5.5.2 Walking Contención Island

The incremental nature of the works in this thesis led up to and catalysed the creation of this final work. Walking Contención Island was a series of three works in which I was working with all my categories of island walking, plus my experiences of embodied walking and replication. Following on from Alnay I created my second imaginary island through walking and marking out the routes walked. Then, as I had done on Papa Westray, Beàrnaraigh Mor and Alnay, I walked (a)round it, in a clockwise circumnavigation of its shoreline using random procedures to sequence my daily shoreline walks. In the third work I once more used random procedures, this time to identify and sequence the locations for recording the sounds of the island. This was also replication, in that the island, once created, was used again and again as a creative place.

Walking Contención Island became my response to the three periods of lockdown of the Covid-19 pandemic in England.1 The work evolved over the 12 months from the start of the first lockdown to the end of the third. Without the preceding island works in this chapter (and the works in Chapters 3 and 4) it would never have appeared in this form.

In the first lockdown I created Contención Island—my island of containment—by daily walking from my home.

In the second lockdown I walked the shore of my island.

In the third lockdown I walked to places and recorded the island sounds.

As I view them as a triptych, I describe the creation of the three works, and then their presentation.

The 42 walks of Contención Island

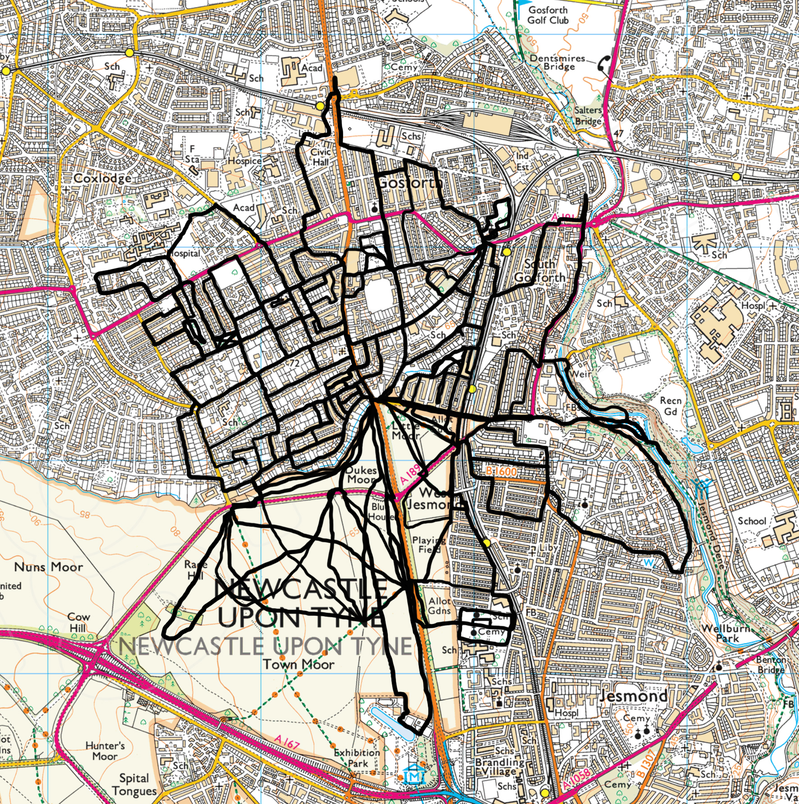

In the first lockdown the parameters for permitted daily exercise were never formally stated but I decided that I would be walking from and back to my home for around 60 minutes. I walked for 42 days (right) at different times of the day, spread from before dawn to dusk. Very early in this process I realised I was creating my second imaginary island.

