Act 5: Two proposals for a historically informed approach to Mercadante’s flute works

At this point of my research, and given the premises I explained in the intermezzo, I was forced to re-imagine my approach to Mercadante’s flute works. A mechanical copy-paste of information I could have found in a source was not possible anymore. I was looking at an extraordinary amount of highly virtuosic compositions while having a limited amount of time to sufficiently assimilate and experiment with them.

My first decision was then to focus only on Mercadante’s two most popular pieces: the variations on “Là ci darem la mano”1 and the Rondò russo from the flute quartet2 (and concerto)3 in E minor. In this way, I thought, I could try to “debunk” some standardised performance practice elements and try to shed a new light on them.

However, the bias jungle in which I found myself while practicing was way too dark to be able to see something. I had been listening to recordings of those pieces for all my teenage years and the impression of such standard practices was still very strong in my imagination. I could not conceive them in a different way than with rallentando at every cadence and vibrato even on 16th notes. My canvas was not white enough to create a new picture: I could only colour the existing drawing.

I felt that I would not have managed to reach the other side of the jungle without the proper tools given to me by some sources. I therefore decided to create a detour and to work on two pieces that shared several characteristics with the above-mentioned ones but were also different enough to allow me to create my own interpretation from scratch.

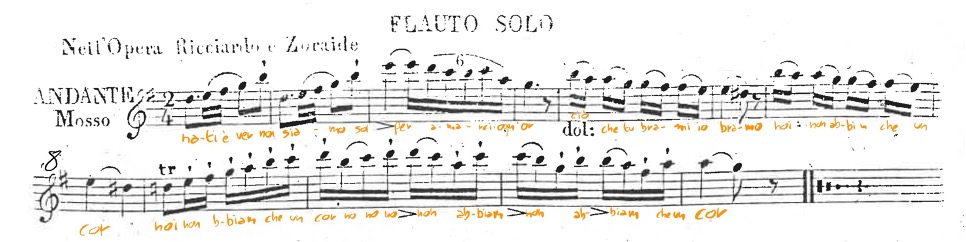

Instead of the variations on “Là ci darem la mano”, I chose the ones on “Ah nati è ver noi siamo”4, which set itself apart from the others for its refined writing and expressive possibilities, while sharing some variation elements with my original choice.5

Instead of the Rondò russo, I chose the final movement (Rondò, Allegro brillante) from the flute duet op. 156 n. 2,6 which formal structure and thematic punctuated rhythm immediately reminded me of Mercadante’s most popular piece, although with a completely different instrumentation.

Satisfied with my choice, I decided on the conditions for my two experiments:

-

My colleague and I would have played a modern copy of an 8-keyed flute after Grenser, which is the only instrument that we own that we could use for a performance of early 19th-century music. However, given its high flexibility, I decided to treat it as a 4-keyed French-style flute, as this still seemed to me the favourite model for flute players of the time when considering the surviving instruments.7 As a consequence, I did not use the high C and the long F keys.8 Moreover, I used fingerings that typically work on French instruments and are presented in French methods, such as the C2 as OXX/OOO/o,9 instead of the German long fingering OXO/XXX/o.

-

Nevertheless, I also knew that I should have not been too French. For this reason, I decided I would avoid the fingerings for the notes sensibles that raise the pitch of leading notes since they were so characteristic of French flute players.10

-

Finally, I would have trusted my taste while making artistic choices, but I would have also looked for some further inspiration in Pustlauk’s dissertation.

Scene 1: Varied aria Nell’Opera Ricciardo e Zoraide

Firstly, I decided to get acquainted with the opera Ricciardo e Zoraide by Giacchino Rossini, nowadays almost completely unknown. Interestingly, it premiered at the Teatro San Carlo in Naples on December 3rd, 1818,11 and was therefore probably still quite fresh in the memory of the audience when Mercadante published his third collection of variations a few months later.

