4.2.2 One Day in June

In early 2016 (prior to starting this PhD) I produced an eight-channel 70 min. sound installation, Daag Einn I Juni, based on recordings of a replicated walk in Iceland.1 Having composed Orford Replication, I was curious to use these recordings to further explore such presentations of a replicated walk and composed a work for radio, and based on that radio work, a further installation.

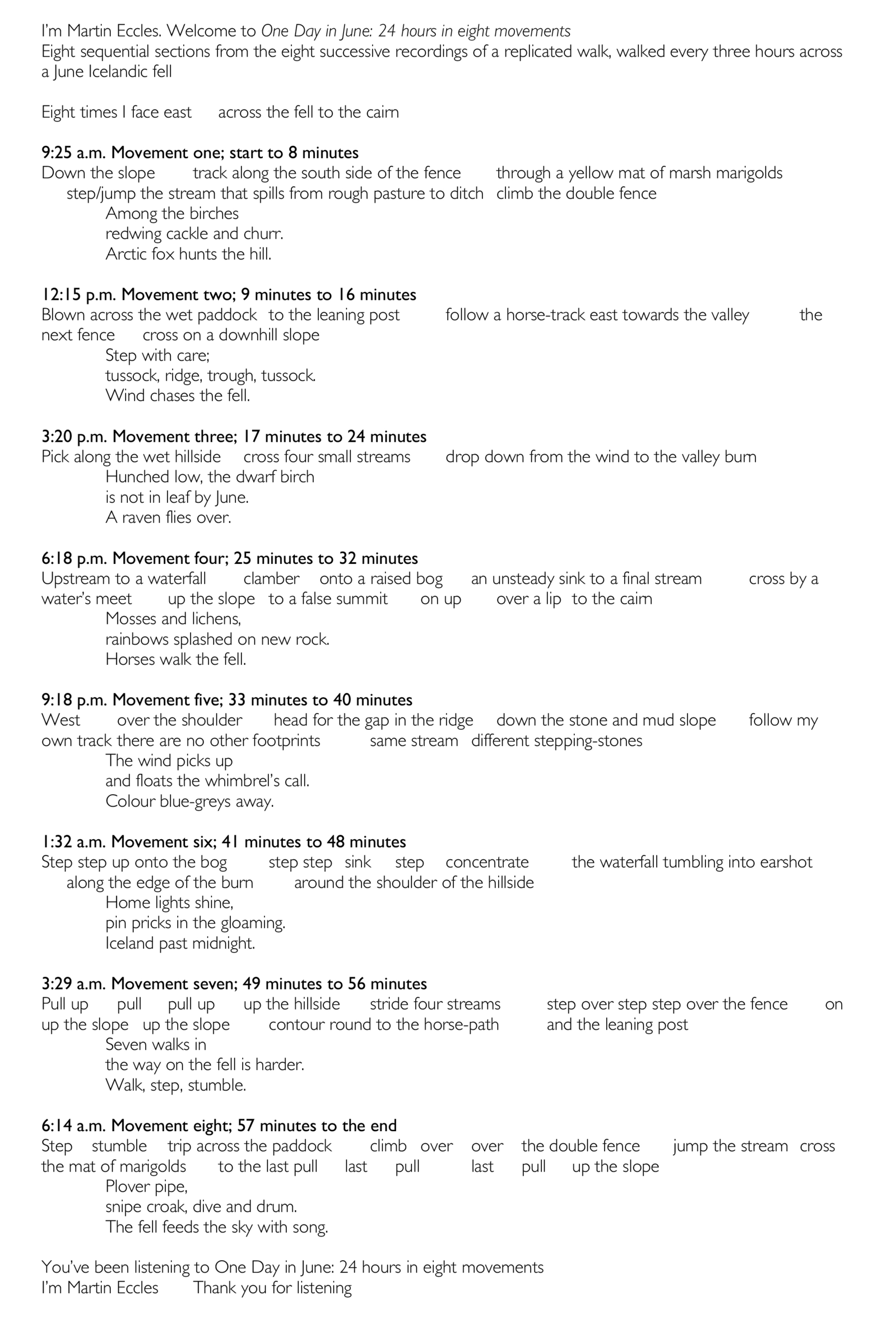

One Day in June: 24 hours in eight movements (a work for radio)

I had recorded myself walking the same route across an Icelandic fellside eight times, once every three hours, for 24 hours. With, once again, a broadcaster-prescribed length of 57 min. and a walk length of about 60 min. I again used the composition principles of my method from Orford Replication. Again, the process was adjusted to allow for slightly different lengths of each track and the need for a sonic as well as a temporal progression.2 Alongside the field recordings I wrote and recorded eight haibun based on my original notes and the sound content of the recordings. For this composition I added them to the start of their corresponding walk section. The script (radio intro and outro and the eight haibun) is shown below.

