Axis is a UK charity supporting artists with an online platform. Available at: https://www.axisweb.org/about/ [accessed 17 Jan 2024].

Achthoven, Juriaan, Connective Symposium Documentation and reflection of the first and third day of the Connective Symposium organised by Professorship Artistic Connective Practices, 17-19 November 2022 at Fontys School of Fine and Performing Arts, in Tilburg. Unpublished text.

Beech, Dave, ‘Include Me Out’, Art Monthly, April 2009.

Beinart, Katy and Lloyd, Lizzie, Acts of Transfer, Social Art Publications 2022

Bishop, Claire, ‘Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics’, October Vol. 110 (Autumn, 2004).

Bishop, Claire, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship (London: Verso Books, 2012).

Bourriaud, Nicholas Relational Aesthetics (Dijon: Les Presses du réel, 2009).

Connective Symposium documentation in text and image. Unpublished pdf. 2022.

Hübner, Falk, in conversation with Katy Beinart and Lizzie Lloyd, 12th October 2023.

Ingold, Tim, Knowing from the Inside: Correspondences (Aberdeen: University of Aberdeen 2017). Available at: https://knowingfromtheinside.org/files/correspondences.pdf [accessed 20 March 2023].

Jancovich, Leila and David Stevenson, Failures in Cultural Participation (London: Palgrave Macmillon, 2022).

Kester, Grant, Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004).

Rendell, Jane, Site-writing: The Architecture of Art Criticism (London, New York: IB Tauris, 2010).

Rendell, Jane, The Architecture of Psychoanalysis (London, New York: IB Tauris, 2017).

Taylor, Diana, The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003).

Theodoridou, Danae, CONNECTIVE SYMPOSIUM Notes, 17-19.11.22. Unpublished document. 2022.

Our overarching aim in this exposition is to map the presentation of a socially engaged art project through an event that was part-presentation, part-workshop during the Connective symposium. The project we were presenting was called Acts of Transfer (2021) which concerned itself with the documentation, representation, and legacy of socially engaged art projects. How – through forms of social, emotional, physical, psychological and conceptual transfer – could we investigate the impact of socially engaged artworks that have taken place in the past? How can we conceptualise the original context in which an artwork was made, and connect it to present contexts and audiences? How do we understand, engage with and assess durational projects that we have not experienced first-hand, through returns, re-enactments, repetitions, and retellings? Key to our work is the question of legacy in socially-engaged artistic research, and how the artist, artwork, participant, site and audience continue to remain connected (or not) after the duration of the project. How, through the lens of transfer, can we better understand the ongoing impact of a work of socially engaged art on its creators, participants and audiences?

In presenting this work to the Connective Symposium we asked ourselves: What form might a socially engaged presentation about a socially engaged artwork take? How could the form of the presentation and also the workshop activities that we devised, not just tell our audiences about our project but embody, to some extent, the feel of it? We made a decision early on that each time we were invited to present about Acts of Transfer we would never just repeat something we’d done before. Each time we talked about it we wanted it to be a new iteration, for the presentation to develop the idea, to take us into new territory, without knowing where that might be.

Approaching this exposition, we wanted to demonstrate – visually, socially and spatially – rather than just explain in words, what the spirit, feel and experience of Acts of Transfer has been. Here, you will find a series of short texts that touch on various themes that have emerged through doing this work. These we imagine you reading, not from beginning to end, one leading on to the other, but as a constellation of thoughts that orbit the larger Acts of Transfer project and the role that connectivity has played in it as well as in events that we have held to present Acts of Transfer to others. Floating questions – that we have asked ourselves or others or both – scatter the scene like space debris. And images, drawings and sound files are interspersed throughout lending a multi-sensorial approach to your engagement. Sentences you will see partially repeated, and scenes described again and again, from different angles.

In what follows we use the pronoun ‘we’ without reference to specific names, except in our footnotes. We do so, not to signal a unified, smooth, uncomplicated position of inevitable authority, as has so often been the case with the use of the word in academia. Instead we use it to communicate an inherently fractured, bodily, uncertain sense of ourselves as makers, interlocutors, researchers and friends. Our we looks askance at the ‘critical distance’ that still holds much sway in academia. ‘For far from studying with the world, or allowing themselves to be taught by it, [academic scholars] make studies of the world, claiming in so doing to have reached heights of intellectual superiority from which things are revealed with a clarity and a definition denied to ordinary folk’, writes Tim Ingold. He goes on ‘This sovereign perspective requires of academics that they keep their distance from the matters of their concern, and do not get their hands dirty by mingling with them’ (Ingold 2017). Our we happily mingles with our research. Our we celebrates its irregular and inconsistent thinking. It jumps around, queering space and time and how different ideas relate to each other. Our tenses slip: we think back but also forwards, and also back as if the past hadn't yet happened. Sometimes our we disagrees with itself, or agrees wholeheartedly, or isn’t quite sure. Our voice, voices differently throughout this exposition. The externalised internal dialogue – thinking aloud – that appears here has been integral to the connective way in which we have worked in collaboration with each other and with our participants. We are not always sure who we is; who we are. We are not always sure who’s who. Sometimes our we might implicate you. Sometimes, others who we have met along the way. During the symposium our we was sometimes ourselves, sometimes our audience, and sometimes our co-participants.

