Ten Years with the Journal for Artistic Research

Impact and Challenges

13th SAR conference 2022

Bauhaus-Universität Weimar

The session was introduced by Henk Borgdorff, who had been a JAR editor as well as president of SAR. Various editors were present during the session, others contributed materials that were screened. Unfortunately, there is no recording of the session itself.

Editor in Chief: Michael Schwab

Managing Editor: Barnaby Drabble

Peer Review Editor: Julian Klein

Editorial Board: Annette Arlander, Carolina Benavente, Danny Butt, Yara Guasque, Siham Issami, Paul Landon, Manuel Ángel Macía, Helly Minarti, Barbara Lüneburg, Mareli Stolp, Reiko Yamada and Mariela Yeregui

Interns: Libby Myers and Costanza Tagliaferri

Associate Editors: Michael Hiltbrunner, Elisa Noronha and Jesús Fernando Monreal Ramírez

Good afternoon. My name is Barbara Lüneburg. The title of my contribution today could be "Knowing Through Worldmaking –or– Why I Love Working at JAR"

Before I start my short talk, I would like to point to the videos by Geneviève Sicotte which are running in the background. They are taken from issue 26 of JAR. The original comes with sound, I have muted them while I am speaking. Therefore, please visit JAR later to get the full experience.

I look at artistic research from different perspectives.

As an internationally performing violinist and artist I use artistic research to better understand and further develop my own artistic practice and nourish the discipline I work in.

As the director of the doctoral programmes at the Anton Bruckner Private University in Linz, Austria, I introduce artists to a systematic, exploratory way of thinking that guides them reliably and transparently through their doctoral artistic research project. Transparency in what is asked of them is important, but it makes the approach to artistic research within the programme possibly a bit more regulated than for instance in JAR.

As an editorial member of JAR I am explicitly willing to embrace uncertainty and novelty. Here I can ask: What else can artistic research be? How can knowledge be articulated? How can it be felt, heard and seen?

I look at the expositions that are presented to us, marvel at the diversity of approaches. I wonder what is being said, what is being learned, who is talking about what and how?

Take for instance the videos by Geneviève Sicotte you see here.

I ask myself what kind of worlds does she make for us? What knowledge does she want me to find in them and how do I understand what I see, read, hear in these worlds?

Where does knowledge start?

Where does it end?

How is it understood?

Who is allowed to talk?

We can explore this in JAR.

Barbara Lüneburg

Siham:

Why a French language panel in JAR ?

1- Accessibility

The francophone world is a large one; 29 countries have French as their official language; the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie (OIF) count 88 member states, and alongside English it is the only language spoken in all 5 continents. So we are opening up to a significantly large part of the artist-researchers community in the world, as well as to a larger readership.

2- Diversity

The majority of the world's French-speaking population lives in Africa, spread across 34 countries: Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Gabon, Congo, Senegal, Ivory Cost, Mauritius… etc. Each one of these countries, although sharing the language, is culturally different to the others. So the French language allows us to have access to a large mosaic of cultures and ways of conceiving art.

For the language in itself / there is no form of thought that we know of outside language / opening up to different languages is opening up to different ways of thoughts. (en francais on dit que le mot choisie sa pensée)

3- Participating in establishing the practice where needed

It is problematic that studies of arts, up to this day, in francophone Africa, are in majority affiliated to the Ministry of Culture and not the Ministry of Higher Education. By encouraging submissions in French we are in fact participating in creating the demand for the practice of art as research.

4- Exchange /Parallel/ Dialogue

Having five languages in JAR side by side allows interferences and forms of dialogues. It also allows parallels and paradoxes for artistic research through the prism of different languages; a language in this case is really a sort of prism, some rays go through some not, some other are distorted or develop other shapes; it is by itself an artistic research if you will. All those main axes: accessibility, diversity, dialogue and establishing practice are of major concern to us within JAR and adding a French language panel contributes greatly to their development and to JAR's Growth.

Paul :