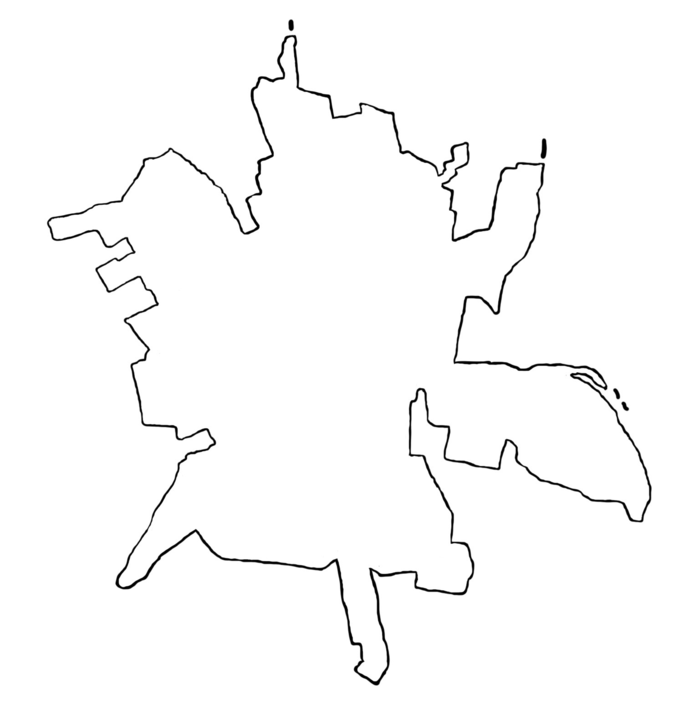

I recorded each day’s walk in a sound recording and in text. For the poetry I used a poetic form that I had not used before, the mesostic, a modernist/avant-garde poetic form (Brunton, 2018, p. 70) derived from the older acrostic form, and invented by John Cage.2 My use of the form allowed both a comment on my daily walk and a commentary on the emerging social and political events on each of the 42 days. However, driven by regulation and how far I could walk, it was my trace of the walks, that I incrementally drew on a map that, like Alnay, drew out a shape. With time it achieved a constancy, a coherence, a becoming of place ... a small island.

Whilst Alnay was my place of solitude and magic, an island that existed only for me as I imagined its shoreline, its cliffs, and its beaches, Contención Island was a place of isolation, an island born of imprisonment.3 Contención Island was irregular, indented and fissured—progress on the ground was shaped by the places walked through—cul-de-sacs stopped routes joining, as did main-road traffic or the local Metro rail lines while alleyways and cemeteries offered novel routes through. Thus, as with Alnay an island emerged, and the outline marked the shore of my lockdown world. Beyond was the uncharted.

The lines of the emerging island and the poetry were melded together into the first of what was to become a set of three scrolls. I also wrote a descriptive text that described my imagined island’s geography; this was presented at the end of the scroll. The writing and map together with the day’s sound recording were also posted daily on my blog (at https://martinpeccles.com).

A walk round Contención Island

At the start of November 2020 there was a second lockdown—an attempt to get infection rates down to allow an easing of restrictions at Christmas. Unlike the other two lockdowns, this was to be for a fixed time—28 days. So, having spent the first lockdown creating Contención Island I now decided to walk its edge, to walk the shoreline of the island, as I had done on the Scottish islands of Papa Westray and Beàrnaraigh Mor, and in so doing, to rebuild my island and thereby mark off the days of lockdown.

I produced 28 sections of coastline and walked one each day, clockwise. The order in which I walked the sections was determined by chance and over 28 days I rebuilt the island across time. Each walk was recorded in sound, poetry, line, and two photographs (the ground below and the sky above) and was again reported in my daily blog. The score, poetry and lines are presented again formatted as a scroll.

The photographs were formed into a composite for each day, and these were then formed into a composite circle image that encircled a line drawing of the island with the 28 segments; the images corresponded to their respective segments. This was included as an endpiece image on the scroll.

Walking to the Sounds of Contención Island

In early 2021 with hospital admissions and death rates again rising, England entered the third lockdown. There was no pre-prescribed duration, and at 83 days this was to be the longest of the three. During the first two lockdowns I had walked into being, and then circumnavigated, my island. In the third lockdown I populated the island with sound.

It did not feel interesting to record only at my favourite places and, given that I didn’t know how long this lockdown would last, it was possible that recordings could become repetitive if I recorded only at a small number of favoured places. Also, such an approach would not give voice to the sounds of much of the island. So, I again used the process that I had used in previous island works—determining locations by chance—and this resulted in the score.4

Each day I walked to that day’s island zone and recorded the sounds of the island. On previous occasions I had generated quite specific locations but for this work I chose the specific site within a zone myself, on the day.5 This was a practical urban adaptation of my procedures that I had used in previous works; if I had generated locations by chance then, unlike in a rural setting, large numbers of them would have likely been inaccessible—in the gardens of houses, inside houses or on roads and railways. Under these circumstances using random zones and choosing specific locations felt like an appropriate adaptation of my previous methods. I recorded each site in three ways—sound recording (described above), photographs and text.