We went first. We decided in advance that we would develop a presentation that performed two roles. It would act as a means to discuss the points of overlap between our project – Acts of Transfer – and the symposium – Artistic Connective Practices – but we also saw our contribution as performing the important role of an ice breaker, as our session was the first one, on the first day. We’d get to know each other while doing something that was relevant to the theme of the symposium, which was after all why we all found ourselves here in the first place. We’d offer the possibility of aesthetic and physical distraction as conversation began. Because, here we all were; here we all are. A room full of expectant participants, mostly strangers, descended on Tilburg from Brazil, the UK, Crete, and beyond, all here to not just talk about but enact connective practice.

We wondered how we would discuss Acts of Transfer through the lens of connectivity. We weren't interested in just telling people about the project. We wanted them to feel it, we wanted to connect them to the project through an experience generated by the fact of our sharing a room together. Now. But before we get there, we think we’ll need to set some sense of a scene. We can’t just drop them in it.

We’re dropping you in it. We scan the space now in three dimensions instead of two. The space in which we worked together in the symposium would, we knew, in many ways define the nature of our new connections. We had asked for images of the room in advance. We imagined ourselves there. When we arrived, in three dimensions, it was smaller and there were more chairs than we had anticipated. Or at least the ratio of chairs, our bodies, and the bodies of yet-to-arrive participants to floor space was greater than we had imagined. The green of the carpet was greener. Two lines of slim columns cut the room into three, separating the middle portion from the sides and developing the sense of a larger central aisle where chairs fitted but snuggly. The space was also a library, bookshelves extended to the high ceiling on one side and a wrought iron balustrade delineated a narrow balcony like a viewing platform which suggested a bird’s eye view of the proceedings.

So we begin by passing paragraphs between us. We stand together, at the front, side by side.

Here we split. One of us reads; one of us wraps. One of us paces; one of us surrounds. A film plays out.

Connection also played out temporally. In concerning ourselves with participatory artworks from the past, and returning to them (or an iteration of them) in the present, Acts of Transfer (2021) saw us constantly moving between the past and the present with a view to potential future legacies of ours and our collaborators’ actions. Relationships between the original and the return, and the partial reenactments recurred, becoming increasingly heightened and complicated.

Reflection has been a key component in how we have worked. Reflection is a kind of bending back, a reflex. It generates a buckling and stretching out of the relationship between time and action. We did; we thought about doing; we planned to do; we thought about doing differently. Working as a collaborative duo in Acts of Transfer meant that we enforced a regular, scheduled reflective practice (which would have happened in a more intuitive or ad hoc way had we been working individually) built around that movement between past, present and future, where the three collide, overlap, fold over and break apart. We built reflection into every stage of our collaboration. We noted that this was interesting as other spaces of collaboration that we’ve been involved in have been different, and often less reflective.

Time worked differently then. We began at a time when time passed gloopily during the pandemic. Time was lost. Time became static. Time was short. Time was long. Time stuttered. Time fractured. Time was irregular, characterised by gaping holes and intense pressure. The design of our Acts of Transfer book tried to encompass this. Gradually as a semblance of normality grew, time settled, time regulated. Time during the symposium had another character altogether. Here it was compressed. There was so much to get through. Time here was intense and full, unlike the spaced out nature of other parts of our work. Here, we had so much to say and all at once.

Something that we had been acutely aware of while developing the Acts of Transfer project was the space in which we met other artists, the spaces in which we worked together and the spaces of galleries where we had exhibited or led workshops or talks. As well as the space of the pages of the Acts of Transfer book (2022) that brought our project together. But we were also interested in how to capture the spirit of conversation and connectivity through conversation in our work. We thought about this a lot, throughout the whole Acts of Transfer project, but especially when we began filming and photographing. At the beginning, we filmed with a ‘talking heads’ approach, but quickly moved away from that. Talking heads felt too direct or formal, too reliant on verbal communication. Instead we wanted to come at things from the edges. We started to realize that there was a pattern of decentering. We started, for example, to think much more about the spaces in which we met our participants, and the edges of the space in which we were talking. We looked at the ground, and at the corners and at the furniture and at the wires and kit we’d brought with us.

As our confidence about the project grew we noticed that we embraced movement and activity above static verbal conversation. This less direct, less literal, approach gave us a different sense of connection. We began to feel much more connected to what we were doing, and the space we were in, as if movement lent itself to a greater possibility of transfer than if we were still. So when we were moving and when we were walking, the focus became less about documenting a conversation and more about making a piece of work together. Coming back to Diana Taylor's work and the relationship between the archive and repertoire – between the document and the performance – we had to remind ourselves that the words people use and what people say have historically held too much weight in Western academic practices. Instead, we wanted to enter into the physicality and embodied nature of revisiting the places and artworks as a means to seek out points of connection that in turn would lead to transfer.

