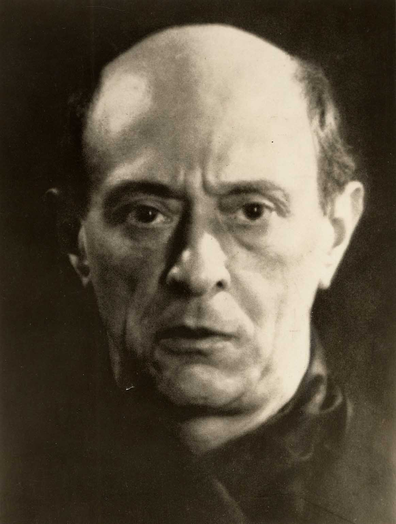

At the same time that all of these new ideas took shape in his mind, Cage began his composition studies with Arnold Schoenberg [4]. In these lessons, he discovered his “inability to work with traditional pitched material, therefore he had to be interested in the possibilities offered by non-pitched music” 3 (Nicholls, 2007, p. 38). Despite this fact, he wrote some pieces using his teacher's twelve-tone system during those years. In this compositions, Cage tried to mask the row, instead of emphasizing it as the fundamental support of the compositional system. On the other hand, he learnt from Schöenberg that a musical structure is the result of dividing a piece into sections. However, Cage did not agree that harmony determinates this division. For Cage, time was the capable element of structuring a piece. Time is the most fundamental category. It exists before pitch and harmony and contains both musical sound as noise and silence. In those years, Cage associated time with the number of measures of the piece, all of them with the same duration.

Shortly after giving up lessons with Schoenberg, Cage began to structure music according to time instead of pitch. He focused on rhythmic structures: pre-composed temporary structures on which music must fit in a posteriori. The most outstanding structure is called "square root formula" and its guiding principle is: the same proportion will determinate the musical phrase´s division (microstructure) and the piece´s general structure (macrostructure). “Through the use of percussion instruments which had no access to pitch, but which allowed me to give a structure to the compositions” (Ford, 2001, p. 176). Therefore, Cage´s aesthetic is surely more influenced by Cowell than by Schoenberg. From Schoenberg he acquired only the compositional discipline and a need for musical structures.

In 1937, Cage got a position at the elementary school of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). He worked as accompanist, percussion teacher and collaborated with dancers as performer and composer. These activities brought him towards the development of the rhythmic structures aforementioned, essentials in working with dancers, or the invention of a new instrument: the water gong. The water gong origin is due to a commission of an aquatic ballet by the UCLA swimming team. The swimmers could not hear the music when they were submerged, but Cage discovered that if he sunk a gong after beating it, they could heart it and were consequently able to adjust better to the music. The main characteristic of this instrument is that the gong´s frecuency lowers when it is partially submerged in a liquid, that is to say, it does a descending glissando when we submerge it and ascending glissando when we raise it.

That year, Xenia Cage, his wife, began as bookmaker apprentice with Hazel Dreis. Dreis forced all her apprentices to move to her mansion in Santa Monica. Cage took advantage of this situation by asking the other apprentices, together with his wife and himself, for a part of their free time to form a percussion ensemble [5]. They played music that Cage composed using kitchen utensils, binding material, junk, etc. Although members of this ensemble were not professional musicians, they rehearsed everyday acquiring a high level of performance. This fact, along with his marriages economic hardship, prevented him from buying instruments, and are the conceptual basis of works such as Living Room Music (1940) or First Contruction (in Metal) (1939).

In the summer of 1938, Cage and his wife moved to Seattle, where one year earlier, Cage had given his famous lecture "The Future of Music: Credo". This conference, organized by B. Bird in an artistic society, was vital for the upcoming development of contemporary music. In this second time, Cage found a stable position at the Cornish School through composer Lou Harrison, with whom he shared ideas about composing for percussion and dance. During his stay at the Cornish School, Cage accompanied the dancer Bonnie Bird, composed new music for specific performances and continued developing his percussion ensemble. In that situation, First Construction (in Metal) was premiered on December 9th 1939.

