The interior: survey

As the narrative leaps forward in time, the genre-space is redefined. While the previous chapters have been located in uncharted nature, the space of the antiseptic, hermetic white laboratory plays off the classic tropes of science fiction and uses certain devices to create a futuristic setting. Complex theoretical language is introduced that is drawn from contemporary aesthetics, politics, and other literature to create hybrid technological and scientific principles. It is a common strategy within SF, in which the familiar is displaced slightly and transports the reader to a different world through what Darko Suvin has described as a ‘novum’.[1] While the novum is usually something technical or social – a cognitive displacement of the things around us, in this text the nova are a series of compressions between aesthetic terms employed within a ritualised science.

The fantastical is an inherent part of science fiction’s genre-space. We frequently see the two merge in popular culture – ‘sci-fi and fantasy’ is commonly used as a singular classification within libraries, bookstores, cinema, and online. The fantastical appears in this section most particularly through frequent references to Lewis Carroll. Contemporary rational science of the laboratory operates in a near abstract realm, working with microscopy, molecular or sub-atomic studies that are outside the sensible. As such, it requires certain leaps of imagination that appear counter-intuitive or even nonsensical. Carroll’s fantasies are passageways into the questioning of representation and knowledge and its limits, in particular through mapping of the world. Mapping always fails to represent fully. In fact, it is only valuable if it has the right amount of information. Too little information and it is not useful; too much information and it becomes redundant. Carroll plays with the interaction of different dimensions – in particular the two dimensions of the page with the three dimensions in which they operate. Here I also refer to another branch of science fiction, or perhaps more accurately ‘geometric fiction’ – Edwin Abbott’s Flatland, a Romance of Many Dimensions (1884). It reframes discussions of transcendence downwards, to imagine life as a two-dimensional being that suddenly becomes conscious of three dimensions. It is a social satire akin to H. G. Wells’s The Country of the Blind (1904). Both demonstrate superior vision as being beyond the comprehension of the masses, who judge it a form of madness and seek actively to neuter such unconventional thoughts.

Back to Chapter two - Go to Chapter four

[1] ‘Sci Fi is distinguished by the narrative dominance or hegemony of a fictional “novum” (novelty, innovation) validated by cognitive logic’, Darko Suvin, Metamorphoses of Science Fiction: On the Poetics and History of a Literary Genre (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1979), p. 63.

The interior: landmarks

The odd grammar and logic of the title ‘nostalgia for the future’ could indicate that the future is dead, or that we are laying down things to be nostalgic for when the future arrives. In that sense, it looks in two directions through time. In particular, the chapter reflects on the third space of the exhibition, which presents Yu-Chen Wang’s ‘Heart of Heart’ commission. The work is itself a science fiction of sorts based around a printing machine in the Manchester Museum of Science and Industry where machine parts play conscious roles. Its aesthetics are drawn from early literature and cinema where the future is imagined using the technology of the time.

Superficially, the chapter appears to follow the imagery of science fiction. In this essay, novum is created through items such as the bubble house – a futuristic structure common in twentieth-century literature, which now seems a relatively quaint vision of what is to come. Drones and scanners are equally common today, but still appear futuristic when presented in today’s science fiction. Alternatively, some of the still-yet-to-come tropes might be seen as retro-futuristic – that is, of a past future, a nostalgic image of what might be to come, and a longing for an imagination now lost. It is widely discussed that retro-futuristic aesthetics have come to be the model of today’s actual technology.

However, the underlying themes of the chapter address the potential of language to represent the world, its absurdity, and its inevitable abstract character. It is in this merging of text and reality, or information and experience, that new worlds are constructed.

The team are employing a kind of novum from the curatorial ‘Warburgian scalar intellectual transformations’, suggesting the merging of aesthetics, ritual, and science, in partial homage to Aby Warburg and his legacy. Warburg’s method in utilising his library to chart out ‘flights of images’ can be said to view works of art as information. His pathosformel traces out emotional language that passes from one period to another in gestures and images.

