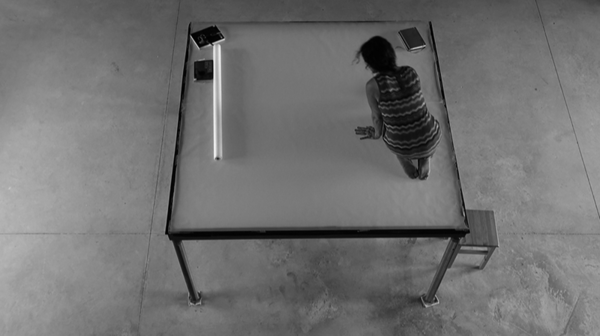

Translucent surface/Quiet body, redistributed investigates drawing as a choreographic activity and the material, visual and haptic organisations of moving-drawing in relation to gravitational force and surface dimension. The exposition presents the process and outcomes of recording a moving-drawing body from beneath a receiving surface.

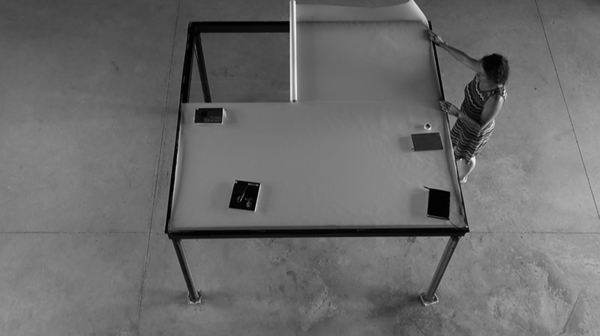

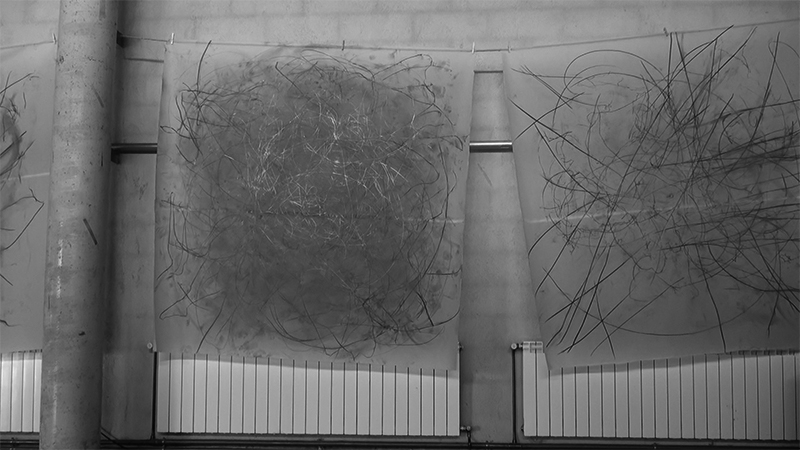

At the dance research centre L'Animal a L'Esquena, Celrá in Catalonia, I worked for two weeks in 2014 with a large metal table-like construction that was originally built for the DVD project Materials for the Spine, a study of choreographer Steve Paxton's pioneering dance teaching. On this platform, I was able to move and draw while being recorded from below, through the thick glass tabletop. I covered the glass tabletop with tracing paper in order to create partial visibility between above and below, as a translucent screen, the glass tabletop brought attention to the material and conceptual details of a moving-drawing practice in relation to horizontality, orientation and surface contact. A supine spectator or a documenting camera pointing upwards from the floor witnessed a different visual perspective of both the drawing action and of the material encounter between moving body and static paper-glass than would ordinarily be seen when performer and spectator are at the same level. In this latter instance, a performer working on the floor would fall below the spectator's eyeline.

I am interested in how this inverted view of surface contact complicates relations between seeing and touching, high and low, material and visual as more surfaces start to operate; skin, paper, glass, lens, screen. This view offers insight into how bodies (performing/spectating) orientate to the surface and how the horizontal plane is activated through moving-drawing. A re-consideration of art historian and critic Leo Steinberg’s notion of a ‘flatbed picture plane’ (1972) offers a reflexive concept through which to view the material, visual, and haptic aspects of a performer working on the floor. This is useful in proposing the emergent drawing residues as distributions of data, distinct from discussing drawing in terms of expression, embodiment, or performance-drawing.

Steinberg's flatbed functions like a ‘disordered desk’ that may equally include all types of material, formats, and scales. The flatbed gives an opportunity to shift away from subject matter and to animate an open mobility in which things are not fixed in hierarchical structure. This is partly due to the horizontal pull that holds everything low and on the surface.

Investigating distributions of data on receptor surfaces as evidence opens a theme of horizontality

in terms of gravity, surface contact, orientation, and touch. This has led me to connect notions of ‘flatness’ and ‘flat surface’ across art historical contexts and a physically-informed drawing practice operating in a choreographic field.

E v i d e n c e

o r i e n t a t i n g t o u c h i n g s e e i n g

Translucent surface/Quiet body opened up and provoked questions about what kind of data or 'evidence' was being gathered on the horizontal receiving plane versus the vertical recording plane. The term evidence, operating in the horizontal plane, opens a connection between seeing and touching and even the possibility of considering seeing as a kind of touching. The documenting camera in Translucent surface/Quiet body recorded a kind of evidence of surface touch to reveal a distinct orientation between body and surface. As the moving body rolled over the paper-glass, the documenting camera received the visual data of surface contact and in another moment and space this data was displayed on a vertical screen or projected onto another surface. The orientation of the body to vertical axis and horizontal plane and the direct connection between material encounter and viewing of reciprocal touch was interrupted:

Rather than presenting or alluding to three-dimensional space, the recordings considered as visual data presents a horizontal bed of information; they materially and visually present as a kind of map, aerial view, or collapsed surface space. There is a descriptive organisation of information on the surface rather than the perspectival view of the world through a window or frame, as found in the Italian Renaissance model and Albertian picture plane. As art historian Svetlana Alpers describes, Alberti’s notion of a picture was that ‘it was not a surface like a map but a plane serving as a window that assumed a human observer, whose eye level and distance from the plane were essential.’ (Alpers, 1983: 138) In her opinion, a ‘bird’s eye’ view of the world ‘describes not a real viewer’s or artist’s position but rather the manner in which the surface of the earth has been transformed onto a flat, two-dimensional surface. It does not suppose a located viewer.’ (Alpers, 1983: 141)

This map-like view also exists in Leo Steinberg’s notion of the ‘flatbed picture plane’ (1972) as '[a]ny flat documentary surface that tabulates information’ and as ‘radically different from the transparent projection plane with its optical correspondence to man’s visual field.’ (Steinberg, 1972: 88) The flatbed offers a way of considering drawing residues (material or digitally recorded) in terms of distributed or organised information rather than in terms of image production; information gathers and settles on surfaces and the receiving plane of the flatbed operates as a site of evidence.

There is a descriptive mode of painting in Dutch seventeenth century painting that art historian Svetlana Alpers distinguishes from the Italian Albertian perspectival mode that has dominated the development of art history. (Alpers, 1983: xx) She identifies, in cartography of the time, a shared interest in the mode of ‘picturing’, which inscribed ‘the world on a surface’ much like how Northern Renaissance painting presented pictorial information on a working surface. ‘[T]he graphic use of the term descriptio’ and other words used in map making suggest that the ‘pictures in the north were related to graphic description rather than to rhetorical persuasion, as was the case with pictures in Italy.’ (Alpers, 1983: 136). Alpers’ proposition suggests that ‘mapped images have a potential flexibility in assembling different kinds of information about or knowledge of the world which are not offered by the Albertian picture’ (Alpers, 1983: 139). This proposition informs the notion of the flatbed as graphic information rather than pictorial representation. Alpers also points to the Dutch painters’ interest in processes of printing and inscription, which overlaps with Steinberg’s image of the flatbed inspired by the horizontal flatbed of the printing press.

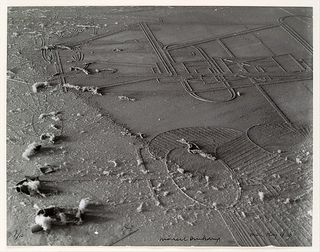

Man Ray’s rayographs were also concerned with the flat plane and a horizontal orientation to a light source. Objects placed on photographic paper underneath a lamp interrupted the light getting to the surface, leaving behind a negative image where the objects touched the surface. ‘The resulting spatial, tonal, and gestural qualities of these compositions challenged traditional modes of visual apprehension and representation.’ (MET MUSEUM, 2017) The camera-less procedure was a material process dependent on light not being able to touch the surface and producing an inverse evidence of touch and

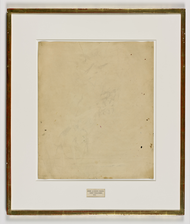

The transference of the earth’s spherical surface into a flat surface in map-making has a parallel in the transference of time-based dance movement into a horizontal receiving surface: the rolling body transfers an impression of its curved surfaces onto the flat support surface. This was digitally recorded in Translucent surface/Quiet body. The horizontal orientation of the documenting camera to the translucent surface is, however, preserved in the viewing on a vertical screen, similar to Man Ray’s rayographs or the cyanotype Female Figure (ca.1950) by Robert Rauschenberg and Susan Weil, which is similar to the rayograph but uses a different chemical process and direct sunlight rather than the a lamp in a darkroom.

