3. HISTORICAL MUSIC CONTEXT IN CORDOBA, MIDDLE XVIII CENTURY.

In Spain, at the middle of XVIII century the main musical activities revolved around cathedrals. This institutions not only provided an education but also a daily meal, attracting children from various social classes who aspired to become professional musicians.

Music also played a significant role in city celebrations; either annual festivities or in the honour of the monarchy, and the cathedral spared no expense in supplying the chapel with the best musicians.

Córdoba was a well-connected city; like other activities, music was an integral part of the city´s atmosphere. It may surprise us today how well-informed individuals were in the middle of the XVIII century about developments in other Spanish cities and Europe, including musicians and compositions.

Among all the churches and chapels, the cathedral had the most money to invest in music, and therefore had the most prestige. Not only were masses accompanied by music, but weddings and royal baptisms as well. Music played a prominent role in all these events. We can gain insight into the musicians and their salaries from the catastro (cadestre) of 1752, in Córdoba. This document provides comprehensive information about the instrumentalists and singers who offered their services at Córdoba Cathedral. This large and diverse group participated in the processional parades of Holy Week and other religious festivities or masses.

Despite the scandalous deficit of the Córdoba city council in XVIII C, it provided fixed amounts to subsidize the cost of certain religious festivals celebrated in the city. Among the most significant is the Corpus, San Roque, San Sebastián, and others, all accompanied with music during the processions.

Concerts not only took place in the cathedral or churches, but also in the halls of the nobility, likely performed by the same musicians from the Cathedral. This phenomenon was not exclusive to Córdoba but occurred generally in most Spanish cities and even beyond, in the America colonies. These events were highly lucrative for the nobility, and musicians often preferred to forgo their day jobs at the cathedral in favour of the substantial increase in earnings from these concerts. Maestro Gaitán y Arteaga himself, during his tenure in Segovia, lamented that musicians often neglected their obligations by performing at private parties:

Juan González Gaitán, maestro de capilla, complains that some

musicians go to private parties dismembering the chapel. Musicians be warned that they cannot do it, and that they must always inform the chapel master of which parties they are invited.

3.1 Theatre in Córdoba

The city of Córdoba had a theatre where performances could take place. Representations were held in a theatre near convent of Carmelitas Descalzas de Santa Ana. However, the theatres were closed and performances were prohibited in the south of Spain from XVI century and until the middle of XVIII century, as the Catholic Church held a stance against theatres and other performing arts. Rulers, fearful of the perdition of their souls supported the prohibition. However, it is also known that some amateurs organized clandestine representation behind the law. Only in 1871 a new theatre was built in Córdoba, which was initially called Cómico and later the Teatro Principal. This became the most charismatic and significant building in Córdoba in terms of the quantity and variety of genres represented during the XIX C. Subsequently, more theatres were built to meet the growing demands for cultural activities in the city.

3.2 Opera

Opera repertoire was welcome in Spain during XVIII, even being sponsored and supported by the authorities. Opera was favoured by Felipe V and Isabel de Farnesio who had a preference for Italian opera. This model was seen as a means of promoting moral and educational regeneration among citizen. The reality in Córdoba differed from the rest of Spain. Opera buffa arrived in Córdoba on 1767, with performances held in the Royal Sites, where this type of entertainment became more common in Spain. We can verify that in May 1768 the Stalianoz Opera Company requested a license from the Cordoba Cathedral to use their musicians for operas, as the company did not have instrumentalists for it. However, the city hall denied this request, starting "the determination of this plea be suspended until a more opportune time". Nevertheless, in 1783, representation of zarzuelas, tragedies and Italian and French pieces were authorized. With the earlier prohibition of comedy, as mentioned, Córdoba had to wait one century for more opera performances to be staged.

In this situation, I would assume that the performances at the cathedral, which took place during important festivities such Christmas, Holy Week, Corpus Christ, and the Immaculate Conception, among others, had a great expectations from the citizen; especially the villancicos composed in the vulgar language understandable to the entire population.

3.3 The music chapel

The music chapel was composed of singers and instrumentalists conducted by the Chapel Master. Whether performing inside or outside the Cathedral, they wore cloth cassocks, surplices and caps. Outside the temple, they sometimes, added a cape and a three-cornered hat to their cloth cassocks.

