Making places for children’s studios.

Marike Hoekstra

Introduction

Gastatelier de Vindplaats is an informal shared art studio in a school building in Amsterdam. Children can join - free of charge - in their own neighbourhood, there is room for everybody to be engaged on their own terms as often as they like, and most of the materials used consist of recycled goods. Gastatelier aims at participatory practice because of the way it engages with school routines, family relations and neighbourhood activities. Additionally but distinctively, it is an artistic residency where artists are allowed time and space to “work, individually or collectively, on areas of their practice that reward heightened reflection or focus” (European Union, 2016). Finally, Gastatelier de Vindplaats is also a site for development and research. Pioneering in this unknown territory brings about many questions of varying natures. In this exposition I want to discuss some of these key questions concerning the notions of space and place.

When doing research, investigating practices in depth and at length in the tradition of ethnography in order to find interpretations of complex lived realities, the results we find may not always come from the questions we initially asked ourselves. The research process often starts from a focus point which emanates from the gaze of the researcher. Even though the research might not be aimed at finding evidence for a hypothesis but is instead rather qualitatively oriented around open ended themes or points of interest, the fact that a researcher tries to take this open holistic approach might result in what is often referred to as serendipity. Serendipity is the phenomenon of unintended findings (Kennedy, Whitehead & Ferdinand-James, 2022). One of the unintended findings of my own research project into artist-teachers and democratic pedagogy was my growing awareness of the relevance of place and space in order to understand pedagogical realities. My own research findings illuminated the fact for me, as an artist-educator-researcher, that thinking about pedagogical practices always involves a spatial perspective and that space is never neutral. Since investigating pedagogical spaces was not my intention when I started my research, I registered the findings as incidental discoveries. I addressed the spatial aspects briefly in my thesis (Hoekstra, 2018), knowing that I had unintentionally discovered a path I had not yet walked, but that might lead me to wonderful new territories if I were able to take up researching again.

The workshop I developed for the symposium Artistic Connective Practices called Making Places for Children’s Studios is a result of my desire to find arts based participatory methodologies to investigate the spatiality of radical arts pedagogical practices and of recent developments in my own practice as an artist-educator-researcher. In this text I want firstly to introduce how my current socially engaged practice with a school community came to be and secondly explain how a participatory art based intervention I developed some years ago during a Tate Exchange project became the inspiration for the workshop. Lastly, I will conclude by elaborating on a more recent event in my practice and underpin this experience by referring to the inspirational alternatives proposed by Falk Hübner in his inaugural lecture (2022) and propose a way to take my research further in correspondence with some of the themes identified in the lecture.

References

Adams, J., & Owens, A. (2016). Creativity and democracy in education. London, United Kingdom: Routledge.

documenta fifteen Handbook (2022). Berlin: Hatje Cantz Verlag.

European Union (2014) Policy handbook on Artists’ Residencies. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/assets/eac/culture/policy/cultural-creative-industries/documents/execsumm_residencies_en.pdf

Fraser, T. A. (2016) The Nature of the Studio: An Artist's Method of Inquiry. (Doctoral dissertation, University of Melbourne). Retrieved from: https://minerva-access.unimelb.edu.au/handle/11343/113589

Giroux, H. (2021). Education, politics, and the crisis of Democracy in the age of pandemics. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 21(4), 5-10.

Helguera, P. (2011) Education for Socially Engaged Art. A Materials and Techniques Handbook. New York: Jorge Pinto Books.

Hickey-Moody, A., Horn, C., Willcox, M., Florence, E. (2021). Introduction. In: Arts-Based Methods for Research with Children. (pp. 1-15). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Hoekstra, M. (2018) Artist teachers and democratic pedagogy. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from: https://chesterrep.openrepository.com/handle/10034/621472

Hoekstra, M. (2019). A Place for Stupidity: Investigating Democratic Learning Spaces in the Diorama. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 38(3), 649-658.

hooks, b. (1989). Choosing the margin as a space of radical openness. Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media, (36), 15-23.

Hübner, F. (2022) In Good Company. Think we must. Inaugural lecture for the professorship Artistic Connective Practices. Tilburg: Fontys Hogeschool.

