In his particular aesthetic approach, Frahm flirts with the notion of imperfection. His aim is not to make virtuoso music without making any mistakes. Flirting with ideas of imperfection in itself is nothing new, but the way Frahm handles imperfection seems distinct.

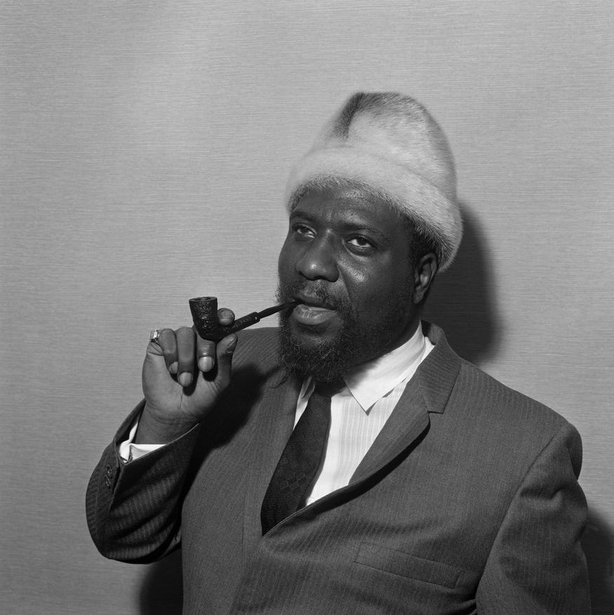

Thelonious Monk, for instance, “went after a radically different aesthetic, reminding listeners that it was he (…) who took full responsibility for the apparent ‘wrong’ notes, smudged intervals, and ‘accidents’ that (…) turned out to be right and deliberate after all” (Parakilas, p.305). The kind of imperfection Frahm is aiming at is different from Monk’s imperfect style of playing. Frahm does not deliberately hit dissonant tones, but allows for unintended imperfection to happen, thereby rendering the notion of imperfection powerless. His aesthetic approach permits unintended occurrences to carry aesthetic value in and of themselves, whereas Monk’s imperfect style of playing is nevertheless intended and therefore befitting the idea of the virtuoso player. Nevertheles, in Frahm’s approach not every accident is a happy accident, as became clear during one of his concerts:

Frahm started playing the organ, which was MIDI-fied and was controlled through a keyboard that was situated among a variety of other keyboards. A tape-delay machine was connected to the organ. After having played a number of tones, Frahm started to create layers of sounds by looping. At some point he could not get the loop as he wanted and the music seemed to lose its momentum. Frahm, took up the microphone, holding it as if he wanted to say something, while he was fiddling with the machine with his remaining hand. After a couple of seconds, he placed the microphone back in its stand, without having said anything and he continued making music, apparently satisfied with the layers of sound he created in the end. (Author’s fieldnotes)

Although not intended, these moments may enhance the suggestion of spontaneity and induce sympathy from the audience. But they also serve another function, as Frahm explains:

Well, of course it doesn’t work every single night, but I try to be as conscious, open and positive about each possible accident that can arise. Because when you get into certain patterns and you do things a certain way, you get kind of deaf and blind – accidents happen and you just freak out; you want it your way instead of thinking and reflecting about all the untapped possibilities. Personally, that often leads to something new, and that’s where I really learn something – on stage. I’ve learned so much about music ever since I started playing live shows. (Harding, 2013)

In Frahm’s approach, accidents, whether aesthetically valuable in themselves or not, are necessary evils that prevent a player from becoming insusceptible to the value of accidents.

References

- Harding, M. O. (2013). Between the musical chairs.MUTEK. Retrieved from: http://www.mutek.org/en/magazine/571-between-the-musical-chairs

- Parakilas, J. (1999). Piano roles: three hundred years of life with the piano. Yale University Press.

- Do you want to know more about Nils Frahm's aesthetical approach?

- Or would you rather read something completely different perhaps about Bach or virtual pipe organs?