“Of course the laws of the natural function of our ear are, as it were, the building stones with which the edifice of our musical system has been erected, and the necessity of accurately understanding the nature of these materials in order to understand the construction of the edifice itself, has been clearly shewn. But just as people with differently directed tastes can erect extremely different kinds of buildings with the same stones, so also the history of music shews us that the same properties of the human ear could serve as the foundation of very different musical systems.

Hermann Helmholtz, On the Senstations of Tone (1877)

The microtonal prepared piano

i. Tuning

“The grease-filled corners of friction planes find meaning in “my” work - the inherent tensions of every scale of experience can be translated into the materials of music, namely an encompassing tuning constellation” (Choboter journal entry, 2022)

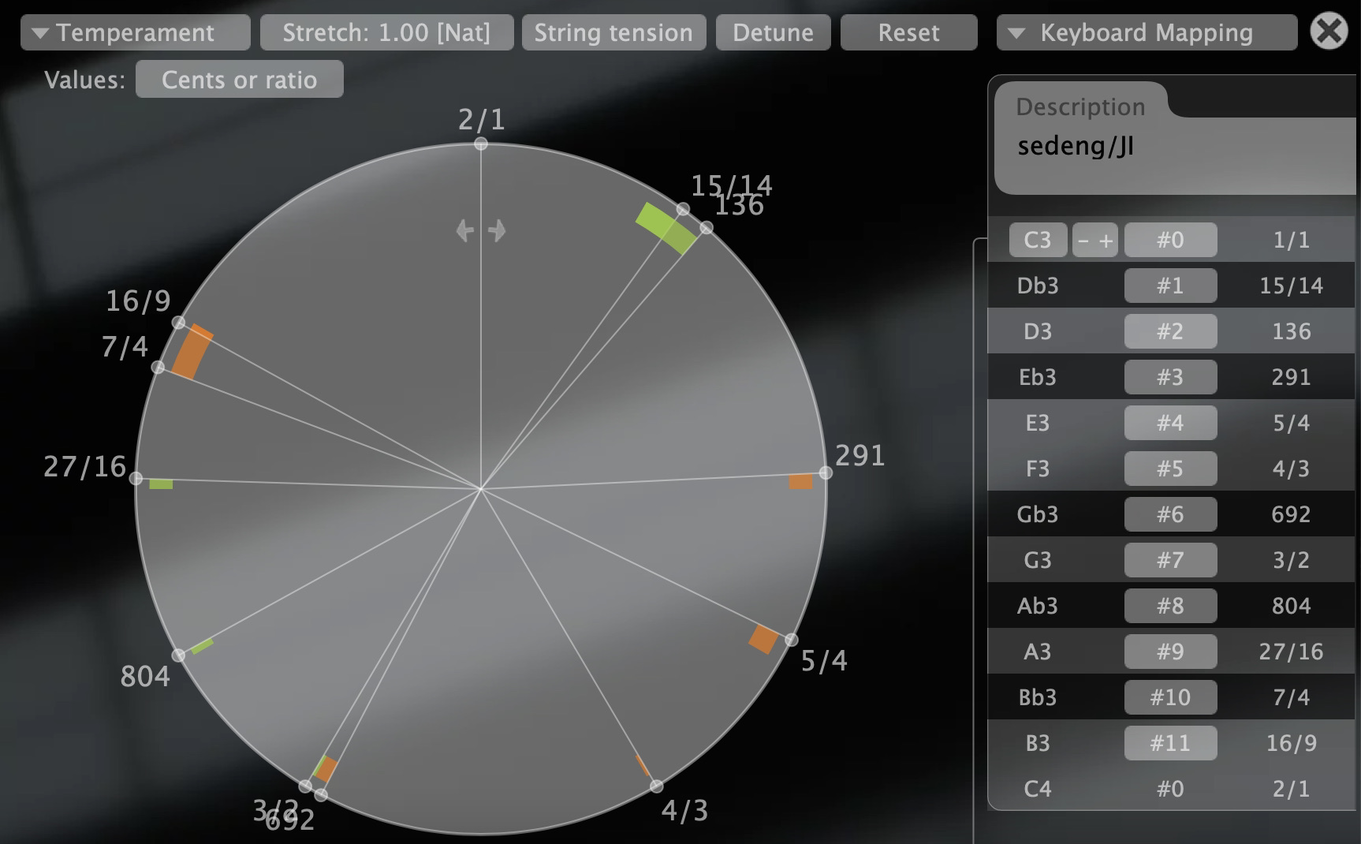

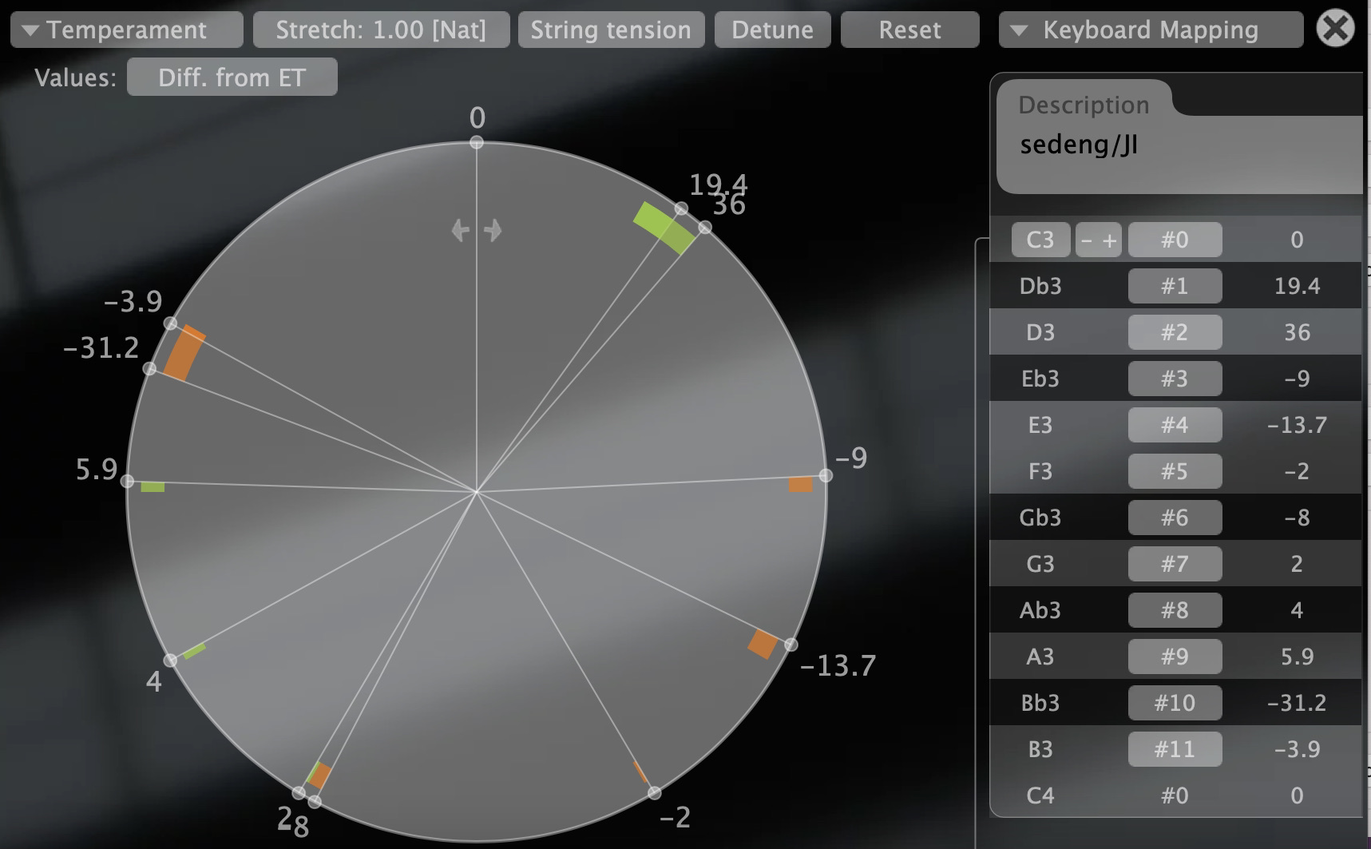

My tuning system confronts friction points between “harmonicity” and “inharmonicity”. In this context, harmonicity relates to Just Intonation and inharmonicity relates to a Balinese Gamelan pentatonic mode, called sedeng-pelog (a five note subset of the seven-note mode pelog composed of medium-sized microtonal intervals). I’m interested in how these seemingly juxtaposed systems of tuning organization can co-exist.

Using an octave repeating orientation with C as the fundamental, the following audio files give a sense of the two tuning constellations. It should be noted that the pentatonic scale along with the perfect ratios 3/2, 4/3, 5/4 and 7/4 serve as a kind of bedrock.

Balinese Gamelan Pelog-Sedeng Just Intonation

Pentatonic configurations have, in general, a non-hierarchical functionality which offers stability. The just perfect fifth (3/2) and just perfect fourth (4/3) offer another form of stability - a tonic to dominant to sub-dominant relationship. The distance between the just major 3rd (5/4) and the septimal minor 7th (7/4) create what is know as the septimal tritone, or can be thought of as the “purest” or “simplest” just tritone. It was important for me to investigate these primary harmonic qualities of western music from a strict just intonation perspective using the smallest or “simplest” ratios as possible. Then I could reflect on how these intervals expressed themselves in an “out of tune” 12 equal division temperament.