Illich, I. (1971). Deschooling Society. London: Calder & Boyars

Kennedy, I.G., Whitehead, D., Ferdinand-James, D. (2022) Serendipity: A way of stimulating researchers' creativity, Journal of Creativity, (32), 1, 100014

Kentridge, W. (2014) Six drawing lessons. The Charles Eliot Norton lectures, 2012. Cambridge/London, United Kingdom: Harvard University Press.

Kraftl, P. (2013). Geographies of alternative education. Bristol, United Kingdom: Policy Press.

Krauss, A. (2015a). …. To be hidden does not mean to be merely revealed Part 1: Artistic research on hidden curriculum. Medienimpulse.at. Retrieved from https://journals.univie.ac.at/index.php/mp/article/view/mi888/1019

Masschelein, J., & Simons, M. (2013). Het atelier als autonome pedagogische plek [The studio as an autonomous pedagogical place]. In M. Corsten, C. Niesten, P. Gielen, & H. Fens (Eds), Autonomie als waarde. Dilemma's in kunst en onderwijs, (49-71). Amsterdam: Valiz.

Moss, P. (2001). The otherness of Reggio. In L. Abbott & C. Nutbrown (Eds.), Experiences of Reggio Emilia: implications for pre-school provision (pp. 125-137). Buckingham; Philadelphia, PA: Open University Press.

Negt, O., & Kluge, A. (1990). Selections from "The Proletariat Public Sphere". Social Text, 8(3), 24.

Petrie, P. (2019) The Learning Framework for Artist Pedagogues. Blue Cabin. Retrieved from: https://wearebluecabin.com/latest/the-learning-framework-for-artist-pedagogues/

Ranciere, J. (2004). Who is the subject of the rights of man? The South Atlantic Quarterly, 103(2-3), 297-310.

Sagan, O. (2008). Playgrounds, studios and hiding places: emotional exchange in creative learning spaces. Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education, 6(3), 173- 186.

Sennett, R. (2017). The open city. In T. Haas & H. Westlund (Eds.), In The Post-Urban World (pp. 97-106). Routledge.

Soja, E. (1999). Thirdspace: Expanding the Scope of the Geographical Imagination. In D. Massey, Allen, J. & Sarre, P. (Eds.), Human Geography Today (pp. 260-278). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Blackwell.

Taylor, C. (2009) “Towards a geography of education.” Oxford review of Education: The disciplines of Education in the UK: Confronting the Crisis 35(5), pp 651-669.

Van Meerkerk, E. M. (2020). A Dictionary for the Collaboration between Schools and Arts Centers. Retrieved from: https://repository.ubn.ru.nl/bitstream/handle/2066/221019/221019.pdf?sequence=1

Vergeront, J. (2018) Children as Placemakers and Worldmakers. Museum Notes. Retrieved from: https://museumnotes.blogspot.com/2022/08/children-as-placemakers-and-worldmakers.html

Wilson, B. (2008). Research at the margins of schooling: Biographical inquiry and third-site pedagogy. International Journal of Education through Art, 4(2), 19-130.

The workshop: Making space for children’s studios

For the symposium Artistic Connective Practices hosted by Fontys Academy of the Arts, the last question raised in the call resonated most with my project and research proposal: in what way do artistic practice and research work to make socially engaged imaginary propositions? The proposition that Gastatelier de Vindplaats aims to make is to create a site for development and research in a continuous process of making and researching, slightly similar to what is called placemaking in urban development. Placemaking is a process that involves communities in reimagining and reinventing public spaces. It is a bottom-up, grass root approach to urban planning where the participation and imagination of the people involved is conditional. What I would like to find out is how the physical-spatial aspects of a studio can invite children to be placemakers of their own artist studio and how the natural qualities of children as placemakers (Vergeront, 2018) can play their part in the pioneering phases of a radical informal practice.

When working with concepts of space and place, an artistic methodology is an appropriate way to engage children as co-researchers, as I have experienced in previous projects. The research methodology for this project crosses boundaries of activism, ethnography, human geography and artistic research in order to make meaning out of a complex lived reality.