Analogies appear for meta-data analysis in which the tools of recording are analysed as well as the subject itself, a science of looking at patterns beyond the surface that structure the visible or apparent.

The map is a direct reference to The Hunting of the Snark by Lewis Carroll. Carroll’s fantastical writing is often based in how logic might become absurd. While renowned as an author, Carroll was also an Oxford don of mathematics and logic. The map in The Hunting of the Snark is one example of the tensions between representations of the earth based on the language of mathematics and the unknowable nature of experience.

Mapping and its limits not only are part of the narrative but also are represented in the exhibition through the presentation of drawings on table tops, as well as in frames on the wall. The change in plane of viewing seems to allude to the shifts in scale between experience and overview or abstraction. Additional references to Carroll also appear through the narrative through character names and shifts in scales.

We might consider mathematics as a language in one of its purest forms that transgresses cultural associations. It is communication, on the one hand, or an image, on the other. Communication technology, both futuristic and archaic, is deployed as Wang’s recent commission for the Manchester Museum of Science and Industry, which considers the life of language as an image – giving personality to the ‘linotype’ itself. Energetic particles, the material of type, and the steam-powered machines are personified in the work, turning mechanics into a metaphor for social relations. This is furthered in the reference to Abbott’s novel Flatland. The triangular costume from Wang’s performance and other resonances with the narrative – itself a kind of science fiction – are brought together.

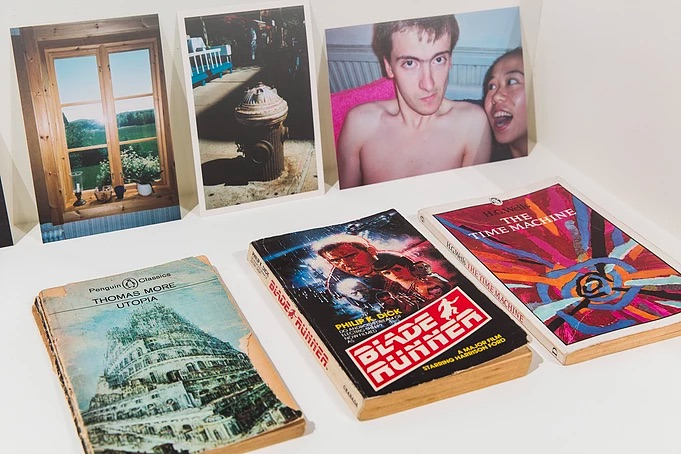

In contrast, Bruegel's The Tower of Babel adorns the cover of the Penguin edition of Thomas More’s Utopia and is presented in the archive display within the gallery. This choice of imagery is particularly relevant, if seemingly discrepant. While More’s island of Utopia is seen as an idealised political system as a critical address to Europe at the time, the Tower of Babel is a result of hubris that causes the division of people.

unknowable oceans of fear and aggression combined in one. The voice that spoke from behind them was unintelligible to me word for word, yet I comprehended its tone and intent fully. Holding up a fruit to my mouth it insisted that I tasted the flesh of the island and so I yielded in obedience. It was sweet and fresh, quite distinct from the reconstituted provisions in the bubble. Even the hydroponically cultivated fruit I had occasionally experienced in the city-state were pale in comparison. Despite this, its perfume evoked a confusion of warm memories of a home that was not my own, and the embrace of a family that I had never had. Beneath these lay the long extinct sense of hope for shaping a future. Those eyes continued to hold my attention while hands reached round my neck and tied a string on which an object hung against my chest, seeming to radiate a romantic sentimentality. The machine in the background began to whirl more quickly, speaking in its own punctuated beat. Then I felt cold Marbaline again, this time on my cheek and found myself prone with Alice leaning over me. She held my head, urging me to drink from a small vial. As soon as the bitter tang of the liquid ran over my tongue I was brought back to earth with a jolt.