At the beginning of the 1940s, Cage was constantly looking for new sounds: exotic instruments (cowbells, oxen bells, teponaztli, quijadas, etc.) and found objects (tin cans, brake drums, conch shells, etc.). This resulted with them being added to the conventional percussion instruments (bells, cymbals, tam-tams, etc.). However, the most important innovation was the prepared piano.

1.1. John Cage and his early percussion music

John Cage (1912-Los Angeles, 1992-New York) [1] is one of the most influential composers of the XX century, not just because of his musical innovations but also because of his role as a philosopher, painter and writer. Cage is mainly known for his contributions to electronic and chance music, as well as for the use of unconventional instruments. Although these are the fundamental pillars of his fame, the focus of this research will be on his first stage as a composer, when he had not looked into the possibilities of chance yet.

Cage´s first compositions were short pieces for piano written through complex mathematical procedures. His next step was to compose through improvisation. In 1931, after a trip to Europe, Cage began to study composition with Richard Buhlig in the New School for Social Research (New York). At this time, Cage learnt about non-western music, folk and contemporary music. “Buhlig advised him to stop composing through improvisation and Cage began to develop compositional techniques based on Schoenberg’s twelve-tone system” (Bernstein, 2002, p. 63). During the first half of the 1930's, Cage developed a complex serial system based on a twenty-five-tone row. Although this technique was used in some pieces, e.g. Six Short Inventions on the Subjects of the Solo (1934) or Composition for Three Voices (1934), he gave it up soon.

The invention of the prepared piano is directly related to Bird: Cage had to compose a new piece for Bird's outstanding pupil, Syvilla Fort [6]. "Three or four days before she was to perform her Bacchanale, Syvilla asked me to write music for it. I agreed" (John Cage's foreword in Bunger, 1981). The piece would be suitable for a dance suggestive of Africa. "The Cornish Theatre in which Syvilla Fort was to perform had no space in the wings. There was also no pit. There was, however, a piano at one side in front of the stage. I couldn’t use percussion instruments for Syvilla’s dance, though, suggesting Africa, they would have been suitable; they would have left too little room for her to perform. I was obliged to write a piano piece" (John Cage's foreword in Bunger, 1981). Cage first tried to find an African twelve-tone row, but he did not succeed. His next attempt was to modify the piano. After trying different objets (such as pie plate and nails), he found out that screw or bolts were the most suitable preparations. Cage also realised that it was possible to get two sounds out of the same preparation, one resonant and the other, quiet and muted by pressing the soft pedal.

In the light of the above, it seems that Cage created both a new instrument and piece in four days. However, as Luk Vaes explains, the emergence of the prepared piano was a longer procedure: "In actual fact the invention of the prepared piano came at an intersection of several roads that had been converging for a while until they connected with Cage for this historical event" (Vaes, 2009, p. 695). It has already been mentioned how Varésé's Ionisation (1931) influenced Cage. This is one of the first pieces for percussion ensemble and it includes a part for piano and percussion instruments. "Percussionists were asked to play keyboard instruments or pianists were asked to perform on a few percussion instruments next to their keyboard" (Vaes, 2009, p. 682). In 1933, William Russel composed Fugue for eight percussion instruments, a piece that also includes piano in its instrumentation. Russel went much further in the use of extended piano techniques than Varése had done: scratching strings with a coin, striking the strings with rubber ball mallets, etc. However, as mentioned above, one of the most important influences in Cage´s early music comes from H. Cowell, not simply for sharing similar aesthetics but also for the use of string piano.