When the pelog-sedeng pentatonic subset is combined with these just intervals we are confronted with juxtaposed systems. One constellation offers a floating oriental non-hierarchy while the other, signs of a western functional harmony in pure harmonic form. Together, they offer a unique palette of colour and, an all together, different mode of orientation. I use the word “mode” since “C” tends to, or can easily become a gravitational point.

Choosing the remaining intervals, or colour pigments, was largely intuitive and based in direct experimentation and improvisation. I chose the justly-intonated intervals - 15/14, 27/16 and 16/9 to compliment, blend and most importantly create specified beatings and timbral effects.

When combining the aforementioned five-pitch (pentatonic) constellation with the seven-pitch (just interval) palette one can find interesting emergent properties.

One might notice three areas or axis’ of beatings. These exist between C#-D, F#-G, and A#-B. Each beating relationship is different and they range from 10 cents (1/10th of a semitone) to 27 cents (just over 1/8th of a semitone). The closer the intervals, the slower the beating, the further they are the faster they become. My inspiration for investigating beatings comes from the Balinese Gamelan practice of ombak - referred to as pengisep (lower tone or sucker) and pengenbung (higher tone or receiver) by local Balinese musicians - whereby “metallophones are tuned in close pairs for creating acoustic beating or "shimmering effects"(10).

Relating to the keyboard layout

The tuning system purposely breaks down the strict keyboard layout dichotomy between the 5 black keys (pentatonic) and the seven white keys (heptatonic). The just intervals and Balinese pentatonic are distributed across and beyond any black or white key demarcations. As an improviser, this has been especially important in avoiding clichés, recognizable or habitual shapes, patterns and vocabulary. In the future, I aim to do away completely with this black and white visual dichotomy and work with a new conceptual framework for the keyboard.

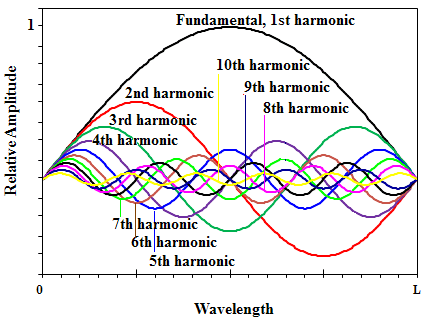

Placing the magnets on the strings of the piano, I’ve relied on my ears in finding the different nodes (zero amplitude) and antinodes (maximum amplitude) of various wave forms. This could relate to either a fundamental wave or the partial, or harmonic wave forms.

This entails that, by placing a preparation on a string, one can sonically access various wave forms that exist along the string. One could, for instance, focus on distorting the fundamental, or shape the sound quality of specific partials found in the harmonic series. The lower limit partials (especially the first 8 partials above the fundamental) tend to sing outwards and most prominently the lower one journeys into the lower frequency spectrum.

Placing a preparation (object) on a strings node will create minimum resonance while placement on an antinode will generally give greatest resonance. There is a delicate unpredictability in finding the resonance points. The foreign objects (preparations) bring their own physical makeup and thus we have two meeting entities towards one, or several produced sounds. As a composer and improviser, my interest lies in finding the “right” balance between harmonicity and inharmonicity for a given preparation, or sound entity. There is no hierarchy in terms of resonant sounds being “good” and non resonant sounds being less desired. In some cases, It is more aesthetically preferable to place a preparation directly on a node, and thus opt for a more deadened sound quality.

Positioning of magnets and metallic preparations

Although an intuitive process, I’ve been curious to reflect on the underlying acoustical phenomena. Each string on the piano, when excited, consists of a fundamental pitch (or wave) and many partial tones (wave forms that relate to the fundamental).

But why magnets? Why preparations?

Evoking liminality and the aesthetics of disorientation, ambiguity and illusion

Magnets can disorientate by confusing one’s perception of what the true string fundamental is. Depending on the preparation’s size, shape, weight, the strings fundamental could, for instance, modulate pitch, stay the same, or change timbral identity - clouded by new partials of varying intensities. In the latter case, we encounter what we may call a multi-phonic.

Multi-phonics are the acoustical phenomena of more than one pitch sounding at the same time. Multi-phonics open up the liminalities of pitch and tone. Preparations can create multi-phonics by empowering partials in inharmonic properties to emerge as perceived sound. It may be the case that certain partials completely overshadow an expected fundamental pitch. It may also be the case that the fundamental pitch ceases to sonically exist, which can occur especially if the una corda pedal is utilized. The piano, now conceived more as an ensemble of instruments, can now trespass beyond expected pitch linearities, where up-down, left-right orientations dissolve into a liminal jungle of irregularity.