acquire from the nineteenth-century crew’s effects. A diary entry, it told of a time they had been lost at sea. Their vessel, the Saudade, had been engulfed by fog and drifted in the doldrums. They navigated using a blank sheet of paper bounded by the ordinals. With only a compass to guide them, scale, distance, and location had become abstract concepts. I identified with this as I moved to look at a model sitting alongside. It was a model of our own bubble that was included in the life-matrix of the island according to standard ethno-biological protocol. Every detail of the interior was reproduced precisely, from the grain of the Marbaline floor to a model of this same model in such high definition that it created a sense of vertigo to look into it. ‘Good’, said Alice as she saw me lost in imagination. ‘Pascal had always told us that “the last proceeding of reason is to recognise that there is an infinity of things which are beyond it”. Push past into that infinity and search outside yourself.’

I have to confess that this blended science and mysticism usually brought about such a wave of cynicism in me that it would displace me from any deep meditation. But this time I found it within my grasp to transcend the flatland of reason and see the constellation of objects as something

silence it was not to tell Alice what I had seen but to lead her to her wonder on the things she had gathered, to see them as a vibrant searching community in itself, an organism not a tool. Under my encouragement, Alice and her team became children encountering something new for the first time – that is, playing. Instead of asking what the things on the island did, they started to ask what they could be.

With this simple act I became the medium for this communicable pathogen of social space we call Janus. Up until then it had been conceived that language may be emergent as part of natural processes of evolution, but biology remained prone to the physical transmission of evolving genes alone. Distracted by the fear of technology overrunning with its informational viruses, no one since the fall of Babel had considered what might happen if it was language itself that could be infected by exposure to those of another place or time. Pidgin vernaculars became chimeras that changed the very matter of our minds, thereby invading our bodies. Words as images, distorting our brain chemistry and releasing latent dreams of what was and will be. This infection was a search for hope, driving us to become discontented with their lot, and to rebel against the dictum of ‘stay thou in your place’ that had become the mantra of our supposed civilisation.

sheet of writing paper, and some human remains all bleached from the sun. But there were no permanent structures showing on the satellite surveys, and the electro-plane had dropped our field laboratory in a clearing far inland where no one seemed to have ventured. As a working team we had been appointed on behalf of the governing corporation whose name I will not mention here for fear of breaching a contract that I have still yet to fully read. The main point of the contract was to sign over anything I saw, discovered, or even thought about as their property. In the eight-person team, the appointed team leader was named Alice. An expert in Warburgian scalar-intellectual transformation, her work was groundbreaking, but she was a prickly character. In fact, the whole team were reclusive at best. Contract and team members alike certainly dulled the impetus to put energy into the study rather than simply sit out the contract period, although there is only so much time one can spend in a sterile climate-controlled environment without starting to hear whispering voices.

It had been deemed that any solutions found on the island would be deciphered by quantum hybridisation. My own expertise was in nuclide microscopy cultures, a far cry from

Chapter three: the interior

The nausea arrives with seeing double. Not two things at once but two times. That is why we named it Janus.

We had spent almost three weeks on the island. Most of the time we remained within a perimeter of scorched earth that exposed the copper threads in the ground. Mainly we were confined to the interior of the bubble structure, and when we did venture outside it was in hermetically sealed suits. Using a drone scanner we could survey a little further. Its scanners mapped the copper back to its point of origin that lay over the mountain’s ridge. But that was beyond the range of the drone’s capabilities so we couldn’t get any visuals. Regardless, our purpose here lay elsewhere, a study of the supposedly untainted genetic codes of plants and animals in the hope of reinvigorating our own depleted stocks.

As far as we knew the only people to set foot on the island had done so more than a century earlier. We had come across some items that were too far in land to be carried by the sea. Among them was a section of faded carpet, the occasional

this new science. So during the broad vision survey using a ritual algorithm, I was somewhat lost for method and had to go with the flow. Dressed in the ritualistic modern science garb of grey flannel cut in a triangular poncho, Alice laid out a series of points of view mapped onto objects that related to the island to form a complexity map marking out the empty niches that we aimed to fill in. Many of the objects on display – drawings, books, letters – were familiar somehow each reminiscent of old linear taxonomies whose progressive evolution was redundant.