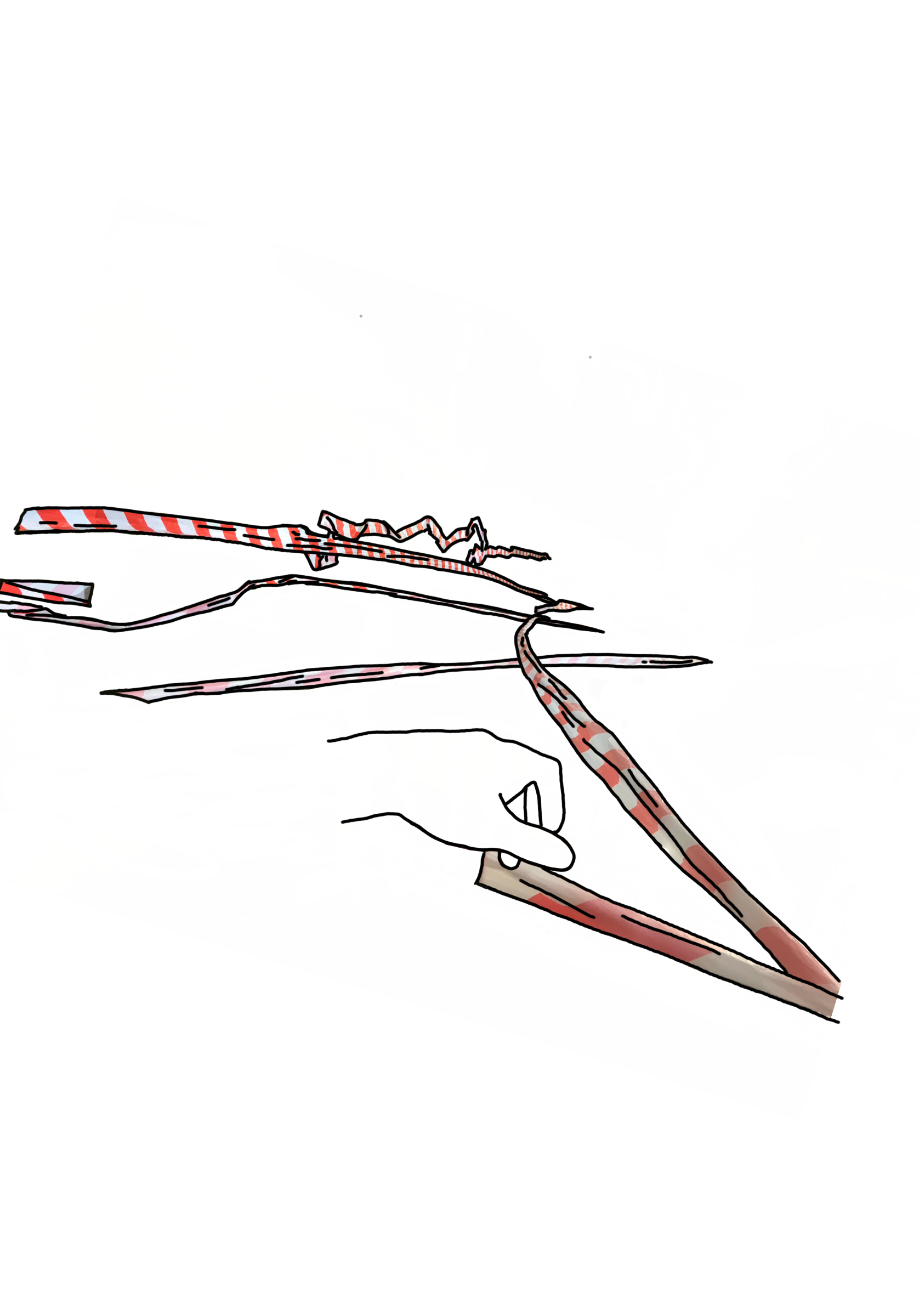

One of the questions that we posed during the Connective Practices Symposium was: ‘What’s the architecture of connection? What kind of space is conducive to connective thinking? What about this space - how would you rearrange it?’. In the symposium, we presented to an audience of people who were initially sitting in chairs in rows. This feels important. We started at the front together, side by side. We then separated, with one of us at the front, pacing back and forth and the other walking around the audience who sat in chairs that were contained within two lines of slim columns (discussed in On Simultaneity) that cut the room into three, separating the middle portion from the sides and developed the sense of a main central aisle. The chairs fitted but snugly within this central area. Armed with rolls of barrier tape one of us wound the tape loosely around these columns drawing and tying as the other read extracts from the book that we’d produced. Barrier tape felt like a way that we could change the architecture of the space and therefore also the relationship between our bodies to the space where we would spend the majority of the next forty-eight hours. As one of us began wrapping the tape around the configuration of chairs we sensed a feeling of discomfort. We were hemming people in (after months of pandemic lockdowns). This was barrier tape designed to keep people out, though we were using it to keep us in, to keep us together. Connecting people does not necessarily feel comfortable, in fact it can be fraught with anxiety. ‘I think I didn't love the feeling of being taped into a place or feeling like being in a box in some sense, feeling restricted’ (Thomas, 2023). It is not a wholesale act of goodness. It was complicated. We remember the energy with which people unravelled our makeshift construction at the end of the session. But it was also a form of binding that others appeared to embrace. It enforced a thinking through connection and a shared connective experience. By using the architecture of the room, winding around it, we redefined the existing barriers in the space more explicitly. To paraphrase one participant: this architecture of connection created a space for connective thinking. It became so you could not NOT relate to the space (Hübner, 2023). It became a ‘construction site’ for connectivity setting the scene for what was to come. A work in progress.

For the final stage, we set a task for groups of 2-4 people.

