Into the Hanging Gardens - A Pianist's Exploration of Arnold Schönberg's Opus 15

Return to Contents Bibliography

Introduction | Playing (with) the Words | Schönberg's View on the Importance of Text of for the Performer | Playing Lieder with Texts by Stefan George - Contextualisation I | Translation | The Poem Texts of Opus 15: Song I | Song II | Song III | Song IV | Song V | Song VI | Song VII | Song VIII | Song IX | Song X |

Song XI | Song XII | Song XIII | Song XIV | Song XV

“In true poetry, like in nature, core and shell are so much one thing that a part of what is meant reaches us in a way that is untraceable to the mind.

We never get inside the poetry, but it is a rare and high pleasure to walk around its creations and perceive a thing or two.”

(Hugo von Hofmannsthal)1

I started the project by exploring the poetry of Opus 15 and playing it in the context of other Lieder with texts by Stefan George in my first concert. It seemed sensible to begin with this contextualisation as I usually approach Lieder through the poetry and care very much about the text in my practice. Although the singer articulates the words, they are also important for me as a pianist. There is often limited time in the day to day work of a collaborative pianist, but understanding the meaning of each word of a poem and knowing how it is pronounced is essential preparation for any kind of collaborative work with a singer. I often encounter students, both pianists and singers, who only have a rough understanding of the texts of Lieder, and wonder how they can perform the music without being aware of all the inspiring possibilities the poetry offers. While “playing the words” as a Lied pianist is a common practice that is connected to certain skills in the “collaborator’s toolbox”, as I will show in the following section, the complicated poetry of Opus 15 that can be difficult to understand even for a native speaker is covered sparsely by existing literature. Translations can be misleading as they cannot convey all aspects of the original. Kerrigan is, to my knowledge, the only one who wrote about the poetry from a performer’s perspective.2 I believe, therefore, that my insights as a pianist and native-speaker might be interesting for others.

When I planned the project, I thought about the different contextualisations more as an organisational device and audience-friendly approach to the concerts than as a method for artistic research. Each of the contexts offered a new theoretical access point to Opus 15, but during the project, I realised that each context also had a unique effect on my artistic practice and offered the possibility to answer artistic questions that arose out of the specific context. In the first contextualisation, two questions became most interesting:

- Does it work to approach Opus 15 through the text despite Schönberg’s warnings to the contrary? That means, can I transfer my practice of “playing the words” to this repertoire?

- Is there a particular “performative feel” to Lieder with texts by Stefan George?

In the following sections, I first elaborate on a more general level on how the text can influence me as a pianist and how I “play the words”. I then discuss Schönberg’s views on the importance of the words for the performers and how I negotiated them in my practice, before I explain my attempts to get “behind” the poetry and George’s way of writing, and expand on my two questions as I describe the effect of the first contextualisation on the artistic process. In the fourth section, I elaborate on my translation work and how it affected my understanding of Opus 15 as well as my perception of my artistic practice. Finally, I discuss the texts of all fifteen songs, trying to convey nuances a non-native speaker might miss and highlighting those aspects of the texts that became important for me as a pianist. My ideas on how I deal with words and how they affect my practice in general have not changed considerably during the project unlike for example my view on collaboration. Therefore, while both my understanding of the poetry of Opus 15 and my treatment of it in my practice developed during the project, it is difficult to describe this development. A new discovery or a different understanding of a word or an ambiguity would suddenly add a new layer to my interpretation that would either cover or complement previous layers making it difficult to remember my previous ideas. My discussions of the poetry of Opus 15 should not be read as a straightforward, set understanding but as a collection of elements that belong to this development. Where it is possible, I show how my understanding changed and which consequences these changes had for my playing.

Lied is a small art form with nuanced details and quick changes. The text of a Lied and the way a singer moulds the words can affect the pianist in the development of almost all performance parameters. Thus, the ability to deal with and understand the text on different levels is an essential competence in the Lied pianist’s “toolbox of skills” that is needed to achieve both synchronisation and expressivity in a Lied performance.

Although there are small differences in the practical approach of Lied pianists to poem texts, today, there seems to be a general consensus about their importance for the pianist. According to Moore, “[t]he first thing an accompanist should study when he has to play a new song is the words. […] The composer did not write the vocal line first and then fill in the piano part afterwards; they were both born in his brain at the same time. Therefore the accompanist and the singer, the one no less than the other, owe all to the words and depend on the words to guide them”.3 Katz remarked similarly: “With vocal music the text is always the guide of how to proceed. How it is pronounced and how it is shaped tell us more than the most complex rhythmic notation could ever capture”.4 Stein and Spillman emphasise the importance of starting with the text in the performance preparation of Romantic Lieder: “[The performers] must study first the poetry, then the performance problems, and then each aspect of the musical structure in turn. By the end of the process, a recombination of the three topics will occur through polished performance, when singer and pianist convey their understanding of the poetry and the music in the magical act of musical expression.”5 At a masterclass at the University of Hull in November 2016, Malcolm Martineau also recommended studying the text before learning the music. However, he agreed with an audience member that each performer must find their individual way of learning and that a simultaneous study of words and music can be an equally valid approach.6

The following general reflections on how the text can affect the pianist, and how he or she plays (with) the words, are both based on my experiences as a Lied pianist and described in the existing literature on the topic.In my view, the pianist must consider the text on three different levels.7 First, words are combinations of sounds and have thus an immense impact on the way the singer’s instrument is perceived. The text’s sound qualities influence aspects of synchronisation and balance but can also have an impact on the pianist’s tone colour. Singers produce a carrying sound on vowels, and therefore it is important for the pianist to play on the singer’s vowels, not before. Playing on the consonants sounds imprecise and causes balance problems as the consonants can be drowned out easily. Also, the singer might feel pushed if he or she gets the impression the pianist is constantly early. German texts, in particular, tend to have accumulations of consonants within words or at word boundaries that require the pianist to adjust his or her timing in small nuances. The singer, on the other hand, should also know that the pianist plays on the vowels and that some words might have to be pronounced early. The pianist can often use the singer’s consonants as indicators of the following vowels. A singer’s shaping of diphthongs can also give clues about his or her inner pulse. Familiarity with the singer and understanding of the text’s figurative and semantic aspects can help the pianist gain a sensitivity for the singer’s varying speed of pronunciation and ways of shaping diction and thus make synchronisation easier. The sound of words is not only a result of the order and combination of vowels and consonants. Words and groups of words also have an intonation, the rise and fall of the voice, which depends both on grammar and content, underlines important elements of the message and conveys the speaker’s emotions. As the composition dictates pitches and rhythms, not all aspects of spoken intonation can be directly transferred to a musical performance. Some composers follow the natural intonation of language in their Lied settings with complex rhythms and melodies that follow speech patterns, whereas others might just write beautiful melodies and leave the shaping of the words and sentences more to the performers, but the intonation of the language should always be considered as without it, the words would sound mechanical and lifeless.8 Even the most detailed score cannot capture all the subtle nuances of intonation that the performers convey through phrasing and rubato, dynamics and tone colour. The pianist needs flexibility and a rich variety of tone colours and dynamics to convey aspects of intonation, which are particularly important when the accompaniment is in (rhythmic) unison with the singer’s part or imitates the singer’s material. When I play with a singer, I negotiate multiple “personalities” at once as I follow the singer’s voice yet make my mind believe that I sing myself while simultaneously following and shaping my own voices. Focussing on the text and its intonation is a huge help in the give and take of the collaboration. The sound of a text also affects the way colours are created. Different vowels have darker or lighter colours, and consonants and consonant combinations can have various qualities, like being harder or softer, voiced or voiceless. Repetitions of sounds can create different moods and contribute to the perception of the form of a poem. Depending on the context, the pianist might try to blend with the singer’s colours or contrast them. The different qualities of certain vowels or consonants also influence their projection and thus the balance between voice and piano.9 A knowledge of the sounds (in connection with the meaning) helps me also to judge the singer’s timing as I know how much and what kind of effort certain words take.

Second, both singer and pianist should consider the figurative level of a text. Poetry often uses images or metaphors which might be reflected in the music, both in the foreground as tone painting or in the larger structure of a work in the form of recurring motivic symbols. The awareness of the poem’s figurative level and the understanding of possible connections between the text and the music influence the performers in their search for an appropriate tempo, articulation or colour. Depending on the context, the pianist, like the singer, might choose to underline or conceal these figurative elements.

Third, the large-scale aspects of the text, its syntax and meaning affect the performers’ decisions. They, together with the music, influence the singer’s points and ways of breathing and thus also the pianist’s timing and phrasing. Katz distinguishes between three categories of situations involving breath. In the first kind of situation, there is no need for the pianist to adjust as the singer can breathe well, sing a phrase and has enough time to take a breath before the next phrase. The second kind of situation, when voice and piano are in rhythmic unison and the singer needs time for a breath, requires the pianist to wait and hold the sound unless the dramatic effect of complete silence is desired. The third kind of situation occurs when the singer needs time to breathe while the pianist plays one or several other voices. Under these circumstances, the pianist must take extra time, though not together with the singer. Instead, the pianist should phrase slightly before the singer and then continue without stopping or slowing down as that would disturb the flow of the music and the singer’s natural way of breathing.10 Although I recognise these types of situations in my own practice, Katz’ descriptions are very generalised. The adjustment of phrasing at breath points is not only important for the singer’s comfort and the flow of the music. Breath is also an expressive means and can reveal the singer’s intentions to the pianist. Its timing and speed are related to the emotional aspects of the text, and therefore even situations of the first type might require subtle adjustments from the pianist. In addition to these considerations, the pianist must be aware that the breath capacity of a singer is limited. In particularly long phrases, the pianist must carry the singer to the next breath and pay attention to balance and tempo. Occasionally, a composer might not respect the sentence structure of the poem and interrupt a sentence with accompaniment material before the singer is allowed to continue. In cases like these, it is often necessary to feel a connection between the phrases instead of phrasing with a sense of closure.

For the pianist, the text’s content also gives important clues for the shaping of introductions, interludes and postludes. Depending on the poem and the song, they can have many functions: they can set the scene, prepare or change a mood, convey or even trigger the speaker’s feelings, relive an experience or continue the story. The content of the poem does not only give hints about the general mood but can affect both players in the shaping of small details. Sometimes, a subtle change of tempo or “perceived” tempo is needed to give more space for a poetic thought or convey the urgency of the emotions that are expressed in the text. If I take into consideration the poem’s textual and emotional aspects, I can find a motivation for the sound I produce. This does not mean that I play “emotionally”. A certain distance is still necessary for making a performance work: I do feel the emotions of the text deeply but not as if they were my own. The poem might contain questions, answers, statements, retorts, suggestions etc. These might be mirrored in the music’s harmonic or melodic progressions, or in changes in register, tempo or dynamics, which I might choose to enhance in my playing. Related to the content of the text is the question of persona. Both the singer and the pianist should ask themselves who the speaker of the words is and if the persona changes over the course of a Lied. In cases when the accompaniment mirrors the persona(e) of the vocal part, subtle variations in speed, articulation, rhythmic vitality, balance between the hands and tone colour including different use of pedal can help depicting their characters. The accompaniment might also have an independent role, adding a subtext or strengthening and continuing or contrasting a previous idea to show irony, for example. The words might also be spoken to a certain degree by the poet, or even, especially if the poem is less narrative and more philosophical or universal, by the composer or the performers. Poetry can often have several layers of meaning. The performers might decide either to highlight a certain layer or to perform in a more ambiguous way. This ambiguity can also be necessary if the text contains a surprise. Even though both performers know the words that are to come the tension has to be just right to convey an unexpected turn of events to the audience without making it illogical. Like in speech, timing is essential in the telling of a joke.

Understanding the implications of the text on all these levels is perhaps the most essential skill of a pianist who works with vocal music. When I work with the text, I usually do not consider the three levels independently from each other in a systematic way. For some of the above-described elements, my approach is internalised and even to a certain degree automatized. For example, I play intuitively on the singer’s vowels. The text is with me all the time, almost like an additional voice, a “wire” to my collaboration partner and a door into the figurative and emotional possibilities of the music. I rely on previous experiences, my knowledge of what works and what I have to do in small nuances to make it work.

The pianist’s intense involvement with and examination of the text creates an affective bond, a sense of ownership of the work that he or she shares with the singer. It can also create a feeling of dependency on the singer, who shapes the text, while the pianist can only inspire and add depth. In a less ideal collaboration, this sense of dependency can cause frustration. Nevertheless, I prefer to work with music that has a text or at least a program as it helps me to make sense of what I do and limits the seemingly endless choices I can make. Katz appropriately compares the text to a pair of glasses through which the performers read the music.11 “The moment text enters the picture […] the options are narrowed, the pictures become clearer, the emotions are more specific. The words tell us almost everything we need to know.”12 While, on the one hand, the text narrows the options, it also helps the performers to access their imagination. As Bos remarks, “[…] it is the opening up of new and hitherto unforeseen vistas which make possible the continuance of one’s artistic development and the attainment of heights which may only be scaled through imaginative flights. The new vista opened up to me revealed the underlying principle in clear perspective, being merely the natural, appropriate treatment expounded in Hamlet’s famous instruction to the layers: ‘Suit the action to the word; the word to the action.’”13 An anecdote from Bos’ practice makes the liberating power of the text discernible: After he had accompanied the premiere of Brahms’ Vier Ernste Gesänge, Brahms came to the artists’ room to thank the artists for their performances, “which had, so he said, perfectly realized his intentions.”14 Two weeks later, Bos accompanied the work in a higher key, again with Brahms present. The singer felt that the final repetition of “die Liebe ist die Grösseste unter ihnen” demanded a climactic effect rather than the reflective diminuendo and piano that Brahms had marked in the score, and he asked Bos to continue this idea in the postlude, ending it triple forte. After the performance, the singer asked Brahms if he minded the climactic ending, and Brahms answered “You sang them magnificently. I did not notice anything wrong.”15 Most performers, myself included, are trained from early on to respect and follow the composer’s markings at all costs. However, this alone does not create art. I believe that the artistic involvement with the poetry can be useful in the development of interpretation as it enriches the “thickening process”16 from the score to the interpretative idea. The text can help both performers to create an artistically meaningful performance, even though it might go against the composer’s markings at times.

Schönberg's View on the Importance of Text for the Performer

When I started the project I knew little about Schönberg and his music, but I was aware of his controlling attitude towards performance, of which his carefully marked score of Opus 15 gives evidence, and I was familiar with some of his remarks against performing vocal music in a way that is too declamatory and guided by the text instead of the music. Therefore, I had some misgivings about my first approach to Opus 15. Although it seemed natural to start with the poetry as I did in most Lieder I worked with before the project, I was wondering if my attempt to get to know Opus 15 through the words, even though that was just the first of three “access points”, would really help me gain a better understanding. After all, according to Schönberg, if music is to be understood “the performer must be the advocate of the work and of its author. It must be not merely an honour but a pleasure for him to be able to present this music […]”.17 Perhaps it could even be considered an unethical move to approach Schönberg’s work in a way that so clearly seemed to go against the composer’s wishes and intentions?

