Juniper Fuse

two microtonal prepared pianos + two percussion + soprano saxophone

Musicians: Lotte Anker, Matt Choboter, Simon Toldam, Peter Bruun, Matias Seibæk

Fire

emerging human consciousness.

The mediator of this fire, the juniper twigs give light.

The flame of early human imagination

and creativity.

Psychic wombs,

caves yield art of prehistoric vistas.

For within these caves

hoping for primordial re-convene.

Juniper fuse is inspired by prehistoric cave wall imagery. There's a specified interest in the upper-palaeolithic art found in the Dordogne region of Southern France. A vital connection point into early human imagination and creativity, caves can be embodied as psychic wombs where one attempts to reach back in time and explore the archetypal subconscious.

Regarding mental health, poet, Clayton Eshleman reminds us of the need for our “deep mind” or subconscious mind. “For it is in the deep mind that wilderness and the unconsciousness become one, and in some half-understood but very profound way, our relation to the outer ecologies seems conditioned by our inner ecologies.” (11)

The ensemble, at its core, is essentially four distinct percussive entities.

Instrumentation

Microtonal prepared piano 1, Microtonal prepared piano 2 : nearly identical tuning + preparations

Classical percussion office: microtonal vibraphone, two taiko drums, oil can, orchestral bass drum, cymbals, crotales Extended drum kit: with rodo-toms, smalls gongs, singing bowls.

The Microtonal Vibraphone

I decided to re-tune a full set of vibraphone bars which would ultimately correspond to the microtonal prepared pianos. As previously discussed, the tuning system bridges the gap between just intonation and a Balinese Gamelan pentatonic scale called sedeng.

Sedeng Tuning Improvisations

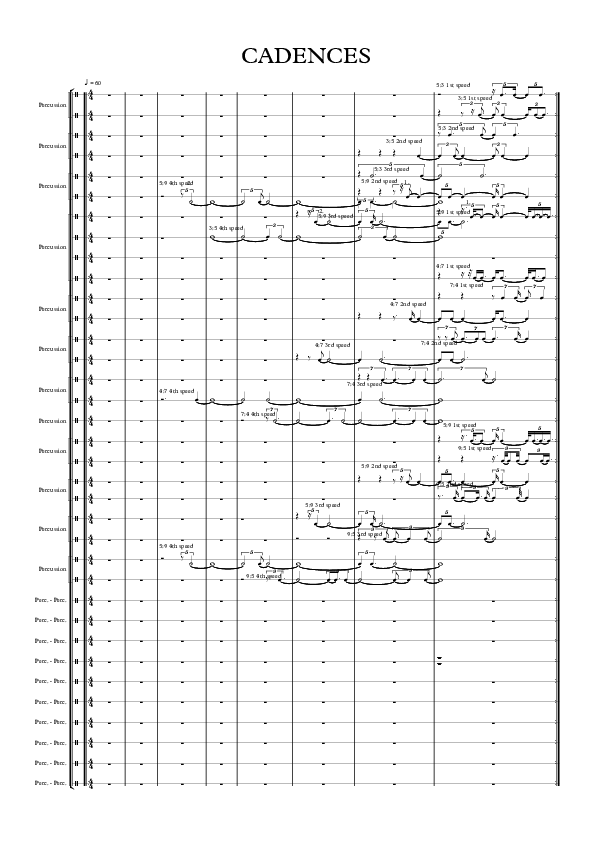

In the same way that a stone thrown into a lake creates interference waves, the collective cadences come together in larger rhythmic cycles that allow the ensemble to feel grounded in an “intuitive” vehicle for guided improvisation. In “out of womb” we experience this abstractly, through a 12-bar blues form.

The complex composite rhythm, between group members, generates rich interference patterns that would be extremely difficult to work with as an ensemble if it weren’t for a recognizable formal structure. In the recording, I’ve opted for a reduced orchestration of two percussion and soprano saxophone. There is no outward pulse and thus the musicians rely on each other for orientation within the repeating 12-bar cycle.

In terms of cadence functionality, one can observe a slow release of tension in the first half of the 12-bar form, and a build-up of tension in the second half. In this piece, the composite interference rhythm is palindromic as it reads the same forwards or backwards.