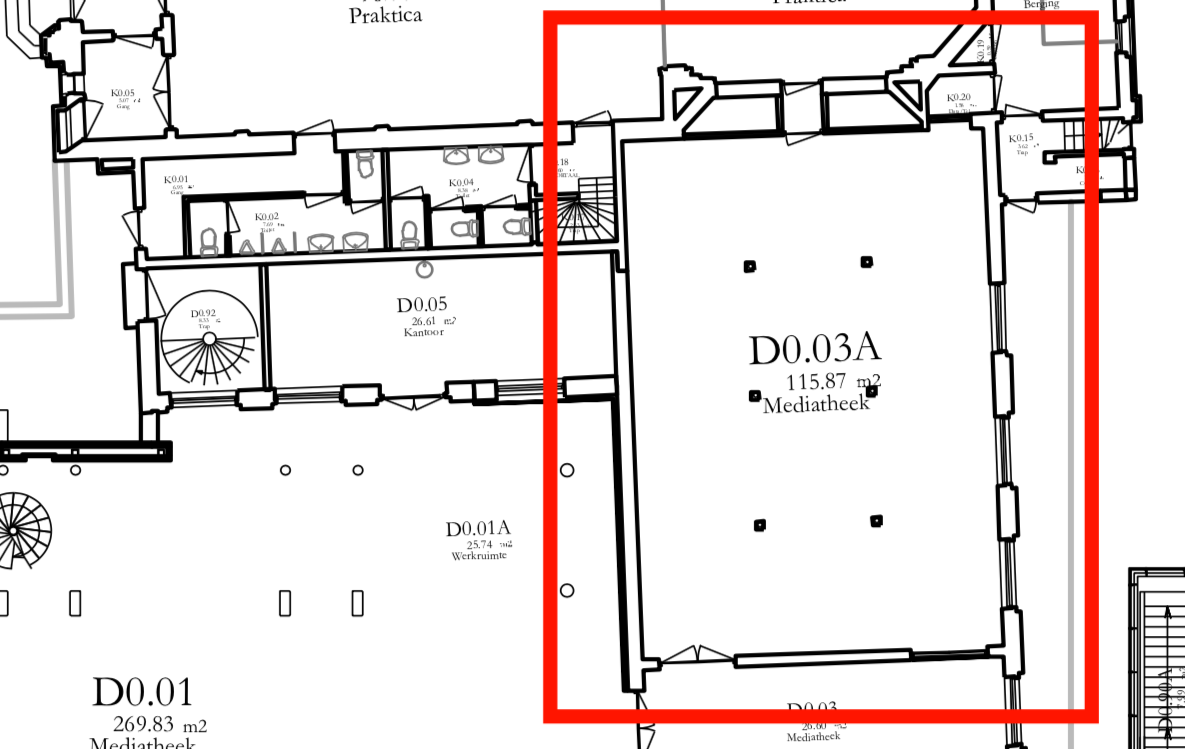

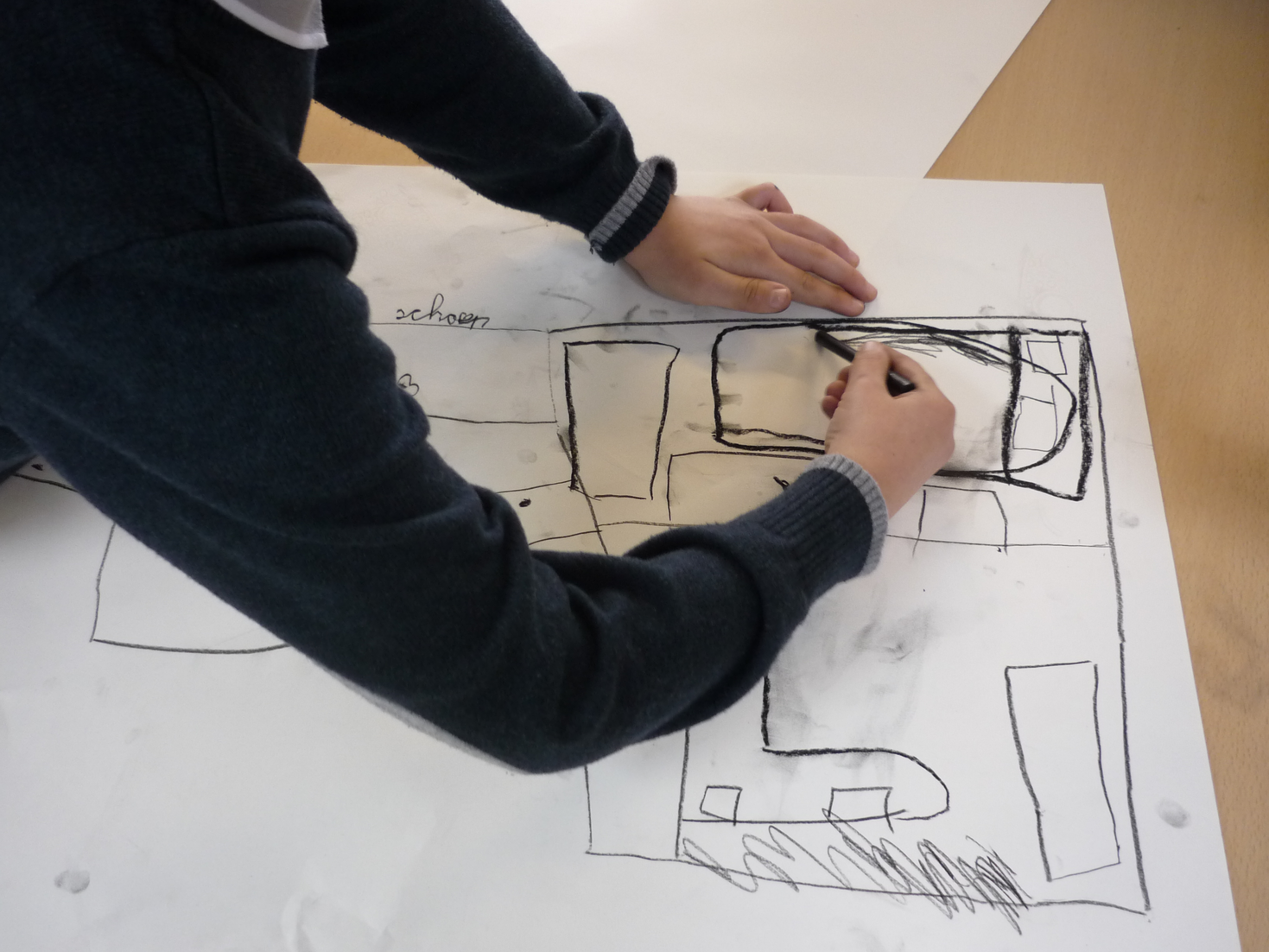

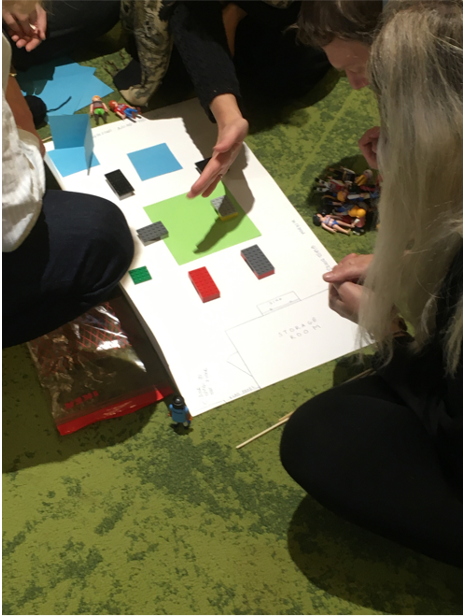

The workshop at the symposium centered around imagination: what would a democratic artistic studio space for children and artists look like when the participants were invited to play with the parameters of the studio? I provided sets consisting of a floorplan on a scale of 1:20 and 18 Playmobile-figures featuring the maximum number of children and adults working in Gastatelier simultaneously (with similar scaling) and put down a table full of creative materials borrowed from the studio. Participants scattered in small groups around the room to discuss and create miniature models of democratic studio spaces. Inviting an audience to think with me through making and playing engaged everybody in dialogue about the question of what makes a studio space democratic. What kind of space is required for children to feel included and experience agency? It struck me not only that I recognized my earlier experiences from the Tate Exchange in Tilburg, in how everybody engaged in playful making and arranging, but also that I could see that working in small groups, working from tables or on the floor helped the participants to express themselves, not just sharing ideas verbally but collaborating to visualize their dialogue, connecting everybody in the practice of imagination.