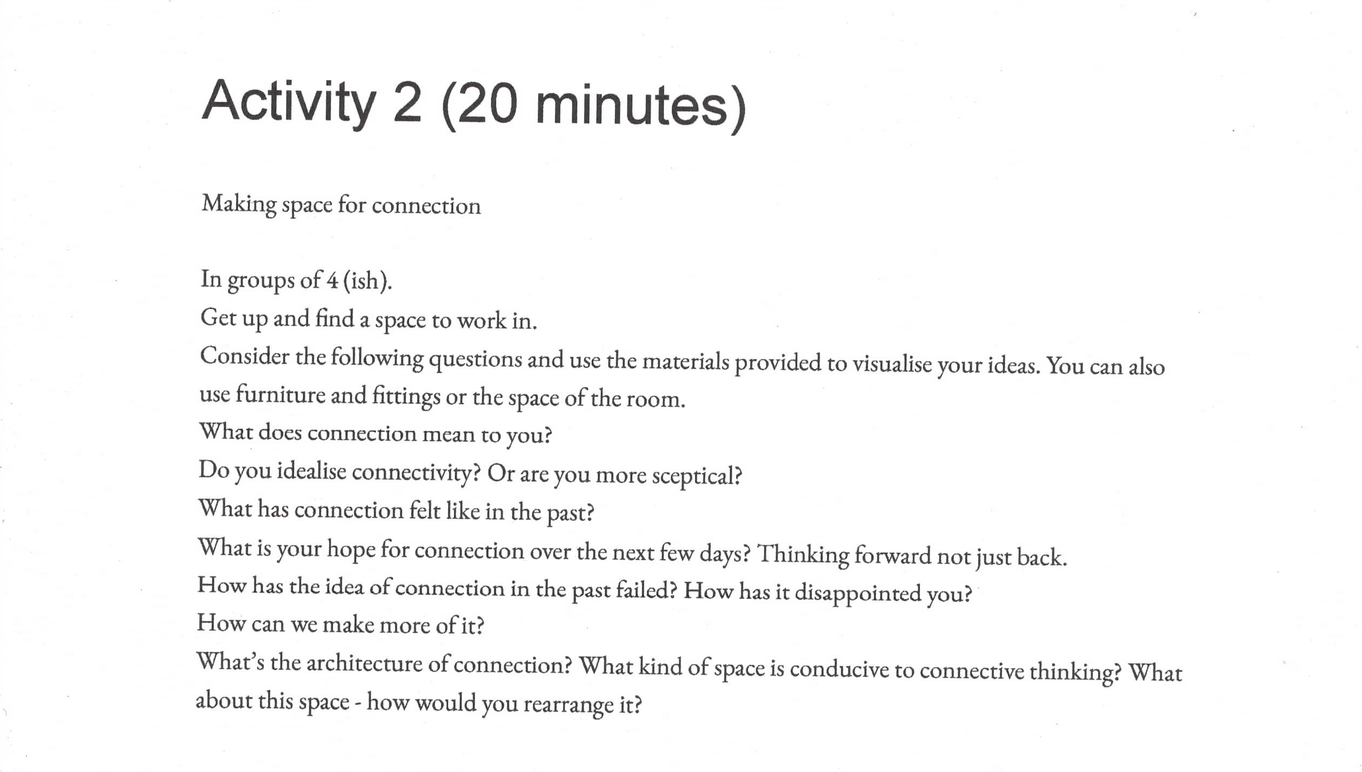

Activity 2: Making space for connection

What are your experiences of connection - past/present/future (20 minutes)

In groups of 4 - two pairs. Get up and find a space to work in. Use materials which we will have on a table - you can also use furniture and fittings/space.

Here participants moved out of the confines of the central space (more decentering!) to make space to work. Some formed groups around tables that were already set up on two sides of the room. Some stood, some sat, some leaned. Some clustered around a column on the floor in the back corner. Some made space in the centre of the room rearranging the chairs slightly to accommodate them. Circles were favoured here. Some took up the spools of thread and electrical wire and bulldog clips to create makeshift architectures that hung from the ceiling or formed other modes of attachment to various bits of furniture in the room. The binding barrier tape was broken, fell down, and became dishevelled remnants in piles on the floor. Instead of an enforced spatial connection by our use of red and white tape, groups arranged themselves spatially, and then used the materials on offer to help define their newly-formed conglomerations. Some experienced this activity through connecting spatially rather than verbally: ‘I found myself trying to create a structure out of materials while the rest of the group was connecting verbally; resonating with their words by listening not interacting’ (Connective Symposium documentation, 2022).

Others took the idea of connecting through the materials to give spatial form to the conversations taking place: ‘I think I was mainly just chatting and maybe making something small. [They were] actually making something … around us and through us while we were chatting. She was joining links of different things, throughout us having the conversation and then she would … dip in and out of the conversation' (Thomas 2023).

But were our co-participants really with us? Do they need all this? We have made judicious eye contact, paused at regular intervals, exaggerated the lilt of our voices all in an effort to find a hook with which to join ourselves together here, to be thinking not just alongside each other but really connecting. But what other approaches could we take to think together differently, to communicate the feeling of the project without just a retelling in words. We talked about what materials might be conducive to this communication beyond paper and pens. We landed on barrier tape and electrical wire, bulldog clips, and electrical tape. These materials were chosen for how they could be easily manipulated by nervous hands, skilled or unskilled, over a conversation with just one or two other people. We sought out materials that were cheap, and light enough to travel with, but that were connective as well, could join together and be joined, but also disconnected and reconnected, mirroring the possible imagined dynamics of our small groups as conversation emerged between our participants. We looked for materials that could perform the ideas that we were thinking about, that would allow us to communicate without undue reliance on voice or words.