In his famous essay The Relationship to the Text, Schönberg wrote that he had no idea what happened in the text of some Schubert songs despite knowing them well.18 About his own vocal compositions, he claimed “[…] inspired by the sound of the first words of the text, I had composed many of my songs straight through to the end without troubling myself in the slightest about the continuation of the poetic events […] It then turned out, to my greatest astonishment, that I had never done greater justice to the poet than when, guided by my first direct contact with the sound of the beginning, I divined everything that obviously had to follow this first sound with inevitability. […] So I had completely understood the Schubert songs, together with their poems, from the music alone, and the poems of Stefan George from their sound alone, with a perfection that by analysis and synthesis could hardly have been attained, but certainly not surpassed.”19

After the Berlin premiere of Opus 15 in February 1912, Schönberg wrote in his diary that the soprano’s interpretation was far too dramatic, too much out of the words instead of the music, which made some of the songs essentially incomprehensible.20 In 1913, he advised another singer in a letter about the performance of his songs: “Not too accented pronunciation of the text (“declamation”) but a musical working out of the melodic lines! – So don’t emphasize a word which is not emphasized in my melody, and no “intelligent” caesuras which arise from the text. Where a “comma” is necessary, I have already composed it”.21 In the preface to Pierrot lunaire, he wrote: “It is never the task of performers to recreate the mood and character of the individual pieces on the basis of the meaning of the words, but rather solely on the basis of the music. To the extent that the tone-painting-like rendering of the events and feelings given in the text was important to the author, it is found in the music anyway. Where the performer finds it is lacking, he should abstain from presenting something that was not intended by the author. Otherwise he would be detracting rather than adding.”22

I agree with Schönberg that it is not our subjectively added moods derived solely from the text that should guide our performance decisions. I think, however, that ignorance of the text would make the performance of vocal music meaningless as well. I decided that Schönberg is not necessarily right about everything when it comes to the performance of his music. My experience told me that an approach to Lied through the words could help me create a performance that is “alive” and that could be understood by today’s audience. I decided to consider Schönberg’s remarks not as fixed rules but as warnings against exaggerating the connections between the figurative level of the text and the music (tone-painting) and against adding artificial emotions.

Schönberg’s remarks also have to be understood both in light of how he perceived his compositional process and the performance practice of the time. In 1931, Schönberg wrote a self-analysis of his compositional process for psychologist Julius Bahle, in which he described several composing stages with only the last one being the thorough drafting of the composition. One might refer his comments from The Relationship to the Text to this final stage.23 The performance practice of vocal music at the time was influenced by Wagner, who wanted his opera texts to be understood. Friedrich Schmitt established a new school of German singing, training singers from the viewpoint of speech. Gradually, the declamation of texts became natural in singing and went towards what would later be regarded as exaggerated and tasteless.24 Schönberg referred to this performance practice in singing in an essay from 1926: “Think how, in the days when Wagner was new, singers used to declaim rather than sing, whereas now everyone tries even in Wagner to fulfil the demands of bel canto.”25 He also slightly amended his earlier statements on the insignificance of text in his 1949 essay This is my Fault, where he wrote that vocal music would not exist if the music would not heighten the expression of the text.26 And already in his 1932 lecture about the Orchestral Songs Op. 22, he said, “if a performer speaks of a passionate sea in a different tone of voice than he might use for a calm sea, my music does nothing else than to provide him with an opportunity to do so, and to support him.”27

The gap between Schönberg’s and my view on the role of text in the performance of vocal music turned out not to be as huge as I thought it was when I started the project. He might have thought it the lesser of two evils when he asked to ignore the text rather than to overemphasise it. Throughout the project, I realised on many different levels, be it the relationship between poetry and music, the give and take between the singer and me, or the negotiation between tradition and originality, that it is crucial to scrutinise automatisms and preconceptions and to discover the right balance anew every time in every context. I still believe it is important for me to know what the composer wants from the performer so that I can make informed decisions. However, I must not be afraid to respectfully disagree with him when my experience as a performer tells me to do so. I decided that starting with the words was worth a try.

Playing Lieder with Texts by Stefan George - Contextualisation I

Kerrigan, who explored Opus 15 from the singer’s perspective, wrote that it is essential for the performers to understand the artistic movements of the time and to know about the work and life of Stefan George. Even for native German speakers, his poetry is difficult to comprehend.28 I agree with her assessment and found it helpful to learn more about George’s work to get “behind” the poetry to the third level of the text I described above. Finding out more about George and his way of writing also felt like building up a more personal relationship to the material. Insights into the background of a poet or composer can help to shed a light on the genesis of a work and thus lead to an interpretation that carries conviction. I believe that, although this kind of knowledge is not directly transferred to the audience, the performer’s intoxication and euphoria of feeling a deeper connection to the work and its author will be perceived by them. I also found that this affective bond seemed to influence my memory positively, as I was able to recall the poetry after a surprisingly short time.

George claimed to renew poetry. His early works were influenced by French symbolists according to whom poetry should have an autonomous value. Poems should evoke aesthetic truths rather than describe them directly. George translated the slogan “L’art pour l’art” (Art for art’s sake) and adopted it for his literary programme.29 Sound and form guide the order and choice of words in George's poems, and the resulting complicated sentence structures and certain vagueness make them often difficult to understand. George’s friend, the graphic artist Melchior Lechter reported about the genesis of Traurige Tänze (Mournful Dances), a collection of poems in Das Jahr der Seele, from which Webern took the text to one of his songs Op. 4: “For days he hummed melodies for the Mournful Dances for himself, which were often quite simple. First then, a poem emerged. Thus, for him, a rhythmic sound preceded the poem. Because I heard these melodies at that time, I can read out aloud these poems the best.”30

George’s spelling was also influenced by his aural perception of poetry. As there is no difference in pronunciation, George did not use capital letters apart from marking the start of a sentence or verse, both in his correspondence and in his poetry.31 He also tried to convey the exact sound of words by removing unnecessary consonants.32 He used a particular handwriting in manuscripts from 1897 and special fonts for printed editions from about 1904.33 This individual style of both orthography and typography made his poems, on the one hand, appear very exclusive and unique, but it was also supposed to convey simplicity. The reader should concentrate entirely on the recitation without being distracted by unnecessary signs. Moreover, George intended to make silent reading and immediate understanding more challenging, as to him, poetry was supposed to be recited like music should be performed and not just studied in a score. The listener of these recitations was not meant to search for the poem’s content and rather just experience the impact of the performance, the magic power of the sound of the not yet understood word.34 To give the audience an experience of this aspect of the poetry, I used a redesign of George’s font in the program to the first concert. George’s own recitations were described as extremely expressive, but without pathos, quivering from emotion and yet hard and resounding. He read as if the poem was a magic incantation. His voice changed its pitch only rarely and was then kept strictly almost as if singing a single note. He did not change it at the end of a poem either, so the poem appeared to be without start and end as if it were a part of something bigger.35

Considering the nature and genesis of George’s poems, Schönberg’s claim he understood them from the sound alone made much more sense to me. I thought a performance of Opus 15 might benefit from us trying to convey the poems’ ambiguity and keeping the multilayeredness instead of presenting it in a one-dimensional way and smoothing out the difficulties to make it easier to understand. However, I had to realise that “hypnotising” the listeners the way George did is not something that works for today’s audience. For several reasons, among them this “inspiration” to keep the interpretation deliberately ambiguous, I felt we did not really reach the audience in the first concert. The performance became somewhat stiff, intellectual and boring, which is the reason why I started to think more about reception, my relationship to the audience and what I could do to make them see the beauty and richness of this repertoire. I realised that an audience of non-German speakers requires a different kind of communication during a performance than an audience of German speakers.

When I started my project, I decided to contextualise Opus 15 with other Lieder with texts by George to explore if there is a particular “performative feel” to songs with his poetry. Although works by other poets were more popular at the time, like Richard Dehmel’s poems that had been set to music in over 550 Lieder by 1913,36 both contemporary and later composers turned to George’s writings. From the many possibilities of settings of George’s poetry, I chose Lieder by Conrad Ansorge and Anton von Webern, as both of them have connections to Schönberg. As a result of my project, Ansorge’s Opus 14 might have been performed for the first time in Norway. Schönberg knew at least parts of Ansorge’s George-Lieder as they were presented together with some of his own works in a concert in February 1904.37 They might have inspired him to write his Opp. 14 and 15 to poems by George. Schönberg’s George-Lieder in turn probably inspired his student Anton von Webern to write his settings of George’s poetry in 1908 and 1909.

First, I explored all texts independently from the music, starting with the poems of Opus 15. I assumed that if I first read the poems on their own, my understanding of them would not be coloured by the music. It was difficult for me not to start practising or even to look at the music, but I wanted it to have minimal influence on my view of the text during this time. I thought this way I might later discover if the composer understood the poem differently, and I might be able to observe which aspects of a text were important to him. I worked with the original poems for all the repertoire of this project, as sometimes a composer selects just a few stanzas out of a larger work, or makes changes to the original.I also decided to study the poems more in-depth than I had done in my previous work with Lieder. One could assume that knowing the meaning of each word and how it is pronounced would be enough, but I thought that a more profound analysis could be helpful in the process of getting a feeling for a poem and later for how it “translates into”, interacts with and is transcended by the music. I also thought this kind of work might benefit my understanding of George’s complex poetry. I reflected on how the texts were written and what about them fascinates and inspires me. I read them aloud and analysed them in detail, not for transferring the analysis directly to my work with the music but as an exercise to start thinking deeper. In the process of reflecting on the poems, I unintentionally learned them by heart. This benefitted my work with the singer as it was easier for me to anticipate what she would do. I do not enjoy making mistakes, yet a good performance involves risk-taking. Through the initial analysis of the poems, I created a “safety net” while simultaneously developing a bond to the material and making it mine.

It is incredibly satisfying to get “behind a poem”, to experience a moment when a new way of understanding suddenly opens up. Such an experience of sudden discovery creates a bond to the work. For me, the work with George’s poems resembled focusing the lens through which I saw them. First, I only had a few impressions, but during my preparation of the first concert and later as well, the poems got clearer contours, richer colours and more nuances. One might think that I as a native speaker understand a German poem when I read it for the first or maybe the second time. That is true to a certain extent, but there is always something left to discover, which makes the work with poetry and music so interesting. I got fascinated by how closely form and image work together in George’s poetry and how strict the poetical form is without appearing overconstructed. In addition, the language is extremely colourful and almost synesthetic. However, despite its expressive power, the texts did not have a particular “performative feel”. Although I perceived similarities in the poetry of the different Lieder I worked with towards the first concert, the first contextualisation did not seem to help me much as a performer.

The peculiarities of George’s writing became more obvious to me when I played Opus 15 in the context of Lieder with other poetry. In the first concert, it seemed like the effect of each of the poems was overshadowed by the context of the others. For this reason, among several others, on which I will elaborate in "Turning Point Reception", the first performance of Opus 15 felt rather heavy and long. Despite the affective bond created by my intense involvement with the poetry, I was not able to “translate” my new understanding of and love for the texts as well as in the later concerts due to my unfamiliarity with Schönberg’s and Webern’s sound worlds. I nevertheless think that my later performances benefitted immensely from the work I did before the first concert as it set in motion a process of discovery of nuances of meaning, triggered my reflections on the communication with the audience and led to a constant re-evaluation of the balance between text and music, in which the words surprisingly got more space when the focus was no longer on them. Therefore, I think that approaching Opus 15 through the poetry did not only work, albeit only in the long run, but was essential for the more successful later performances. Schönberg’s views became a concern for me once again in the final few months of the project when I started to wonder if our interpretation got too declamatory. The next time I perform the work, I will have to evaluate anew if the balance between words and music works.

In hindsight, I think I might have gotten more out of this contextualisation of Opus 15 with other George-Lieder at a later stage of the project. As understanding the text is my first working step anyway, it seemed sensible to start with the text context, but I had not considered that I might not immediately understand the music or that it might take a lot of energy to sort out collaboration issues due to the complexity of Opus 15. Despite being able to read and learn most of the repertoire rather fast, I needed time to hear and understand it better, and I lacked the experience of having performed Opus 15 once. Perhaps my background of working as a collaborative pianist had blinded me to the true difficulties of this repertoire. I often have to learn music fast, and occasionally I have to play repertoire I am less comfortable with, but I am used to disregarding my discomfort for the sake of making it work. During a performance, there is no space for doubt, so it is sometimes easier to ignore difficulties.

“There is only one question: do you sing it in the original German, or in English? I am most fond of having it presented in English, so that the audience can understand really every word without being distracted by looking at an extract in the printed program.”38 Schönberg’s question to Rose Bampton, who sang Opus 15 in New York in December 1949, appears strange in the context of his statements in The Relationship to the Text and the importance of sound in George’s poetry. Schönberg acknowledged the audience’s need to follow and understand the text as he named the sung and the printed translations as the only alternatives. He wanted the audience’s complete attention on the music and did not seem to realise that a translation of the poems would change the whole work. Bampton performed Opus 15 in the original German version39 as most performers do. However, in one of the earliest recordings of the work, a French radio broadcast from 1949, the cycle was sung in a French translation.40 Although it is difficult to imagine, a singable translation might not be such an “impossible idea”41 if the translation is well written. It might be a rewarding topic for further research on the performance of Opus 15 to explore how different languages affect the performers’ understanding and shaping of the work.

As my language skills are not sufficient to write good singable translations, I decided to perform Opus 15 in German but to give the audience written translations of the poetry in Norwegian and English. Although it might take away some of the attention from the music and even disturb the performance occasionally through noisy page turning, I found I could create a connection to the audience through these translations. Translating the poems into English and Norwegian was, on the one hand, a challenge. On the other hand, it gave me the opportunity to get even deeper into the poetry through my recreation of it. I reflected on what makes a good translation. How close should it be to the original? For the rehearsal with my first singer, who is Swedish but lives in Norway, I had to know each word’s possible meaning. For the audience, I wanted to create a translation that makes sense and is consistent without losing too many aspects of the original. I think that the way the text is presented to the audience influences the way they perceive the performance. I quickly gave up on the idea to transfer the original sound. Even though it is crucial in George’s poetry, I figured that aspects of sound could be perceived from the original poem and I did not think my translating skills would be sufficient to include sound features in a meaningful way. I do not believe it is possible to translate all the ways in which a poem affects a listener. Therefore, I concentrated on translating images and meaning. I tried to stay close to the word order of the original poems when that made sense so that the audience would experience my translations like subtitles in a film. For my second concert, I kept the English translations of Opus 15 almost entirely, but changed some elements in the Norwegian translations, going further away from a more literal translation towards a more poetic tone and a less complicated rendering. Although I used the same translation in the programs of the second, third and final concert, this translation is not necessarily definitive. One of the mistakes I see many non-native speakers, especially younger students, make, is that they assume there is nothing more to a poem than what the translation conveys.

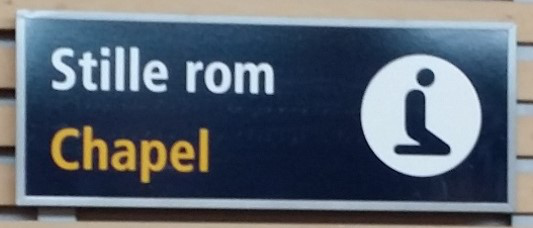

Figure 3: Sign at Oslo Airport, Gardermoen (21.09.2015).

Language is rooted in culture as these images of signs in two languages illustrate. Each word has a history, and its meaning depends on the context. I have to know which word is appropriate to decide if the word “utgang” means “exit” or “gate”. The word “chapel” in the third example seems to have a much more religious meaning than “stille rom” – “quiet room”. Each word has a certain range of meanings that is not identical with the range of meanings of one possible translation. This makes it particularly challenging to translate poetry, where nuances and the way in which something is expressed are important. When dealing with words that are ambiguous in the original, I often had to decide on only one way of reading it for the translation. Play on words or figures of speech were difficult or impossible to translate at all. George used many neologisms, like “Blättergründen” in the first poem of Opus 15, and poetic words which one would not use in everyday language. Translation helped me to get closer to understanding these, as I was forced to explore their possible range of meaning. As neither English nor Norwegian are my first language, I have a limited “active vocabulary”. In my translation work, I started with preliminary sketches that I then edited repeatedly. I looked up each word in a dictionary, found possible translations, and then I looked up the meaning of the translated alternatives to find the most suitable word for each context before I discussed my solutions with native speakers. I worked with four native speakers on the Norwegian translations and was faced with four quite different opinions. These discussions, as well as reading translations by others, made me see how far the original goes, as well as where others have crossed a threshold and where I do not agree with their translation. My analysis work on these poems made me aware of much that goes on regarding sound and images, but I think translation both made me understand the poetry on an even deeper level and create another link to the audience. Of course, I do not have time to consciously think about all the aspects of the text when playing the music, but my internalised understanding of the text influences how I hear, think and feel during a performance.