I took four photographs—one pointing at the centre of the island, one pointing in directly the opposite direction, on pointing at the ground and one pointing at the sky—an act of orientation reminiscent of Kant’s views on needing a body to experience place, and the inherent sidedness of our bodies. From these I produce a single blended composite image for each day. These were then sequentially blended across the days. I wrote a poem about the experience of being in the place; the poems were edited onto the blended photo-images in the order of the days they were written. The photographs and poetry together with the score and the 83 recording sites were formatted as the third scroll.

Scripta continua

After the lockdowns where over, and after I had produced the scrolls, for each of the three sets of walks I produced a scripta continua (below). This was the lower-case text of the daily poems or, in the case of the first set of walks (The 42 walks of Contención Island), the capitalised text of the vertical phrase of each mesostic.

Presenting Walking Contención Island

I presented the works from Walking Contención Island across four radio broadcasts and one installation.

The first radio work was The 42 walks of Contención Island.6 With the given, fixed 57-minute duration, the composition was of progressive, sequential 80-second sections of the recordings moving across days one to 42.7 Each track was accompanied by a spoken word recording in two parts: first a sequential phrase from the text of the first scroll, and one line from the horizontal text lines of the days mesostic. The script is shown below.

The second radio work was A Very Random Lockdown: 42 days walking an imaginary island.8 Working with the same 42 sections as I had used in The 42 walks of Contención Island I randomized the order in which they appeared, to produce a ‘re-creation’ that had unsequenced time, a timeless limbo that felt like it matched the random, chaotic zeitgeist of the first lockdown.

