote: “Anyone writing for the piano should bear constantly in mind that even the best pianist only has one pair of hands, though he also has a pair of feet, unfortunately, which now get in the way of his hands, and now help them on their way. The feet sometimes know (as and when required) what the hands are doing; and while on other occasions they take no notice of it whatever, they still give monotonous and reliable support to the main aim of all present-day piano playing: the suppression of any possibility of a clear, pure sound. These feet, together with the pedals appertaining to them, make piano-playing more and more into the art of concealing ideas without having any. As remarked, this fact must be taken into account by anyone who wants to write for the piano. And the only way is to write as thinly as possible: as few notes as possible.”38 Nevertheless, Steuermann, Schönberg’s pianist of choice, did not follow Schönberg’s instructions to the letter but rather used his understanding as a pianist to negotiate them in his practice. He said on the subject: “Schoenberg always insisted that his music be played almost without pedal which, frankly, I obeyed only halfheartedly. You cannot play the modern piano without pedal. You have to use it, of course, so that the tones are not blurred, and to make sure that the “sober” sonority without pedal vibration, which is so characteristic, comes through.”39

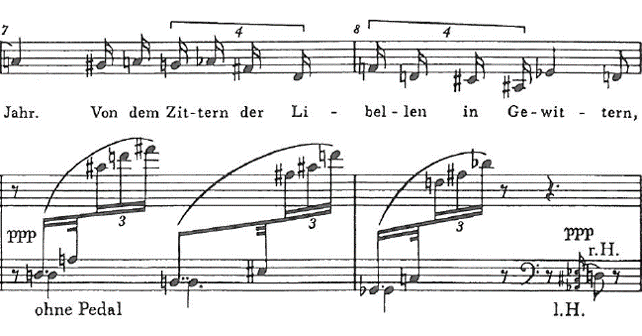

Opus 15 contains almost no pedal indications. Schönberg only indicated “ohne Pedal” (without pedal) three times in the cycle: once at the beginning of the sixth song and twice in the fourteenth song (bars 1 and 7). Nevertheless, I play several other places without pedal, particularly because in polyphonic textures pedalling can make it difficult to differentiate and articulate the voices independently as the sound becomes thick and blurred. Also at places with single voices, I sometimes use little or no pedal depending on the emotional content of the poem and the colour I associate with it. One such example is the piano introduction of the first song. I immediately want to draw the listener into the sound world of the cycle and play it entirely without pedal until the sforzato before the second voice enters.

The idea of playing the technically challenging part in bar 13 without pedal can be frightening, but inspired by writings in the first fair copy40 I use almost no pedal. The clear articulation of the left hand needs a little practice, particularly the major second that has to be played simultaneously with the second and third finger, but the similarity of the hand position for each of the figures made the challenge manageable. The following bar is also marked “without pedal” in Schönberg’s first fair copy. Here, however, I like to add a little sonority to the longer chords.

Figure 21: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. I, bars 13-15

Around and after the climax of the third song, it is tempting to keep the bass octaves in the pedal. I found it, however, much more intriguing to change the pedal. This way, the two voices appear clearer and more independent. The clarity is also necessary for purely practical reasons as a blurred sound can make it difficult for the singer to hear my way of shaping the transition back to the tempo of the beginning under her long note in bar 21.

Figure 22: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. III, bars 18-22

In the fifth song, the homophonic, chordal texture and the pull towards resolution into the “tonic” G invite for a more generous use of the sustaining pedal. In contrast, Schönberg marked the beginning of the sixth song “without pedal”. I nevertheless use pedal to create the fortepiano effect at the end of the first bar by playing the octave very short in the pedal, releasing the tones and playing them again silently before I lift the pedal. Although Schönberg’s pedal indication might only pertain to the opening chords, I like to continue the following phrase without pedal as I find the resulting fragile sound more suitable for the speaker’s fantasies of the beloved. Only gradually, I add a little pedal to bring out particularly expressive melodies. I have noticed that my use of pedal in this music is connected to the idea of expressivity. Each time Schönberg marked a phrase as espressivo, I seem to play with pedal. If I use the pedal otherwise sparingly, the effect gets much stronger.