My observations would indicate that preparations tend to carry the tuning into further disorientation, ambiguity and can create acoustical illusions for the ear. For me, magnets and metallic preparations relate to a South East Asian timbral perspective. I’m interested in evoking the shimmeringly disorientating qualities found in gamelan ensembles of Bali. I’m Deeply fascinated by ways of communicating liminality and Balinese sound worlds evoke this state of mind by focusing on instrumental inharmonicities. One may hear this, for instance, between the gongs, kempur, tromping, reyong and in various combinations.

But to mess with the tuning, why really?

“It could be a matter of confronting dualities. One could create understanding of the surrounding universe through mathematical or platonic rationalizations and idealizations. One could also seek this understanding through direct, embodied experience with nature. In the latter, one could direct attention to the present moment, to open oneself - to one’s greatest extent - to the plethora of perceptual channels and potentials that must, somehow, exist." (journal entry, 2021)

For me it’s about celebrating the friction between dualities, but also recognizing the potential for wholeness. The grease-filled corners of friction planes find meaning in “my” work - the inherent tensions of every scale of experience can be translated into the materials of music, namely an encompassing tuning constellation.

For it is in Just Intonation that we find this mathematical or platonic striving and in Balinese Gamelan that we, most tangibly, find embodiment.” (Choboter Journal entry, 2022)

The tampura in South Indian classical music not only provides a hypnotic drone function, but also conveys a rich timbral layer of sympathetic vibrations. In my microtonal prepared piano, tones that are closely tuned together - beating axis’ - evoke a transformed tampura. These axis’ or pillars are gravitational valleys for improvisations and compositions. I use a thin ring magnet, placed before the hammers, to evoke their quality.

The tuning system when combined with ring magnet preparations is a colliding duality which brings about friction points, or three distinct beating areas. The beating areas can freely dialogue with both the non-hierarchical sedeng pentatonic and the more hierarchic heptatonic just intonations. These friction points, or beatings, create a third structural element towards the process of composing.

Reflections

“Small paradigm shifts” in how I play my instrument and compose.

The new tuning and preparations have changed the way I interact with the piano. The tuning offers a much wider range of musical intervals. The intervals do not conform to an equal temperament and are thus microtonal. It’s challenged my habitual practice as a pianist in several ways. Firstly, I’ve had to explore new harmonic and melodic vocabulary, patterns, shapes and dismantle taken-for-granted principles. Principles like up and down are rendered meaningless when, for instance, a large mass of metal is attached to the resonating strings. In this particular instance, the fundamental frequency can be transposed down several octaves or perhaps a partial is coloured to such a degree that It loses its perceived pitch locality. Therefor the instrument loses its conventional sense of pitch chronology and becomes non-linear. Another area of interest involves the lightness versus heaviness of physical touch when pressing the keys. Each key has a specific sweet spot resonance in terms of how heavy or light it should be depressed. This is because of the delicate metallic preparations and the resulting multi-phonics that can be achieved with the right sense of physical touch. The matter can become problematic when combining two or more sounds simultaneously. For this reason I have almost completely avoided triads or larger chords as they have a tendency to collide with one another/cancel the resonances of each tone and oversaturate the overall sound canvas. Relating the piano, at least conceptually, to a modified Gamelan orchestra with timbral constituents, I avoid harmonic or melodic hierarchies and instead focus on amassing new sets of colour combinations on the sound canvas (whether composed or improvised). At this stage my habitual playing patterns have broken down along with conventional linearities.

The microtonal prepared piano opens the possibility for thinking beyond a set dogma or theoretical system. It allows me to distantly evoke both a western functional harmony and a characteristic Balinese tonality while transforming both through collision, obscuration, transformation, emergent interference patterns. To metaphorically visualize this, one may imagine two stones thrown in a lake and thereby create two separate wave patterns that, through meeting, create a new integrated wave pattern.

Together, the tuning and preparations hopefully synergize and inform each other along the winding paths of my personal and collective psyche.

ii. Preparations

A prepared piano can be described as having its sounds altered by various objects placed on, or within the resonating strings. In my case, I’ve chosen to work with metallic preparations and almost exclusively, magnets of various sizes, shape and weight. These include cones, spheres, squares, cylinders, magnet towers, rings, and nearly microscopic magnetic shards for subtle sympathetic vibrations. I’ve also been working with screws, bolts, bells attached to puddy, horse hair, rounded metallic bowls and more.