Through translation, I did not only develop a deeper understanding of the poetry. My reflection on translation made me also discover parallels to my practice as a performer. Both processes consist of interpretation and recreation, of negotiating and shifting between different modes of understanding. I make something accessible to others while simultaneously adding my own voice to it. The translation shows how I experience the “original”. I start both processes with familiarising myself with what I want to translate, and even though my first attempts are not very artistic, someone who knows the original work or other translations might recognise it. The first rough sketch gets further refined, some elements are rewritten or discarded in the search for something that makes it “just right”. Both “translations” deal with a gap between being true to the “original” and making it work in the new language or mode of expression. The outcome is determined by the translator’s understanding of the original, his or her “transformative creativity” and skill in the target language. “Translating” music is in many ways similar to translating poetry. Both processes are transformative. Through the process, I gain insights I did not have before, which are not possible to obtain through analysis alone. I have to try to discover boundaries through practice. Some places might be straightforward and easy to transfer, in which case analysis might provide similar insights. Places of hermeneutic depth, however, are more difficult to translate. Here, I can choose between several solutions. Out of my understanding and intuition, there is often one that seems to fit best. There might, of course, always be one that fits even better, which I have not yet discovered. Due to the ephemeral nature of performance, the comparison between translation and my practice as a performer has its limits. Nevertheless, it was one of the stimuli during this project that gave me new ways to think about what I do in my practice. Throughout the project, I discovered preconceptions I had, differences between what I thought and said I did and what I actually did. Reflecting on translation helped me to get closer to understanding the necessity for constant reassessment of what I do in each context, getting rid of unnecessary automatisms and finding my voice as an artist.

In the next section, I describe in detail my views on each of the poems of Opus 15. I also include phonetic transcriptions and the translations that I used in the programs of the second to fourth concert.42 Through analysis and translation, I dug deeper into the poems, found new angles of understanding and discovered mistakes in my reading or ambiguities I had not thought of before. Throughout the project, I continued thinking about the texts and developing a kind of script or map of subtexts. The resulting enriched understanding led to gradually more nuanced performances. As it is easy to get blinded or stuck in a certain way of thinking when one works alone, I discussed the poetry with others, mainly my singers, and read others’ translations and discussions of it. Few translations exist, and I realised that even the good ones cannot convey everything. Kerrigan is, to my knowledge, the only author who mentions textual considerations from a performer’s perspective, but she merely gives rough descriptions of each poem in very few sentences.43 I believe therefore that my detailed texts on each of the poems can reveal new insights and convey nuances of meaning a non-native speaker might miss. The texts contain elements from the initial analyses and reflections on how my perception of the poem texts has influenced my way of shaping the music and my interaction with the singer that developed over time. While writing down these reflections, I realised that my real understanding came from the actual work, from trying to get to know every detail, not from reading what others have written. There are no shortcuts in performance. One does not necessarily need three years, but personal experience, the hearing and “grasping” of the material, needs time and is necessary for the “magic” to happen. My texts can also not adequately convey what happens during a performance when there is no time to think consciously about all the details. All the work needs to be internalised. I have a kind of “performative map”, a representation of the total that guides me but leaves room for improvisational freedom. The artistic result is never fixed, and performances, in turn, influence my view of the work and myself. Therefore, it seems strange to fix my view on Opus 15 in written form. Everything submitted to paper seems to become shallow and cannot convey the small nuances as my practice develops further.44 Once, I demonstrated some of my considerations regarding the text in a presentation during which I used prewritten notes and played excerpts of one of the songs on the piano.45 The presentation was well-received, and the audience commented they felt drawn into my practice, yet to me, it seemed as if I was lying as what I said did not seem to make sense without the singer and at that specific moment. The following section should, therefore, not be read as one unchangeable interpretation, but rather as a collection of thought fragments inspired by different moments in time that contributed to how I performed Opus 15 in the final concert.

| Original poem46 | English translation47 | Norwegian translation | |

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

Unterm schutz von dichten blättergründen48 Wo von sternen feine flocken schneien, Sachte stimmen ihre leiden künden, Fabeltiere aus den braunen schlünden Strahlen in die marmorbecken speien, Draus die kleinen bäche klagend eilen:49 Kamen kerzen das gesträuch entzünden, Weisse formen das gewässer teilen. |

Under the protection of dense leafy depths Where from stars fine flakes snow, Gentle voices tell of their suffering, Fabled creatures from brown maws Spout jets into the marble basins, Out of them, the little rivulets hasten plaintively: Candles came to ignite the shrubs, White shapes to divide the water. |

Under beskyttelsen av det tette løvdekket Hvor fra stjerner fine fnugg snør, Varsomme stemmer forkynner sine lidelser, Fabeldyr fra sine brune gap Spytter stråler inn i marmorbekkene, Hvorfra de små bekker haster klagende: Lys kom for å tenne krattet, Hvite former for å dele vannet. |

| Pronunciation | Rhyme scheme | Metre | |

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

ˈʊntɐm ʃʊts fɔn ˈdɪçtən ˈblɛtɐˌɡrʏndən voː fɔn ˈʃtɛrnən ˈfaɪ̯nə ˈflɔkən ˈʃnaɪ̯ən ˈzaχtə ˈʃtɪmən ˈiːrə ˈlaɪ̯dən ˈkʏndən ˈfaːbəlˌtiːrə aʊ̯s deːn ˈbraʊ̯nən ˈʃlʏndən ˈʃtraːlən ɪn diː ˈmarmoːɐ̯ˌbɛkən ˈʃpaɪ̯ən draʊ̯s diː ˈklaɪ̯nən ˈbɛçə ˈklaːgənt ˈaɪ̯lən ˈkaːmən ˈkɛrtsən das ɡəˈʃtrɔɪ̯ç ɛntˈtsʏndən ˈvaɪ̯sə ˈfɔrmən das ɡəˈvɛsɐ ˈtaɪ̯lən |

a b a a b c a c |

–˘–˘–˘–˘–˘ –˘–˘–˘–˘–˘ –˘–˘–˘–˘–˘ –˘–˘–˘–˘–˘ –˘–˘–˘–˘–˘ –˘–˘–˘–˘–˘ –˘–˘–˘–˘–˘ –˘–˘–˘–˘–˘ |

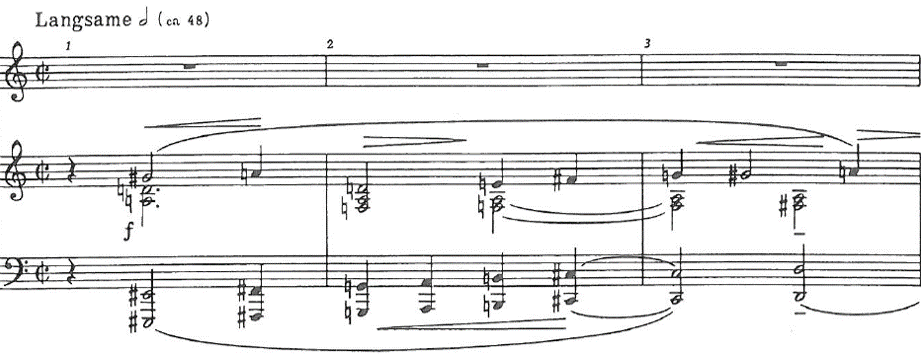

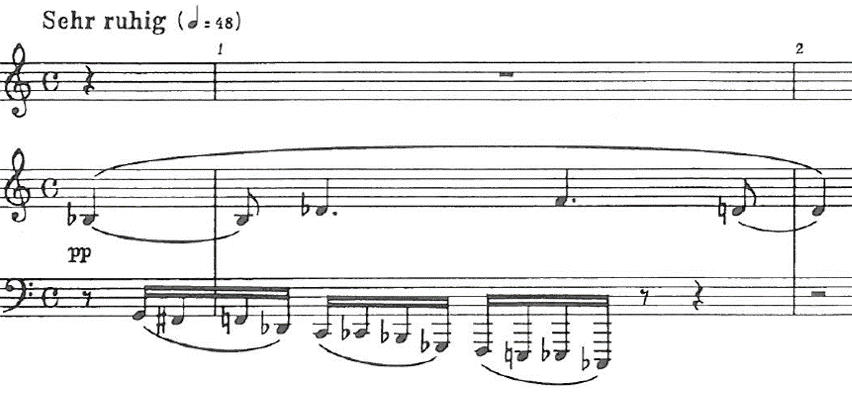

Schönberg chose 15 central poems from George’s cycle “Das Buch der hängenden Gärten” for his Opus 15. They might continue the story of the previous poems, or they could be meant as an interlude that conveys either the speaker’s memories or dreams, or an experience of someone else. The start of the cycle is exciting and mystical as it invites the listener into a still unknown landscape. The first poem describes just a scenery: Protected by leaves, there is a marble fountain or pond into which gargoyles spout water. The poem’s calm tone, the stars of the second verse, the gentle voices that tell of their suffering and allude to chirping crickets, and the candles, which lighten the bushes and might befireflies, suggest it is evening. The place seems to be devoid of people. Apart from a slightly melancholic, lonely tone, nothing hints at the speaker of the poem. Although the entire poem consists of only one sentence that describes the scenery, an arc of suspense leads towards the last two lines. Something was happening (vv. 7-8) at the place (v.1) where certain things occur at a certain though undesignated moment in time (vv. 2-6). Although this is not the first poem from George's “Das Buch der hängenden Gärten” it seems to prepare the reader or listener for what is yet to come, to create expectations and excitement as if the curtain in a theatre was rising. This is what I have in mind when I shape the piano introduction. Using the suspended rhythm, the friction between the major and minor third and the large expressive leap, I try to make it appear mystical, very soft as if far away, uncertain as if looking around but with a lot of tension.

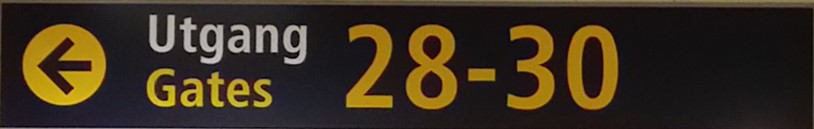

The poem is very descriptive and addresses various senses. Colourful sounds and pictures help the listener to experience the scenery: The dark vowels in “Unterm schutz von” convey warmth and protection. My single accented note in bar 8 should therefore not be too sharp, also because the singer sings softly in a low register.