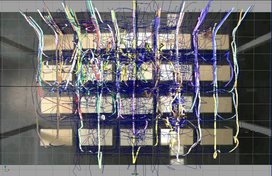

The interactive online site Synchronous Objects (2009) offers a platform for a wider audience to explore the underlying structures and systems of William Forsythe’s choreographic organisation in bodies and space in his work One Flat Thing, reproduced, ‘by translating and transforming them into new objects — ways of visualizing dance that draw on techniques from a variety of disciplines.’ (Synchronous Objects, 2009) The site opens up with the question of ‘what else might physical thinking look like?’ The objects in One Flat Thing, reproduced are animated, not static. Some are aerial views of the space, of the rows and columns of tables, and the choreography of dancing bodies that moves between, over, and beneath the tables. These aerial views present a collapsed graphic view of the space and the tables form a grid of tabletops over and through which a digital annotation is laid. By isolating one feature and presenting it as a flat organisation of data, one feature of the work is revealed that otherwise might not be perceived in the live event or documentation in vertical recording plane. Forsythe writes that such forms of mediating and disseminating choreographic thinking are not ‘a substitute for the body, but rather an alternative site for the understanding of potential instigation and organization of action to reside.’ (Forsythe, 2008)

In his essay Choreographic Objects (2008), Forsythe writes that ‘[o]ne could easily assume that the substance of choreographic thought resided exclusively in the body. But is it possible for choreography to generate autonomous expressions of its principles, a choreographic object, without the body?’ (Forsythe, 2008) In her article Affective Traces in Virtual Spaces: Annotation and emerging dance scores, dance researcher Hetty Blades (2015) distinguishes between notation, annotation, and recordings as modes of documenting live events and explores the use of digital annotation as a way to ‘draw the viewer’s attention to certain features of the [choreographic] work.’ (Blades, 2015: 27) Blades also uses the term ‘choreographic object’ to include new forms of ‘“score”, “archive” and “installation”’ that are ‘created with the intention to articulate and disseminate choreographic thought.’ (Blades, 2015: 26) She argues that these ‘choreographic objects’ consider the ‘work’s potential to exceed its form and generate a felt sensation that exceeds its structure.’ (Blades, 2015: 32) That a live event might exceed its form, either through other objects or systems of information generated from them, allows choreography to be extricated from the dancing body and

T r a n s l u c e n t s u r f a c e / Q u i e t b o d y, r e d i s t r i b u t e d

K a t r i n a B r o w n

C h o r e o g r a p h i c v i e w

Translucent surface/Quiet body as a choreographic documentation process allowed me to consider notions of ‘flatness’ in my moving-drawing practice and the emergent outcomes as flatbed distributions of material and digital data.

Drawing could be viewed as material-visual-haptic.

Working with the table-like construction and translucent screen enabled me to incorporate, articulate and highlight the various and often coinciding capacities of surface to support, receive, record, touch, screen, and display data, towards developing a choreographic view of drawing.

This exposition, extending out from a left over a two-dimensional online page presents another surface on which to re-distribute observations, materials, and concepts as extended making-thinking, as documentary work-surface, and as flatbed.

Inviting viewer/reader to scroll up, down, right, left, to zoom in, out, to click or make a leap through the navigation map, to brush past or linger for a while.

D o r s a l

t r a n s f e r r i n g a s e n s a t i o n o f w e i g h t

The digitally recorded impressions in Translucent surface/Quiet body allow some aspects of the dark, other, dorsal, inside of the body to become visible on the surface as evidence of a ‘sensation of weight’: a relationship between weight, skin, and movement appearing in the horizontal plane of the receiving surface. In the DVD, Material for the Spine: a movement study (2008), choreographer, dancer, and teacher Steve Paxton describes bodily orientation through an understanding of gravity as a force in relation to surface. Paxton was a pioneer in the development of the dance form Contact Improvisation in the 1970s; this was an ‘improvised dance form based on the communication between two moving bodies that are in physical contact and their combined relationship to the physical laws that govern their motion — gravity, momentum, inertia.’ (CONTACT QUARTERLY, ca.1979). Thirty years later, Paxton collaborated with Contredanse, a centre for dance research based in Brussels, to produce Material for the Spine, a technical articulation of relations between the spine, weight, and sensation as developed in his movement practice. The table-like construction I worked on to develop Translucent surface/Quiet body at L'Animal was originally built for Steve Paxton to move-talk on. On the DVD, Paxton says:

It is a system for exploring the interior and exterior muscles of the back. It aims to bring consciousness to the dark side of the body, that is the ‘other’ side, or the inside, those sides not much self-seen, and to submit sensations from them to the mind for consideration. (Paxton, 2008)