At the beginning, before it even became Acts of Transfer, this project was about trying to make connections between our own and other people’s practices. We used projects that had some kind of participatory and/or socially engaged element to lend focus to this investigation. Something that we kept circling around was how to heighten our understanding of how the relationships that were inherent in participatory projects informed the resulting outcomes. How could the particular character of that participation be retained in the artworks long after the work had been ‘completed’ or performed? How could these projects be effectively communicated to people who were neither participants nor present in any other capacity during the making of the original artwork? How as authors, artists, participants or audiences can you, not just connect, but remain connected to a project especially when it is an event-based work of a fixed duration? It was not just about wanting to know more about these projects but wanting to feel some other, more embodied connection to them.

We came to Acts of Transfer from two angles, that of the artist engaged in making socially engaged work, and that of the writer discussing this work. We also came from a place of having viewed both exhibitions of work about socially engaged practice and writing about these practices. We shared a sense of lacking in what we had seen before: a lack of embodied connection to a project's ability to build social relations or connections between people through the work (sometimes called relationality), and a lack of aesthetic, material or emotional connection produced by the documentation of such work.

Writers writing about socially engaged practice including Nicholas Bourriaud (2009), Claire Bishop (2012), and Grant Kester (2004), have taken different views as to how the practice can best be evaluated or understood, a debate that famously took place across the pages of Artforum between Kester and Bishop. Bishop has written that Bourriaud sees ‘the work of art in this case as a ‘social form’ capable of producing human relationships,’ and that consequently ‘the work is automatically political in implication and emancipatory in effect’ (Bishop, 2004, p. 62). Here, the artwork produces social relations. For Bourriaud the way these artworks should be evaluated is primarily how the work generates and develops dialogue, but he doesn’t discuss the content of the connection being produced. In other words, for Bourriaud, the dialogic structure is the subject matter rather than what is produced by the dialogue). As Bishop says, the ‘quality of the relationships in “relational aesthetics” are never examined or called into question…so if relational art produces human relationships, then the next logical question to ask is what types of relations are being produced, for whom and why?’’ (Bishop, 2004, p. 64) Bishop suggests that rather than structures of conviviality, participation offers the potential for dissent and critique. Dave Beech, however, has pointed out that ‘the limitations of the whole enterprise’ should be intrinsic to these arguments. In other words, too much emphasis is being placed on the possibilities of social connection (Beech, 2009).

In Acts of Transfer we focussed on the value of what is being produced by social connections, relations and dialogue. But at the same time we were intent on not shying away from the difficulties inherent in making socially engaged art. Similarly, when presenting to symposium participants, rather than explain straightforwardly what the themes of Acts of Transfer were, and what happened during its making, we wanted to find a way to communicate how Acts of Transfer felt, and continues to feel each time we think about it. We were intent on presenting the value of socially engaged work and communicating the tensions inherent in it. We wanted to use Acts of Transfer as a medium through which to think about the symposium theme, designing a session that was part-presentation, part-performance, part-workshop that engendered an embodiment of critical considerations of connective practices. Our participants, we hoped, would move between passive and active participation, connecting to each other while giving space to acknowledge the personal complications and anxieties to which artificially induced connective activities so often give rise.

We came at Acts of Transfer from two angles, one as a writer the other as an artist. Very soon, these two positions became much more entangled. As time went on, we began inhabiting each other's spaces: we make, we write, we film, we photograph. We’ve been doing things that we might not normally do in our practices. In a sense, our understanding of connection and connectivity began with each other – we didn't know each other before working together. Our getting-to-know-each-other rippled outwards, overlapping with the process of getting to know the other artists and participants that we ended up working with, and of getting to know their projects. Giving focus to the tangible and intangible remnants of artworks, was about not knowing if there was a connection, or what that connection looked, sounded or felt like. We wanted to be able to picture that connection, to capture the feeling of that connection in the interrelationship between words and imagery that formed our own work on the subject.

We wanted to bring this same spirit of emerging connectivity to the first interactions that we set forth at the symposium and to this exposition that slips and slides across your screen as we speak.