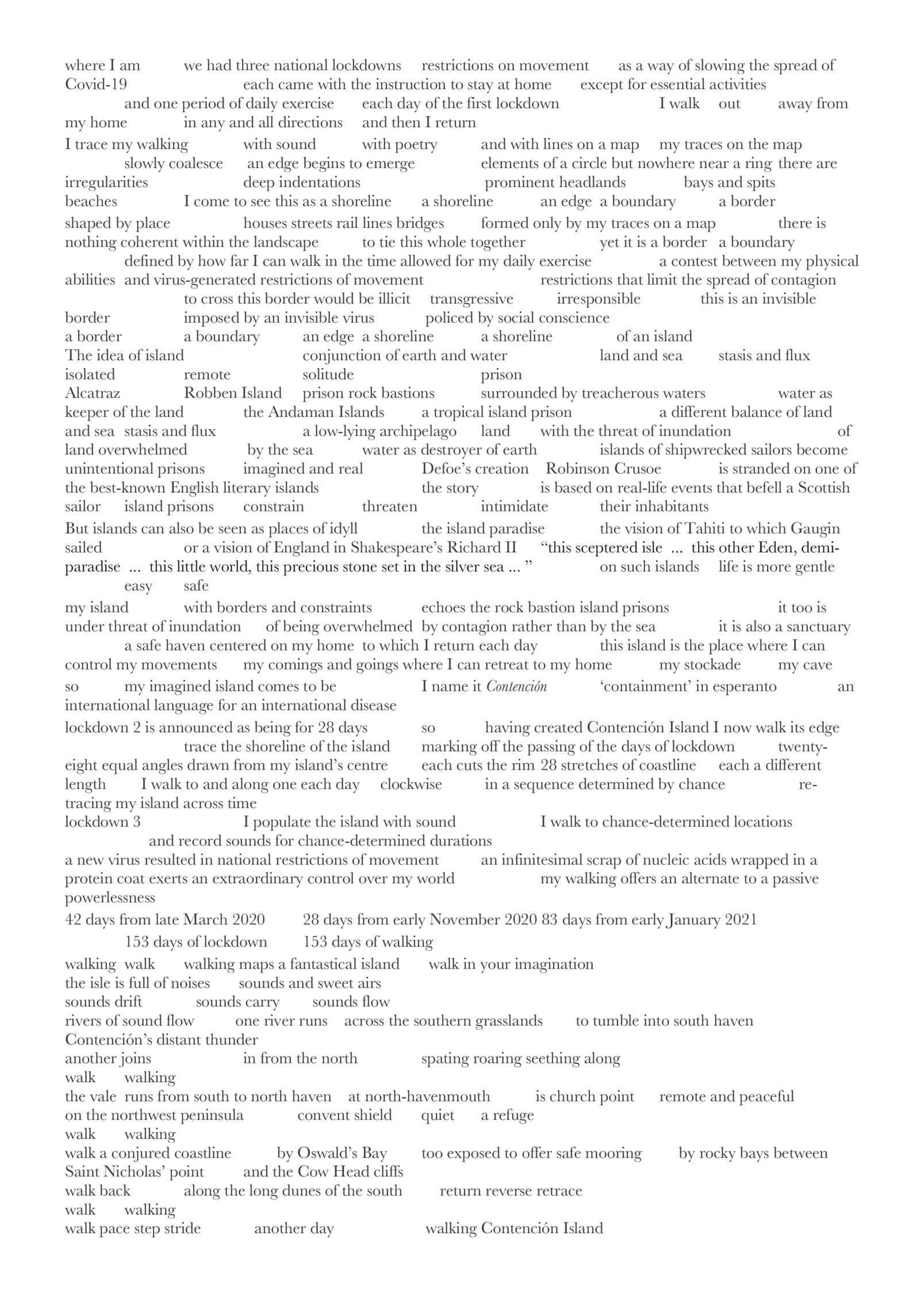

The third radio work, Walking Contención Island was based across the three lockdown works.9 Whilst the composition contained field-recordings from each lockdown, it was a prose poem in which I explored ideas of island-ness and how an island could be imagined (below).

The fourth radio work was A Walk Round Contención Island.10 This was a further experiment with presenting time and took all the field recordings from the second lockdown, which together lasted for over four hours and by increasing the tempo (without changing the pitch) fitted the composition into the broadcasters prescribed one-hour duration. Schaeffer discusses that, freed from being visually linked to the act of its production the acousmatic field is available for ‘varying the signal’ (Schaeffer, 2017), though this was, beyond volume changes, my only ‘varying of the signal’. My footfall became a rapid metronomic tapping running alongside the still recognisable sounds of traffic.

The installation Walking Contención Island presented the three sets of Contención Island walks together in the same (17 metres by 7.5 metres) space (below).11 Mono versions of the recordings of each of the sets of walks were played through three speakers; each corresponded to the text scroll that, laid out on the floor, stretched away from the speaker. The field recordings from the first work (The 42 walks of Contención Island) played continuously; the recordings from the second and third alternated until the end of the second work after which the third played continuously. The recordings looped every 15 hours and there was only ever a maximum of two speakers playing at any point. Each set of field recordings was accompanied by a series of spoken word recordings. For lockdown one, these were an announcement of the days—day one, day two etc.—providing a sonic punctuation to the shifting days of the first lockdown. For lockdowns two and three, I recorded my reading the days poems. The scrolls, fully unrolled and laid on the floor, led away from their associated speaker; the scripta continua were placed in the remaining floor space.12 Given their length (up to 17 metres), the scripta continua crossed the scrolls and each other. Thus, all the floor placed text works had to be walked around/over/along to read them.

Walking Contención Island scrolls

Across three sets of walks of 42, 28 and 83 days—153 days in total—Walking Contención Island represented my single longest act of composition and daily writing, and I presented this across three scrolls.

The first scroll, from The 42 walks of Contención Island, sets out an artistic and socio-political context for the work and the emergence of the island. The orientation of the scroll is clear with an obvious and constant top and bottom, and in this sense the scroll shapes the reading experience. As the line-drawing below the text charts the steady emergence of the island, orientation and time are defined through the reading of the scroll. It is formatted in a manner that allows reading at a table with two to three days on view at any one time, depending on how you position and imagine the days in front of you. When the scroll is placed on the floor and fully extended it is possible to see all 42 days, though to read any one day requires an act of focus. While concertina-fold books had been designed to be a more private, hand-held, reading experience (Micchelli, 2014; Scheier-Dolberg, 2015), the scroll needs about one and a half metres of space at a table of some height, and it also needs to be actively handled—wound out and in with respective hands as the reader moves along the scroll; this rolling and unrolling of the scroll needs a degree of physical coordination and management as a reader moves along the walks.13 This is reading as an active, coordinated, physical task and, in this sense, could be considered analogous to walking.