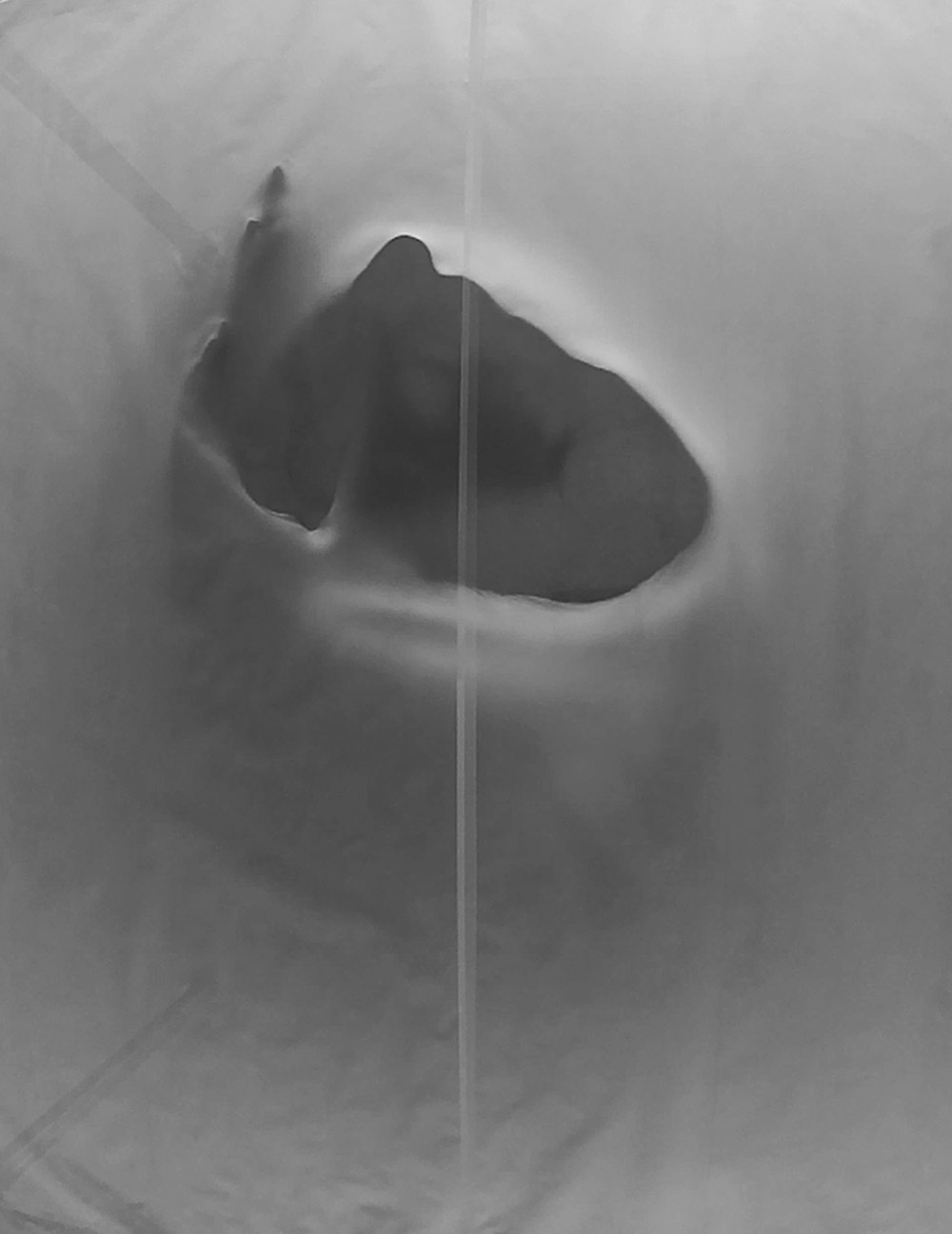

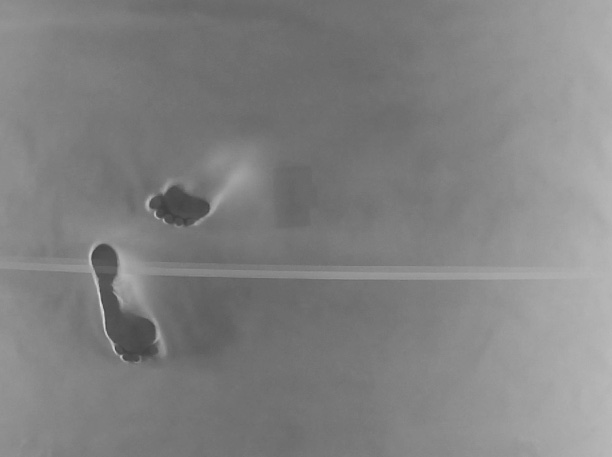

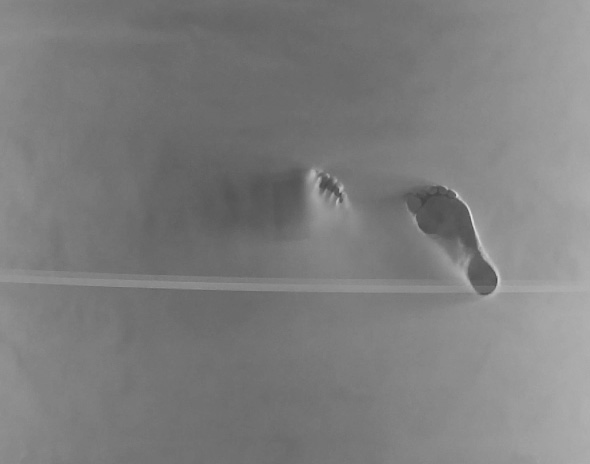

Paxton gives insight into a body’s movement of mass through the technology of the body’s spine moving with gravity. The body works with gravity, weight, and floor-surface in order to twist, roll, and ‘undulate’ in different ways through the spine, for a body understands its relation to the surface ‘through sensations of weight’, through the joints, and through the skin. (Paxton, 2008) In one section of his DVD, Paxton stands on a transparent glass ‘floor’, meaning the viewer is presented with the soles of his feet filmed from below, as they press against the transparent glass. As he stands, Paxton is slightly moving and talking about how he can feel a smooth surface, saying, ‘these flat places reflect the foot’s ability to adapt to the surface’ as an ‘accumulation of [his] whole body’s weight' held onto the surface through that small area of contact as 'weight accumulates down the body’. (Paxton, 2008)

We’re talking about a spherical space in the planet and being called to that surface in all directions by gravity – and we’re talking about different relationships to a surface, all of which we understand through the sensation of our weight through different joints, different aspects of the surface, especially the skin and the deformation of the skin the deformation visible here. The skin can tell the brain what’s happening relative to the surface. The brain has no sensations. The brain has information. The body has the sensations. (Paxton, 2008)

Paxton is proposing that the (dancing) body needs to shape itself from within by maintaining sensorial focus or ‘physical thinking’ with the sensations of weight and by managing its constantly changing relation with the floor as supporting surface. This creates an articulation of (dance) movement from ‘normal to formal’. The ‘formal’ is a refined and embodied implementation of the ways in which we ‘normally’ walk, sit, lie, and generally orientate in relation to floors, walls, other things, and bodies; it is a practice of drawing attention to the spine as an invisible but sensible place inside the body; a proposition that the dancing body must work and think and understand its own dimensionality with what it cannot see.

Paxton offers an understanding of movement in three-dimensional space informed by surface contact and sensation of pressure between a moving body and static surface with the ‘limitations of vision in not being able to see the head, back and other sides of the body while moving.’ (Paxton, 2008) Dramaturge Jeroen Peeters describes a process of ‘seeing through the back’ to investigate visuality in performance and proposes that ‘notions of the spinal support of man’s upright stance and the blind space behind our backs’ can ‘provide an anthropological ground for the invitation to move, perceive, imagine and think through the back.’ (Peeters, 2014: 291)

Working with a table-like construction, a moving-drawing body is documented from above and below

a translucent surface.

A 2m x 2m elevated platform functions as both a hard smooth ground for the performing body and a viewing screen for the documenting camera below.

Tracing paper with a weight of 90gms operates as a translucent screen between glass and skin as translucent screen. Natural daylight enters the studio from two sides creating a light box effect and accentuating the stark greyness of the installation.

The two viewing perspectives (above and below) offer distinct information about gravitational forces and surface touch between paper-glass and body-skin, as what is visible on one side of the screen may be obscured from view on the other.

She becomes adept at moving within the edges of the 2m x 2m surface area of the elevated platform. She leans her weight on parts of the body (lower arm, foot, hip, shin, shoulder blade) so that other parts of the body can lift away from the paper-glass surface. She twists, extends, curls and reconfigures her body around areas of surface contact between body-skin and paper-glass. She works on softening her body and opening her skin to meet the hard, smooth surface.

the dorsal as a surface force that can open other dimensions

in the body's moving thinking connecting

in the world

Translucent surface/Quiet body has evolved out of a 15-year-long relationship with moving and drawing, during which I have been working with charcoal, graphite, and chalk as precarious materials on floors, walls, and paper in different choreographic configurations and collaborations. Remaining curious about drawing in relation to philosophical ideas around trace, future-past and absent body, my current research as choreographer has increasingly encompassed ideas of material agency and the political implications of a performer working on the floor. I have been using the notion of intersect as a conceptual tool for observing and articulating the encounter and orientation between body and surface: the intersect creates a kind of suspension, a gap in which to observe the material-visual-haptic details of what is happening, appearing and remaining on the surface.

F l a t b e d

v i e w i n g p e r s p e c t i v e s

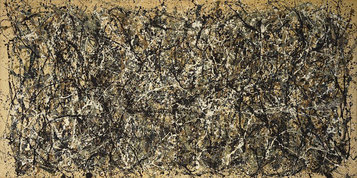

In 1972 art historian Leo Steinberg proposed the ‘flatbed picture plane’ as a critical model for considering artworks emerging in the late 1950s and 1960s. In his view, certain paintings were breaking with the Renaissance picture plane in ways that other avant-garde art movements in Europe and America — including Cubism, Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, and Colour Field Painting — were not. (Steinberg, 1972: 90) Steinberg suggested that works by some artists including Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, and Jean Dubuffet were proposing a ‘radically new orientation’ in their pictures: an orientation that was not founded on any ‘prior act of vision’ or ‘head-to-toe correspondence with human posture.’ (Steinberg, 1972: 84)

What I have in mind is the psychic address of the image, its special mode of imaginative confrontation, and I tend to regard the tilt of the picture plane from vertical to horizontal as expressive of the most radical shift in the subject matter of art, the shift from nature to culture. (Steinberg, 1972: 61)

Steinberg identified Rauschenberg as one artist whose artworks no longer ‘simulate[d] vertical fields, but opaque flatbed horizontals.’ (Steinberg, 1972: 89) Rauschenberg approached his mixed media collages or ‘combines’ such as Bed (1955) as work-surfaces; using diverse materials, textures and objects and at the same time he worked against any ‘topical illusion of depth[:] the surface was casually stained or smeared with paint to recall its irreducible flatness. (…) The picture’s “flatness” was to be no more of a problem than the flatness of a disordered desk or an unswept floor’ (Steinberg, 1972: 89). Steinberg wrote:

Any flat documentary surface that tabulates information is a relevant analogue of his [Rauschenberg’s] picture plane — radically different from the transparent projection plane with its optical correspondence to man’s visual field. (Steinberg, 1972: 88)

The flatbed, like a ‘disordered desk’, offers the potential for everything to be be included; that all types of material, formats, and scales can be equally present and presented. It gives an opportunity to shift away from subject matter, to animate an open mobility in which things are not fixed in hierarchical structure, and this is partly due to the horizontal pull that holds everything on the surface.

In Bed (1955), Rauschenberg uses an old quilt rather than canvas to paint upon. The quilt is already a kind of tabulated flatbed, with its rectangles spreading in all directions along two dimensions, yet it becomes literally a flat bed when the pillow is added. This is still true when suspended vertically on the wall. (Steinberg, 1972: 88) Steinberg proposed a distinction between the pictorial picture plane of a painter’s canvas that is seeking in some way to represent or evoke the ‘world’ or ‘nature’ and the ‘flatbed picture plane’ that ‘work[s] in the imagination as the eternal companion of our other resource, our horizontality, the flat bedding in which we do our begetting, conceiving, and dreaming.’ (Steinberg, 1972: 88)

It might be argued that Rauschenberg’s Bed does have ‘a right way up’ when exhibited on the wall with the pillow at the ‘top’. A map, likewise, has a specific orientation, with north at the top. Steinberg’s flatbed does pose an interesting problematic in relation to some particular examples such as these. Similarly, there would be a question too of why Steinberg clearly does not regard the paintings of Jackson Pollock or Helen Frankenthaler as exemplifying his ‘flatbed picture plane’. In particular Pollock’s paintings such as Full Fathom Five (1947) and One: Number 31, 1950 (1950) can be seen as a distribution of material operating with gravity and a non-hierarchical organisation of visual information. Is it the rhythmic patterns of Pollock's drip-painting actions? For Steinberg, such a technique is still concerned with representing or somehow evoking ‘nature’ or the ‘unconscious’. That Pollock's canvases were on the ground was only a means to an end; their paintings continued to be made to operate in the vertical plane of vision. (Steinberg, 1972: 84) Perhaps it is in how Rauschenberg’s Bed and the recorded impressions of Translucent surface/Quiet Body, orientate the viewer in relation to their own horizontality that is relevant.

In Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953) Robert Rauschenberg applied ‘erasing’ as a as a kind of drawing action, methodically erasing the diverse paint, oil, and crayon previously applied to the artwork by the abstract expressionist painter Willem De Kooning. Rauschenberg’s ‘drawing’ is evidence of the procedural action undertaken to remove any evidence of de Kooning’s painting. Steinberg writes that in this work, Rauschenberg ‘was changing — for the viewer no less than for himself — the angle of imaginative confrontation: tilting de Kooning’s evocation of a worldspace into a thing produced by pressing down on a desk’ (Steinberg, 1972: 86-87). In Dust Breeding (1920), Man Ray photographed the accumulating dust on a section of Marcel Duchamp’s artwork, The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) (1915–23). The transparent glass panel was stored in a flat position, so the photograph reads as an aerial view of a kind of landscape, diagram, or textural terrain: a surface of dust distribution. Interestingly, these two works both respond to an existing artwork and, through different surface mediations, present a new work as a site of evidence.

Steinberg’s flatbed offers a descriptive organisational view of the world based on a non-hierarchical distribution of information. It is this aspect in particular that is relevant to this project’s themes of horizontality and orientation, informing a choreographic view of drawing in terms of surface contact, distinct from drawing in terms of mark-making or action painting. Steinberg was writing at a time before digital media in the arts and does not overtly consider any parallel developments in performance, dance, or choreography in this period of the 1950s. There is now a prevalence of satellite and aerial photography, in which the world can be seen from above and at an increasingly great distance. Reconsidering the flatbed in relation to the choreographic generates nuance that can expand the term to organisations and mediations of movement and to choreographic objects.

In 2001, choreographer La Ribot presented Despliegue, a video-installation consisting of two videos, one on a TV monitor and the other as a floor projection. The videos were in real-time and were recordings of the same event but each presenting a different viewing perspective. The videos showed La Ribot installing all the props, costumes and objects that she had used in her solo series Distinguished Pieces onto a large grey canvas, props that were later gathered in the performance Panoramix (2003). The items were arranged much like a map or landscape. In the videos, she also placed her body among the objects, almost disappearing between them in the overhead view.

The grey canvas that La Ribot pulls into the frame of the overhead camera stretched over the floor, with some floor still visible around the edges of the frame. The aerial view works as an ‘opaque flatbed horizontal’, as all objects collapse and then spread into two dimensions. This is visually reminiscent of one of Rauschenberg’s mixed media collages, with a similar effect of working against any content-related illusion of depth. In Despliegue’s aerial overhead projection on to the floor, La Ribot does not allow the viewer to forget that they are looking at the floor.

The aerial view allows the spectator to hover and see the world described.

Translucent surface/Quiet body is one of three configurations of body, material, and surface that together formed my practice-based PhD research (2018), located in a field of choreography as expanded practice in contemporary art. The series of ongoing durational drawing scores She's only doing this investigated line through task-based constraints and repetition, developing the idea of score as action, performance event, and graphic residue. what remains and is to come (2011-2014), produced in collaboration with choreographer Rosanna Irvine, explored the material relations of and between charcoal, paper, body, and breath. Translucent surface/Quiet body, produced in different formats between 2014 and 2017, proposed another perspective, activating the horizontal plane.