Ricciardo e Zoraide is the story of Ricciardo, a Christian knight trying to rescue his lover Zoraide, Asiatic princess captured by the tyrant Agorante. At the beginning of Act 2, the two lovers are finally able to meet again and confirm their feelings to each other:

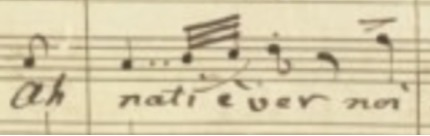

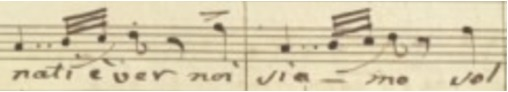

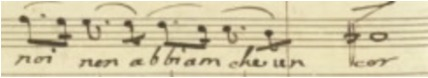

| Ah, nati è ver noi siamo

Sol per amarci ogn’or. Ciò che tu brami, io bramo, Noi non abbiam che un cor. |

Ah, it is true that we are born Only to always love each other. What you desire is what I desire, We only have one heart. |

My first step was then to place the text in Mercadante’s arrangement, using the original manuscript score kept in the conservatory library in Naples as a guide.12

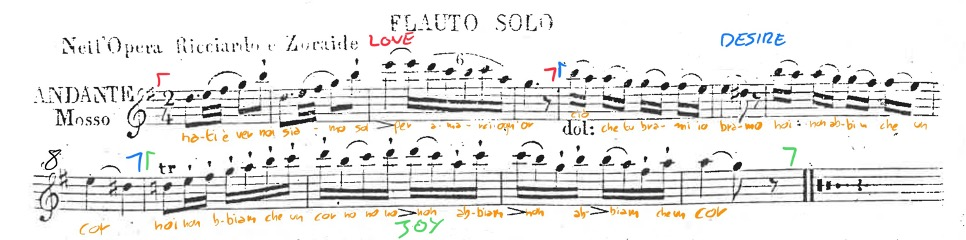

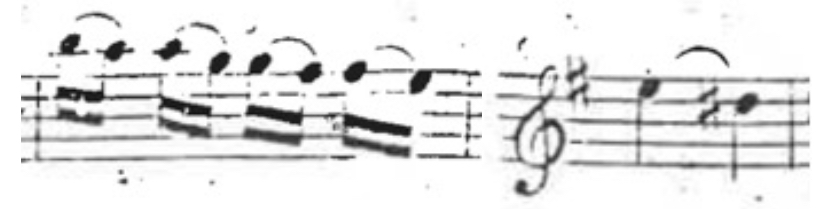

The text placement highlighted the different affects of the short 12-bars melody. The first four bars could represent “love”, culminating with the sweet ornamentation on “amarci”. In the following four, the minor section and the paired slurs could switch the atmosphere to “desire”, and in fact the verb “bramare” is repeated twice. Finally, the recognition of mutual love, the dots and the high register seemed to me a representation of joy. In the first performance of the theme, I then kept in mind such distinctions:

-

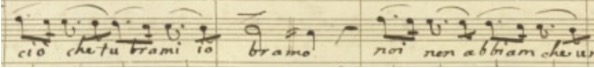

The dotted rhythm in bars 5, 7, and 9. Since the opera was performed for the first time only a few months before the publication of the varied aria, I would assume that flute players had in mind how the original sounded. However, I tried both to keep the equal rhythm and to add some inégalité. In the end, I decided to keep a dotted rhythm since it better expresses the sense of desire and, later, joy in the text.

Right at the beginning of this variation, I had to decide whether I wanted to play a strong metrical accent13 and to respect the hierarchy of the bar

Despite the idea that Neapolitan flute players played in a “virile” way (whatever that means), I find the first solution too mechanical. At least in this specific context, I would consider them as oratorical accents.

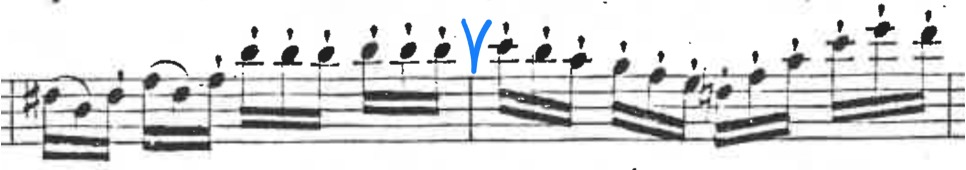

The last problem that I encountered in practicing this variation concerned the transition between bars 8 and 9, where the change of affect from “desire” to “joy” happened.

The second solution seemed to me the most natural. However, what does “natural” mean? Personally, I tend to consider it a synonym of “conventional”, of what I am used to hear and play, and therefore to challenge my choices every time this word pops in my head. Does this slight rallentando actually reflect the taste in Naples in the 1810s? Unfortunately, I have no available documentation as a devil’s advocate for the other choice. To deliver a convincing performance of it, however, I can only accept what feels better for me right now.