‘When the tool is most a tool, it recedes into a reliable background of subterranean machinery. Equipment is invisible,’ Alice pronounced to lead us into the group analysis. While the whole team nodded in agreement, I suspected the others were as puzzled by the poetics of contemporary biological discourse as I was. Its reliance on language to constitute everything into being didn’t always gel with the reality of the chemicals I observed through the microscope. But such was the current trend and one had to keep up with times. I was drawn to a small scrap of paper, yellowing with age and ink running from years in the jungle. It was one of the few artefacts we had managed to

more than its constituent parts but linked on micro and macro scales. My own pulse was interwoven with those of the machinery that surrounded us like a fractal helix. The air conditioning’s hum, the oxygen scrubber’s ticking, the dripping of condensation on the outer wall of the bubble, and finally into the surges of current that flowed in waves through the copper network of the island’s peculiar natural wiring – all seemed in tune. The disjuncture between spaces of perception made me giddy and soon I vomited as if trapped on deck in a heavy ocean swell. This was seen as a positive reaction and my colleagues began to move in rhythmic dances and make chanting calls in support. What was real and what was imagined no longer mattered as I was transported elsewhere.

My feet were the first to return to earth, but the cold Marbaline had been replaced by soft grass. The dry air was now a damp must, and the low hums of hidden filtration systems replaced by the heavy thud of machinery. In this place nothing was sterile. Everything was caked in dirt and grease, plants wound through buildings, tools, and insects seemed equal in their work. People moved around me, but only one of them held my gaze. All I can recall about them is that their eyes evoked dark pools of sympathy and

’What did you see?’ she asked, but I was not ready to share the vision. Quite distinct from a dream, the memory didn’t fade but remained firmly lodged in my mind. Those dark eyes seemed to continue to look at me. I felt like I was studying myself in a mirror somehow. The return to the here and now was like falling from a tower, torn from the seamlessness of language in its purest form. So I remained silent until I could collect my thoughts, protecting this secret. And until I agreed to speak, the team put me in an observation unit, I suspect, to protect the company’s property as much as to protect themselves. But ideas cannot be contained by hermetic seals and air filtration units.

Alice visited daily until I finally spoke. Between her visits I watched her and her team continue their ritualistic experiments as they tested their theories by constantly rearranging the reference objects in new combinations and reperforming their methodologies. But there were no further incidents like my own, and I once again become reaccustomed to the world as I knew it. Nevertheless I continued to imagine a new one. What the team seemed to miss was not the answer to a question, but the acceptance that the question has no answer. So when I finally broke my

The interior: field notes

As an aside, it has subsequently been proved that ‘time crystals’ exist that are symmetrical across time rather than across space. The interrelatedness and contradictions of the experiences and behaviours of time and space have been a constant in science and science fiction alike.

Yu-Chen Wang has used performance based in science fiction and traditional Taiwanese ritual on a number of occasions. The ritual clothing is based on her costumes that hang in the space, while the dance is taken from a performance during the opening. The ritualistic reading is based on aspects of traditional Daoist funeral rites, reflecting a cultural approach to the ending of life whereby the deceased returns to the family.

The quotation is taken from Graham Harman, the foundational thinker in object-oriented ontology. Here it is dislocated from that philosophy through its own descriptive power to echo the island’s wires and movements. Harman’s writing considers all objects, be they living, inorganic, or humanmade, to have the quality of tools, in that they become visible when they break from their use and take on new characters. In this respect he invests the inanimate with a beingness of its own.

This playful act, moving from what a thing does to what it could do, is taken from Huizinga’s Homo Ludens and is at the core of creativity, particularly present in Wang’s practice that dislocates objects from their use and ‘animates’ them. In essence, it asks them what they can do or be, rather than what they are designed to do. This aspect is akin to Harman’s critique, that objects only become visible when they break from their tool-like qualities.