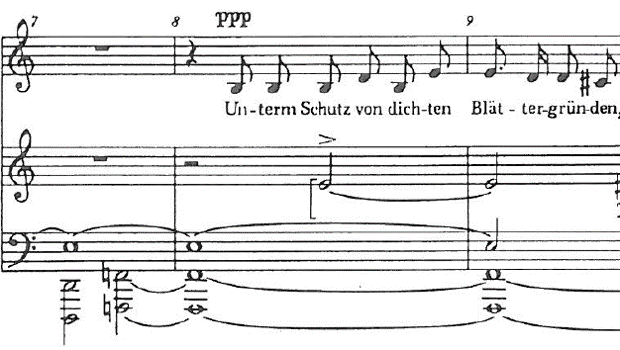

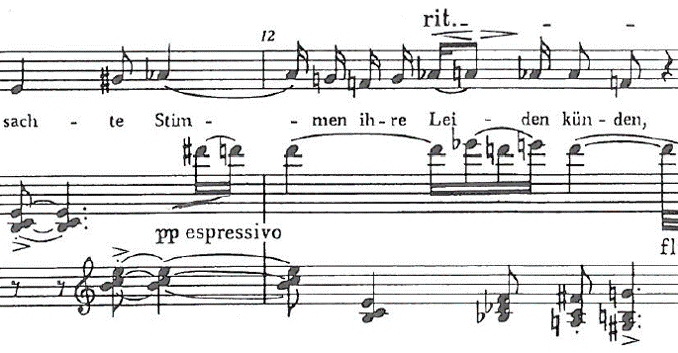

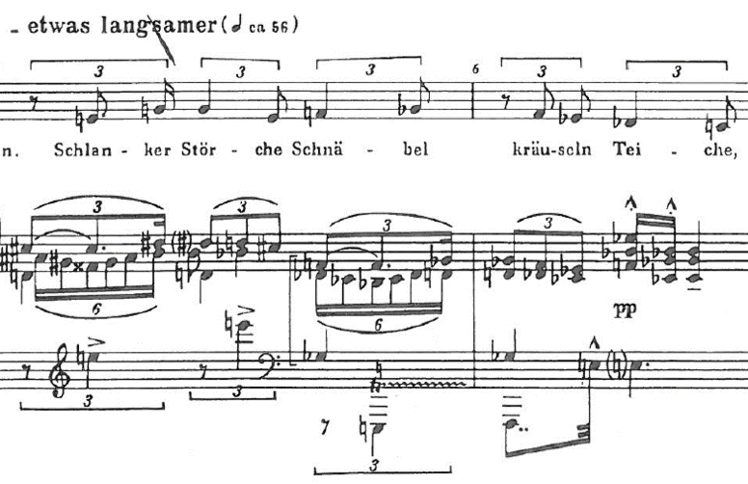

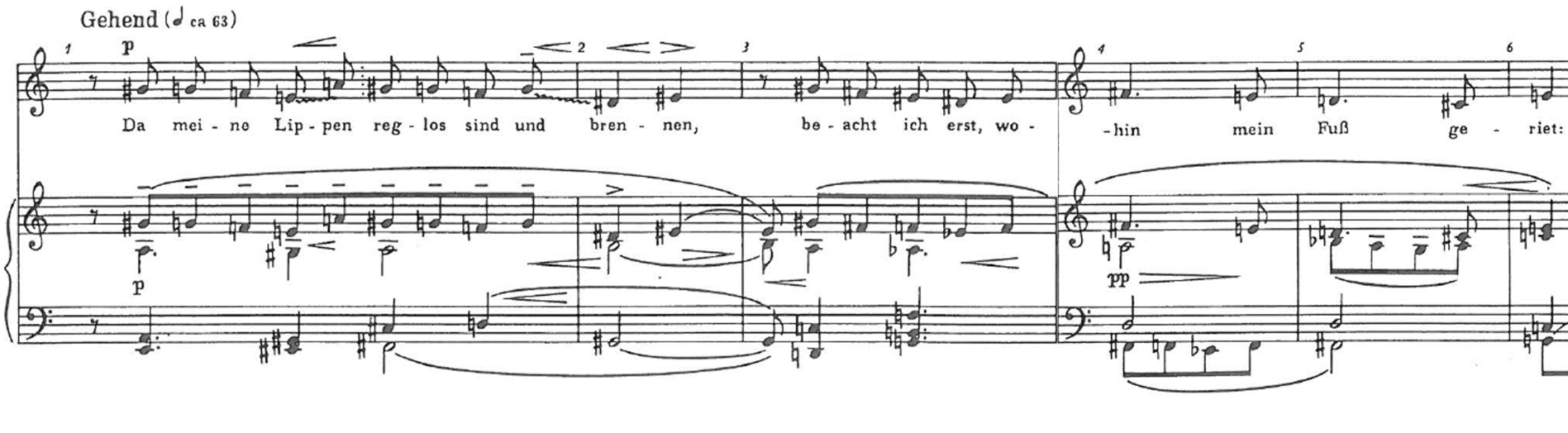

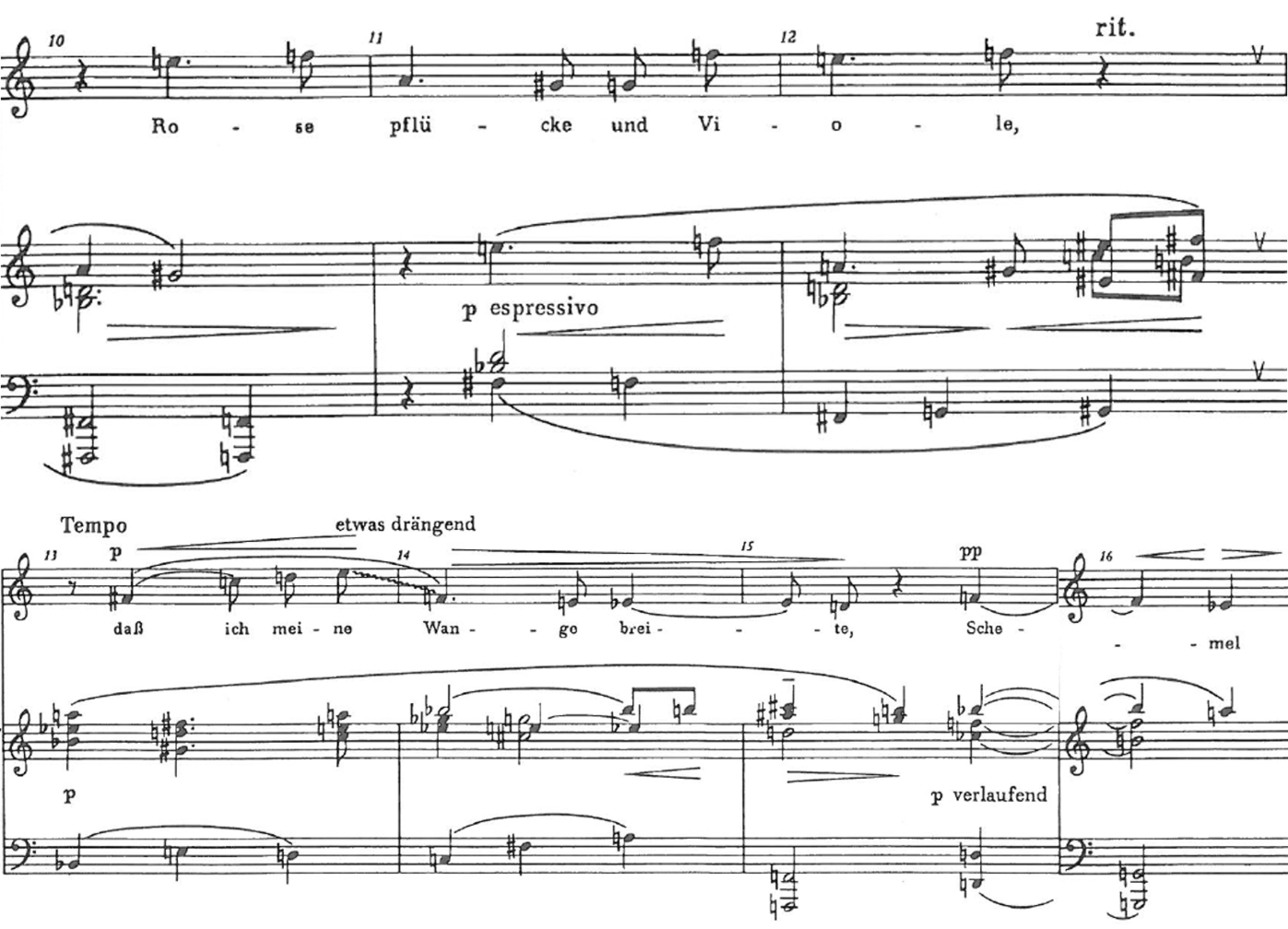

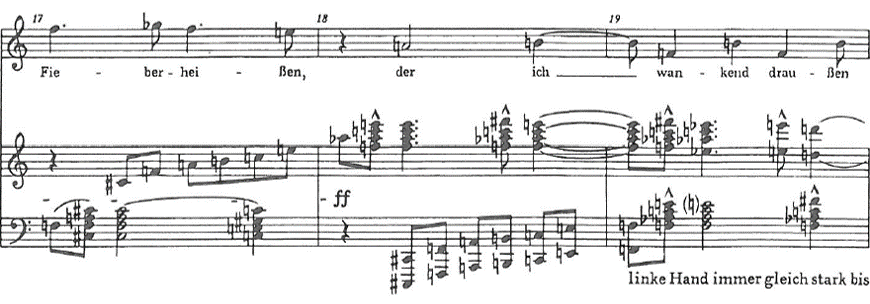

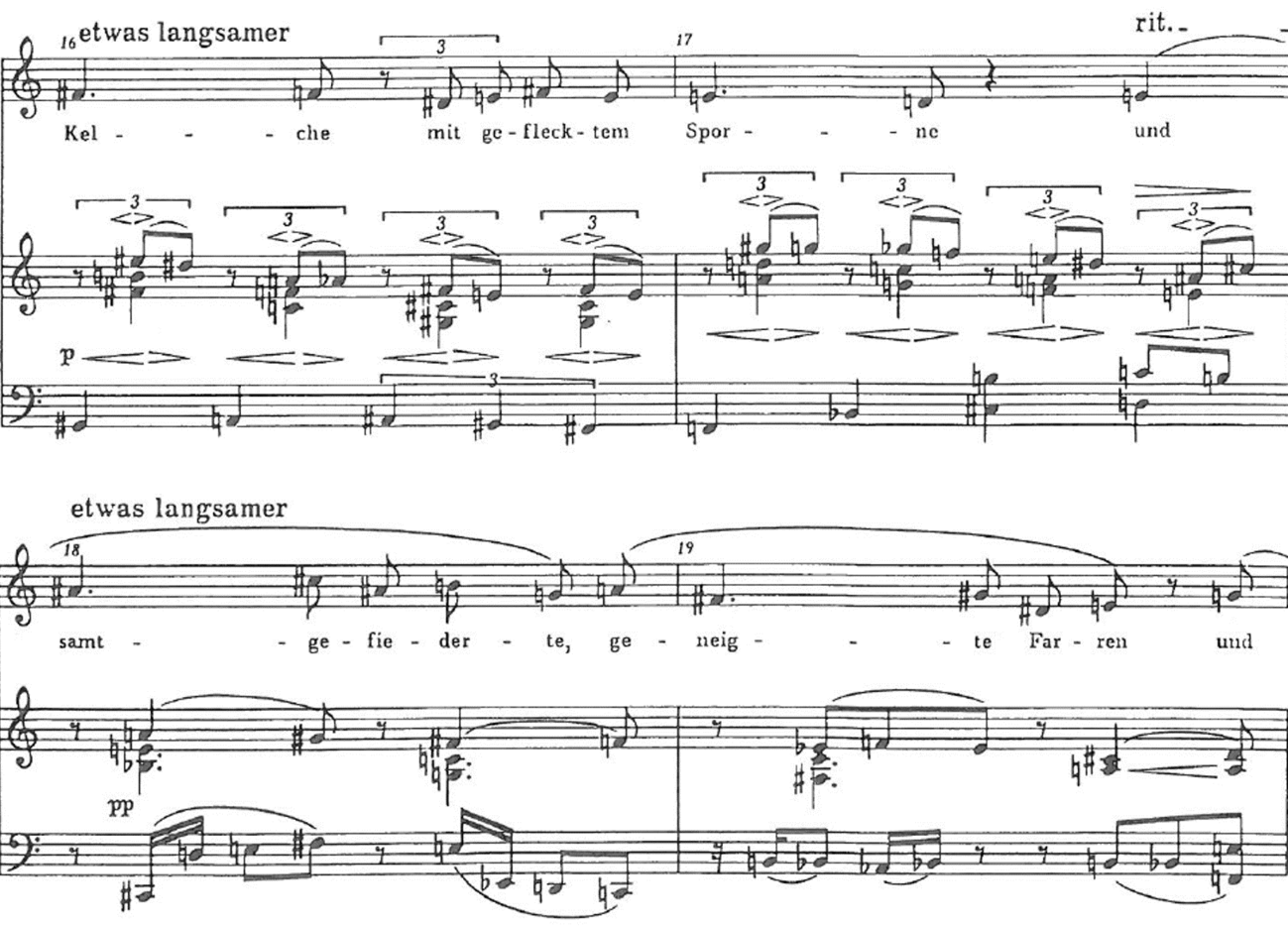

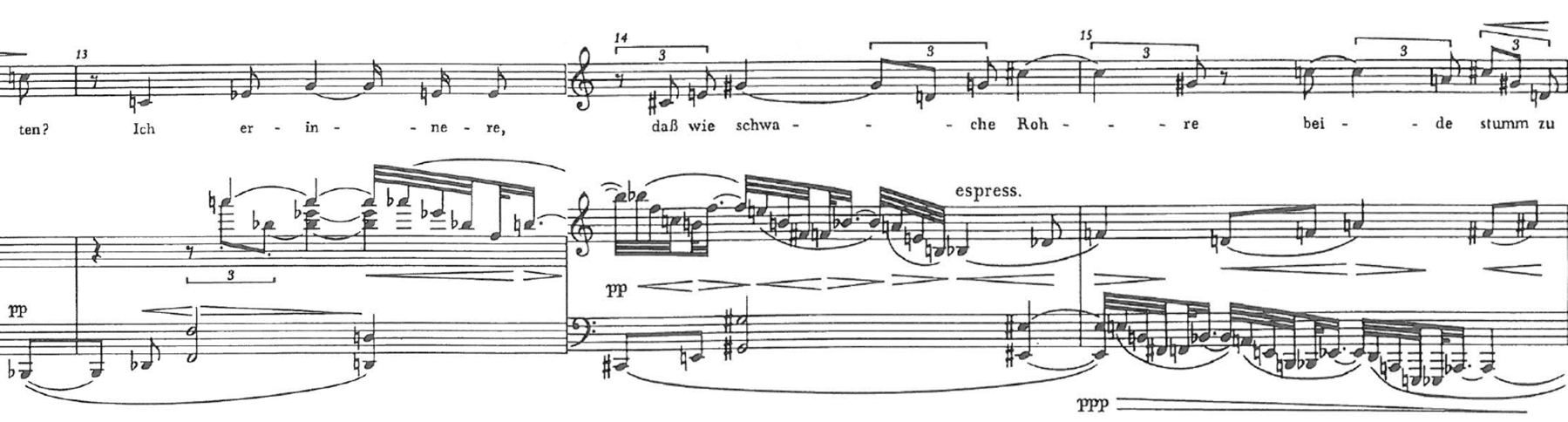

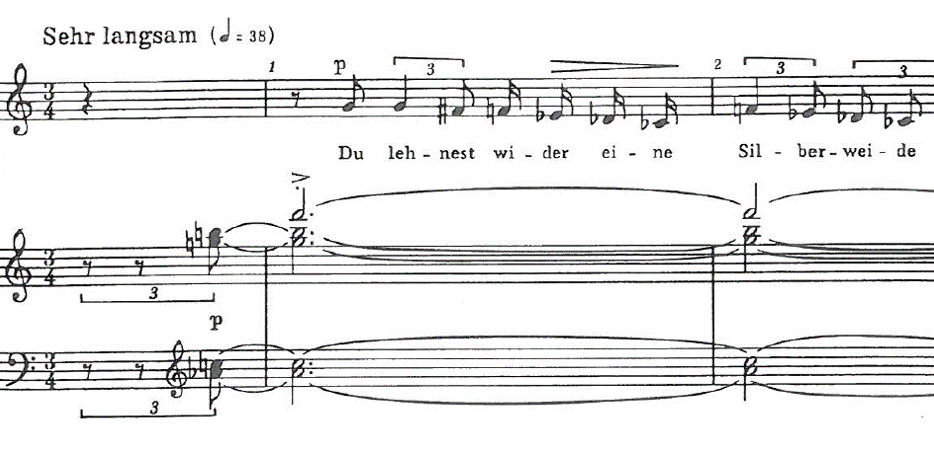

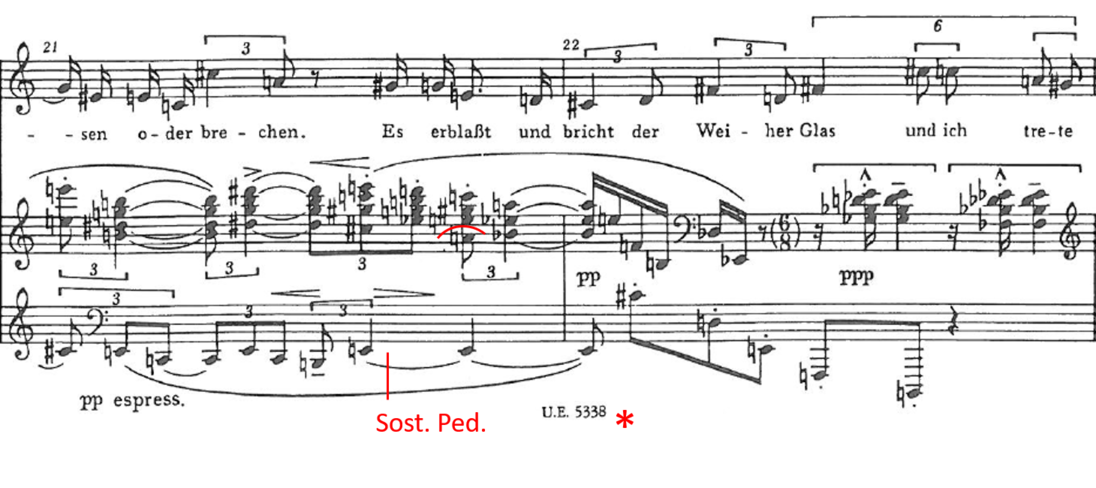

Figure 4: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. I, bars 7-9

In contrast, the light vowels of the second half of the first verse depict the leaves that are further up starting with the very light and due to the /ç/-sound rather airy “dichten” that stands out after the darks u-s and o-s of the beginning. One might even say that the colours of the vowels describe the bent-down curve of the branches, as the light vowels gradually turn into slightly darker vowels: /ɪ/, /ə/, /ɛ/, /ɐ/, /ʏ/, /ə/.50 This image is further illustrated by the falling rhythm of the word “blättergründen” which is like most German words stressed on the first syllable. “Blättergründen” is not a commonly used compound. It consists of “Blätter” meaning leaves, and “Gründe”, the plural of “Grund”, meaning ground, surface or valley. My following interjection in bar 9 should help connect the sentence and prepare for the poetic description of the second verse, which reminds of a fairy-tale and adds another feature to the scenery. Several interpretations of the verse seem plausible. Either, two images are woven into each other to illustrate the quality of the light the speaker perceives. “Flocken” (flakes) and “schneien” (snow) allude to falling snowflakes that indicate the (star) light appears and disappears in slow movements as it filters through the leaves. The verse could also depict the pollen of star-shaped flowers that drifts through the air. In either interpretation, the verse alludes to a soft movement that is also conveyed through the sound of the fricative consonants, whose effect gets enhanced by the symmetrical alliteration “sternen feine flocken schneien”. I adjust my timing as well as my touch, so it suits the image and sound of "feine Flocken". I prefer to think of it as something very soft, a little dull and thick.