One Day in June (a two-channel installation)

Interested in continuing my exploration of ways of presenting sound and text within the same physical space, I took advantage of an opportunity to install this stereo, radio, version of One Day in June in a gallery space (below).

I used the same replicated walk material as for the radio production.3 I sent the field recordings to one speaker and the spoken haibun to the other.4 I added a booklet containing the written haibun (as above) and a ‘text line’, a scripta continua (Maitland, 2009, p. 147).5 This was the haibun presented as a single line of unspaced, unpunctuated lower case text; about 620 cm long. The scripta continua was placed across the floor between the speakers thereby, in addition to its content, working as an object within the installation space.

Placing text works on the floor removes the constraints of a support and allows them to have a physical presence of their own within a gallery space; they have a top and a bottom, a right way and an upside-down way to be read. In my use of them their length can be considerable; here the scripta continua effectively divided the gallery space in two (as did a subsequent one in Walking Contención Island). This added a further dimension of interaction for a reader; it invited being stepped over in the way that I stepped over streams in the field recordings. Thus, readers were free (almost obliged) to move across and over, back and forth along the strip, back and forth along the text, and forward and back in time, this in a manner comparable with the act of moving between the speakers of a sound installation. The strip is a metonym for the walk.

When reading the scripta continua, it is not straight forward to make sense of the content. As with the text and haiku presented as booklet or folded sheet, the letters reflect the sequence of my walking. However, to read the strip a reader must do two things. As with all of my longitudinally formatted text works, they have to move, back and forth along it, to walk, to physically be near the text. In addition, they have the added task of rebuilding my words out of the unbroken text, or of building their own, new, words from within the letters. Rebecca Solnit wished that her ‘sentences could be written out as a single line running into the distance so that it would be clear that a sentence is likewise a road and reading is travelling’ (Solnit, 2002, p. 72). Discussing this wish and the idea of storylines, Ingold suggests that a fundamental problem with this is that text consists of sentences governed by the rules of grammar and that constituent words don’t occur along a path, as they do for an oral storyteller, but exist as discrete entities laid out on a page. Therefore, ‘Solnit’s line, which has the appearance of a string of letters interrupted at intervals by spaces and punctuation marks … is not a movement along a path but an immobile chain of connectors.’ (Ingold, 2007b, pp. 90-96). My scripta continua, as continuous flows of letters, are not constrained by such grammatical connectors but allows the reader to make their own way through, to tell their own story, making their own words as they do so. Without fixed, immobile connectors they encourage a continuum of reading, an ebb and flow, back and forth in the place of reading, and back and forth in a reader’s imagination.

4.2.3 Búðahraun

This was the second of the re-visited works.6 The work was recorded on the western Icelandic lava field of Búðahraun. Arriving mid-evening on the summer solstice I recorded a 15-minute walk into the lava field, stopped and left the recorder running for about 40 minutes, and then recorded the walk back to where I had started. I returned early the next morning and repeated the walk—a replication across the solstice.

Utilizing the same idea as Orford Replication I composed a two-hour stereo work for radio. To accompany this, I wrote a haibun (Figure 4.7); my recorded reading of this was incorporated into the beginning of the broadcast.

The overall structure of the radio piece deliberately moved backward and forward in time mixing the sequencing of walking and static recordings.7

4.2.4 ‘trace no trace’

The details of ‘trace no trace’ have already been described in section 3.2 where they are presented and discussed as works that highlight the embodied, sensate dimensions of my walking. However, the constituent walks also contain replications and are therefore also included in this group of works. No. 1: ‘trace’ involved a route being walked once underground and then repeated as a route across a fellside. No 2: ‘no trace’ involves the same route in a river walked once around the winter solstice and again on the spring equinox.

On to 4.2.5 begin to hear

Back to Table of Contents