Observational fieldnotes on the floorplan of the Room13 studio space in Bristol. A distinguishing feature of the room is the wall which is placed right in the middle of the room, dividing the room in a way that allows to move around it, but more importantly, breaks with the expectation of complete surveillance in a classroom (Hoekstra, 2018)

Methodology; working with small scale diorama

In 2018 I was invited to participate in a Tate Exchange event in Liverpool around Arts-based Education Research: Mittens and Barbies (Hoekstra, 2019). During my doctoral research I had explored a methodology of creating miniature three dimensional models - or dioramas as I like to call them - to investigate the role of my own subjectivity as practitioner-researcher. Based on the experiences and outcomes of this art based methodology, I developed a participatory intervention with materials and smaller handmade items from my own dioramas. During the Tate Exchange event, I invited participants to work with materials to construct their own small-scale models of democratic learning spaces (Hoekstra, 2019). In Tate, visitors of various age groups worked to express in a material three-dimensional way both memories and ideals, using all sorts of materials and explaining what they did as they went along. The playfulness of working with small-scale dioramas created room for dialogue and subjectivity in a way that transcends our understanding of space based on sharing experiences and ideas in a verbal exchange.

Human geography does not only aim to speak about the subject of research in geographical terminology, according to Taylor (2009), but also to investigate this in its material, embodied aspects. There is a difference between education researchers that are fluent in geographical language, and “education researchers having the tacit knowledge to practice or “do” geography” (Taylor, 2009, p. 652). Although I have not yet found a methodological underpinning for the assumption that this makes arts-based education research a valid method to research the geographical dimensions of studio spaces for children, it is through combining these two relatively young research methodologies that I suggest investigating the physical presence of studio spaces and the important role they can play in our understanding of a pedagogical thirdspace. Arts-based research methods and human geography work similarly in the way knowledge becomes embodied in place and space.

A geographical investigation of children’s studios includes multiple perspectives on space and place that work together to create a layered understanding of children’s studios. Summarizing, we might look at aspects of interior design, the position of the studio space in the school building and the demographic and geographical qualities of the neighbourhood and the cultural ecosystem of the city area. The aspect of position can inform us about accessibility, visibility and the role of the studio in the school community. Questions of accessibility or porosity (Sennett, 2017) imply that the question can be asked whether the architecture opens to the outside. How does the physical presence of the studio invite or include communities to participate? This might shed light on the power issues involved and the cultural capital required to participate. On the other hand, investigating this through the lens of human geography might also mean looking at the participants: their movements, their agency in the space and their physical representation. Assuming that every type of space in some way directs the movement and autonomy of the body, how is the body disciplined by the space? On the other hand, the body can also be invited to move and participate by the physical/spatial aspects of the studio. It makes a difference whether materials are locked away in storage rooms and need to be asked for or are laid out openly for all to choose from and placed on low shelves easily accessed by small children. The arrangement of furniture and materials expresses who is allowed to take initiative. In Reggio Emilia the physical environment is considered a third pedagogue (Moss, 2001), next to peers and teachers who are considered first and second pedagogues respectively. The arrangement of the studio addresses the question of belonging. Looking at the studio from a children’s geographical perspective therefore implies looking at the way the space relates to the bodies inside. Other points of focus address the way in which the space is designed to facilitate disciplined practice or opens up to create hybrid and transdisciplinary practices. A third space needs to be ambiguous (Wilson, 2008), and I wonder what this implies for the physical qualities of the space. How is room for negotiation made tangible?

Lastly, I would like to refer to the notion of a children’s public sphere (Negt& Kluge, 1990) and the way the studio actually becomes a space owned and negotiated by the children. Inclusion of all children can only be established if pre-existing hierarchies are challenged. Physical-spatial arrangements like the absence of a teacher's desk and the arrangement of seats in a circle make this renegotiation of the public sphere possible. “Spatial arrangement is important as all practices are performed in relation to their location” (Krauss, 2015, p. 14). The question remains unanswered as to what kind of spatial arrangement it takes to create the possibility of a democratic inclusive studio space for children for a third pedagogical space to come into being.

Conclusion

Since the symposium, months of continuous pioneering in the Gastatelier have gone by. We have had many experiences to reflect on and are progressing in our aim to find our place in the community of children and families, the school and the neighbourhood. The artists in residence have sometimes struggled with the hybrid position of being artist-pedagogues (Petrie, 2019) but they have also experienced another way of connecting to younger children, and they have worked on their own wonderful artistic research projects: theatrical performances, playing sessions, newspapers, a publication and a pop-up exhibition. The children have been our greatest supporters throughout, swarming the Gastatelier with incessant commitment. We have seen a solid group of regular visitors and a large group of children that join the Gastatelier every now and then. Children come with their friends, alone or with their brothers or sisters. They bring different languages, different ages and different personalities with them. Some come to make, some come to play. And some come just to be there. Of course, we are not a democratic community yet, and this goal can only be met by continuing to develop the project, but we are working on it.