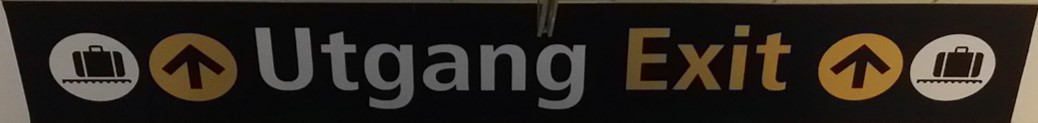

Figure 5: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. I, bars 9-11

The third verse addresses another sense: The listener is asked to imagine the sound of gentle voices proclaiming their sorrow. There is no other hint of who or what produces the sounds, but one could assume these are noises of crickets or other animals in the trees. A few fricative consonants at the beginning of the verse (sachte stimmen) convey the impression of soft, chirping noises and make the pronunciation rather slow. Despite their gentleness, the personified voices can be heard clearly in their insistent lament. The atmosphere of the entire poem is very peculiar. On the one hand, the scenery contains positive, welcoming features like the protection of the leaves. The third verse, however, adds an element of unease. Schönberg wrote very detailed instructions in the score, but they are still open to different interpretations. The chords in bar 11, marked with both accent and staccato, yet tied and sustained for the length of two quarter notes, obviously require a different touch than the accompaniment of the previous phrase. I think a fast, small and precise upward movement with half right pedal and, depending on the piano, left pedal, with good timing considering the singer’s pronunciation of the fricative consonants, fits best with these words. The chords are followed by an expressive, lamenting melody in the right hand, where I use the chromatic tension to convey the mourning voices. As the line is written in the sixth octave, it can be played very intensely without drowning the singer, as long as I am a little careful with my left hand.

Figure 6: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. I, bars 11-12

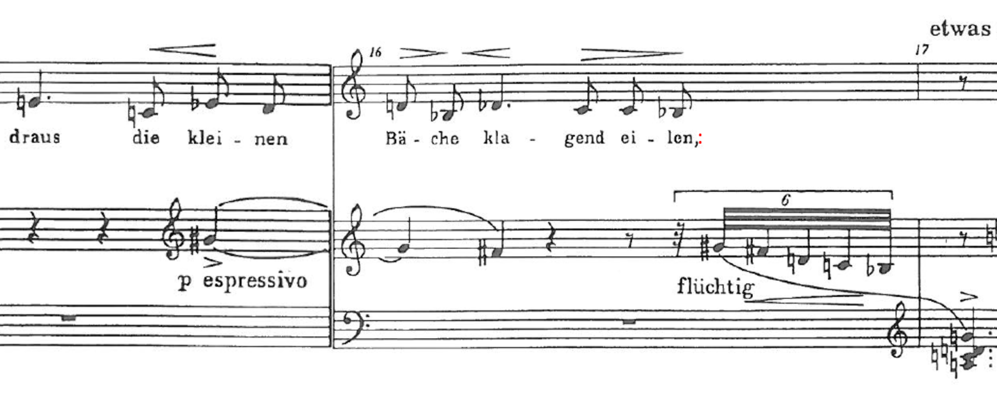

An enjambment connects the next two verses and contributes to the poem’s symmetry. It also depicts the long jets of water coming from the water spouts. The long words “Fabeltiere” and “marmorbecken” support this image. At this place, the text helps me with the phrasing, as I think ahead all the way towards the end of the fifth verse while simultaneously swelling and ebbing. I try to avoid the use of pedal to get a crisper sound that helps to convey the lively quality of the water. The gargoyles that are shaped like mythical creatures are personified and appear almost alive. The diphthong “au”, which consists of an open and a closed vowel, together with the many consonants in “braunen schlünden” makes the pronunciation of this phrase rather intricate, and conveys thus a vivid image of the big brown muzzles that needs just a fraction of time. The brown muzzles make the fountains appear a little dirty and almost decaying. The place seems a little overgrown, like a secret, forgotten entrance to the garden, that obviously has not been looked after for some time. Everything is devoid of humans and not quite as beautiful and well cared for as it was some time ago. The next verse describes the small streams of water flowing out of the marble basins. The amount of water is more modest compared to the big jets coming from the gargoyles as are the words in this verse compared to the previous verse. The gurgling sound of the water is illustrated by the alliteration of “kleinen” and “klagend”, and the personification of the streams makes the image rather vivid. The contradiction of “klagend” and “eilen” might hint at the uneven amount of water floating out of the basins. In one moment, there is a slow, “lamenting” flow of water and then suddenly more water is “rushing” over the basin's edges. I try to depict this in my playing as well by stretching the expressive falling second and giving it a very speaking sound, and playing the following notes in a very light and hasty way, as Schönberg indicates. I think the crescendo towards bar 17 should be huge, which makes it important to start softly. The text helps to make sense of the outburst: In the original poem, there is a colon instead of a comma, which leads the listener’s attention to the last two lines. Now, something is happening. Everything up to that point has to be rather soft.

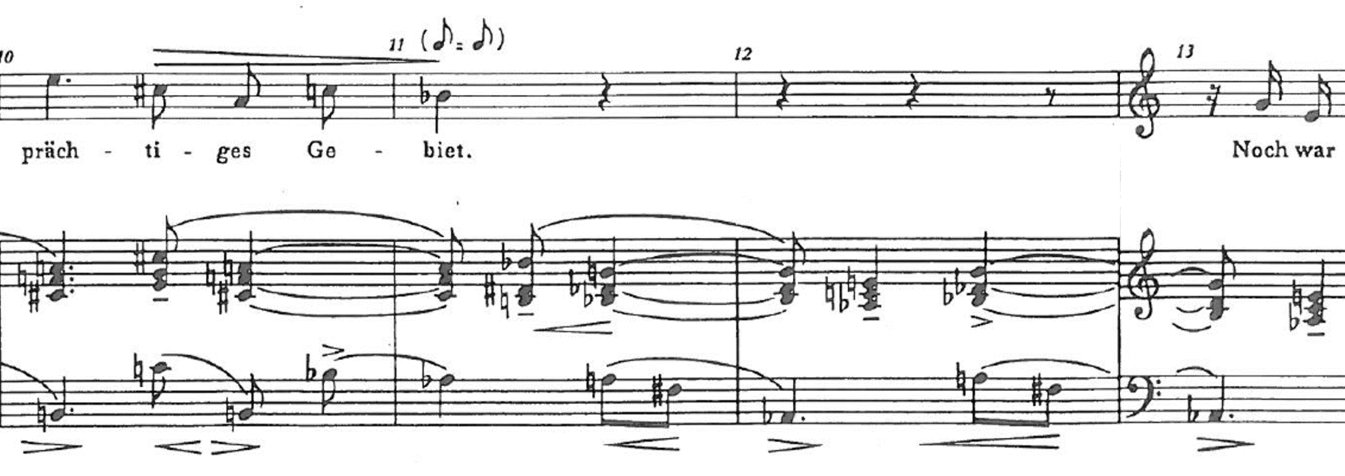

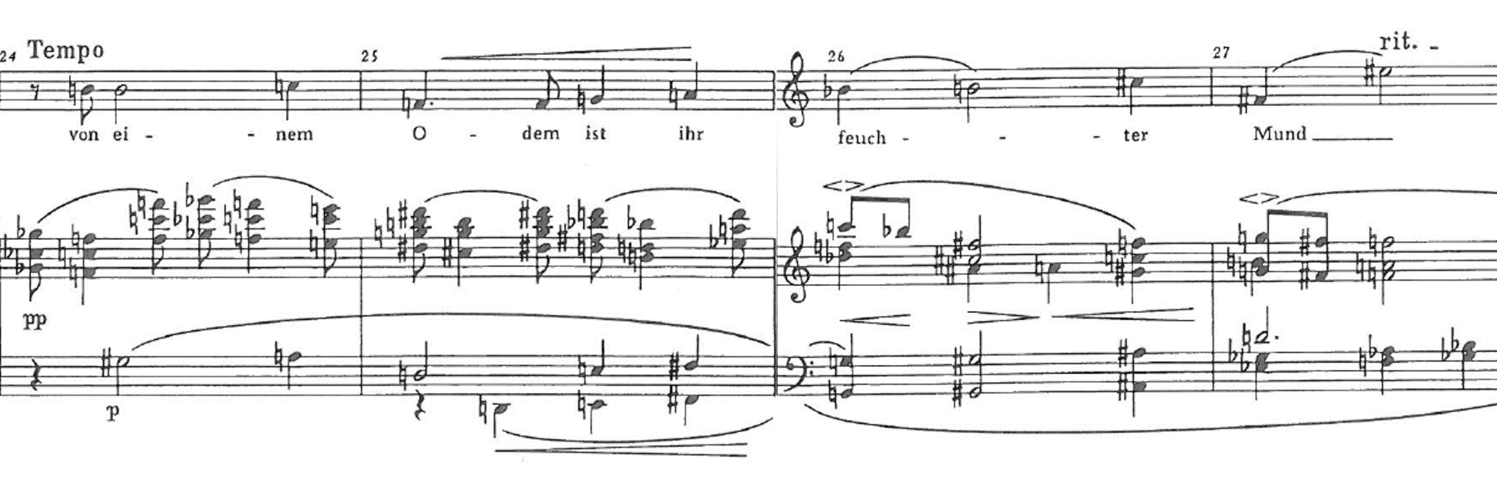

Figure 7: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. I, bars 15-17

The images of the last two verses are ambiguous again. In my view, the seventh verse alludes to fireflies that suddenly light up the bushes. The alliteration “Kamen kerzen” followed by the accumulation of fricative and stop consonants in “gesträuch entzünden” conveys the sound of buzzing insects (although fireflies do not make noises). The sound of the alliteration inspires my sound on the marcato sixteenth notes in bar 17, but at this place, I must be careful not to drown the singer with my big chords. My second singer suggested that the verse could also refer to the panicles of chestnut trees as they could be thought of as red or white flames and are colloquially called “Kerzen”. Again, the text helps with the phrasing. It is easy to lose energy after the g sharp is reached for the first time, but the tension of the poem goes towards the next verse.

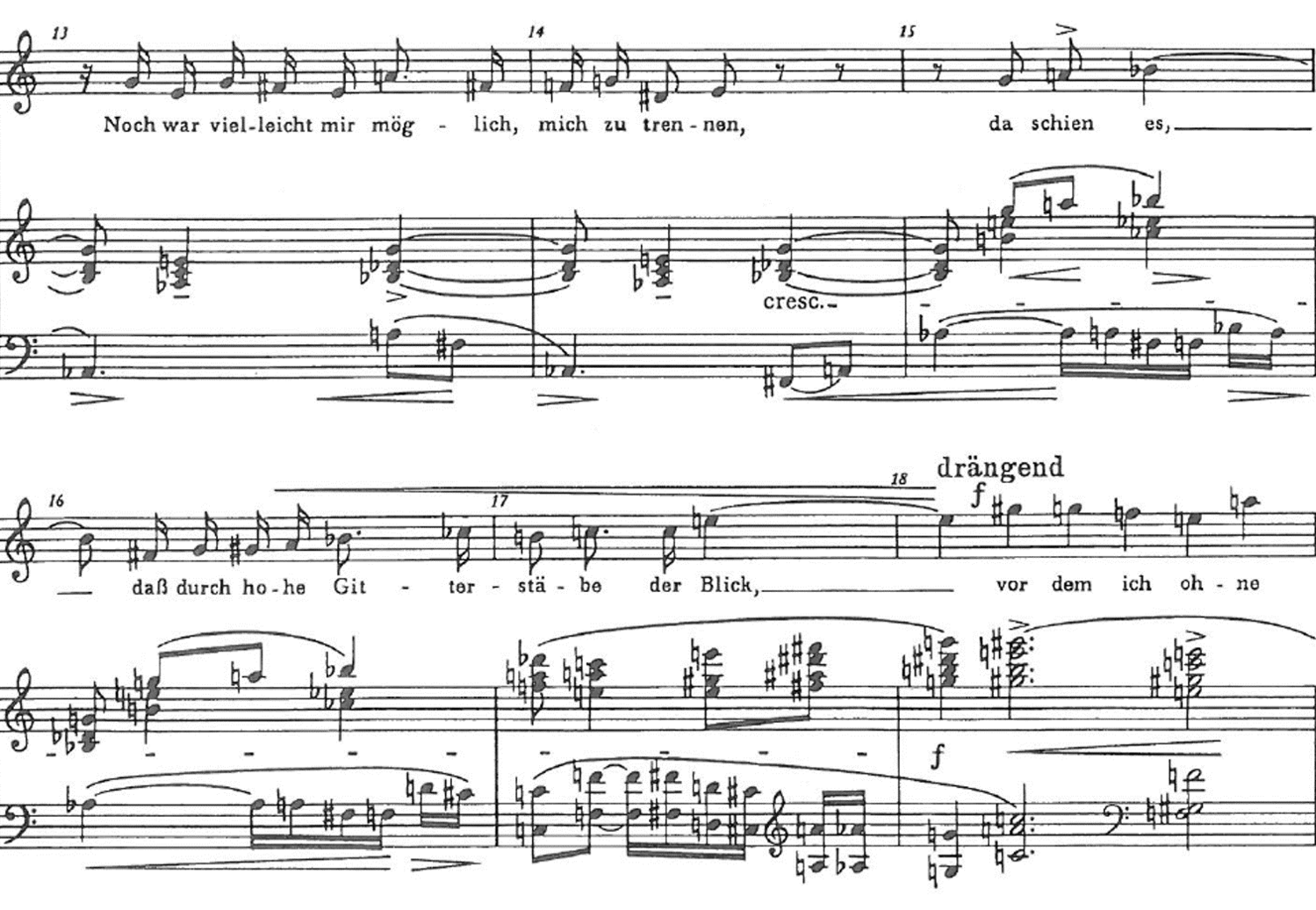

Figure 8: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. I, bars 17-19

The white shapes in the water that are described in the final verse appear even more ambiguous and mystical. They might be the reflections of the light that appeared so suddenly in the previous verse. They could also indicate a movement in the water that causes it to foam as illustrated by the fricatives /v/ and /s/, or something, for example white flowers, floats on the water. There is something foreboding about the entire poem. One can sense that it is the beginning of something that does not end well. Although the repeated motif of the falling third appears as a closing gesture in the postlude, the dramatic aspects of the text help me not to lose tension. The postlude must not convey closure but has to stay open for what is to come, like a question.

| Original poem51 | English translation52 | Norwegian translation | |

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

Hain in diesen paradiesen Wechselt ab mit blütenwiesen53 Hallen, buntbemalten fliesen. Schlanker störche schnäbel kräuseln Teiche54 die von fischen schillern, Vögel-reihen matten scheines Auf den schiefen firsten trillern Und die goldnen binsen säuseln – Doch mein traum verfolgt nur eines. |

Grove in these paradises Alternates with blossom meadows, Halls, colourfully painted tiles. The beaks of slender storks ripple Ponds that glitter with fishes, Rows of birds with dull gleam Warble on the crooked ridges And the golden rushes whisper – But my dream pursues solely one thing. |

Lund i disse paradiser Veksler med blomsterenger, Haller, fargerikt malte fliser. Nebbene til slanke storker kruser Dammer som glinser av fisker, Matt skinnende fuglerader Slår triller på de skjeve møner Og de gylne siv suser – Men min drøm forfølger kun det ene. |

| Pronunciation | Rhyme scheme | Metre | |

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

haɪ̯n ɪn ˈdiːzən paraˈdiːzən ˈvɛksəlt ap mɪt ˈblyːtənˌviːzən ˈhalən ˈbʊntbəˌmaːltən ˈfliːzən ˈʃlaŋkɐ ˈʃtœrçə ˈʃnɛːbəl ˈkrɔɪ̯zəln ˈtaɪ̯çə diː fɔn ˈfɪʃən ˈʃɪlɐn ˈføːɡəlˌraɪ̯ən ˈmatən ˈʃaɪ̯nəs aʊ̯f deːn ˈʃiːfən ˈfɪrstən ˈtrɪlɐn ʊnt diː ˈɡɔltnən ˈbɪnzən ˈzɔɪ̯zəln dɔχ maɪ̯n traʊ̯m fɛɐ̯ˈfɔlkt nuːɐ̯ ˈaɪ̯nəs |

a a a b c d c b d |

–˘–˘–˘–˘ –˘–˘–˘–˘ –˘–˘–˘–˘ –˘–˘–˘–˘ –˘–˘–˘–˘ –˘–˘–˘–˘ –˘–˘–˘–˘ –˘–˘–˘–˘ –˘–˘–˘–˘ |