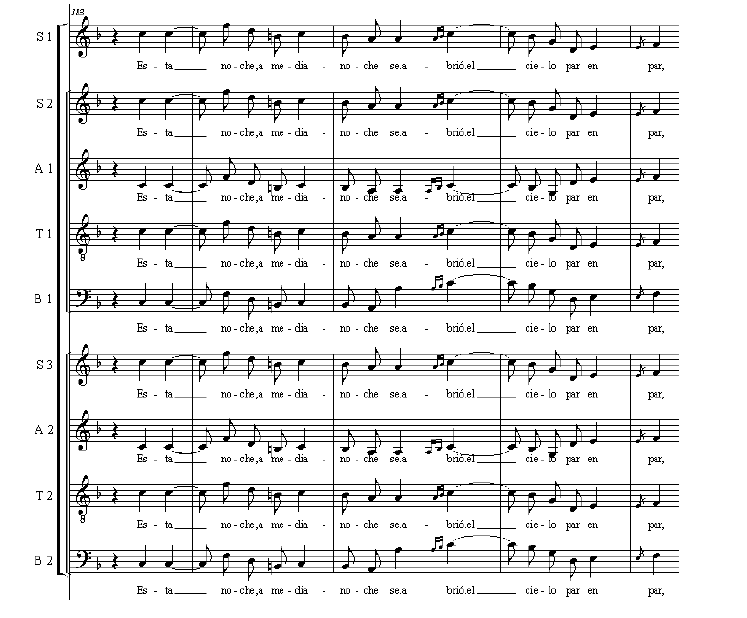

To better understand when the music was performed in the chapel, it is important to consider the repertoire sung in the cathedral. On one hand, there was the so-called plainsong, written in square notation, on five lines or staves. It had been sung since medieval times and was interpreted solely by the sochantres, chaplains and accompanied by the organ. On the other hand, there was an an ensemble consisting of a choir and soloists.

3.3.1 The Chapel Master.

The Chapel Master was the musician who required the most preparation. He had a deep understanding of the pieces and various composition techniques. He composed the music en papeles for various required celebrations and festivities. In addition to composing his own pieces, the chapel master conducted and rehearsed with the musicians of the Chapel. Juan Manuel Gaitán y Arteaga was the chapel master in Córdoba Cathedral from December of 1752 till October of 1780. Gaitán y Arteaga obtained this position by appointment. The city hall of Córdoba was familiar with him, as he had been a singer in the chorus when he was a child. Gaitán y Arteaga personally auditioned all the vocalist and instrumentalists who wished to join the Chapel. From 1752, Juan Manuel began traveling to different parts of Spain to recruit musicians to play and sing in Cordoba. He particularly focused on finding sopranos and altos, which were very difficult to find in Cordoba.

3.3.2 Choir of the Cathedral of Córdoba.

The first law that regulated certain aspects related to musicians in Córdoba Cathedral was the so-called Estatuto de Pérez Contreras, in 1430. However, the first regulation that directly impacted the organization of the music Chapel was Los Estatutos de la Santa Iglesia de Córdoba by Fray Bernardo de Fresneda in 1577. This law, documented the musicians of the Cathedral at that time: a chapel master, two child boys and two organ players, a tiple (the highest voice), a contralto, a tenor, a double bass, and an organist. Specific regulations for musicians were formally written down in Constituciones y Reglamentos que deben observarse el Maestro de Capilla, Músicos y Cantores de la Santa Iglesia de Córdoba in February, 1601. A century later, on March 30th of 1704, Felipe IV ordered the creation of other constitutions to regulate the situation of the musician in Córdoba cathedral (Constitution y Estatutos que su Católica Majestad Felipe IV, nuestro señor, mandó hacer para el buen gobierno, y servicio de la Real Capilla de él, sita en la Santa Iglesia Catedral de Córdoba)

The organizational scheme of these laws were maintained in the following centuries. The changes that took place were related to the increasing number of vocal and instrumental musicians. The most noticeable increase was in instrumentalists due to the difficulty of finding good voices, especially tiples, and contraltos. Consequently, the cathedral hired instrumentalists who could compensate for the lack of these voices. When Juan Manuel Gaitán y Arteaga became maestro de capilla in Córdoba in 1752, there were 10 singers in the Chapel: 2 tiples, 3 altos, 3 tenors and 2 basses. When he retired in 1780, there were 17: 4 trebles, 3 altos, 6 tenors and 4 basses.

3.3.3 Members of the choir and instrumentalists

Tiples.(the soprano voice of a boy) or Soprano.