No such variety is explicitly written in other variations. In fact, it could simply be a typo,14 but a different articulation might have also been an artistic choice. I personally found it convincing and decided to keep it and to use it as an inspiration to introduce a small ornamentation in bar 8 as well to differentiate it from the identical bar 6.

Moreover, the sforzato on the high E flat suggested me the possibility to use a breath vibrato15 to highlight such a dramatic passage.

Since the first time I played the piece, I felt that the descending semitone between bar 8 and 9 would have been a perfect place for a glissando,16 both technically (through the simple sliding of the fingerings from OOO/OOO/o to OXX/OOO/o) and musically.

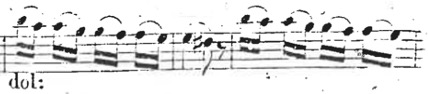

Due to the repeated fast connection with the C, I thought that using the standard B fingering XOO/OOO/o would have resulted in moving too may fingerings to keep the “dolce” character. I therefore used XOO/XXX/o, which not only allowed an easier connection between C and B at the beginning of bar 5, but also raised the pitch of the Bs in bar 6, which I could then play with more grace.

Scene 2: Rondò from Duetto op. 156 n. 2

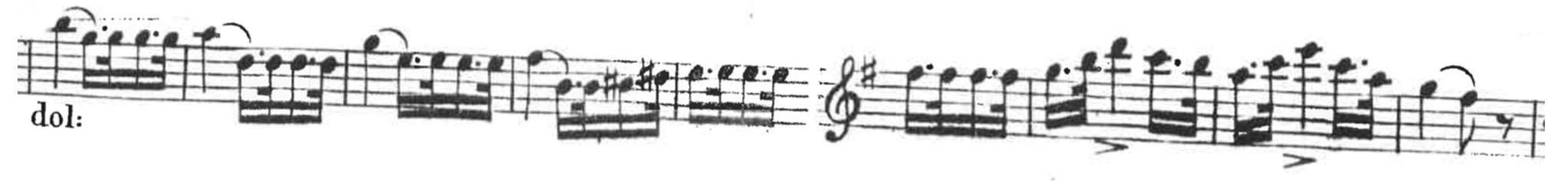

Unlike the variation sets, no extra-musical material is available for the duets. All the historical information I had is that the Duetti op. 156 were published in Naples in 1818. I could only rely on the musical text and, partially, on my previous experiment with the variations.

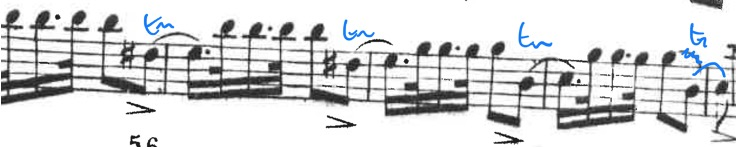

As the first flute, in the first bar I decided to respect the hierarchy of the bar instead of following the ascending melody, as I did for the previous piece. The goal is to mark the appoggiatura (and, therefore, the dissonance) that the C creates at the beginning of bar 2.

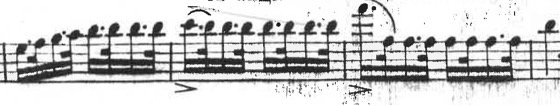

As a general rule to integrate slurs in the eight notes accompaniment, I decided to keep four notes slurred together only in the case when all of them where ascending or descending, as in bar 2; when the regular movement of such notes was broken, I slurred the notes in pairs. This seemed to me to be the most effective way to imitate the left hand of a keyboard player.

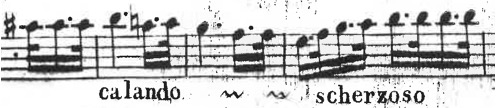

In order to achieve a better contrast between the “scherzando” main theme and the “dolce” secondary one, we played the latter slightly slower and less articulated. However, the following syncopations seemed to already express a new idea, less “dolce” and more “scherzando”, so to say. For this reason, we accelerated a bit towards them and then relaxed again on the final appoggiatura.

In the coda, the same material is repeated by the two flutes without any explicit variation. Therefore, I decided to be consistent with my previous choices and to introduce again a little variety. The perfect spot seemed to me the second C of the phrase, since it is by itself a repetition of musical material inside the four-bar half phrase.

[To Epilogue]