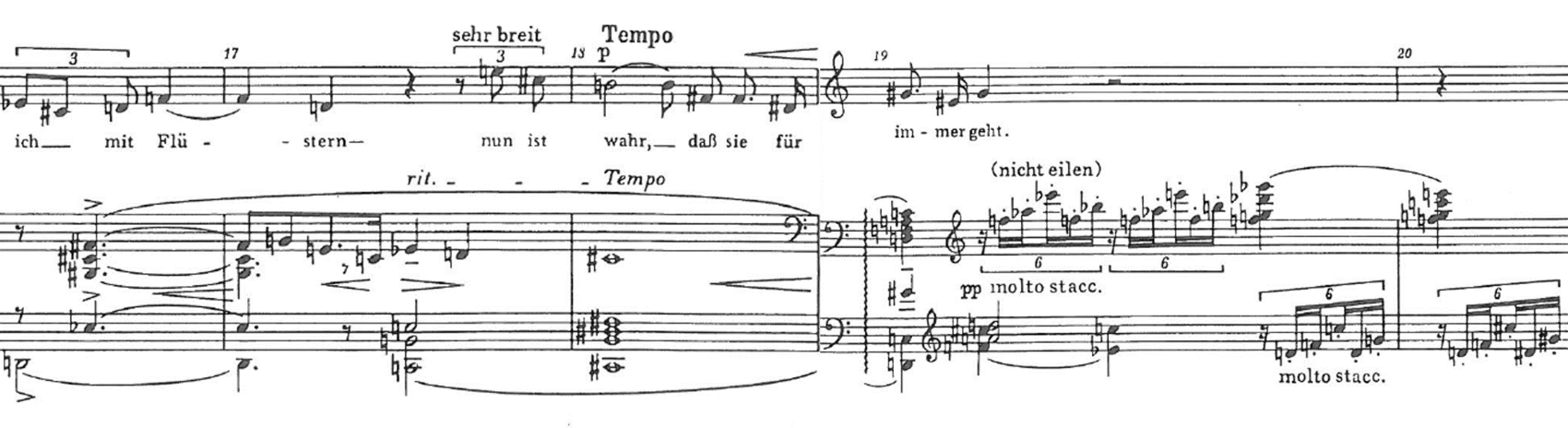

The second poem describes a new part of the landscape. The garden seems to get more beautiful and cared for towards the middle of the cycle. Both the landscape and the speaker’s feelings become more concrete. After the earthy colours of the previous text, the second poem appears brighter and more alive, and the scene is probably set at daytime. The poem contains enjambments and enumerations that create a slightly faster flow compared to the first poem.We found it necessary to take enough time between the first and second song to make room for this change of atmosphere. Despite the soft dynamics throughout, I decided to avoid the left pedal in this song to bring out the lighter colours.

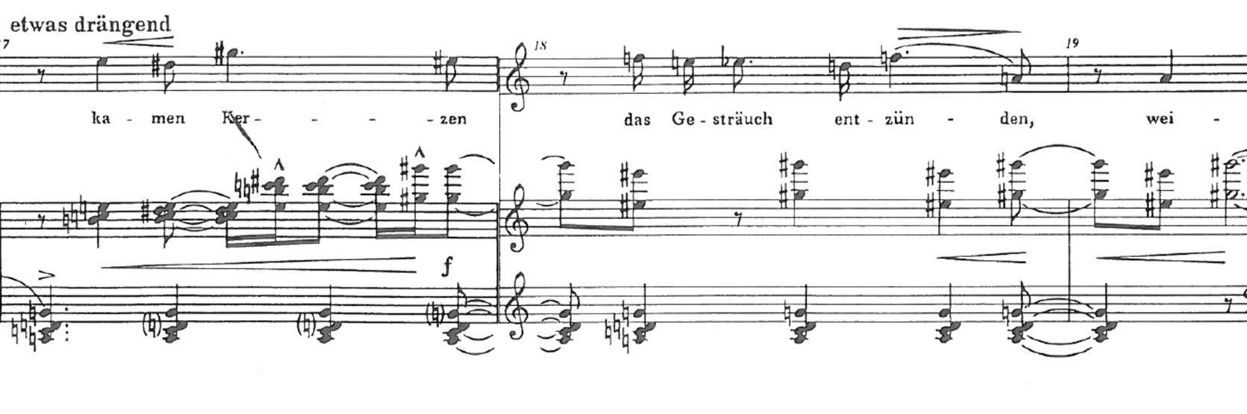

In the beginning, the speaker’s gaze wanders seemingly aimlessly over woods, flowery meadows and halls with multicoloured tiles. It seems as if his gaze is fixed on the distance before it moves to his immediate surroundings as he describes more and more artificial, human-made structures. The unusual plural “paradises” (v. 1) contributes to the impression that the area of the gardens is enormous. The speaker’s awe is conveyed through the inversion of the first sentence, which is noteworthy as it would have been easy to change the word order without losing the rhyme. I try to convey this awe through the way I play the opening arpeggio, which I think of as relaxed and sensual with a slightly heavy left hand and a slow movement that triggers the singer’s entry. Schönberg’s breath-marks in the following recitative-like phrases have occupied us a lot. It is easy to start the song to slow, getting caught up in a feeling of contemplation. Although I think that Schönberg’s tempo marking is slightly too fast, and it is important not to rush and shorten the last notes before the singer’s breath, we discovered that a sufficiently fast tempo with good breaths seems to convey the atmosphere best. When it works, it sounds as if the speaker pauses naturally to register new sensory impressions. The internal identical rhyme “diesen paradiesen” emphasises the lightness of the beginning, but the vowels get darker throughout the first three verses. In the third verse, only the rhyming word “fliesen” contains the phoneme /iː/, and the flow of the previous verses has disappeared due to the many commas. Again, there seems to be an underlying darkness and foreboding in the text. I try to listen to the slowly ascending left-hand octaves to convey this foreboding through my playing. Because of the singer’s falling line on the quadrisyllabic word “Blütenwiesen” in bar 3, I have to be careful not to accentuate the third beat despite the duration of the chord, the crescendo and the stretch that is necessary to accommodate the singer’s breath.