I n v e r t e d v i e w

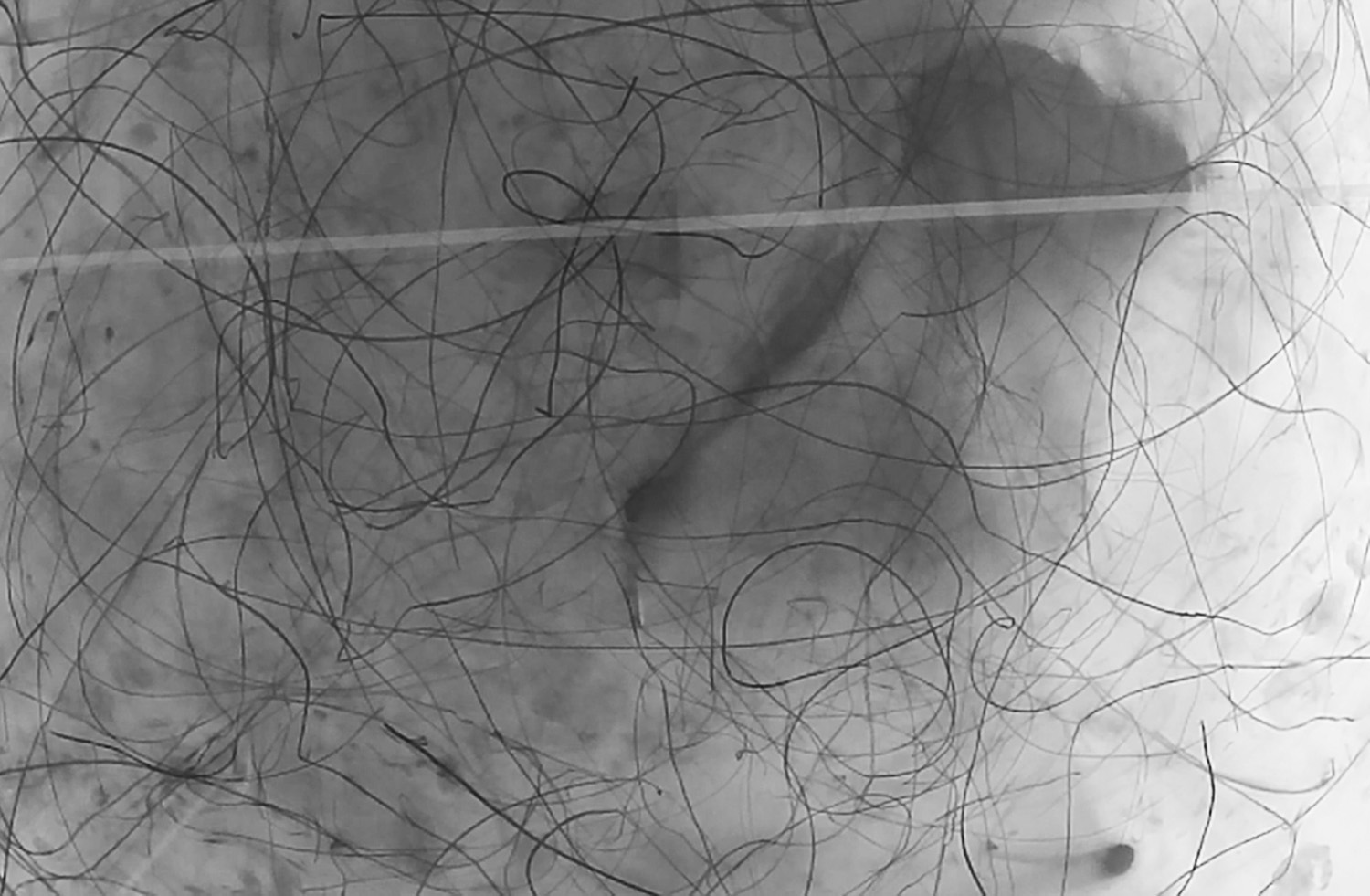

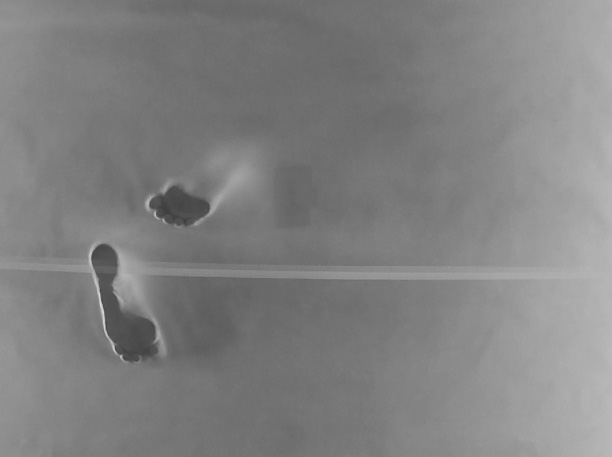

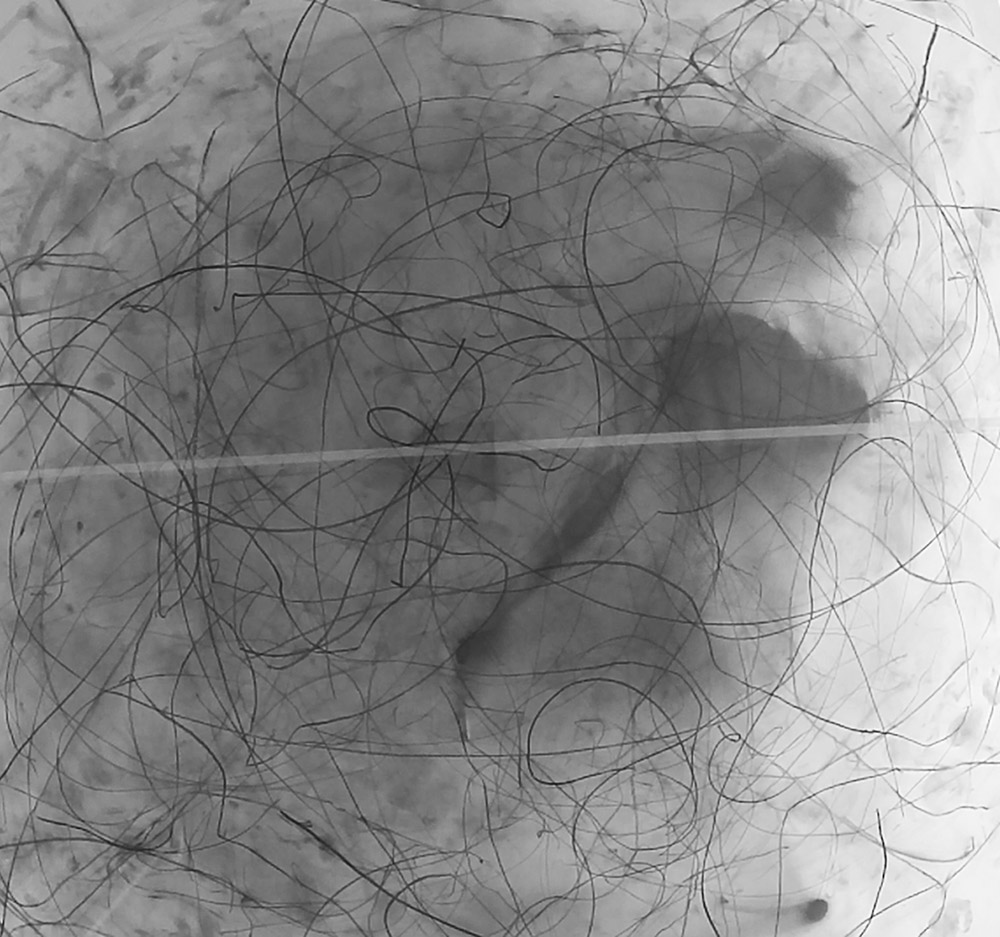

The surface contact between bare skin and paper-glass appears on the screen as dark flat shapes that continually transform and reshape as the body moves. It is the pressure of this hard surface on a soft body that becomes visible on the screen. The video recording shows directly the contact area shared by skin and paper-glass, which is usually felt but not seen under the body, and only becomes evident once the body has moved away from the surface, revealing a mark, imprint, or trace of where it previously lay.

The flattened shapes offer an underside view of moving mass. These bodily shapes, however, reveal little of the textural details of skin, and are a different kind of material information of the body. The inverted view through the translucent screen presents an immediate visual translation of pressure and surface contact, offering a perspective on the effect of gravity as the body's mass and movement is made visible.

Looking closer at these transforming shapes, the varying hues and levels of dark and light are relative to the degree of pressure between the body and its support surface. The more the body presses down, the darker and more distinct the shape that appears on the screen below. As the body lifts its weight from the surface, the shapes become lighter, more blurred until they disappear altogether. Due to the light-box effect, the body remains visible even when lifted slightly away from or brushing lightly against the paper-glass. This extends the visible areas of surface contact, giving shape to the movement into and away from direct contact and the different levels of pressure involved in the body’s movements. It reflects the transference of weight and rolling of the body over the flat surface.

I wonder in how far this increasing lightness/decreasing visibility creates a sense of depth in the recorded image: the voluminous body in three-dimensional space. Yet these lighter areas also remain in the surface plane as data; an effect accentuated by its grayscale, which flattens an image into one layer.

The choreography appearing on the screen is

a surface movement of light and dark tonal gradations

a translation of the body’s moving mass: a flatbed.

S c r e e n

The term ‘screen’ refers to two different objects: the translucent surface of the paper-glass in the studio installation and the computer display screen. The first operates in the horizontal plane, filtering light, screening the body, and allowing some visual information to be gathered by the documenting camera below. The second operates in the vertical plane, emitting light and presenting the mediated visual data. Another key distinction: the material translucent screen functions as a work surface while the digital viewing screen as a display surface.

The translucent surface simultaneously divided and connected the performer above and the documenting camera below as well as isolating some visual information. The material actuality of the hard, smooth paper-glass platform and the pressure between platform and performer became visible through the flattened areas that were appearing on the screen below.

The video footage, viewed on the display screen or projected onto another vertical surface, tilts the grounds horizontality to a vertical position - and yet it holds onto that same ground perspective. The two screens visually coincide and present a flat collapsed space, an inverted aerial view of surface contact between moving body and static receiving surface.

light filtering through a paper-glass translucent screen visual data settling like dust on the camera lens

In Translucent surface/Quiet body, the translucent screen realised another kind of touch over distance: its interrupted view of reciprocal touch from underneath the paper-glass. The view screened on a laptop display screen or projection surface is a mediated organisation of data and this visual data is organised over different surfaces through the documenting camera, paper, floor, wall, and, now, in this exposition.

Light might also be considered as a mode of touching, with the effects of light parallel to those of touch: light touches surfaces, illuminates surfaces. In Translucent surface/Quiet body, light touches the translucent paper, partially filters through the paper-glass screen to touch the eye of the documenting camera. When viewed on the screen, light touches the surfaces of the spectating eye. Architect and academic Juhani Pallasmaa writes, ‘(t)he eye is the organ of distance and separation, whereas touch is the sense of nearness, intimacy, and affection. The eye surveys, controls, and investigates whereas touch approaches and caresses.’ (Pallasmaa, 2005: 46) Perhaps the flatbed operates somewhere between touching and viewing, between close proximity to the skin and the distance of an aerial view.

The screen’s capacities to conceal, divide, filter, and connect — and also to present and display information — generates a complex set of surface operations in relation to touching, viewing, pressing, and appearing. The screen interrupts the immediacy of the material encounter and sensation of weight, disturbing the viewer’s orientation of body/surface and vertical/horizontal.

T o u c h

o r i e n t a t i n g s k i n s c r e e n

French writer and philosopher Jean Luc Nancy writes that the ‘body exists against the fabric of its clothing, the vapours of the air it breathes, the brightness of the lights or brushings of shadows’ (Nancy, 2008: 150-153). The body orientates itself in the world partly through what it touches and what touches it, whether that is clothing, air, light, ground, charcoal, or paper. It is particularly on the skin, where ideas around body and surface increasingly overlap and connect. Relative to touch, the skin can be considered in its material and direct encounters; the viewed, translucent screen of the tabletop provides another kind of skin that divides and joins the actual to the digitally-recorded.

Academic Steven Connor writes, ‘[as] I touch the world, they [objects] seem to rise to their own surfaces, to meet me in the shape that I present to them.’ (Connor, 2004: 35). A notion or image that bodies and objects rise to their surfaces in order to encounter one another complicates an understanding of skin, surface, and touch.

Choreographer and academic Erin Manning proposes that the ‘skin that touches and is touched is continually rebuilding itself from the outer to the innermost layers. To reach toward skin through touch is to reach toward that which is in a continued state of (dis)integration and (dis)appearance.’ (Manning, 2007: 85) Manning suggests that skin’s ability to renew itself forges a relationship between skin, touch, and memory; that ‘[i]f we locate the skin as the receptor that never quite remains itself, we can begin to appreciate the ways in which touch can never be more than a reaching-toward the untouchable.’ (Manning, 2007: 85) She writes that ‘[i]n addition to its regenerative qualities, there is also the issue of forgetting: if we want touch to last, we must touch again, lest the skin “forget” the touch we can feel but momentarily.’ (Manning, 2007: 85) The process of forgetting touch and the necessity to touch again and again in order to stay orientated in the world generates a sense of the body as unstable and as engaging in shifting material relations with other performing objects (and bodies). In performance, there is a continual process of recycling touch; touching, shedding, existing through touch, forgetting, re-touching in order to perform, to present, to be present and co-present: a repetition of surface experience.

In her programme notes from the performance Right at Presence (2009), Rita Roberto writes:

I don’t become the things I touch, I touch them. I take the air and give it back. I would not be anymore if the air hadn’t been inside me, but the air was not me at any moment. There is this constant cooperation of things in touch […] but to touch is also to be at the border that separates me from the things that I am not. It is in fact, this separation that makes touch possible. The touch becomes the border.

(Rita Roberto, cited in Allsopp, 2009: 253)

In proposing separation and cooperation as condition of touch in the context of performance, Roberto highlights touch ‘at the border’ between the animate and inanimate and a consideration of touch as dynamic.

B a r e

b a r i n g s u r f a c e s k i n

In the installation of Translucent surface/Quiet body, there was a practical and conceptual necessity for the performing body to become a naked, or bare body. Moving-drawing on the installation’s elevated platform disturbed any direct material encounter and any evidence of reciprocal surface touch between body-skin and paper-glass. This bare body opened up questions around nakedness and nudity, specifically the female nude in Western painting traditions and the use of nudity in performance art traditions. Yet there was also something distinct to this bare body: although willing to address an historical lineage, there was also a desire to look choreographically at a different operation of bareness. John Berger explained in the BBC series Ways of Seeing (1972):

To be naked is to be oneself.

To be nude is to be seen naked by others and yet not recognised for oneself.

