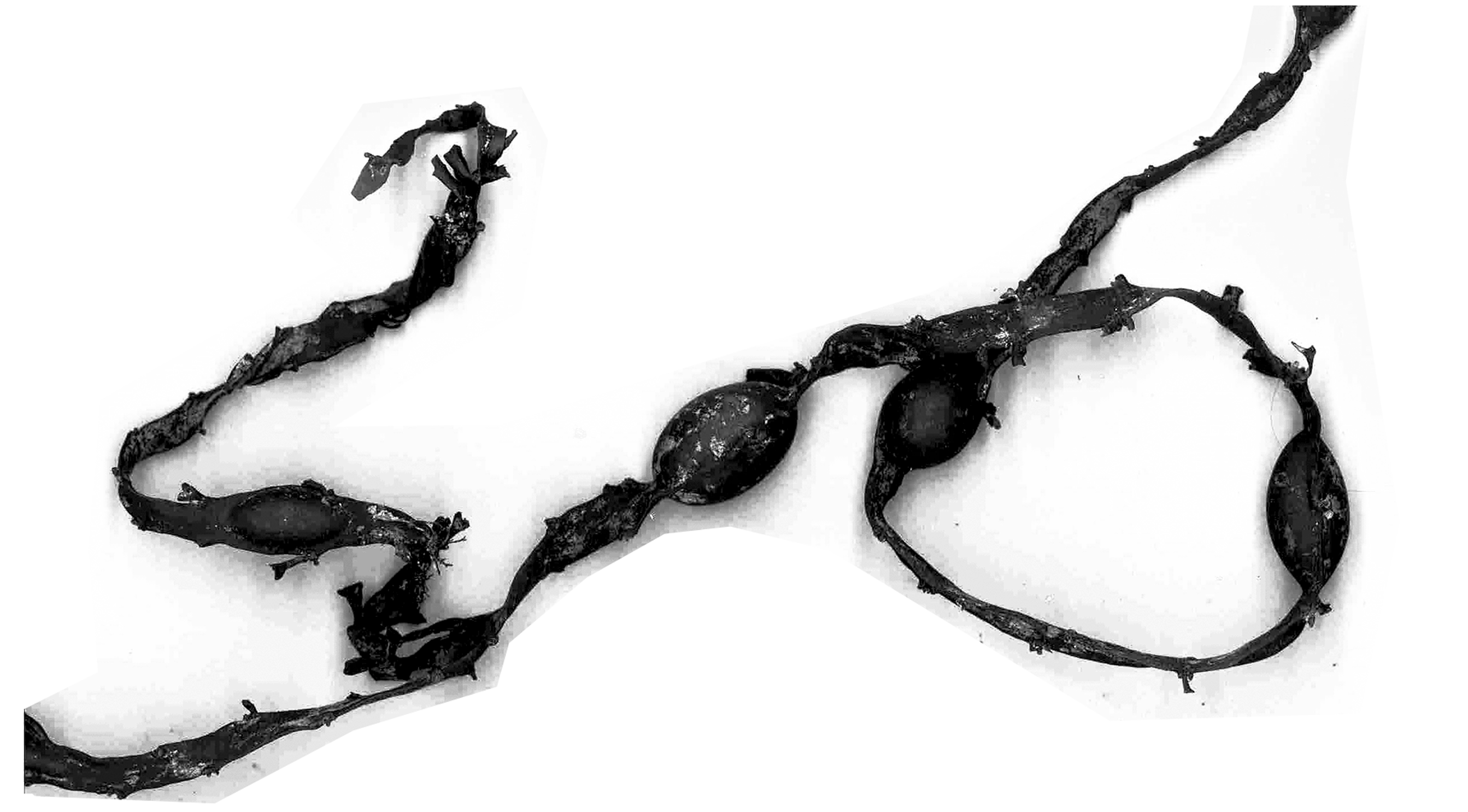

Notice, that many of the things around you consist of various elements that together compose one entity. A combination of glass, a wooden frame and some nails can be called a window. While the glass itself contains such elements as, for example, calcium carbonate, soda ash, and sand melted together at a very high temperature. Try to count: how many objects participate in the creation of the container object that you call your room?

Your alarm?

Your own body?

Searching for a Soul of Things is an attempt to raise the question on how we can have a dialogue with these entities, who “do not look like us […] have no eyes, no mouth, no ears but […] act all the same”[2]?

[2] LATOUR, B.; Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory; Oxford University Press, USA; 2007; p. 44

We are used to living within the realms of literal properties, systems and divisions. We are used to distinguishing animate and inanimate, useful and meaningless. But the window you know is different from the window I know, as well as your reality differs from mine. In a way, “all of the objects we experience are merely fictions: simplified models of the far more complex objects that continue to exist when I turn my head away from them, not to mention when I sleep or die.”[1]

[1] HARMAN, G.; Object-Oriented Ontology: A New Theory of Everything. (Pelican books, 2018), p. 34

To embark on this search let’s acknowledge that although the agency of non-human objects is different than ours, it has its own way of the shaping of this world. “Humanity and nonhumanity have always performed an intricate dance with each other. There was never a time when human agency was anything other than an interfolding network of humanity and nonhumanity”[3].

All kinds of matters, including ourselves, are combinations of collaborating elements and forces that act together via assemblages. An electrical circuit or an ecosystem are examples of co-operating bodies that exchange services with each other and we can project this concept onto our daily lives. For example, a washing machine helps to keep our clothes clean but we are also required to maintain it through costs electricity, water and washing powder.

Processes of co-operation are happening inertly, but perhaps by fostering our sensitivity towards them, we can consider an act of cooperating or care in itself as a form of dialogue. And furthermore, an awareness of these processes can be reflected in our daily behavior, blurring conventional hierarchies between human and nonhuman, and making the notion of an environment more playful.

[3] BENNET, J.; Vibrant Matter. A Political Ecology of Things; Duke University Press Durham and London 2010; p. 31