The set of poems in the first scroll charted the evolving daily political events and the structure of the mesostic was able to present more detail of the daily walks than I had typically presented in haibun. My mesostics covered three subjects. I chose a news headline-type topic for each day and the vertical word(s), emerging from text describing my walk, were my response to this. For example, on Sunday 3rd May the headline is ‘An NHS doctor writes of government “lauding heroes” whilst watching them die without PPE’ and the vertical text, from 11 lines describing my walk is ‘HOWDARETHEY’. In formatting the vertical text, when there was more than one word, as there frequently was, I chose not to separate them, so they were presented as a column of continuous letters, like a small vertical version of a scripta continua. Brunton (2018, p. 70) argues that the mesostic form is political in that it creates what Ranciere calls a ‘dissensus’, ‘a conflict between a sensory presentation and a way of making sense of it’ (Ranciere, 2010, p. 139). The eye naturally falls on the traditionally orientated, easy to read, horizontal lines that offer a direct account of my daily walk (in the style of Mark Goodwin’s Cornish walk or Sean Borrowdale’s Notes for an Atlas). Out of these accounts my harder to decipher, vertical words emerge—my response to the political actions of the government of the day.

The second scroll, from A walk round Contención Island, shares the presentation and reading experience of the first, but with the second scroll there is a shift in emphasis from the poetic style of the first scroll with its use of the mesostic and socio-political commentary, to the use of haiku and a greater reliance on symbolic resonance. I make frequent mention of the natural world, particularly birds, a reflection of my own interests and perhaps a reflection of the fact that walks were often made relatively early in the day when anthropogenic sound was reduced, and birds more active. Reminiscent of the first scroll, the drawn island (re-)emerges, day by day, towards its completion over the 28 days.

The third scroll, from Walking to the Sounds of Contención Island, differs from the first two in that the text is formatted such that it doesn't assume the same, constant, reader position. The images are intentionally layered and complex, offering a dream-like presentation of the island. The original images, from which the composite is formed, had four directions relative to the island (up, down, in, out) but for the reader/viewer there are only three. Whilst the composite image shows a constant directionality of up (sky at the top) and down (grass at the bottom) their only other dimension is along, born of the method of presentation. My additional dimensions of in/out are lost. Although it has an underlying syllabic haiku structure, the text is presented as a single line per haiku. There are generally one or two per day, occasionally three. These are presented in any and all orientations over the images of the days from which they came. This presentation of the text no longer assumes a seated reader and was designed to be viewed/read laid out fully extended on the floor. With the first two scrolls I suggested the required co-ordinated physical act of handling the scroll was analogous to walking. Here, with the scroll having to be moved along, over and across, the required co-ordinated physical act is walking.14

In my daily walks I was exploring places I had never been despite living in the area for 40 years—back alleys, cut throughs and cemeteries. I was also exploring different ways of walking—walking as an act of avoidance, avoiding passing close to other pedestrians, stepping off pavements, passing by on the other side of the street, all in order to stay within the rules of containment. Whilst walking I was also listening to my locale, something that I routinely do wherever I walk. Much of this listening felt like a familiar act of urban listening and I did not experience the widely commented lockdown quieting—the sounds of even a small amount of traffic created a background hum (or roar, depending on the distance). It was only on the early morning dawn walks that mechanical noise was scarce, leaving birdsong uncontested. Generally, my recordings still collected what Hosakawa described as the ‘kind of tone a city has, that the inhabitants (are obliged to) hear’ and Kimmelman described as ‘sound ... the “unspoken plague” of modern cities due to its persistent neglect’ (in (Ouzounian, 2020, p. 152)).15 Considering the idea of a city being experienced as an acoustic whole Ouzounian asserts that the city is too large and describes Peter Cusack’s suggestion that these sounds are compartmentalized as ‘a series of distinct “sonic places” that are seamlessly stitched together to make an irreducible, always evolving assemblage’ (Ouzounian, 2020, p. 158). This would certainly fit with Walking Contención Island where the mix of sonic places was shaped by the mix of places through which I walked. That said, these differing places were all stitched together by the needle of vehicular traffic and the thread of roads. For me, there is a dimension of all large urban conurbations that feels antipathetic to the presence and pace of a human walker—‘The processes of furious acceleration, accumulation, and rapid movement that shape such places conjure a city not as a dwelling place for bodies, but as a technology into which bodies are input and through which they are processed, often in violent and destructive ways’ (Ouzounian, 2020, p. 154).

On to 5.6 Reflections on A Pattern of Islands

Back to Table of Contents