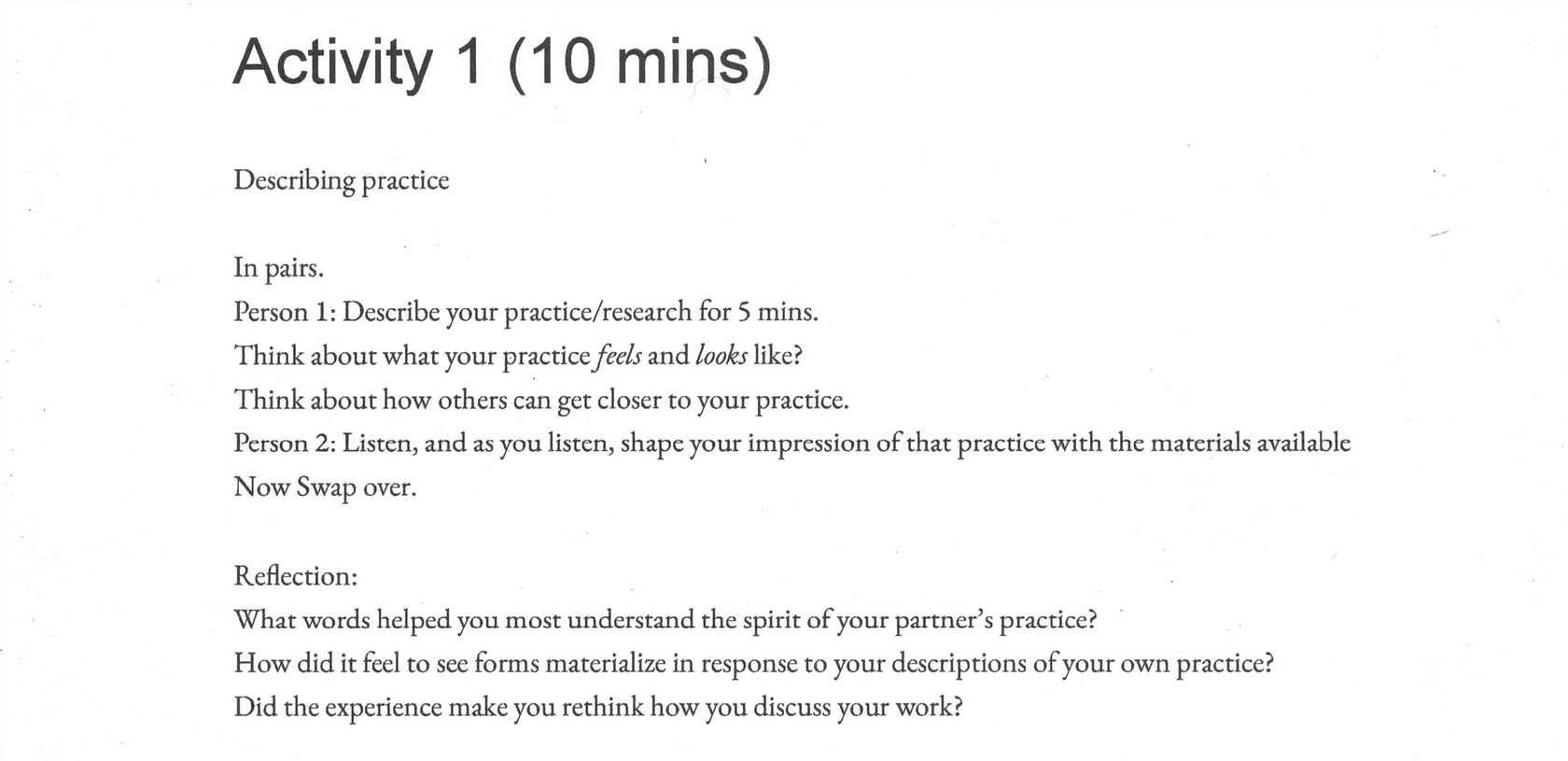

Activity 1 (10-15 mins)

In pairs. Person next to you - stay where you are. We hand out materials.

Person 1: Describe your practice 5 mins? Think about what your practice feels / look like? Think about how others can get closer to your practice.

Person 2: Shape your impression of that practice with the materials available

Swap over.

5 mins Reflection:

What words helped you understand the spirit of your partner’s practice better ?

How did it feel to see forms materialize in response to your descriptions of your own practice?

Did the experience make you rethink how you discuss your work?

The combination of doing and talking has long been known to support the easing of social interactions. ‘Artistic connectivity,’ wrote one participant after the event ‘in this context then seems to imply the activation of an aesthetic dimension in the intersubjective communication through the co-construction of visual forms’ (Achthoven, 2022). We hoped that this activity would not only break the social ice, but would get people thinking about what the words we use to describe our projects communicate to other people. What feeling emerges from this description? How do others visualise what you do, without the support of documentary images? What kind of transfer of ideas from one person to the next do words induce? One of our participants suggested that this activity was ‘a good tool [encouraging you] to figure out how to explain your own practice to somebody, within a certain context [and] picking and choosing what information was useful, and then seeing it projected back to you’ (Thomas 2023). We hear something anew.

We watch on as our participants speak, winding malleable wire around their fingers, nodding intently, making eye contact. One participant commented that ‘Seeing somebody else's physical representation or metaphorical representation of my practice was really nice’ (Thomas 2023). We are not a part of their conversations. We judge the success of this activity on the rising noise levels in the room, and the wire sculptures that are taking shape, being handled in turn. We have set off this series of interconnections which we observe from the margins. Regardless of how many workshops we lead, or classes we teach there is always a moment of uncertainty, a moment where we worry: is everyone engaging? Are they connected? And does it matter?