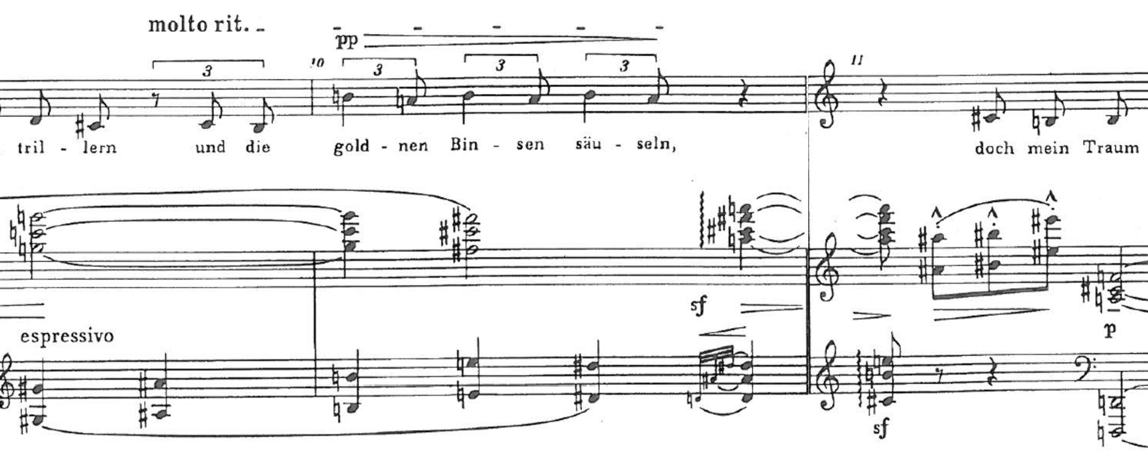

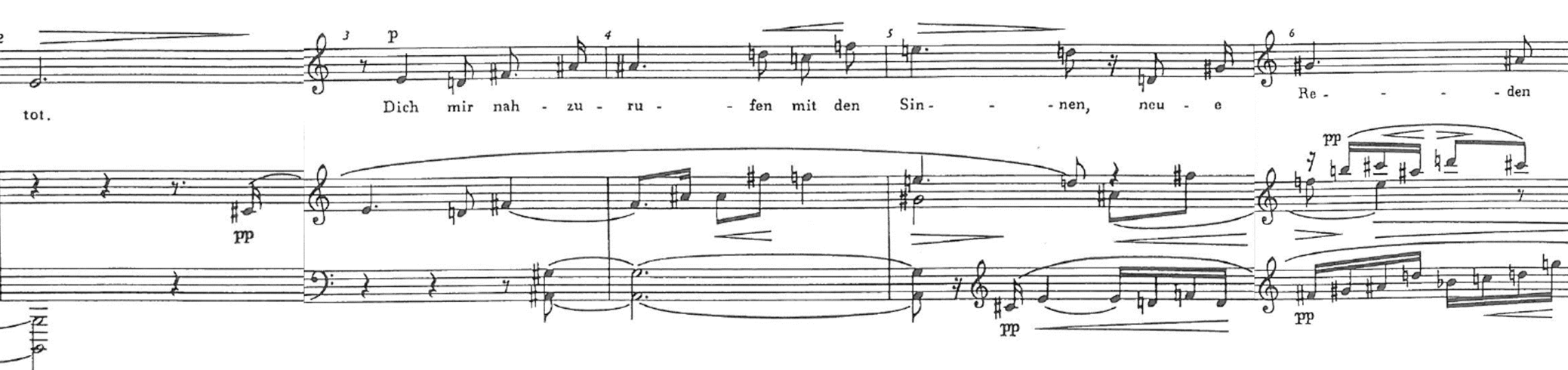

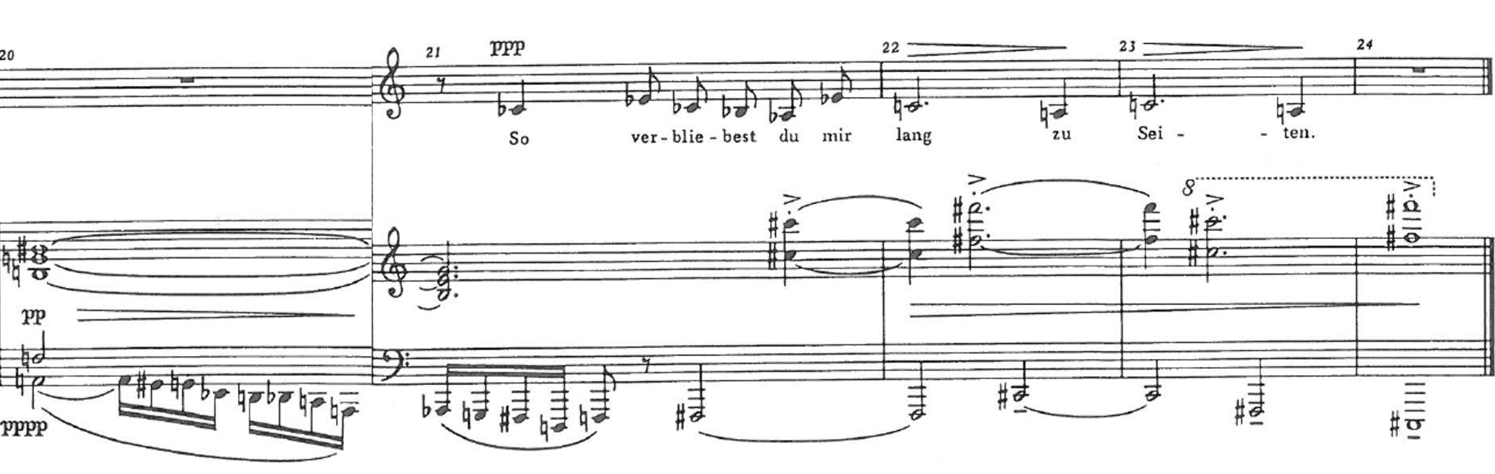

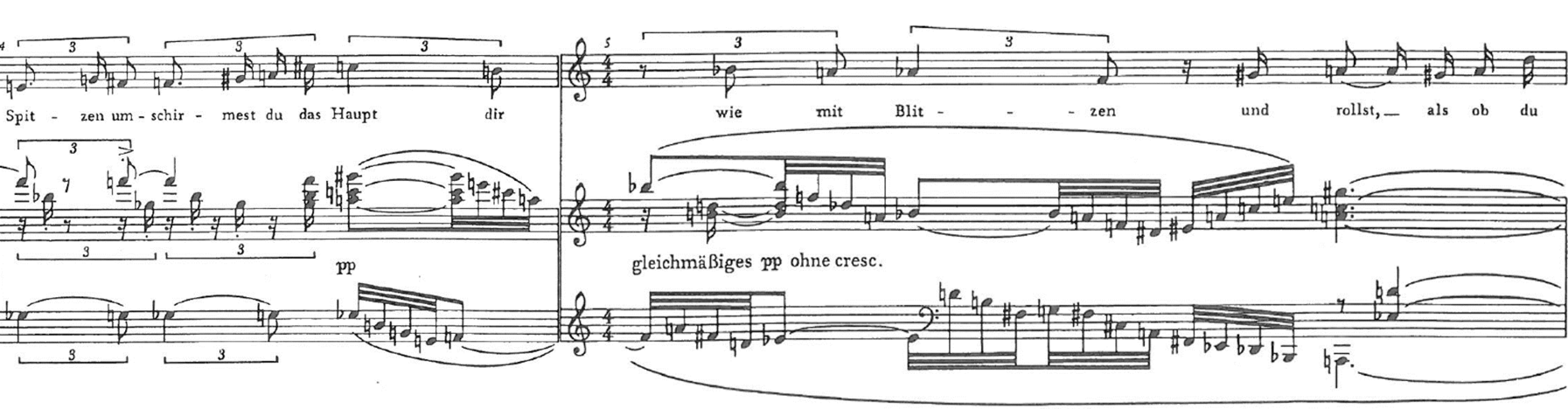

Figure 9: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. II, bars 3-4

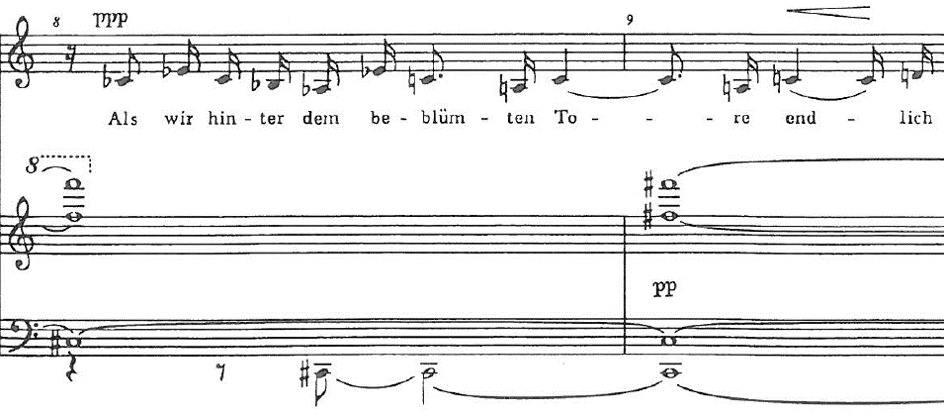

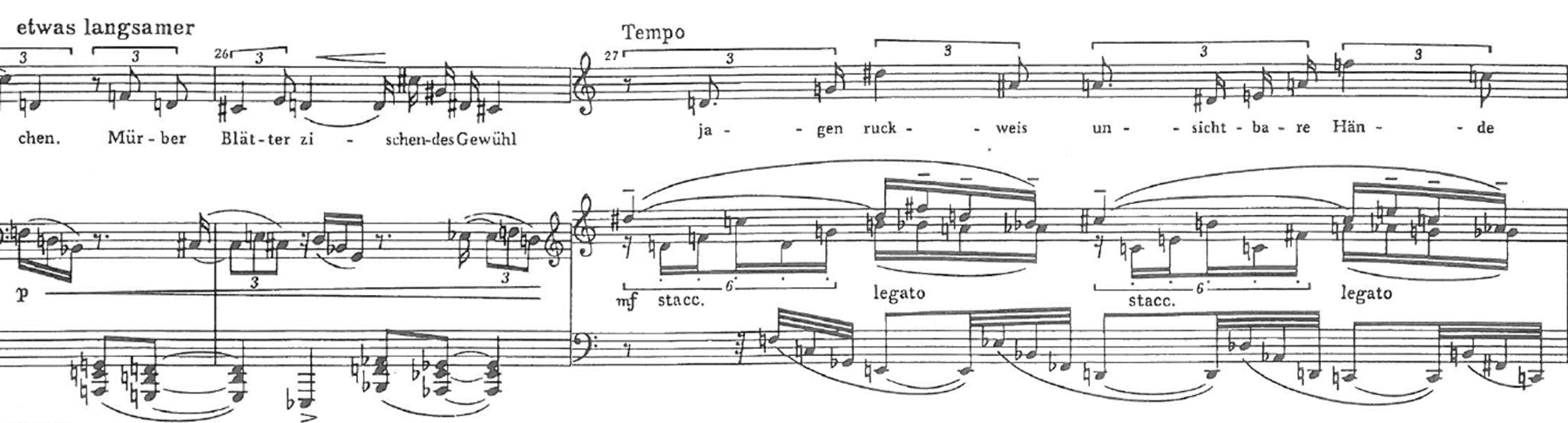

In the fourth verse of the poem, the speaker’s attention turns from the expanding landscape to his more immediate surroundings. Storks ripple the water of ponds that are full of glittering fish while rows of birds sit on the crooked ridges of the surrounding buildings. The exotic animals, the accumulation of disyllabic words and the vibrant sounds of the language, as in the play with the phonemes /ʃ/ and /ɪ/ that depicts the glittering fishes, contribute to the vividness of the scene. If the initial tempo of the song is not fast enough, the transition to bar 5 does not work. The new tempo, which Schönberg marked “etwas langsamer” (a little slower) does not feel much slower due to the smaller note values. Although the beginning of the verse might be difficult to articulate for the singer because of the alliteration “Schlanker störche schnäbel”, the atmosphere should not turn lyrical. If I feel the sextuplets as one movement, play them clearly with little pedal, bring out the accents and articulate the staccato duro well despite the pianissimo, I can convey the image of the storks’ movement and the rippling rings on the water.

Figure 10: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. II, bars 5-6

The sixth and seventh verse describe the birds that sing on the roofs. George used the word “Vögel-reihen” instead of “Vogelreihen”, which would be the correct form. It creates a certain verbal tension, at least for someone reading the poem for the first time. Because of the hyphen and the incorrect plural construction, one might read or hear “reihen” almost as a part of a reflexive verb (“birds with dull glow form a line”), which crashes with the real verb “trillern” (to warble). The oxymoron “matten scheines” (dull gleam) creates further tension. Bar 7 is challenging to coordinate with the singer, but if one keeps in mind this tension and does not rush through it, it gets easier.

The eighth verse describes golden rushes blowing in the wind. The singer can bring out the onomatopoeic quality of the word “säuseln” (to whisper), which illustrates the soft sound the rushes make in the wind and which makes the verse slightly melancholic. Because of the conjunction “Und” and the previous long clauses, one expects a continuation of the description, but the sentence is suddenly interrupted by the conjunction “Doch” (but) in the last verse. Finally, the speaker comes to the fore, declaring that his dream pursues only one thing. It seems, he can rejoice in the beauty of the garden only for short moments of time while he is obsessed with this dream. Because of the surprising change after the eighth verse, I find it important not to lose tension during the molto ritardando. I try to “sing” my expressive left-hand octaves until the end of the phrase despite the slow tempo. The following sforzato arpeggios convey the sudden change, but should not be played too harsh, rather like a friendly admonishment not to get lost in the dreamy contemplation of nature and to follow his real dream instead. I realised that I have to pedal carefully and manage the diminuendo on the octaves without losing the marcato quality. Only the chord on “Traum” should be warm and convey the speaker’s longing.

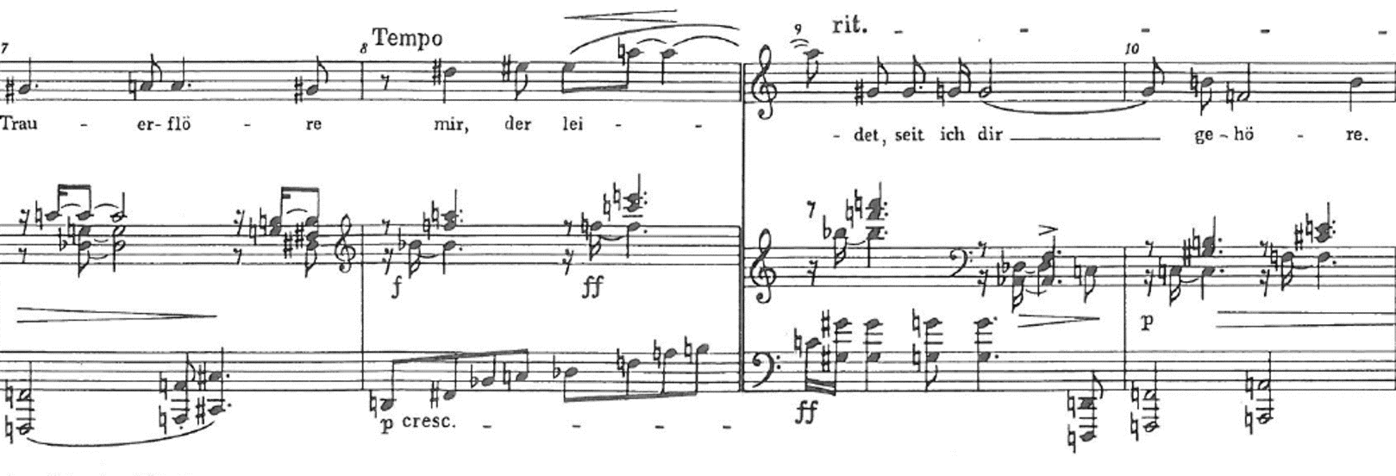

Figure 11: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. II, bars 9-11

The singer’s final note must be soft, as the word “eines” requires an unstressed second syllable. Despite the tenuto and possible difficulties in coordination, the left-hand octave at this place has to be very soft, so it does not disturb the singer’s word. In bar 13, I try to bring out the longing tenuto sound by using the left hand instead of the right. For me, this longing already has an element of destructiveness. It is on an unconscious level (the dream), but already obsessive.

| Original poem55 | English translation56 | Norwegian translation | |

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

Als neuling trat ich ein in dein gehege57 Kein staunen war vorher in meinen mienen, Kein wunsch in mir58 eh ich dich blickte59 rege, Der jungen hände faltung sieh mit huld,60 Erwähle mich zu denen61 die dir dienen62 Und schone mit erbarmender geduld Den63 der noch strauchelt auf so fremdem stege. |

As novice I stepped into your enclosure No wonder had previously shown in my faces, No wish had stirred in me before I saw you, Look with favour on the folding of young hands, Choose me to be among those that serve you And spare with merciful patience The one who still stumbles on such a foreign path. |

Som nykommer steg jeg inn i ditt hegn Ingen forbauselse var tidligere i mine miner, Intet ønske rørte seg i meg før jeg så deg, Se foldingen av de unge hendene med gunst, Velg meg til dem som tjener deg Og skån med forbarmende tålmodighet Den som fortsatt snubler på en slik fremmed sti. |

| Pronunciation | Rhyme scheme | Metre | |

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

als ˈnɔɪ̯lɪŋ traːt ɪç aɪ̯n ɪn daɪ̯n ɡəˈheːɡə kaɪ̯n ˈʃtaʊ̯nən vaːɐ̯ ˈfoːɐ̯heːɐ̯64 ɪn ˈmaɪ̯nən ˈmiːnən kaɪ̯n vʊnʃ ɪn miːɐ̯ eː ɪç dɪç ˈblɪktə ˈreːɡə deːɐ̯ ˈjʊŋən ˈhɛndə ˈfaltʊŋ ziː mɪt hʊlt ɛɐ̯ˈvɛːlə mɪç tsuː ˈdeːnən diː diːɐ̯ ˈdiːnən ʊnt ˈʃoːnə mɪt ɛɐ̯ˈbarməndɐ ɡəˈdʊlt deːn deːɐ̯ nɔχ ˈʃtraʊ̯χəlt aʊ̯f zoː ˈfrɛmdəm ˈʃteːɡə |

a b a c b c a |

˘–˘–˘–˘–˘–˘ ˘–˘–˘–˘–˘–˘ ˘–˘–˘–˘–˘–˘ ˘–˘–˘–˘–˘– ˘–˘–˘–˘–˘–˘ ˘–˘–˘–˘–˘– –˘˘–˘–˘–˘–˘ |

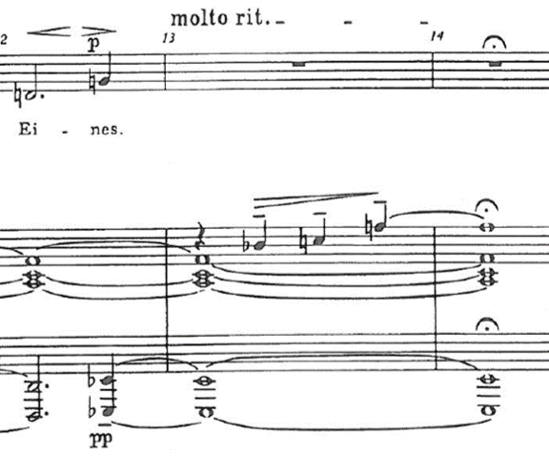

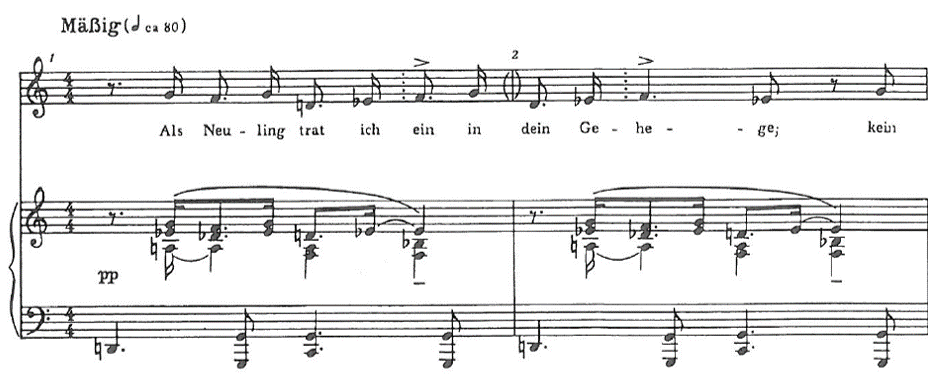

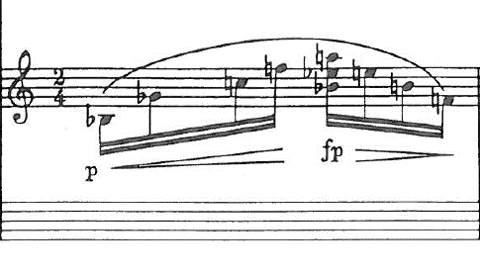

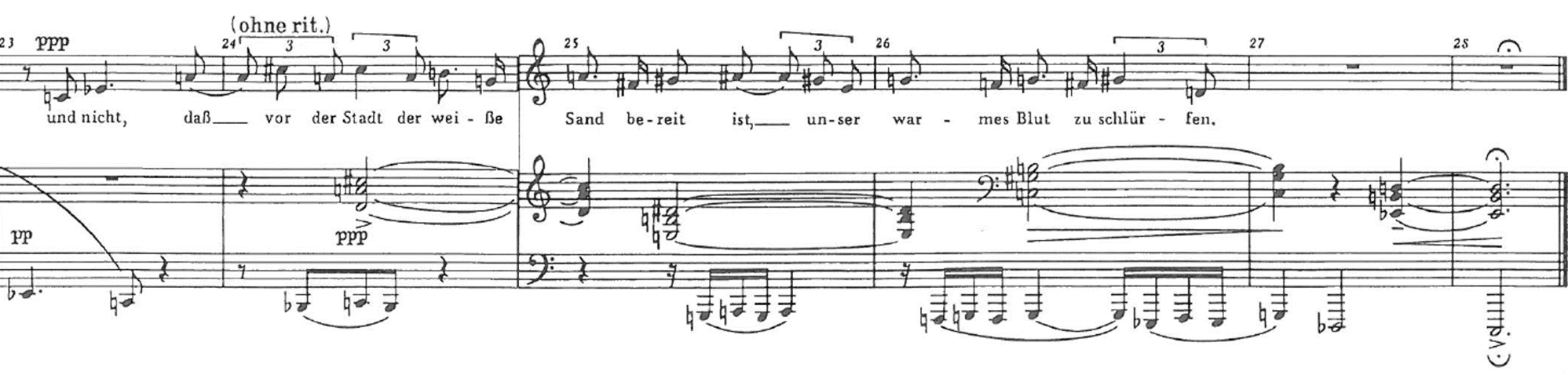

In the third poem, the speaker addresses the beloved for the first time. He has stepped into new territory and states that he had not known awe or desire before he met her. He begs her to choose him as a servant and to forgive the mistakes he is going to make. Three different images or ideas predominate the poem: a religious aspect, the concept of love as serving and the speaker’s youth and inexperience. After the trochees of the first two poems, the iambic metre of the third poem creates a sense of increased tempo. The focus has turned from a relatively calm contemplation of the scenery to the subjective experience of desire that has been transformed from the dreamlike state of the second poem to a more conscious and concrete longing. Throughout the entire song, the text helps the performers to coordinate the highly flexible tempi and dynamics that convey the intensity of emotions.

The first verse sets the atmosphere for the whole poem as the speaker humbly declares that he has come to new territory. The inversion of the first sentence is striking as it emphasises the speaker’s status as a newcomer while the pronoun “ich” (I) gets an unimportant place, unaccentuated and hidden in the middle of the sentence. The speaker describes himself with the word “Neuling”, which might either convey that he has just entered the garden and has never seen anything like it, or that he is young and inexperienced as a servant or lover. The noun “gehege” is noticeable, as it usually refers to an enclosure for animals in zoos or to an enclosed area in which game is cared for and hunted by huntsmen. The phrase “dein gehege” might allude either to the beloved’s high social rank as indicated by her ownership of such a place or to her imprisonment, the belonging to another man, which will be confirmed in the following poem. The word also implies the crossing of a border, both in the landscape and emotionally.