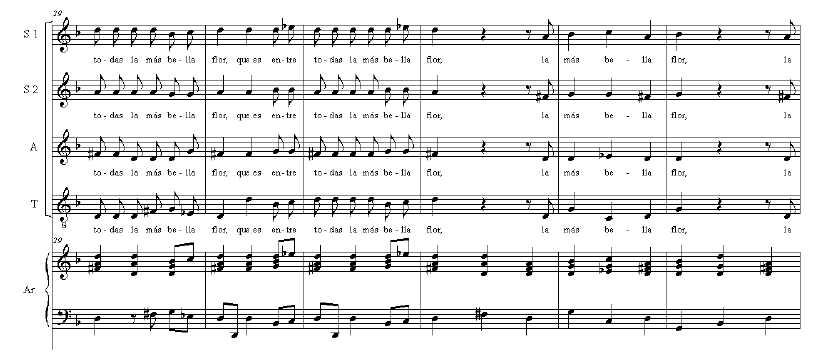

The tiple was the highest voice in the choir and the most difficult to obtain because the candidates had to be castrated. They were paid a higher salary than other singers, as a general rule, they had to be found outside of Córdoba. In Juan Manuel´s villancicos the treatment of the text in this voice is typically syllabic and melismatic at the end of sentences. Great melismas appear in the arias, many of which coincide with long progressions. There are abundant high technical demands such as ornaments, fast figurations and jumps, sometimes with intervals that are difficult to sing.

Altos

Tenor

The tenor voice was used as a soloist in some villancicos, alternating with the soprano voice and it moved in a very broad register. In Jardinerito del Huerto Cerrado where the tenor sing jumps of 4th, 5th and 8th. Their relationship with the text is usually syllabic, except for solos where melismas may appear at the end of the sentence and coinciding with the accent of the word.

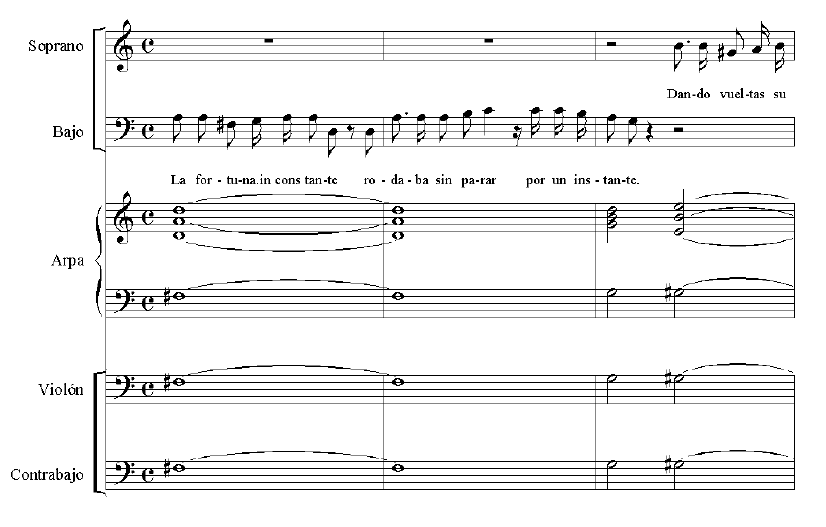

Bass

The bass voice was the lowest voice in the chapel. This voice was also called double bass. It was sung by the sochantres (conductor of the choir). The bass voice is not used as frequently as the others, since the villancicos were composed for choir of two tiples, alto and tenor. Although, Juan Manuel use this voice as an exception in Venga el bárbaro Otomano, in which it was composed for a soprano and bass that sing solo and in a duet.

Instrumentalists:

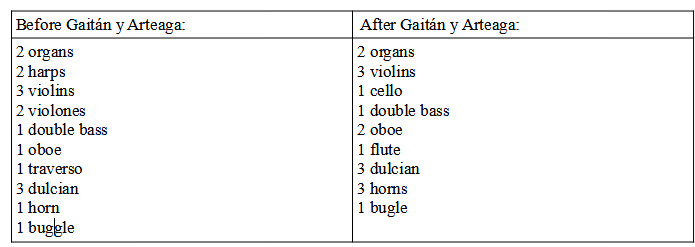

The instrumentalists began to play in the Cathedral later than the singers and were incorporated into the music chapel around January 4th of 1528. They were hiring occasionally and gradually became part of the music chapel. At this time, most instrumentalists knew how to play more than one instrument and this was a point in their favour when they were hired. When Gaitán began as masestro de capilla in 1752, there were a total of 10 instrumentalists in the chapel (see table below). When he retired in 1780 there were a total of 15 instrumentalists (see table below).