Figure 23: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. VI, bars 1-2

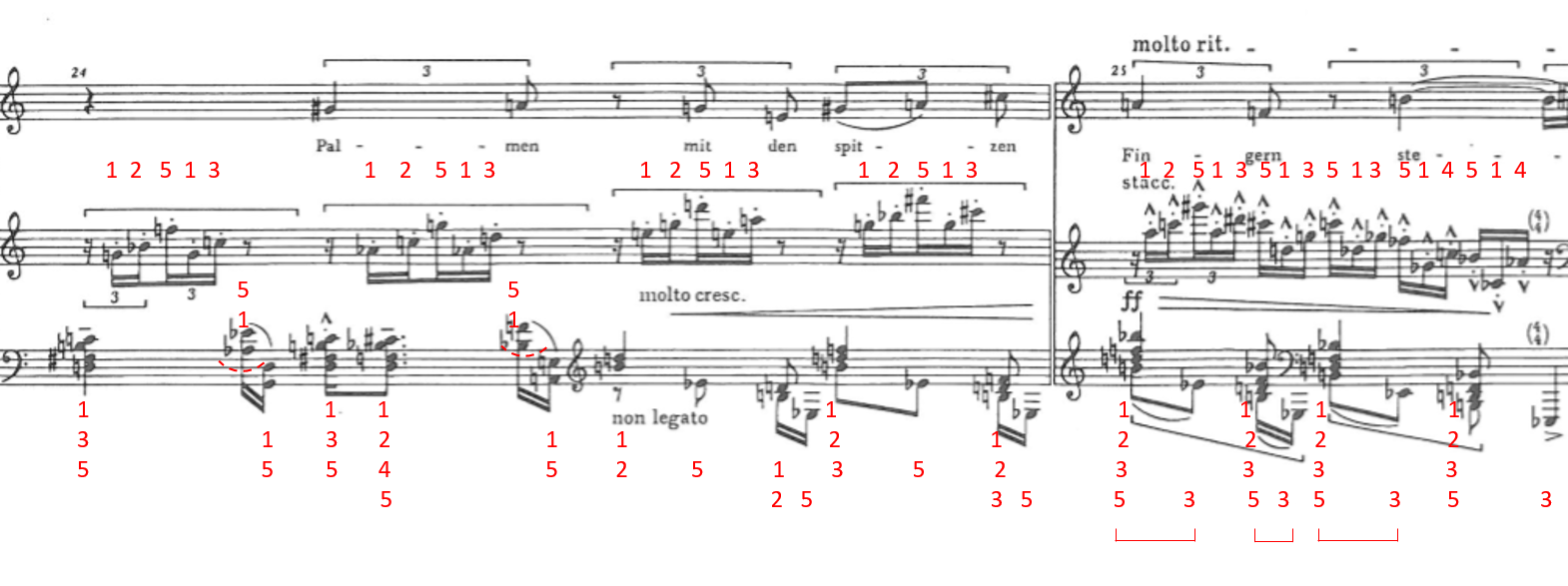

If a sostenuto pedal is available, it can be very useful for articulating clearly in one voice while holding notes in another voice. In my third concert, I used the middle pedal especially in the last song. As I wrote in my reflections on the poetry, a clear articulation helps me to convey the threatening images of the disintegrating garden and the icy quality of the surface of the pond, yet due to my small hands, I have to break some right-hand chords if the piano does not have a sostenuto pedal. I also experimented with the middle pedal in bar 25 of the same song. I found I could play the marked staccato that illustrates the “pointed fingers” of the palm trees much clearer when I used the middle pedal instead of the right pedal. Timing is crucial as the sound immediately disappears if either the pedal is pressed down too early or the fingers are lifted too soon. Therefore, I decided to alternate between the two pedals, holding the longer notes with the sostenuto pedal whereas I used the sustaining pedal for the shorter notes.

Figure 24: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. XV, bar 25, fingerings and pedal

As Katz remarked, “[i]nstant color changes are available with the left foot on most instruments. Be sure, however, that this pedal is not being overused to control the balance, or the color manipulation that we need for character changes becomes obscured.”41 Although it is tempting to use the una corda pedal for the soft dynamics Schönberg required of the performers, I try to use it mostly for purposes of colour rather than dynamics. However, I sometimes trick myself into playing softer by putting my foot on the left pedal without pressing it down.