A naked body has to be seen as an object in order to become a nude. […] Nakedness reveals itself. Nudity is placed on display. (Berger, 2008: 48)

In The Artist’s Body (2012), Amelia Jones and Tracey Warr address how developments in performance art in the latter half of the twentieth century revealed a shift in artists’ perceptions of the body, which was being used not simply as the ‘“content’’ of the work, but also as canvas, brush, frame, and platform.’ (Jones & Warr, 2012: 11) However what is it to be naked in a choreographic work and how is nudity or nakedness implemented as a choreographic strategy? Adrian Heathfield offers another option, using the term ‘bare’ to articulate his experience as spectator of the choreographer La Ribot performing in Panoramix (2003) and to explore her nudity as a choreographic strategy in relation to contemporary cultural and historical arts contexts:

Though she spends much of the performance without clothes or barely dressed, La Ribot is not nude. Nudity is a kind of wearing of the skin as a sign of revealed self, it is swathed in eroticism and projections of gender. Naked might seem like a better word to describe her condition, but even that seems too much of a proclamation: there is no definitive statement here in this stripping of the cloaks of culture.

More accurately, the state to which she constantly returns is that of bareness. […] The kind of blank bareness that is unresponsive to erotic projection, intimate, but impersonal, saying very little about itself, but allowing actions and objects to speak in relation to it. (Heathfield, 2004: 25)

Over two hours, La Ribot performs a series of short ‘piezas’, or pieces, one after the other in different places and orientations in the space. The spectators never quite know where she might go next or when. They must either follow her, watch from a distance, gather around her, or they are unexpectedly confronted by her proximity as she leans on or slides down the wall next to them. Each piece involves a different costume and/or prop and La Ribot’s nudity within each piece also operates differently. Sometimes it is sexual, at other times political, neutral, minimalist, simple, or complex. However, there is another operation of her nudity as bareness that is present throughout the whole performance, one that is distinct from the particular expression of her body in each piece. In the documentary film La Ribot Distinguida (2006) by Luc Peters, which follows the installation and performance of Panoramix at Tate Modern, La Ribot talks of the relation between audience proximity and nudity, explaining that her nudity is ‘just another thing’, another material that she can use in her process, much like she might use a piece of music, a chair, a dress, or any other object (Peters, 2006). In the film she says, ‘I think I can escape or that they [the audience] do not threaten me, because I am naked. It means that my being naked which is utterly violent to them makes me untouchable. How can I say? It saves my life.’ (La Ribot, cited in Peters, 2006)

La Ribot seems to imply that her bareness created a separation between her body and those of the spectators. In the spatial proximity of bodies, her bareness operates as a kind of screen. Bareness itself, then, operates as a choreographic layer in the performance as La Ribot’s body, neither nude nor naked, continually dressing and undressing. The body is exposed and re-configured as a moving object amongst other objects.

La Ribot’s bareness in Panoramix seems to represent nothing other than itself, performing alongside and with other materials and objects of the performance. It generates its own conditions or politics for the body as a performer, an agent, a human being, an art object, an appearance. La Ribot’s bareness operates again and again as a fresh blank page or interface through which to experience and navigate the whole event: Panoramix. Heathfield’s notion of bareness connects the bare female body in performance to the choreographic rather than to genres of live art and performance art, in which the body is often explored in relation to endurance, political resistance, or sex. This bare body might offer another category of artist body and object body to those presented in Amelia Jones and Tracey Warr’s The Artist’s Body (2012), in which the body in performance is explored in relation to abject, transgressive, absent or gestural themes. The choreographic bare body might be able to shed some of its historical layers and expose its objecthood in a way that it is ‘bareness’ itself, operating as a choreographic object.

‘Bare’ as conceptual term finds affinity with the body’s surface exposure and potential surface touch with other things, unlike concepts linked to the social body or the erect, well-built, standing body. Both bareness and skin-as-a-surface operate in movement rather than as a state. As artist and writer Katharina Zakravsky writes in her essay ‘Unbareable’:

To be bare is not a state, it is dynamic, a potentiality. Baring is a dangerous power, a pull and where ever [sic] there is desire it can never be bare enough. The integrity of the skin ends layers and layers outside of the body. To touch the bare skin would mean cutting it: if the body were not always already the touching of another touch (Zakravsky in Gareis & Kruschkova, 2009: 347)

Zakravsky complicates the ideas around skin, limit, layer, and touch and suggests that performance is itself a process of baring;

[I]t is not the search for a core, it is the very taking off of layers that draws us into the art of baring. Each layer is as precious and as contingent as the one underneath. If there is no discovery of a final core legitimizing the operation, any activity of baring has its ethical and political risks. (Zakravsky in Gareis & Kruschkova 2009: 347)

Performance, then, can be approached as a process of shedding, like the skin continually shedding its layers. Performance not as digging into the depths of matter but allowing the surface appearances, fleeting and temporary as they may be, to be illuminated, revealed, and dispersed, and the superficial layers to have an impact. As Erin Manning proposed in her book Politics of Touch (2007), the shedding of layers means we have to keep touching — lest we forget.

s

h

e

i

m

a

g

i

n

e

s

t

i

m

e

i

s

w

o

r

k

i

n

g

d

i

f

f

e

r

e

n

t

l

y

f

o

r

a

v

i

e

w

e

r

o

n

t

h

e

o

t

h

e

r

s

i

d

e

s

h

e

f

e

e

l

s

h

e

r

h

a

i

r

s

b

r

u

s

h

i

n

g

s

u

r

f

a

c

e

,

a

s

l

i

g

h

t

s

t

a

t

i

c

b

e

t

w

e

e

n

h

e

r

s

k

i

n

a

n

d

p

a

p

e

r

lines appearing, spreading in all directions over smooth paper, accumulating, surfacing as another screen