The experiences of the past months also confirm the richness of knowledge that I assumed I would find here. On the one hand, the specific place and space of the studio have implications for our ways of being together in Gastatelier, while on the other hand, the community makes its own demands. In committing to Negt & Kluge’s (1990) call for flexibility in order to make a childrens’s public sphere possible, we are forced to constantly reflect on all of the geographical aspects of the studio. Sometimes Gastatelier almost seems to be part of a territorial warzone, where every bit of surface is taken over by paint and cluttered materials. There are times when I wonder if we will ever reach an agreement on the question of who is a host and who is a guest. Even the most informal educational setting has a hidden curriculum expressed in physical objects like chairs and tables, open and locked cabinets and favoured spots for sitting.

Flexibility can also be sought by organizing events and activities. In May 2023 we organized a double activity for the neighbourhood: Give&Take (Geven&Nemen). Firstly, we held a donation day, where we invited everybody to bring scrap materials and redundant art materials to the studio. A week later we offered all our surplus materials by creating a give-away-shop where children and their families could shop for creative materials for free. We opened the doors, served coffee and tea and invited everybody to come. Making the space open to the public, in a way that was highly accessible for both children and their families, was an enriching experience for us as artists. In the framework of Documenta fifteen, curated by the Indonesian collective ruangrupa in 2022, the connection between the artists and the community is symbolically represented by the concept of lumbung. Lumbung is a traditional granary (for rice) in Indonesian agricultural communities. The concept represents sharing, because the rice harvest that is stored in the lumbung is brought there by those who can spare it and is accessible for everyone who needs it. In artistic connective practice, lumbung symbolically represents the sharing of artistic action with the community (Hubner, 2022). Gastatelier reminds us of the concept of lumbung in the way the community's shared harvested materials become collective goods. Our event Give&Take followed the method of collecting and sharing quite literally. Firstly, we called upon the neighbourhood and our own network to bring materials to our makeshift ‘recycle centre’ and a week later we reorganised all the materials we had in abundance to host a giveaway-shop. We opened our doors and provided free plastic bags that everybody could fill with what they needed or wanted.

This brings me to formulate some concluding remarks on the possibility to understand the work of Gastatelier de Vindplaats within the framework of Artistic Connective Practices. Hübner and his team (2022) argue that the role of the artist’s work in relation to society cannot simply be sought in the domain of creative problem solving, but lies much more in asking questions and developing ‘imaginative proposals, speculative imaginaries towards an environment, a situation, community or context” (p. 13). For the conceptual aspect of Artistic Connective Practice to reach out to the community and really make connections possible, both the artistic and the connective have to be brought into practice. Being in the school and in the neighbourhood of Gastatelier on a regular basis, doing the work not just for the community but with and in the middle of the neighbouring community enables us to share what we have with whoever needs or wants it. We experience this not as a one-way process, but as part of a process of reciprocity. Work is developed in and about the community of the Gastatelier. The work we do could not be done without being able to engage with the children, their lives and their families.

Gastatelier de Vindplaats as socially engaged practice

A few weeks before the symposium in November 2022, the doors to my project Gastatelier de Vindplaats opened. De Vindplaats is a new school in the Bos en Lommer area in Amsterdam, a neighbourhood faced with a changing population, where middle class families have increasingly moved away and the divide between lower social economic classes and young urban professionals has become more tangible. The new school building aligns with the developing pedagogical concept of an integrated inclusive child center, combining primary education, special needs education and childcare in one. The design of the building also includes a rather large empty room in a prominent position near the entrance of the building. In this empty room I was asked to create an informal shared studio space for artists-in-residence and children as an inclusive creative space in this neighbourhood school building.