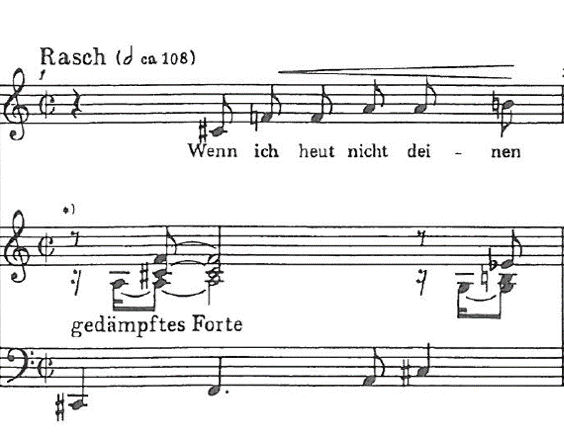

The score of Opus 15 contains no una corda indications. However, the beginning of the eighth song is marked “gedämpftes Forte” (damped forte). One might wonder if Schönberg refers here to the moderator pedal of early Viennese pianos like he seems to have done in his piano pieces Opus 11. However, Voigt points out that “neither in the Schoenberg-Busoni correspondence nor in other sources is the question of a third pedal ever raised. Schoenberg in all three pieces of the Op. 11 cycle asks for a “moderator pedal” (In German “Dämpfung” or third pedal) […]. What he had in mind was a strip of cloth or felt which damps the sound to ppp (e.g. Piano Piece no. 1 bars 12-14). The early German and Viennese pianofortes did have a register called “moderator”, and Viennese instruments through the middle of the 19th century often had a moderator besides the una corda pedal. But no instrument around 1900 is known as still possessing a moderator pedal, if one doesn’t count upright pianos.”42

In December 1941, Schönberg received a letter43 from Arthur Mendel, a representative of the publishing company that wanted to print an American edition of his piano pieces Op. 11 and Op. 19. This letter deals with possible translations of the German terms in all pieces. Mendel had discussed them with Schönberg’s son-in-law Felix Greissle and his favourite pianist Eduard Steuermann. In addition to the translations, he suggested printing the German originals as well. Attached to the letter were their concrete suggestions. Both the letter and the attached pages contain handwritten notes by Schönberg. He seems to have had no problems with the translation of “Dämpfer” as una corda. He readily agrees with Mendel’s suggestion of removing the indications “mit Dämpfung bis” and “3. Pedal” and substituting them with una corda, as his handwritten “yes” suggests. I decided to play the first two bars of the eighth song with the una corda pedal.

Regarding dynamics, it is interesting that Schönberg advised his students never to write mezzo-forte44 and often complained about performers not playing soft enough where the music required it, as they were too occupied creating a beautiful, carrying tone, which Schönberg called “mezzofortissimo”. 45The notated dynamics of Opus 15 range from pppp in the eleventh and fourteenth song to fff in the eighth and fifteenth song, but the soft dynamics predominate the cycle. Kerrigan gives a detailed description of all notated dynamics in her pedagogical study of Opus 1546 but does not write much more than the repeated advice always to follow Schönberg’s indications. If one considers that performers who study this work are most likely advanced musicians, her many obvious descriptions of dynamic markings or sentences like “This passionate song should be interpreted with careful attention to all directions, including the eleven crescendo, decrescendo and tempo markings”47 provide few insights into the music or its performance. Dynamic shades are difficult to describe verbally, as “there are more varieties of tone and colour than there are labels such as piano or pianissimo to tag on them”48 and are influenced by factors such as the acoustics of the hall, the range of the instrument or the singer’s voice. I nevertheless try to elaborate on some of my views regarding dynamics and colours in Opus 15 in this reflection. As they are influenced by my perception of the poetry, I describe most of them in the section that is dedicated to the words, whereas the following short part focusses mainly on my conception of the cycle as a whole and some practical aspects.

Although I started out with a reading as close as possible to the notated dynamics, I soon discovered that even two songs with a similar dynamic range had dynamics with different qualities. In my performances, I found it important to convey these qualities and the build-up and release of tension throughout the cycle that contains five complete songs whose notated dynamics do not exceed piano.

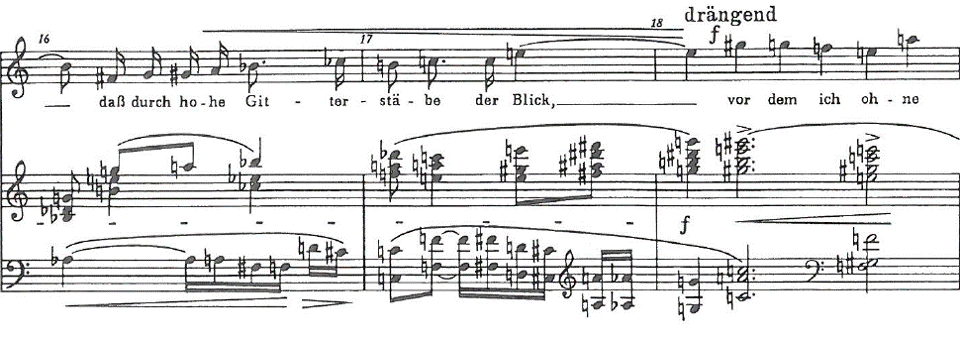

I start the first song very softly in a slightly mystical yet clear and carrying pianissimo with left pedal. The entire song stays rather soft to contrast the climax in bars 17 to 19, where I try to bring out the percussive accents without interfering with the singer’s pronunciation and to convey the increased energy without exceeding the limits of forte as there is still much to come. Nevertheless, the soft dynamics have different shades. When the “gentle voices tell of their suffering”, I can use the tension of the chromatic line and play the right hand very intensely despite the pianissimo marking. I also play a slight crescendo in the left hand to bring out the outer voices that move chromatically away from each other.