Was this a space where we and others could test things out and allow them to fail? The weight of expectation when you work in a way that foregrounds connectivity between different people and practices is strong. We felt this in both the Acts of Transfer project and also during the symposium. In Acts of Transfer there were expectations that people had for what we were doing, and when those things didn't necessarily match up with the reality, we worried that the experience was disempowering, for us and them. So there was sometimes a disconnect and actually that disconnect was difficult given that the whole project was about a kind of collaboration, and seeking of connection through the medium of the shared experience of an artwork. When we felt disconnected, it was almost impossible to do the thing we were trying to do and we found it difficult to make something from it. It made it really challenging. The reality is that these projects don't always work, and that people don't always actually enjoy being part of them. You want each thing you do to be valuable and it's disappointing when sometimes that fails to work. We have often wondered how to retain this sense of feeling challenged and disconnected in the final outcomes of the work.

But speaking about the limitations of connectivity in practices of social participation and engagement is so rarely done. Leila Jancovich and David Stevenson’s work in this area was brought to our attention through conversation with Lucy Wright, social producer at Axis (www.axisweb.org). Jancovich and Stevenson challenge ‘a cultural landscape that is not conducive to honesty or critical reflection about failures’ in which ‘feel-good’ narratives overstate the impacts and successes of participatory work (Jancovich and Stevenson, 2020). It’s not hard to figure out why this might be, when artists’ (and researchers’ more broadly) future funding – whether through universities, public funding bodies or organisations – is built on the evidenced successes of previous projects. So how could our work on the Acts of Transfer project (and subsequent presentations and conversations about our work) be honest about the limitations of the successes of our ability to always create connections that led to meaningful transfers of knowledge, understanding or emotional impact. How could we be honest about these limitations without doing a disservice to our various participants and their generosity and openness to working with us? And how could we be honest about our own need to feel that everything we did succeeded in some way, in developing our project, and furthering our understanding and so on?

And what about here in the symposium? One participant said: ‘where it resonated the most actually was with the questions that you posed.’ They go on to reference the presentation which ‘felt more like getting an idea of maybe how you guys work and what you're interested in and what drives the project rather than kind of the outcome or the interactions that you even had within the project’ (Thomas, 2023). A failure then, if you are looking for clarity of an outcome or overarching narrative, but maybe a success if you’re trying to communicate the essence of a particular way of undertaking a collaborative and connective practice. Perhaps more than anything else, awkwardness was the overriding feeling we were left with. One of us thought, we kind of had to just go through with what we were doing. And maybe there was a little bit of discomfort that we just had to do it. And I think maybe as we were doing it, that there was something a little bit awkward or that we weren't quite sure about what we were doing. We think that that was maybe something we were both feeling.

We didn't know it at the time but one of the groups responded directly to the question: ‘How has the idea of connection in the past failed? How has it disappointed you?’ They shared their notes afterwards: ‘What if we understand connectivity better through the way it fails? When does one’s effort to connect to someone become an imposed connection mode from the side of the other part, which may put strict limits and restrictions in terms of the connection between two or more people should take place? What is acceptance what is imposed mode of connection? ….What are the limits of connection? When does a community become restriction?’ (Theodoridou, 2022).

In the symposium, the timescale was so quick and our workshop was part of so many other activities and conversations, that we had very little idea of how successful or not the work had been. We asked a lot of our audience-participants: we asked them to switch between being consumers/audiences to active participants to active listeners to active makers all in the space of fifty minutes. One of us worried that we had tried to do too much while also feeling strongly that this ‘overload’ was part of the work. One of us felt that we needed more time to implement the performance with space and materials. The aim of our 3 part session was multi-pronged – to break the ice, to introduce some of the ideas of the symposium, and to present the relevance of our work through Acts of Transfer in relation to the theme of the symposium. Were our aims too many for the time available?

Did we leave enough time to set out the rules of engagement, where with each symposium presentation the rules of engagement shifted leading to an exhaustion of participation where we began to crave passivity and observation over engagement and taking part. And we wonder if participation and connectivity always has to be literally manifested. What might invisible, introverted connection or participation feel like? What might such a connection result in?

One of the key ways that we worked together was through a mode of simultaneity – doing multiple things at once. This manifested in a number of ways through the project and through our retelling of the project in the symposium. Throughout Acts of Transfer we were both in the project and aware of how our experiences might manifest outside of it. One of the outcomes was a series of films which we approached in a similar way to how we approached the Connective symposium and this exposition. We didn’t want to just document conversations, or tell people what happened. We looked for ways to make use of the possibilities inherent in the space of the film as medium, as a way to gather together different imagery, different perspectives, different sounds, and different conversations. Simultaneity allowed us to do everything at once: ask questions, respond, record, and observe.

Another outcome of Acts of Transfer was a book which we made in collaboration with designer Des Lloyd Behari. In it we layered photographs, film stills, captions, text, and drawing. We wanted these different modes to coexist on the page in a way that recognised the fragmentary imperfection brought by our perspectives. The interconnection between the visual and the verbal was a huge part of Acts of Transfer. One of us says: we spoke a lot about what the connection was between the visual element and the verbal element or the spoken and the written words. Back to transfer then, and Diana Taylor’s discussion of the embodied possibilities when we move beyond the confines of textual language.