D r a w i n g

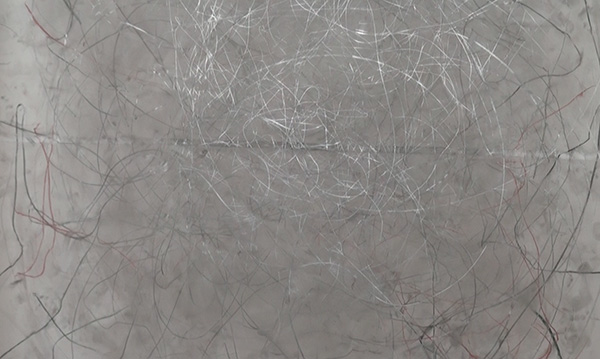

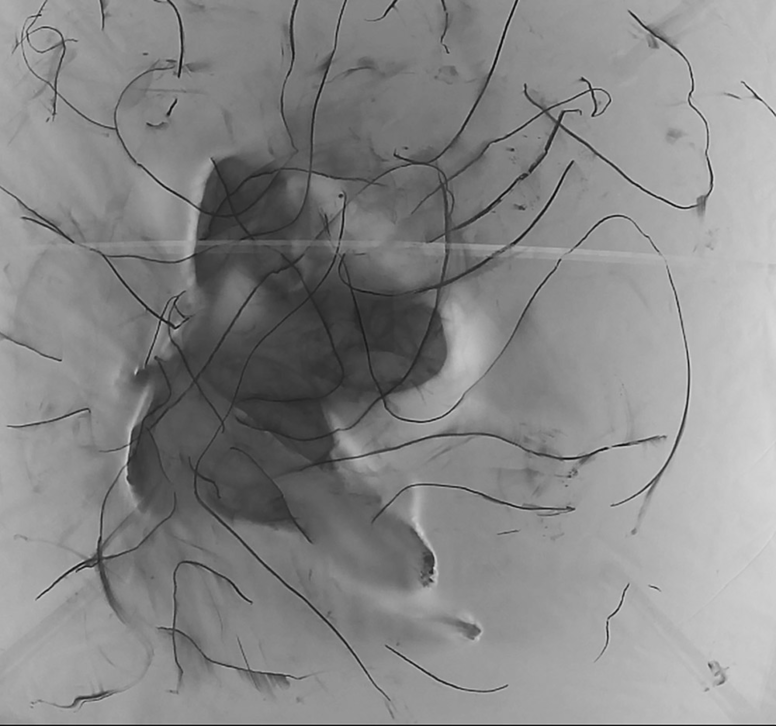

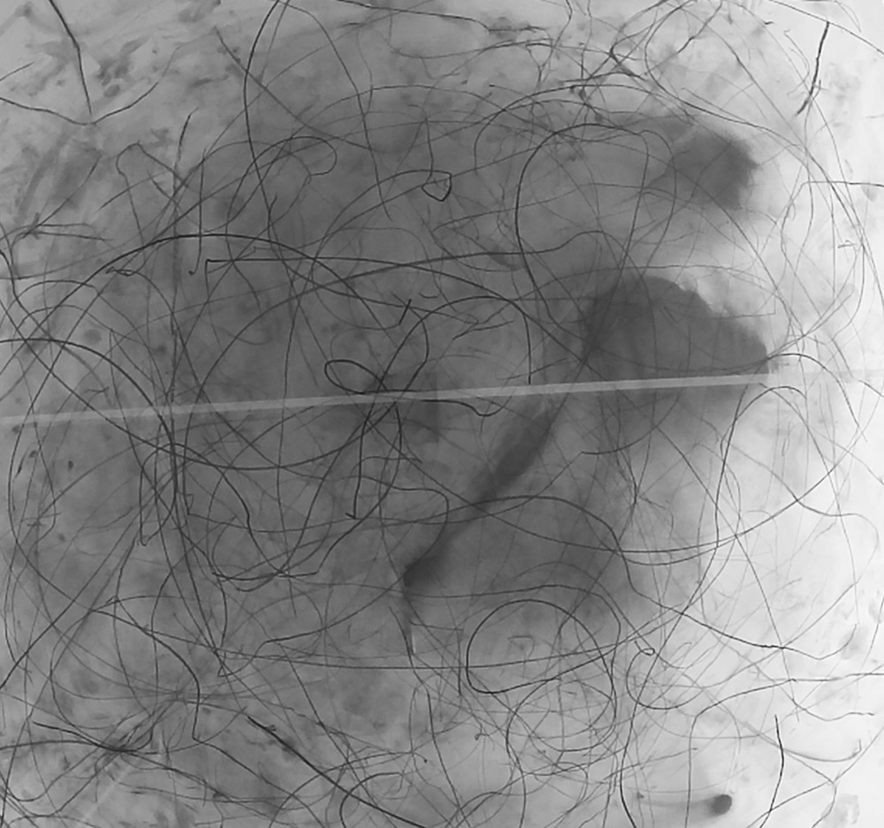

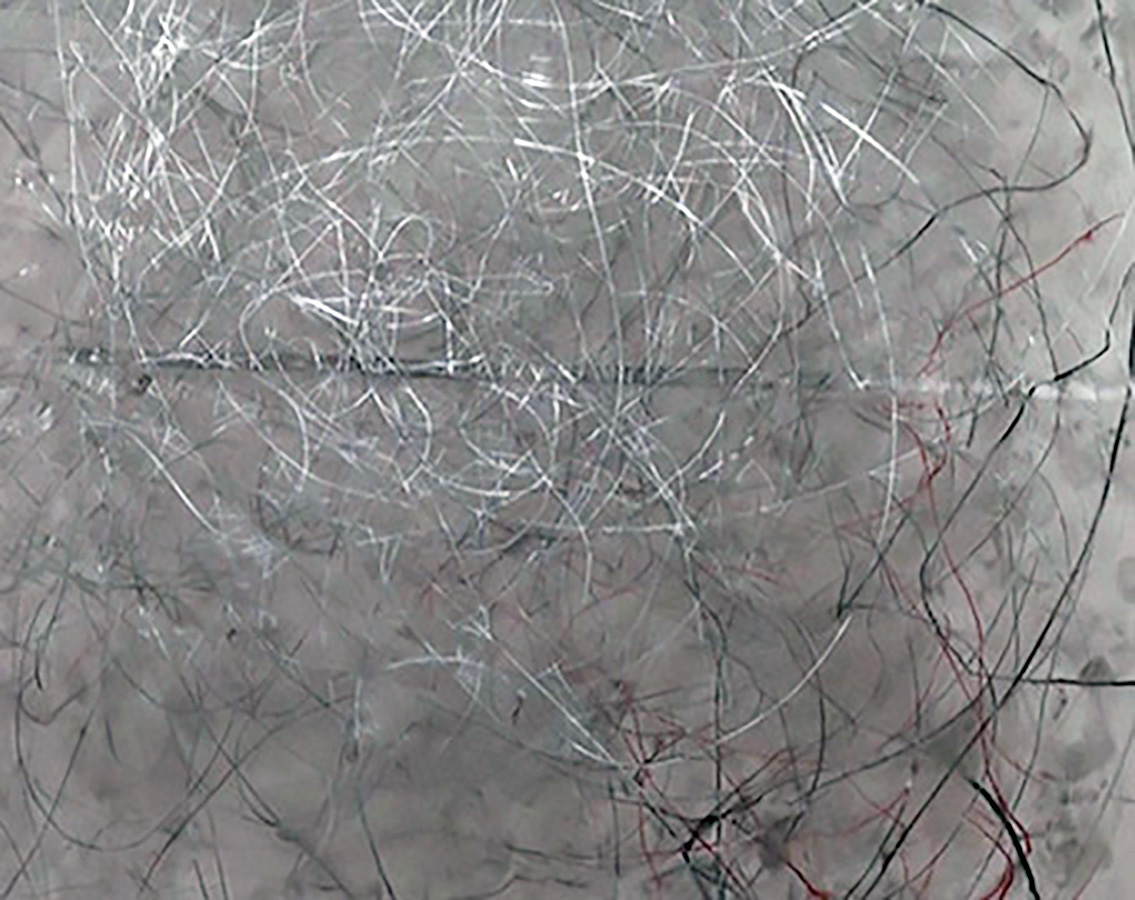

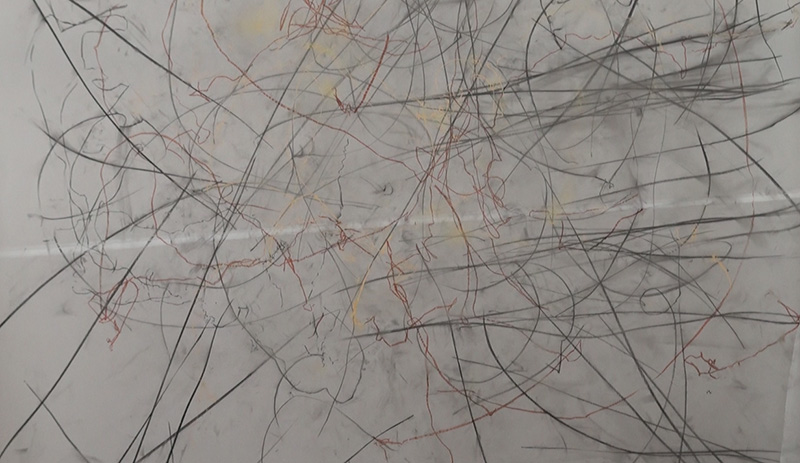

In the video recording from below, there seemed to be two kinds of drawing appearing, as the performer drew with charcoal while rolling and twisting on the paper-glass, each with a different relationship to the surface and to the body;

1.The movement of mass visible as transforming flattened forms of surface contact.

2.The charcoal lines that appeared on the screen and stayed and accumulated depending on the task or score.

The contact point between charcoal stick and paper is visually perceptible as lines appear, move and cease, but the body's movement towards or away from the surface transitions between movement and emergent trace are less directly visible, for instance, when the body is approaching but not yet touching the surface. The paper-glass as translucent screen visually disconnects the movement and the charcoal trace of that movement.

In this way the video recording from below presents a different organisation or proposition of drawing as choreographic activity: the charcoal lines as material traces independently and increasingly appear, cover, and remain on the surface while the dark flattened impressions of contact between still and moving surfaces constantly transform as an animation of moving mass and disappear, leaving no permanent material mark.

The organisation of drawing in the video recording from below creates an interruption between what the performing body is doing on the surface of the paper-glass and what the viewer sees appearing on the surface of the screen. Lines appear and disappear as though digitally triggered by an annotation tool rather than by a human agent. The charcoal lines appear to move autonomously and in covering the paper, they create another screen that increasingly conceals the performing body. Yet, for the viewer there is no behind or in front - everything is surface.

Working on the table was different from my other experiences of working with charcoal on paper. On these other occasions, performers and spectators hear the charcoal break, crack and crumble underneath the performing body. the sound extending the drawing action, lifting it off the surface. Charcoal lends itself to movement and duration with subtle and intricate possibilities for marking, embedding, imprinting, smudging, and layering. In this situation, however, sound and material resonances of charcoal were muted. Missing much of the textural and sonic complexity between charcoal and paper that normally folds back into the live process, the lack and sparsity of this configuration reveals other things.

L o w

The accumulation of charcoal lines gradually formed a material coating on the tracing paper as the moving body pressed down, brushed and rolled over them, allowing less light to filter through the paper-glass and reach the lens of the documenting camera below. The bare skin, too, became coated with a thin layer of charcoal. As the bodily shapes in the video become increasingly dark and flat, the moving body becomes increasingly embedded in and as surface/screen. Any visual hierarchy between body and surface — through relations of above, behind and below — seem to collapse. And although the body was elevated on the table platform, there is no sense that it is occupying a higher place. It remains low in order to maintain contact with the paper/screen and to offer evidence of its presence. And on the platform/paper/screen the moving body twists and rotates around, offering no sense of up/down, right/left, north/south or east/west orientation.

The visual presence of the body moving around in darkening surface-traces accentuates the stillness of the surface as it receives and is animated. In contrast to my other drawing processes with charcoal, little sound is picked up on the recordings due to the hard, smooth and non-absorbent paper-glass, the rigid metal construction, and the body’s careful navigation on the platform’s small surface area. The little sound that was generated by the body moving, breathing, or the charcoal breaking was unable to be recorded by the camera's microphone through the thick glass tabletop. The absence of sound perhaps further isolated the visual information from the actual material encounter, generating an additional distance to a sensation of weight — as well as quietening the expressive performer presence.

S h e

During the research, I developed a mode of note-taking to describe the working situation on the elevated platform from the perspective of the moving-drawing body. This methodology recorded my observations as the performing body but written in the third person by the choreographer: she.