Figure 25: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. I, bars 11-12, dynamics

The second song is one of those that stays soft throughout, yet I find it important to have a less mystical, more open sound to convey the changed atmosphere of the poetry, so I avoid the left pedal in this song. The third song starts like the two previous in pianissimo, which again has a different quality with an underlying energy and searching tension. The rhythmical energy might tempt both performers to start too loud. In bar 7, the pianist encounters for the first time in the cycle the seemingly unrealisable marking <> over one chord. Cramer points out that “few performance indications in the Vienna School’s score can be taken literally”49 and that “[i]n general, members of the Schoenberg Circle treated the score as an inadequate transcription of the composer’s “real musical vision,” whose conversion […] into musical notation was imperfectly done under the duress of having to commit a musical idea to paper.”50 Schönberg dismissed Busoni’s objection to the use of <> over single chords in Op. 11. In an undated letter, he wrote: “I actually added this marking later and have since made continual use of it with specific meaning. Naturally, I never imagined that one could make these chords grow louder and softer. […] In such cases, I always mean a very expressive but soft marcato sforzato. Roughly comparable with the portamento marking or the like.”51 Despite the detailedness of his scores, Schönberg’s markings are not necessarily meant as fixed prescriptions for the performer but as “an aid to comprehension”.52 The markings appear again at the climax of the third song, the first time Schönberg indicates a fortissimo in the cycle. In practical terms, they seem to be more closely connected to the issue of timing than dynamics. I put my weight on every note but still feel a kind of pent-up energy and broadening. The sound I want is more round than sharp.

Figure 26: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. III, bars 7 & 16

The tension grows further in the fourth song, which is the first to begin in piano and needs thus a more intense sound. Nevertheless, we found it most effective to keep the dynamics rather soft throughout the first page despite the expressive hairpin markings. After the climax of the song that this time is only marked forte yet seems more intense than in the previous song due to the higher pitches, Schönberg marked a quick diminuendo back to piano. Kerrigan remarks on the importance of observing the soft dynamics after the dramatic build-up,53 but I find it also important to keep in mind the connection in the sentence of the poem text. Considering the continuing diminuendo until the end of the song, I rather think of bar 21 as mezzo piano and avoid the use of the left pedal as long as possible.

Figure 27: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. IV, bars 19-22

Although the fifth song starts like the fourth in piano, the speaker’s growing urgency and the physical feel and auditive qualities of the chordal texture invite for a warmer sound, which makes this song perhaps the “richest” of those five marked piano or softer. Different shades help to bring out the images of the poem. The sixth song is the first to start in forte with three sharp staccato duro chords. In this song, I found it particularly important to bring out the clear contrasts that convey the difference between the speaker’s fantasies and reality. I use the una corda pedal at certain places related to the speaker’s fantasies to create a more fragile sound. The seventh song starts again in forte. The tension increases further yet due to the textural bareness the song is less “loud” than the previous one. I nevertheless think of it as “sharp” and make sure that whole chords and not just the upper voice sound. Particularly at the beginning of the song, I make much more out of each small crescendo and decrescendo than in previous songs, being careful to start each crescendo softly instead of getting caught up in the agitation, so I do not reduce the effect. The eighth song has the largest dynamic span so far, which can be difficult to convey in the fast tempo. I found it useful to practise the song slowly and exaggerate the contrasts. I use the left pedal in the two first bars to bring out the “damped forte” before the steep crescendo towards fff. This is one of the songs in which I am most aware of dynamic differences between the hands. In the start, I play the left hand more dominantly letting the right hand gradually increase to give space for the singer’s articulation of the text. In bar 8, however, the roles are reversed. Although the left hand still “leads”, the interjections of the right hand are much louder. It can, however, be impractical to start the left hand too softly as the singer has to hear it to coordinate her entry in tempo and can get confused by the impulses of the emphases of the sixteenth notes before the chords Schönberg asked for.