We brought this simultaneity to bear in the symposium, too. Following our short introduction, we had one of our films playing in the background. Meanwhile, one of us read and dispersed pages from our book as we went. We read in fragments, without allowing the listener to settle, building a sense of multiplicity and confusion. ‘Louder’ we hear someone in the audience say. We pace back and forth as we read. Meanwhile, we unwound a roll of red and white striped barrier tape, weaving it around the columns of the room. We tucked and wound and draped the tape creating a kind of provisional ‘container’ for our participants. In our planning, we referred to it as a drawing. It ended up being noisier than we’d expected adding another barrier to our participants’ ability to ‘capture’ or understand the words being spoken by our reader and that were playing out concurrently on the film. ‘Sometimes,’ one of the participants told us ‘I would just be looking at you going around and maybe kind of forgetting what [they were] talking about and then jumping back in’ (Thomas, 2023). We were interested in the disjunctive synchronicity of this, of everything happening at once, leading to attention being pulled in different directions, making the cerebral comprehension of the performance almost impossible. This difficulty felt right. It might also have been frustrating. Or it might have allowed different kinds of thoughts to happen, not unlike when participating in or watching an artwork taking place before you.

Going into the symposium we had no control over how our workshop and presentation would be documented. Beyond a few snatched phone pictures what remains of the event are a series of images, notes and thoughts captured by others. We have pieced them together here, along with reenactments of actions we only partially remember, and some words we read out. Drawing on these inaccurate traces of memory is, of course, another act of transfer. The presentation of this exposition is yet another way in which we make explicit this piecing together of our understanding of the Connective Symposium. The constellation of short texts can be read in different orders, they exist across the same plane, the same page of the Research Catalogue. As with all of our work for Acts of Transfer, here we are looking not just to illustrate but to embody our thinking. Here our memory work is one of remaking, looking to undo definitive knowing, and the construction of definitive connections by the unreliability and decentering of our narration and representation and inevitable repetitions.

The nature of connection in our work revolved around an idea of ‘transfer’. We had read about transfer in the work of Diana Taylor, whose book The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas proposes that performances can be ‘acts of transfer’ which embody knowledge (rather than the western privileging of the physical archive as knowledge) (Taylor, 2003). We used Taylor’s work as a starting point to imagine an expanded practice of documenting socially engaged and participatory practice. We saw transfer as manifesting in 3 overlapping ways: 1) between the artist and participant, 2) between artwork and audience and 3) between the legacy of the project (often in the form of documentation) and audiences engaging with that legacy. In Acts of Transfer (2021) we attempted (partial) re-enactments of artworks, in collaboration with the artists and participants, to create forms of documentation that foregrounded the transfer inherent in the work.We are beginning to situate our understanding of transfer in relation to Jane Rendell’s work on transference, in which she uses psychoanalytic theory of transference to position the critic between the artwork and the audience, and to conceptualise questions of relation in criticism (Rendell 2010, 2017). Transfer has the potential to be generative rather than duplicating an original. In our re-makings of previous artworks, we were not attempting to create exact replicas of a previous event but rather through the gaps and differences to understand where the transfer was, and had been, for artist and participant.

Initially, we had no title for our project, and we were using terms such as unsettling, and unmapping to apply to the practice. We were attracted to the looser and more poetic possibilities of transfer, the way that some kind of connection between two or more parts leaves its mark, losing the possibility of separation (like our ‘we’). Sometimes we could identify these as actual, physical connections, at other times something more emotional, invisible or imagined. It could be something communicated quite subconsciously, or accidentally. It could be a byproduct of an action, not necessarily an aim. We looked at traced lines of a walk on a map, at polaroid photographs, at quotes shared, and landscapes imprinted by our presence.

In the space of the symposium workshop, transfer happened both at the time of the event and afterwards. The physical objects people made during the session became ‘acts of transfer’, in the sense that they took form hand in hand with the conversations taking place. We saw the objects as acts in themselves, like oblique visual residues or manifestations of verbal conversations. The connections made through conversation in pairs and groups were acts of transfer, setting up relationships and knowledge which then informed the future sessions and activities over the three days. And the continuing connections after the event ended have enabled further forms of transfer to continue

We thought about what had helped us to interrogate where ideas of connectivity had surfaced throughout our experience of the Acts of Transfer project. We developed a series of questions which we posed to our co-participants about their experiences of practices and projects which might be termed connective. These questions were key because we were keen to not just embrace, uncritically, the idea of connectivity, social practice and participation in artistic practice. But we also understood the potential power and attraction of the relationships that are created through these connective ways of working. The lure of community is strong.

We used the form of the question as a way to pose some of these problems without confrontation. We asked:

What does connection mean to you?

Do you idealise connectivity? Or are you more sceptical?

What has connection felt like in the past?

What is your hope for connection over the next few days? Thinking forward not just back

How has the idea of connection in the past failed? How has it disappointed you?

How can we make more of it?

What’s the architecture of connection? What kind of space is conducive to connective thinking? What about this space - how would you rearrange it?

We had come to this work intending to unsettle and break open how participatory work is described and packaged. We wanted to try to get to a more honest understanding of the aims of such work, how it was experienced at the time and what remains of it after the fact. That meant that sometimes the questions we asked were tricky. Bringing these thoughts to the symposium, we wanted to be able to ask open questions that might expand discussions around what artistic connectivity means as a term or concept, rather than just assume that practices that seek out connectivity with people and places are inherently good. We were aware from experience that participatory art is sometimes instrumentalised, where differences or difficulties are smoothed over, and that connectivity also had the potential to be co-opted for strategic purposes. The questions we posed were meant to help us all understand the different agendas or strategies within the event, what position these took, and how they felt.