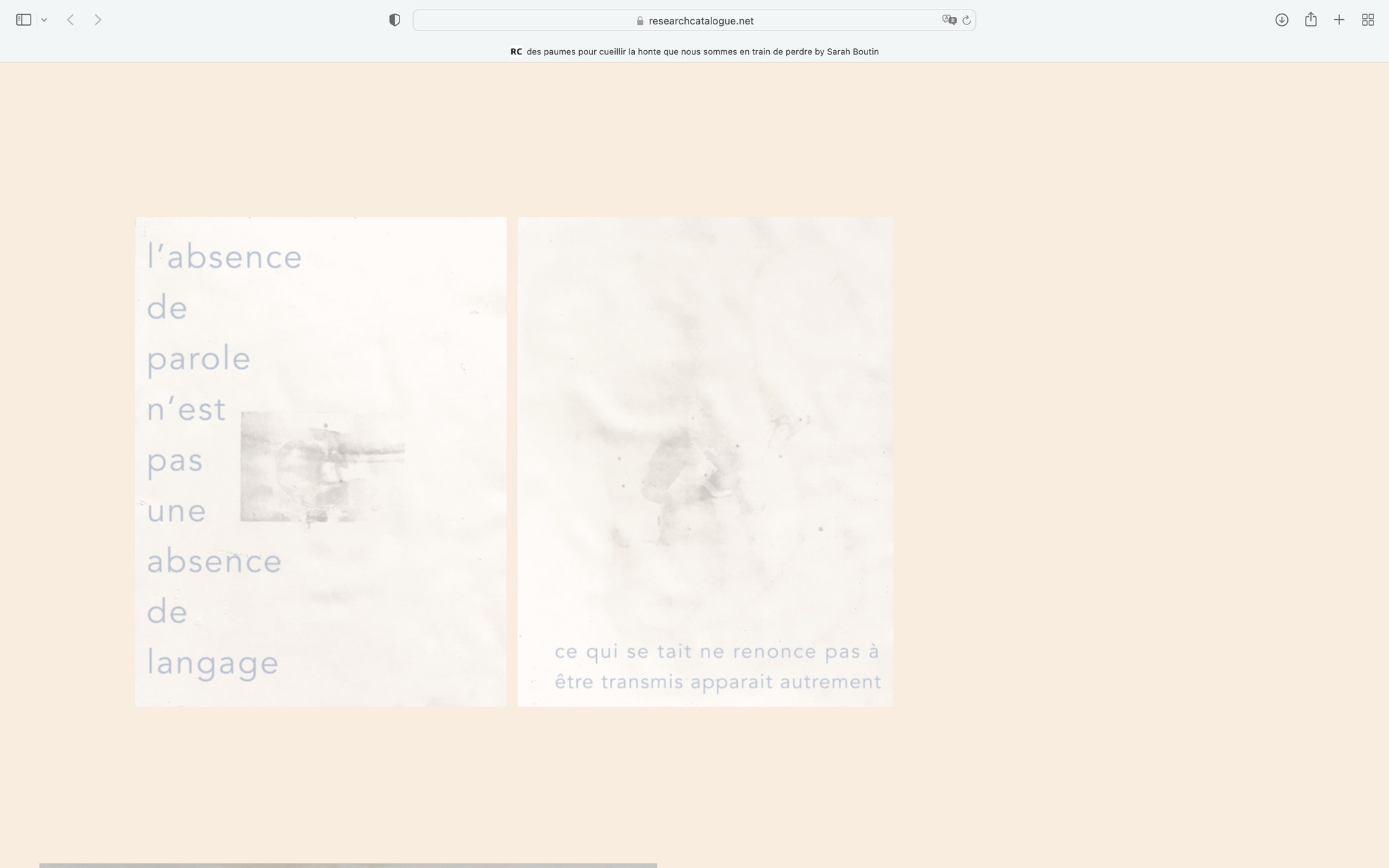

Siham referred to the dictum « le mot choisie sa pensée » or, roughly, that words determine thoughts. When considering terms specific to a language we can look to the concept of recherche-création, developed in French speaking Canada. One explanation of the term is one used by the filmmaker and researcher Serge Cardinal at the conference, La Recherche-creation territoire d'innovation méthodologique where he said, « a research-creation approach is based on an intrensic reflection in the development or in the production of an artwork. » In the slideshow are pages of some projects of recherche-création developed for the Research catalogue by my students at the École des arts visuels et médiatiques in Montréal: Sarah Boutin and Sophie Aubry. Our hope is that artists like these exploring and developing a recherche-création approach, will soon be included in JAR.