Figure 28: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. VIII, bars 1 & 6-8

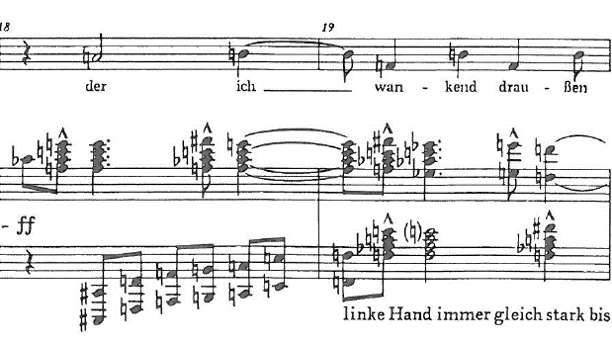

The end of the song poses balance problems. Although Schönberg’s prescription “linke Hand immer gleich stark bis zum Schluß” (left hand always equally strong until the end) asks for an incessant pounding of the raw and marked accents, it is essential to keep in mind that the end is only marked fortissimo and to listen to the singer’s voice in the rather low register.

Figure 29: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. VIII, bars 18-19

Although the ninth song begins again in piano, it is important not to lose the tension after the outburst of the eighth song. Dynamic contrasts are again important, yet even the piano sounds harsh and “bitter”. The piano introduction of the tenth song is marked forte, whereas the rest of the song contains only indications of soft and very soft dynamics. Nevertheless, I do not start the song very loudly but think the forte rather soft and round with a warmth similar to the piano opening of the fifth song. When the singer enters, the different images of the poem require corresponding qualities of piano and pianissimo often with different shades in the right and left hand. I perceive the eleventh song as the softest and most fragile of the entire cycle as both parts feel very thin and exposed. After the physical strain from the previous songs, it can be challenging to play as softly as possible without losing any notes that are crucial for the coordination of the ensemble. The twelfth song is again more emphatic and intense, particularly in the left hand of the middle part. Although the end is marked ppp and I try to play the left hand gradually softer, the sound has to be distinct to convey the horror of the poetic image.

Figure 30: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. XII, bars 23-28

Both the thirteenth and the fourteenth song have very soft dynamic indications. Nevertheless, the thirteenth song starts with a “sting” and needs contrasting colours to convey the two opposing poetic images of the beloved’s defensiveness and the speaker’s melancholy and despair. In contrast, the pianissimo of the fourteenth song feels both lyrical and fragile and reminds slightly of the colours of the eleventh song. In the final song, which has the largest dynamic span, I attempt to recapitulate the whole range of dynamics and colours. The technically challenging and rhythmically complex part around bar 22 can be difficult to play soft enough. Despite the ppp-marking, I avoid the use of the una corda pedal as it makes the sound less articulate and focussed.

According to Cramer, “Clean, proficient performances were not [Schönberg’s] goal. His musical standards were matters of expression, not of technique or school learning. And if one could not achieve the proper expression, the next best thing was still not technical mastery but personal conviction and passion.”54 Despite his tolerance for poor technique, he demanded observance of the score and polyphonic clarity. Steuermann stated: “The essence of Schoenberg’s piano style, like the essence of his entire musical thinking, is polyphony.”55 And in a letter to his students and friends from December 1920, Schönberg wrote: “And our goal: to make everything audible, graduated according to significance, and at the same time obtain a “homogeneous” sound”56 and later in the letter: “[…] today’s fashion of emphasizing one voice by playing it strongly and everything else softly seems more and more intolerable to me. These days everyone does that completely mechanically, though at one time it may have been an interpretive expedient. I believe that must increasingly done differently: Each voice must have life, be somewhat expressive, and that is only possible if the interpreter has a concept of the total sound.”57

In hindsight, this concept of the “total sound” is one aspect that has perhaps developed the most in my playing of Opus 15. When I started my study of Opus 15, I tended to overemphasise the upper voice at the expensive of the full harmony. Although I realised this defect already before my first concert, I needed to get used to Schönberg’s sound world to develop a more nuanced voicing and was particularly inspired by Glenn Gould’s recording to search for polyphonic clarity and each voice’s individual character. At the early stages, I seemed to have been guided too much by an ideal of tonal beauty that Schönberg opposed.58 As Rosen describes, “[…] for pianists, there are certain specific but limited kinds of sonority and also certain aspects of what has traditionally been accepted as expressive playing that are thought to be indispensable for any public presentation. Playing with what is called a beautiful sound is supposed to be essential: what this generally means is by common consent restricted to a style of execution in which the melodic voice is set slightly in relief over the accompaniment, violently contrasting accents are avoided, and the pedal is used throughout but with discretion, avoiding any suggestion either of harmonic blur or of a dry sonority.”59