Approaches to rhythmic counterpoint: Poetic vs pulse-based conceptions

“An advanced musician may or may not wish to be consciously attentive to structure, but in any event will strive for a flexibility that enables changing from one kind of listening to another easily. Being able to shift and re-shift the foci of one’s perceptions is one of the experienced musicians best rewards”. Michael Tenzer, Gamelan Gong Kebyar pg. 22 (2000)

“In general, this music is more interested in navigating collective internal pulses, and spouting sound onto a blank canvas of moment-to-moment group listening”. (Matt Choboter, journal entry 2022)

I conceptualize and embody rhythmic counterpoint as composite interference fields. Each ensemble member is a cadential voice (patterns of stress and release) that converges and diverges with the surrounding layers. In this landscape one can find moments of full ensemble unison, partial ensemble unison and varying degrees of divergence with one another.

In rehearsing many of the pieces, there was a question of how to navigate the intricate counterpoints. In one extreme, an audible pulse could guide and orientate the ensemble. In the other extreme, pulse could be removed, relying only on internal pulse as well as formal markers. In this latter sense, a closer group listening was required where constant micro-adjustments might take place depending on the surrounding layers that each performer would react to. In this case, a kind of poeticism was achieved with a more qualitative and embodied movement of collective rhythm. Whereas in the pulse-based conception the result would tend to be more quantitative and mechanistic, in the same way that the second-hand on the clock marches fourth in accuracy and precision. Ultimately we’ve opted for a more poetic realization of this music. Often, we do use fragments of pulse in conveying groove and solidifying distinct polyrhythms. But, in general, this music is more interested in navigating collective internal pulses, and spouting sound onto a blank canvas of moment-to-moment group listening. The collective counterpoints become increasingly intuitive with more repetition. Rhythmic phrases and overall forms can be stretched and contracted as the unfolding of events becomes familiarized.

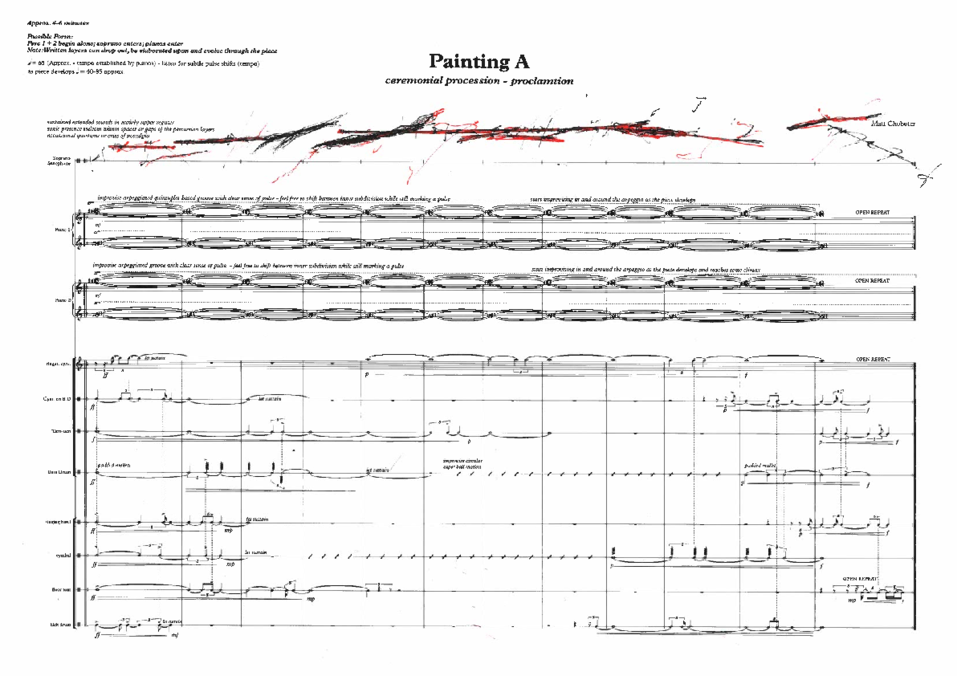

In Painting B, one can hear the realization of this intuitive and poetic rhythmic counterpoint.