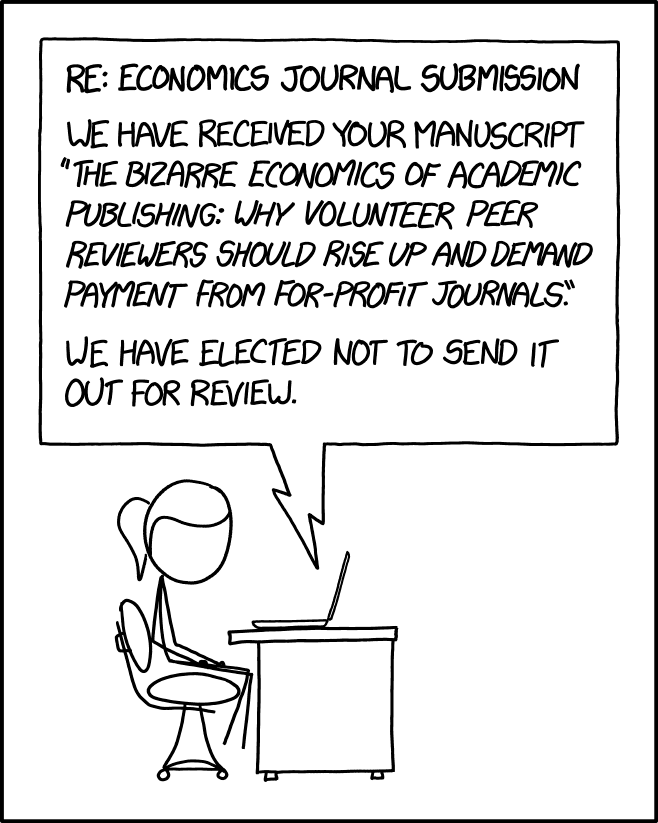

JAR’s peer review process is extremely thorough, and my own submission to JAR in 2015 received more valuable critical feedback than any of the 30 or so other peer reviewed articles I have published. However, the JAR workflow does seem to fall between scientific norms and the editorial approaches of publishing in professional journals in the arts.

We on the Editorial Board review submissions, and there is a very low bar for something going out to peer review. Julian finds appropriate reviewers with support of the board and peer reviewer responses are eventually received and discussed, resulting in either an ACCEPT, a REWORK, or a RESUBMIT. A Lead Editor from the board then works with the authors to address the concerns of the reviewers.

Many JAR submissions are exciting and a pleasure to work with, but a problem arises when a submission goes to peer review, gets lukewarm approval for publication with revisions, and no-one on the Editorial Board wants to Lead Edit the submission, because we are all unpaid on the board and overworked in our day jobs, and then it falls to the Michael as Editor in Chief or Barnaby as Managing Editor to edit, which can become a massive load. The larger issue here is that the peer-review process recommends publication of works which we do not have collective editorial enthusiasm for, or sometimes we don’t have the expertise to turn the submission into something exciting for our readers.

Recently, we are discussing whether we can address this by having a Lead Editor from the Board volunteer from the beginning to see an exposition through to completion, in advance of the peer review process. From my background in magazine publishing, the idea that one would begin a publishing process without editorial confidence in high quality result for readers is strange. I will spare you Michael’s and my debates on Kantian aesthetics that are relevant. But we know that in academic publishing, authors are incentivised to generate outputs, even if no-one reads them. Through a scientific lens, editorial enthusiasm is seen as bias and something to be downplayed. But the way our process requires an unpaid board to provide midwifery labour to an exposition that no-one really enjoys as if it were a scientific journal does seem out of step with what animates artistic research in the first place.

I am of course not discounting at all the importance of peer review, its impact on the quality of outputs or the diverse expertise it brings. I just raise this workflow question as an example of how, 10 years into the JAR experiment, sedimented habits of administration can determine the aesthetic output of the publishing process, and how difficult it is to adapt an organisational model to new understandings of “what works or doesn’t work” that we collectively discover and debate among the board.

Hi,

My speech is related to accessibility, which refers to the ability of an object to be used by as many users as possible. This notion has changed. While different cognitive or physiological conditions were purely seen as individual impairments that required medical treatments, we are now mostly perceiving them as relying on interactions that impacts the way they are lived, thus requiring an active removal of social barriers, and a fostering of different abilities. Besides, we are also recognizing that access difficulties also depend on global and national digital divides, because they imply that access to the Internet might rely on devices with a low-speed connection or with little screens, such as in mobiles or tablets.

In the case of JAR as a digital-sensorial environment, accessibility issues have mainly to do with its heavy reliance on visuality, sonority, and textuality, and also on expositionality, understood as a rich articulation between them through different kinds of media.

If JAR has still not developed all its accessibility potential, we are trying to improve it through technological and social solutions. In technological terms, the Research Catalogue allows navigators to automatically translate visual or sound languages into writings or readings. And, recently, the RC team has created a new block editor, added to existing ones, that allows easier ways to view, read and listen expositions in small devices, thanks to its responsive design capacities.

In social terms, improving accessibility will require the collaboration of JAR’s contributors. For instance, they might accompany their objects with written descriptions; or explore the block editor to make their expositions, along with or instead of the graphical editor. All of this, in a voluntary manner, because it implies some trade-offs that must be evaluated in each case. And, as to JAR, we might also explore different ways of communicating what we do through new media and social platforms.

Those evolutions will surely impact the ways in which we think and do artistic research through JAR, and expositionality might be affected especially in its spatial dimension. But I think that we all agree that unprecedented findings in esthetical, poetical and epistemical concerns might follow.

Thank you.

[The above video formed the backdrop to my contribution. In it, I described our development over the past ten years from my point of view. When initially we experimentally tried to establish the format of expositions for academic journals, the more the paradigm became established, the more we engaged with the repercussions. For instance, naively, in retrospect, we did not sufficiently problematize the exclusive use of English, nor the difficulty of doing justice to, at times, highly specific submissions. As the video says towards the end: If expositions are quasi singular events, what are the modes in which we relate to them, as makers, as authors, as reviewers, as editors, as readers?]