There seems to be a growing interest in creating art studio spaces in schools, both over the short and long term, as part of children’s learning environments. In primary schools, which often don’t have specialist subject classrooms, art studio spaces might enhance the possibilities for art education. However, especially in neo-liberal society, facilities for children are often designed based on the assumption that children are limited to the role of fulltime learners who need to be educated or of consumers who need to be entertained (Illich, 1970; Giroux, 2021). This leaves little room for places where children are able to participate and have shared agency based on equality. I therefore propose inquiring into how the spatial qualities of the studio enhance the creation of a children’s public sphere (Negt & Kluge, 1990) or a third pedagogical site (Wilson, 2008) where pre-existing hierarchies are questioned and the inclusion of all involved is made possible (hooks, 1989):

A pedagogical thirdspace is a place in the margins with radical openness for democratic pedagogy. The thirdspace aligns with radical thought in postcolonial theory (Soja, 1999) as well as in feminist theory (hooks, 1989) because it opens up a public sphere for marginalised groups (Negt & Kluge, 1990), where dominating hierarchies are challenged and a voice is given to all those participating which are otherwise ‘othered’ or silenced (hooks,1990; Rancière, 2004) (Hoekstra, 2018, p. 247)

Gastatelier is a way to propose an alternative reality as a form of socially engaged arts practice. The keywords to describe the aims of Gastatelier de Vindplaats are accessibility, democracy, sustainability, and participation. It is, lastly but distinctively, an artistic residency where artists are allowed time and space to ‘engage in the context at hand, from a socially engaged perspective and through the perspective of artistic connectivity.’ (Hübner, 2022, p. 33)

Conceptual framework

South African artist William Kentridge (2014) argues in his lecture series Six Drawing Lessons that the studio must be considered a central concept in artistic practice. And although traditional studio practice has been subject to critique when associated with an individualistic perception of artistry, the artist studio has survived a critical period described as ‘post-studio’ and has developed into a more hybrid and collective model of artistic practice (Fraser, 2016). It is this hybrid and collective nature of artist studios that resonates in the children’s studios in Reggio Emilia. The established heritage of Reggio Emilia pedagogical practice does not confine itself to inspiring educators and pedagogues worldwide (Moss, 2010), but can also be of great value for the establishment of socially engaged art practices. Helguera argues that artists who want to work collaboratively would “well be served by following the roads traversed by these and other educators” (2011, xiii). And while Reggio Emilia’s early years practice has reached substantial audiences, there is even more to be learned from Room13’s democratic studios, where children work in collaboration with artists (Adams & Owens, 2016). The international network of Room13 studios, the first of which started in Scotland in the 1990’s, is characterized by a high degree of children’s agency. Often localized in schools, these studios function like collaborative artist studios where adults and children collectively take responsibility for the work done in the studio. Room13 must therefore be considered an exceptional example of a pedagogical thirdspace, which informs a radical way of thinking about inclusion and democracy in education (hooks, 1989).

Spatial metaphors - of a liminal space, a space in the margins between existing domains - challenge us to investigate the physical-spatial aspects of the democratic studio. Thinking about human existence in terms of space and place is the domain of human geography, which examines the complex interrelationships of social, historical and spatial dimensions. According to Edward Soja (1999), the spatiality of human existence has long been overlooked by academics. The study of human life focuses too predominantly on the historical and the social aspects of our existence, ignoring the geographical dimension. Space, however, is not a neutral given, but a social construction, according to Taylor (2009). Place and space also play an important role in education, but those physical-spatial aspects of education are wrongly underexposed (Sagan, 2008) because the focus in education lies too much on temporal aspects and curriculum. The important role of the pedagogical space does not only concern aspects of architecture and design, but also the physical presence of all those involved, something I encountered in my doctoral research (Hoekstra, 2018) and that I found to be little researched. Physical-spatial aspects of education are of great importance, especially for art teachers (Van Meerkerk, 2020). The significance of space and place for human existence is the subject of study in human geography, which can provide a tool for mapping the presence and ownership of children and learners (Taylor, 2009; Kraftl, 2013). The artist studio in particular, as a physical-spatial metaphor for an alternative learning environment (Masschelein & Simons, 2013), would lend itself well to art educational research on the importance of place and space and the complex relationship between space and pedagogy. How can we visualize the complexity of the studio space as an alternative learning environment on the basis of theory about the studio space, existing studio practices and development processes for artist studios inside and outside the school? How can we contribute to knowledge on the implications of the physical-spatial learning environments of children and the way in which informal art education practice can help understand the importance of rethinking educational spaces? This brings me to the need to employ artistic research methods when working with concepts of space and place, which is especially appropriate as a methodology when working with children (Hickey-Moody, 2021).

Click here to find out more about our project

Top: Small-scale diorama democratic learning spaces

(original work by the author)

Right: Interactive installation Tate Exchange Liverpool, March 2018