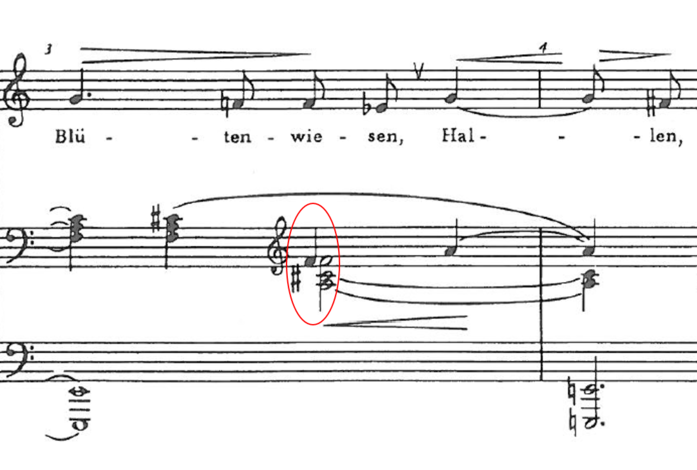

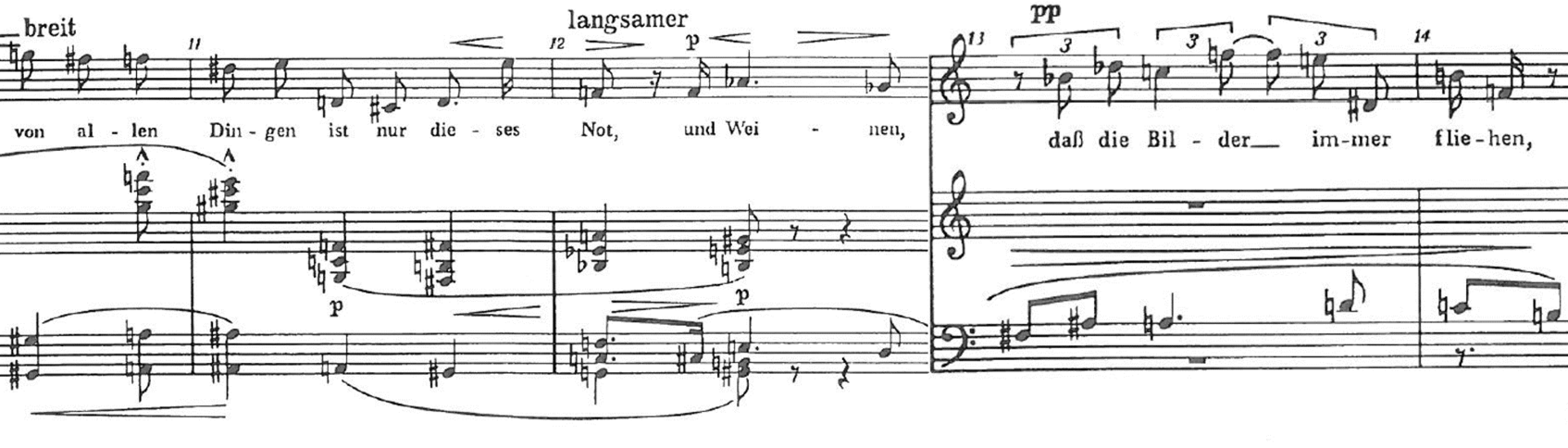

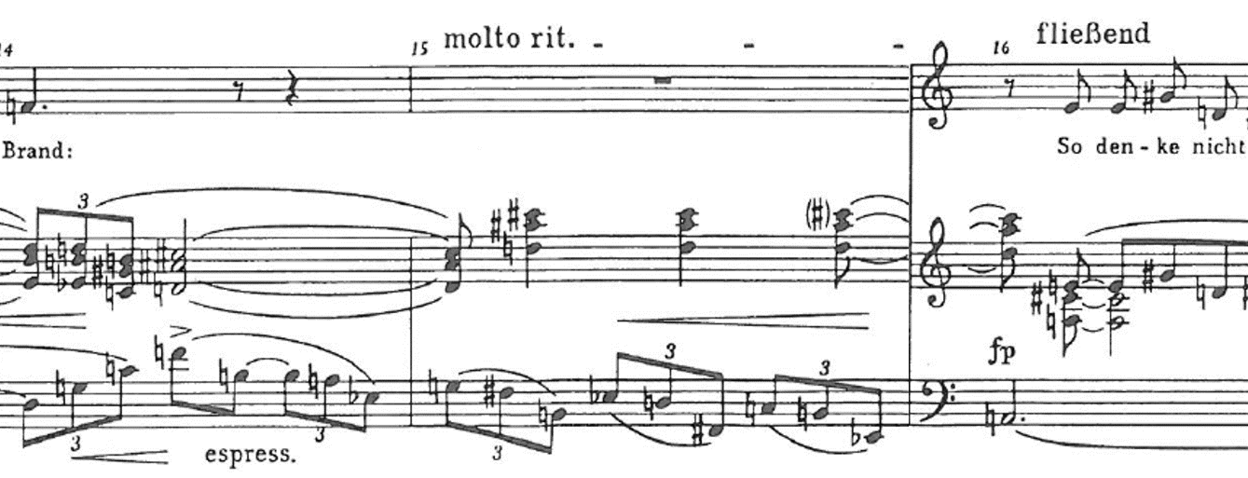

The beginning of the song can be challenging to coordinate. Due to the abrupt start and the unison rhythms, it is crucial to agree on the tempo and the quality of the dotted rhythms. The text can help both performers to find the right atmosphere. Kerrigan65 and Lessem66 point out the march-like effect of the dotted notes. My singers and I, however, tried to avoid a march-like character as it would not match the speaker’s eager uncertainty. We instead decided to play and sing more towards the accents and phrase ends instead of emphasising one and one group. The rhythmic energy tempts the performers to be too direct, but the beginning should be soft and searching yet with an underlying tension and very clear. To achieve the right kind of tension, we realised it is helpful not to take too much time after the fermata at the end of the previous song before the start of this song. It is important that the sixteenth notes are not too light, and that the singer consciously uses the consonants. I find that I can convey the speaker’s energy and eagerness on the one hand and his insecurity on the other hand by playing non-legato in the left hand and legato lines that move towards the end of each bar in the right hand. If we manage to feel this start together, the rest of the song will also work well together.

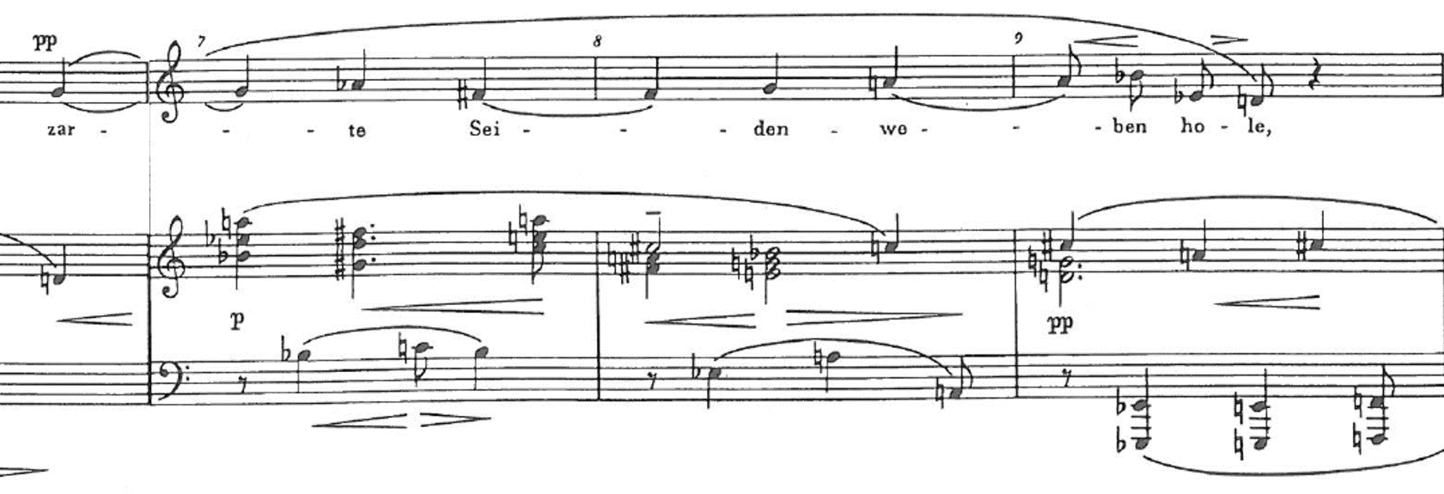

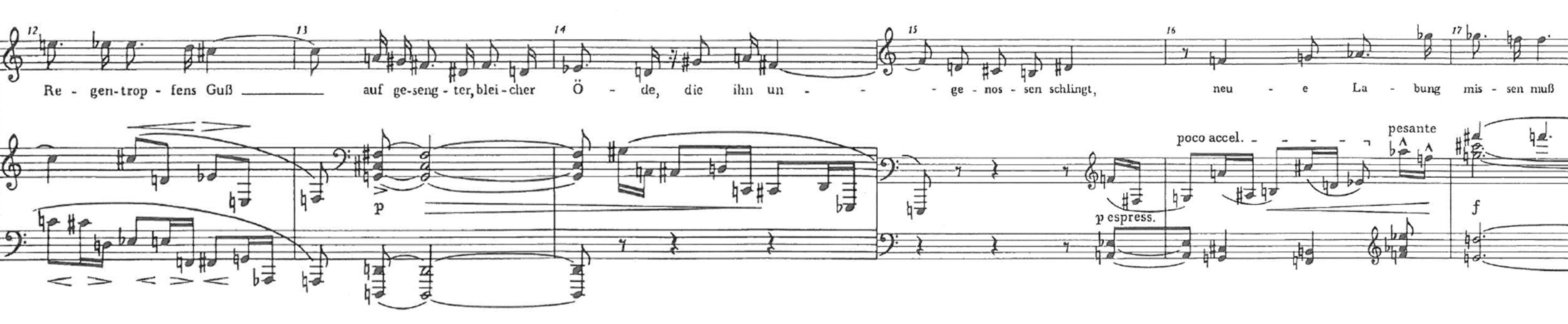

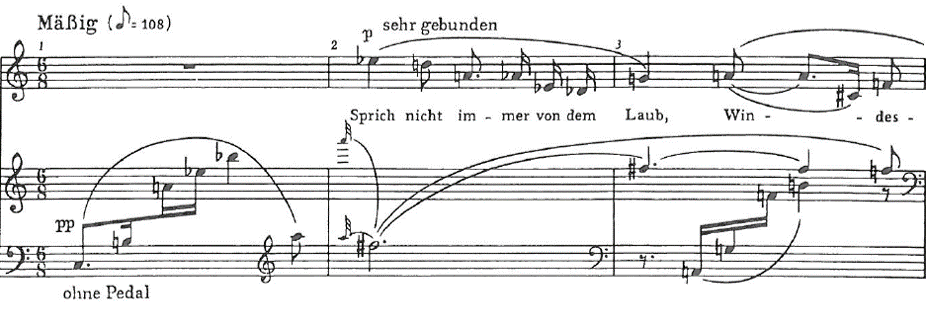

Figure 13: Arnold Schönberg: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15, No. III, bars 1-2

The anaphora “Kein staunen […]/Kein wunsch” in the second and third verse lends emphasis to the word “kein” and underlines the novelty and intensity of the speaker's feelings. The combination of alliteration and pararhyme in “meinen mienen” adds to the intensity of the poetry and requires a nuance of time for the singer to taste the words without losing the underlying energy. The third verse shares the verb with the second verse. Thus, the sentence gets shorter and more emphatic. The phrase “eh ich dich blickte” (before I saw you) is inserted before “rege” instead of added at the end. The important event of seeing the beloved for the first time is thus emphasised. Despite the many voices in the piano and the expressive hairpin dynamics, it is crucial not to get too loud too early, so the tension increases gradually towards that important moment.

While the first three verses speak of the past, the second part of the poem contains the speaker’s plea to the beloved to choose him as a servant at the present moment. In the fourth verse, the image of the folded young hands, a symbol of pleading or prayer, underlines his humility. The interlude prepares the plea. To me, it seems to illustrate how he throws himself on his knees and folds his hands in an urgent gesture. The young and inexperienced speaker asks the beloved to look upon his plea with “Huld”, an old term for benevolence or grace that places her in a socially higher position. The most striking place in the entire poem regarding language is the phrase “denen, die dir dienen”. The alliteration, the pararhyme “denen […] dienen” and the repetition of the bright vowel /i:/ underline the intensity of the speaker’s plea. His highest goal is to serve the beloved. I can use the ritardandi to convey the intensity of the pleading, while I think of the speaker’s youthful eagerness at the places that are in tempo or more flowing. I find it important to always start in piano again before building up the crescendi to illustrate the speaker’s agitation. It feels like he is getting hot and cold in turn. The text’s emotional qualities help against the temptation to get too loud immediately. This way, I can also avoid balance problems when the singer sings in the middle register.

In the sixth verse, the adjective “erbarmender” (merciful) stands out as the rhythm of the poem is softened by the only quadrisyllabic word that conveys the compassion the speaker attributes to the beloved. The plea reaches its climax at the transition from the sixth to the seventh verse. I try to play as intensely as possible, putting weight onto every note. As the singer has trouble hearing the piano when she sings this high and intensely, it is important not to get too broad but rather to feel the connection in the words in this melismatic setting.

In the last verse, the speaker describes himself as someone stumbling on a foreign “Stege”, which is an old word for small path. He seems to picture himself as a wanderer or pilgrim. The irregular metre of the verse illustrates his stumbling. Schönberg’s postlude appears to indicate that he recovers his balance and continues in his eager striving to please the beloved. I think of a gentle insecurity when I shape the final phrase of the song, which I try to keep open, being careful not to lengthen the last chord.

| Original poem67 | English translation68 | Norwegian translation | |

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

Da meine lippen reglos sind und brennen69 Beacht ich erst70 wohin mein fuss geriet: In andrer herren prächtiges gebiet. Noch war vielleicht mir möglich71 mich zu trennen, Da schien es72 dass durch hohe gitterstäbe Der blick73 vor dem ich ohne lass gekniet74 Mich fragend suchte oder zeichen gäbe. |

As my lips are motionless and burn I first notice where my foot got into: Other lords' splendid realm. It was perhaps still possible for me to part, Then it seemed that through high bars The gaze I had knelt before unceasingly Was seeking me questioningly or beckoning me. |

Da mine lepper er urørlige og brenner Merker jeg først hvor min fot har havnet: I andre herrers prektige rike. Ennå var det kanskje mulig for meg å skilles, Da var det som gjennom høye gitterstaver Blikket jeg hadde knelt foran uten opphør Søkte meg spørrende eller ga tegn. |

| Pronunciation | Rhyme scheme | Metre | |

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

daː ˈmaɪ̯nə ˈlɪpən ˈreːkˌloːs zɪnt ʊnt ˈbrɛnən ˌbəˈ|aχt ɪç eːɐ̯st voˈhɪn maɪ̯n fuːs ɡəˈriːt ɪn ˈandrɐ ˈhɛrən ˈprɛçtɪɡəs ɡəˈbiːt nɔχ vaːɐ̯ fiˈlaɪ̯çt miːɐ̯ ˈmøːklɪç mɪç tsuː ˈtrɛnən daː ʃiːn ɛs das dʊrç ˈhoːə ˈɡɪtɐˌʃtɛːbə deːɐ̯ blɪk foːɐ̯ deːm ɪç ˈoːnə las ɡəˈkniːt mɪç ˈfraːgənt ˈzuːχtə ˈoːdɐ ˈtsaɪ̯çən ˈɡɛːbə |

a b b a c b c |

˘–˘–˘–˘–˘–˘ ˘–˘–˘–˘–˘– ˘–˘–˘–˘–˘– ˘–˘–˘–˘–˘–˘ ˘–˘–˘–˘–˘–˘ ˘–˘–˘–˘–˘– ˘–˘–˘–˘–˘–˘

|

In the fourth poem, the speaker realises that he has entered another man’s territory. It might still be possible for him to leave, but then he seems to receive a sign from the beloved’s gaze that makes it impossible for him not to stay. Unlike in the previous poem, the speaker does not address the beloved directly but describes his inner strife.