There are examples of him using string piano in his early compositions [7]. First Construction (1939) contains a string piano part with an assistant. In this piece, the assistant applies a metal rod on the strings producing a glissando of overtones among other effects. One year later, Second Construction (1940) also has a part for string piano. In Second Construction the techniques are significantly different: gong beater sweeping the strings, playing while muting the string with two fingers of the left hand, insertion of a cardboard between strings in the treble clef or placing a screw between two strings. Therefore, it is obvious that Cage composed for piano with preparations before Bacchanale. However, “although, the prepared piano made its first appearance in the Second Construction, Cage attributed its origins to Bacchanale (1940)” (Bernstein, 2002, p. 77). By any definition, the piano in Second Construction has been prepared (cardboard inserted in between strings), then it should be an explanation to justify the previous quote. Vaes proposes two hypothesis for this question: Cage could consider that prepared piano only has fixed preparations. In this case, Second Construction, that employs both fixed and mobile preparations, would have been composed for string piano but not for prepared piano in contrast to Bacchanale, in which all the preparations are fixed. The second hypothesis is much more simple: "Cage always (wrongly) remembered having composed Bacchanale in 1938, and Second Construction in 1940" (Vaes, 2009, p.711)

At this point, it is necessary to clarify some terminology: the differences between the string and the prepared piano are not always clear in Cowell's and Cage´s works. Cowell never used the term "prepared piano". Therefore, in his case, any grand piano with fixed preparations or mobile modifications is a string piano. However, Cage used Cowell´s string piano as a reference and later he developed the fixed preparations. Because of this, he utilizes both terms and sometimes it can be confusing to distinguish between the two instruments.

To complete this chapter, it is important to have a precise definition of what a prepared piano is. The earliest definition for it is found in the score of John Cage's The Perilous night (1943-1944): "Mutes of various materials are placed (in a grand piano) between the strings of the keys used, thus affecting transformations of the piano sounds with respect to all their characteristics".

The work of Oskar Fischinger [3] and Edgard Varése (Ionisation [1929-1931] for percussion ensemble in particular) reaffirmed the influences that Cowell had on Cage. Ionisation is one of the first works composed only for percussion and it has an extremely innovative instrumental template for the time: factory sirens, maracas, lion´s roar, etc. In those years, these elements were bound to draw the attention of the musical community. In 1935, Cage traveled to Los Angeles to study with Schoenberg and, in that trip, he met the film producer Oscar Fischinger. The following quote summarizes Fischinger´s contribution to a conversation between him and Cage: “There is a spirit inside each of the objects of the world, all we need to do to liberate that spirit is to brush past the object and to draw forth its sound” 1 (quoted in Nicholls, 2007, p. 38).

In this way, Cage was open to compose using not only percussion instruments and noise generators (such as lion´s roar or sirens) but also any other everyday object. Perhaps this interest inspired Quartet (1935): “It is even possible that Quartet is, in fact, the soundtrack of a Fischinger´s film” 2 (Nicholls, 2007, p. 38)

Cage was 21 years old when he met the composer Henry Cowell [2] during a visit to New York. Cowell, who was highly involved in percussion music composition, did not teach Cage (he suggested to Cage to study with Schoenberg), but Cowel did have a special influence in the aesthetics of his compositions. One of the most relevant ideas Cage learnt from Cowell is found in the following quote: “The music was meant to flow along regularly, while you did irregular things” (Quoted in Miller, 2002, p. 153). Cowell had been working with dancers for several years and he concluded that contemporary dancers were always performing a pre-composed music. Their work was constantly subordinated to the music they had to choreograph. After writing some articles about this problem, he found the solution splitting the rhythm of dance from the rhythm of music. Later, Cage applied this solution in his own pieces (e.g. Double Music [1941] in which Cage writes two of the quartet´s parts and Lou Harrison the other two), as well as his assiduous collaborations with Merce Cunningham (both artists worked separately, based on a common rhythmic structure, but neither of them knew the music of the other until the premiere).

Apart from this new approach to music-dance relationship, Cage and Cowell shared the same ideology about which sound could be used to perform music. “Any sound is acceptable to the composer of percussion music; he explores the academically forbidden ‘non-musical’ field of sound insofar as is manually possible” (quoted in Nicholls, 2002, p. 16). Musical instruments are not the only source of sound anymore. They deleted any prejudice when choosing sounds for a composition. Therefore, any object capable of producing sound can be treated as a musical instrument.