Limiting my area of interest to the basics of vibraphone tuning - what are known as the 1st (fundamental) and 2nd transversal modes of vibration - I tuned approximately 17 bars by ear using a digital modelling (pianoteq) of the tuning system. I was intrigued by the future possibilities of tuning specific harmonics, whereby clear multi-phonics and chords might emerge. By emphasizing specific harmonics, the “perceived” fundamental might be obscured or erased all together. This process involves being able to map out the various transversal waves and their respective nodes (zero amplitude) and antinodes (maximum amplitude) that extend over the length of the vibraphone bar. It also opened an internal conversation regarding harmonicity versus inharmonicity and how metallic bars could be transformed, quite radically, into gong-like inharmonic sound projectors. I would like to further explore the inharmonic tuning of vibraphone bars and stretch their sounds beyond a conventional recognition.

Composing for this ensemble

Paintings have been used, mainly for my own purposes, to reflect upon macro-form intentions and overall themes. I’ve used paintings by my grandfather, Don Choboter, to abstract upon the theme of palaeolithic cave paintings and how they may relate to liminality from a more objective perspective. Palaeolithic cave art, from say the Dordogne region in Southern France, offers potential insights into the early early “human” psyche and its movement between consciousness and the subconscious. Looking into the future, I expect this project to become increasingly linked to liminal visual communication, whether within the ensemble or from without (the audience perception).

When writing for these instruments, I imagined a jungle of undifferentiated sounds. Undifferentiated in the sense of losing perception of where sounds might be taking place and who might be making them. It was important that all the percussion-based sounds work in strong combination with the microtonal prepared pianos. I took into consideration the macro frequency spectrums existing between all instruments. A great deal of focus was centred around timbral combinations and the awareness of emergent sound palettes based on a variety of instrumentation scenarios. Working with both a classical percussionist and improvising percussionist opened doors towards unique conversations about group aesthetics. Working with classical percussionist, Matias Seibæk, opened up extended sound possibilities, a chance to write for microtonal vibraphone and a general interest towards notational intricacy. Working with Peter Bruun opened new improvisational pathways whereby rhythmic poeticism could be explored. Below, I explore this rhythmic poeticism and how it relates to the underlying rhythmic principles in question.

“In general, this music is more interested in navigating collective internal pulses, and spouting sound onto a blank canvas of moment-to-moment group listening”. (Matt Choboter, journal entry 2022)

Collective rhythmics as a playground for extended minds

Rhythmic counterpoint is somehow akin to psycho-physical interference fields. Each ensemble member is a wave-field that converges and diverges within a larger collective field. Drawing from the ideas of physicist, David Bohm, the layers are enfolded (implicate) and unfolded (explicate). There is always a hidden potential whether or not it becomes explicit through sound.

Borrowing from Karnatik (South Indian Classical) rhythmic practice, we harness what are know as mukthi or mora patterns that form larger cadences. These cadences can be imagined as tension to release, or release to tension movements based on the number three.

They were conceptualized in larger rhythmic cycles, often relating to symmetrical or recognizable macro forms as to allow the musicians to feel grounded in an “intuitive” vehicle for improvisation.

Thus the performers were and are allowed to navigate between the intricate compositions as well as free improvisations.

Soprano saxophone was a late addition to the ensemble. It was in response to my desire for limited sectional or momentary use of heightened affect and unexpected changes in timbre and texture. I had several conversations with Lotte Anker relating to how we might achieve this. The examples I drew from include: the microtonal bagpipes used in Bulgarian folk music and how they often enter abruptly and for only short periods, taking the music and accompanying dance to a frenzied state; the suling (flute) that can enter unexpectedly and for relatively short periods of time within Balinese and Javanese Gamelan music; the way Wayne Shorter climaxes compositions within the context of his new quartet (with Danilo Perez, John Patitucci and Brian Blade). The first two examples were more relevant stylistically, since I wanted Lotte to aim for timbral gestures relating to extended playing techniques.