These observations give a layer of information that is not visually evident on the video recordings taken from underneath the translucent screen. The camera from above documented an overall view of the installation with its configuration of bare body, table-like construction, translucent paper-glass tabletop, and concrete floor. This bird’s-eye view offered a stark contrast to the softer muted imagery recorded below and the bare body seemed overly exposed and present as a naked performer, which distracted focus away from the reciprocal touching between surfaces of paper and skin. Furthermore, the material encounter involving weight, gravity, and sensation is not actually present in either recorded view, whereas the she mode of writing can perhaps bring the reader/viewer closer to the material surface and low orientation to the ground.

Using she, I could describe what was becoming evident to the moving body on the paper-glass platform. I used a descriptive, observant voice to report on the processes of doing and performing in the present tense, drawing on embodied knowledge to understand the context of the installation; a sensing-thinking voice that stayed as close as possible to what she was noticing in terms of material and physical actuality, rather than that which was imagined or desired. The she mode was able to linger and suspend the gap between direct transfer of weight and digital transfer of data, between performing and spectating perspectives and proximities, and offer another kind of orientation.

In stilling and slowing her body, she notices miniscule shifts and drops of weight, residue sensations of paper-glass pressing the body or a lighter delicate touch as skin brushes paper. On rising she notices an accentuated sense of uprightness through the spine,

A q u i e t p r e s e n c e

Considering drawing in relation to movement as ephemeral and trace as a materialisation of movement often means that drawing is associated with an absent body. By shifting attention to surface contact and surface dimension, this research has led me to consider the ways in which a performing body is present rather than absent. The discussion, therefore, has been more around presence, particularly proposing and working with a co-presence of materials, bodies, and objects.

In considering human and non-human forces within choreographic practice, I was able to emphasise the conditions of performance rather than performances as simply expression, which has wider implications for our contemporary working, making, and living. The research suggests a particular value to a quiet position in the world that gives space to observe and be co-present. To be quietly present — not in the sense of less present but in the sense of less isolated from other things, to be equally present with them.

E x t e n d i n g a c h o r e o g r a p h i c v i e w

Reflecting here in the bottom right hand corner of this exposition, I remember the sensations of working on the platform and paper-glass surface, windows open right and left, hay fields outside and the large empty studio accentuating my elevated work-space of 2m x 2m. In the two weeks at L'Animal a L'Esquena I developed an understanding of the time-space of the square surface-area that was being generated from different perspectives as performer, choreographer, and viewer.

I reflect on how my notion of intersect became increasingly effective as a practical research strategy, that moved through and complicated the relations of bodies, materials and surfaces that were presenting in the practice. Intersect became a conceptual skin and screen generating a descriptive mode of note-taking so that the philosophical themes could take shape from within the conditions of moving, drawing, and recording the table-like construction. This allowed me to interweave the practical and theoretical aspects of the Translucent surface/Quiet body and to experiment with and re-evaluate Steinberg's 'flatbed' within a hybrid choreographic field.

This exposition and the wider project of developing a choreographic view of drawing proposes performances, processes, and presentations across surfaces of paper, screen, floor, wall, projection, and skin. The different yet coinciding views seem able to present complications of what body is and what surface is - allowing things, understandings, or perceptions of material, visual, graphic, and haptic information to overlap, meet, complicate, and slip between, layering relations between what is seen, felt, heard, remembered and understood.

Approaching drawing from a choreographic view contributes to current practices, discourses and manifestation of materials, things, and objects in performance. By considering the moving human body as one material among other materials, one object among other objects, one surface among other surfaces, different kinds of compositional strategies can evolve and other kinds of choreographic practices and knowledges can emerge:

There has been a shift to material, to co-presence, to low, to quiet - and these shifts have appeared on the surfaces of practice.

R e f e r e n c e s

Allsopp, Ric, ‘Still Moving: 21st Century Poetics’, Ungerufen: Tanz und Performance der Zukunft/ Uncalled: Dance and Performance of the Future (Berlin: Theater der Zeit, 2009), 247–255.

Alpers, Svetlana, The Art of Describing; Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century (Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press, 1983).

Berger, John, Ways of Seeing (London: Penguin Books, 1972).

Blades, Hetty, ‘Affective Traces in Virtual Spaces: Annotation and emerging dance scores’.Performance Research, 20:6 (2015), 26–34.

Connor, Steven, The Book of Skin (London: Reaktion Books Ltd, 2004).

CONTACTQUARTERLY.COM, 2009, <https://contactquarterly.com/contact-improvisation/about/> [accessed 11 November 2017].

Eeley, Peter (ed.), If you can’t see me: The Drawings of Trisha Brown in Trisha Brown. So the audience does not know whether I have stopped dancing (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2008).

Florêncio, Joao, ‘Enmeshed bodies, impossible touch’. Performance Research, 20:2 (2015), 53–59.

Forsythe, William, Choreographic Objects, 2008, <http://www.williamforsythe.de/essay.html> [accessed 11 July 2018].

Harman, Graham, The Third Table, doCUMENTA 13/100 Notizen (Bremen: doCUMENTA(12), 2012).

Heathfield, Adrian, ‘In Memory of Little Things’, La Ribot, ed. by La Ribot, Marc Perennes, Luc Derycke (Paris and Gent: Centre National de la Danse, Pantin and Merz/Luc Derycke, 2004), 21–27.

Jones, Amelia & Warr, Tracey, The Artist’s Body (New York: Phaidon Press, 2012).

La Ribot, Despliegue, 2001,<http://laribot.com>.

Lepecki, André, Exhausting Dance; Performance and the Politics of Movement (New York and London: Routledge, 2006).

Manning, Erin, Politics of Touch; Sense, Movement, Sovereignty (Minneapolis & London: University of Minnesota Press, 2007).

Nancy, Jean-Luc, Corpus (New York: Fordham University Press, 2008).

Pallasmaa, Juhani, The Eyes of the Skin, Architecture and the Senses (London: Wiley-Academy, 2005).

Paxton, Steve, Material for the Spine; a movement study [DVD] (Brussels: Contredanse, 2008).

Peeters, Jeroen, Through the Back, situating vision between moving bodies (Helsinki: TEAK Theatre Academy of the University of the Arts, 2014).

Peter, Luc, La Ribot Distinguida [Film], 2006, <https://vimeo.com/77062512>.

Steinberg, Leo, Other Criteria: Confrontations with Twentieth Century Art (New York: Oxford University Press, 1972).

SYNCHRONOUS OBJECTS.OSU.EDU <http://synchronousobjects.osu.edu> [accessed 6 July 2018].

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2017, <http://metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/265347> [accessed 12 December 2016].

She moves with increasing understanding of her situation and what is being generated for the documenting camera on the other side of the paper-glass. She learns how fluidity, pressure, touch, withdrawal are translated into visual data of darkness, light, form, and line. She becomes increasingly aware of how this affects her and allows her to investigate a quietening body.

She draws with a charcoal stick in both hands, working with one or both, combining techniques of outlining body, extending line, leaning into, balancing on, suspending weight, twisting spine, sliding skin, rotating around, finding ground, exploring edge of body and platform. She notices how her slow, smooth movement follows a spiral path to standing, allowing her eyes to briefly scan the space before sinking back to the paper-glass.

line into movement and movement into line

line emerging on the surface and disappearing into air

F i g u r e s

Figure 1: Man Ray, 1922, Rayograph; Comb, Straight Razor Blade, Needle and Other Forms, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York [online] <http://metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/265347>.

Figure 2: Rauschenberg, Robert & Weil, Susan, 1950, Female Figure, Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York [online] <http://www.rauschenbergfoundation.org/art/artwork/female-figure>

Figure 3 and 4: Forsythe, William, 2009, Synchronous Objects, for One Flat Thing, reproduced <http://synchronousobjects.osu.edu/content.html#/NoiseVoid>.

Figure 5: Rauschenberg,Robert,1995, Bed, MOMA, New York [online] <https://www.moma.org/collection/works/78712>.

Figure 6: Pollock, Jackson, 1950, One: Number 31, 1950, MOMA, New York [online] <https://www.moma.org/collection/works/78386>.

Figure 7: Rauschenberg, Robert, 1953, Erased de Kooning, SFMOMA, San Francisco [online] <https://www.sfmoma.org/artwork/98.298>.

Figure 8: Man Ray, 1920, Dust Breeding, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York [online] <http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/69.521/>.

Figure 9: La Ribot, 2001, Despliegue <http://www.laribot.com/work/18>.

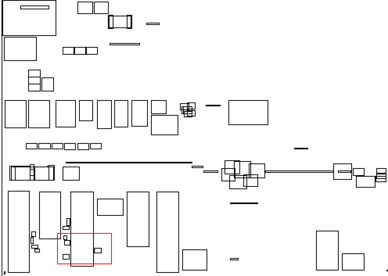

Figure 10: K.Brown, Translucent surface/Quiet body, redistributed, Research Catalogue 'navigation map' [screenshot 30 August 2018].

Figure 11: K.Brown, Translucent surface/Quiet body, redistributed, Research Catalogue 'navigation map' [screenshot 22 April 2019].