In my essay, I compare how the Pierre Palla Organ was originally constructed and played a part in the 1930s with how this instrument will be reconstructed in the 21st century. For the purposes of this presentation, the following only highlights some of the more insightful aspects of the current reconstruction of the Pierre Palla Organ – for more information on the original construction of the instrument, following this link.

The goal of the restoration of this theatre organ is to let the organ become once more part of a musical culture, and to spark the interest of young people. It is not a project about reconstructing an organ as authentically as possible, but is aimed at creating “a new culture structured around this instrument” (Den Dikken interview).

Perhaps the most interesting idea behind the reconstruction of this instrument is to also make the Pierre Palla Organ an instrument to be studied. This ties in with the idea that the organ can be an instrument of knowledge. Peters (2013) argues about church organs that these “have always been instruments of knowledge. These sometimes ancient instruments can be compared to coral reefs, containing the material, scientific, and artistic sediments of ages” (p. 88). This could also be said about the Pierre Palla Organ, as this instrument – and the processes involved in its reconstruction – can be used to educate young people about organ building in the past and in the present, and can also disclose something about the past rivalry from whence the organ originated.

In order to make the organ attractive as an instrument to practice on and to be studied by young people, there are going to be two major changes to the instrument. First of all, the relay technique is going to be altered. This has to do with the way the pressing of the key is transferred to the pipe. Second, there will be a MIDI exit and that offers opportunities for instance to play the organ without a musician. The idea for the reconstruction is thus that the parts creating the organ sound are authentic but the ways in which the sound is transported through the instrument are new. This kind of electronic interface, as Randall Harlow calls it “invites new genres of multi-instrumental or computer collaboration, as well as endless possibilities among new modalities of direct performance by agents removed from the organ keyboards. Advances in this kind of interfacing may hold the key for resurgence in the organ’s esteem among art music in the 21st century” (2011, p.40).

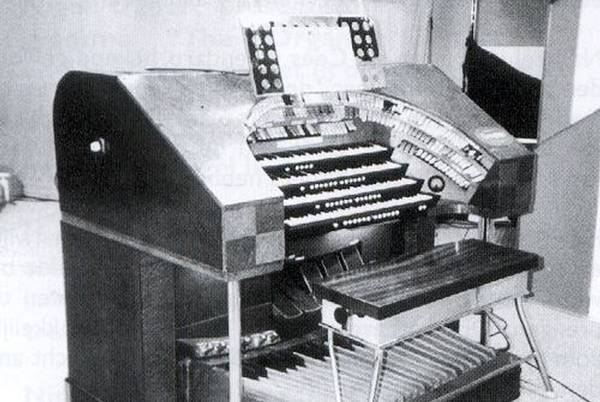

The Pierre Palla Organ, when completely restored, should therefore be seen as a hybrid organ. It is a normal pipe organ but it has unique sound effects and instruments contained within and can therefore be used in a variety of ways. It can play theatre organ music, but it might also be used to play classical music or church music. The building where the instrument will be placed is mainly a centre for classical musicians, and the question is: “What can we do with this popular instrument in a classical environment? Can an orchestra […] use this instrument as a classic organ?” (Den Dikken interview).

Robert Hope-Jones, the founder of the theatre organ, once argued that if the percussion instruments are not used, the theatre organ could function as a church organ (Doesburg 2013). The organ will thus be used in different ways compared to how it was used in the past, when it mainly played popular music. In the future situation the theatre organ will therefore be reconfigured in a way which makes it suitable to play theatre organ music, classical music and church music.

The section of my paper concerned with the restoration of the Pierre Palla Organ, all in all, attempts to show that this project is not about reviving an old theatre organ culture in the Netherlands. It is instead aimed at creating a new theatre organ culture and focused on trying to encourage young people to become part of this culture. The Pierre Palla Organ will be updated, modernised and will have more functions; it can be used in different ways compared to how the instrument was used in the past, and the digital aspects of the organ, it is hoped, should spark the interest of today’s youth.

References

- Doesburg, C.L. (1996). Orgels bij de omroep in Nederland. Naarden: Strengholt.

- Doesburg, C.L. (2013). “De Geschiedenis van het Pierre Palla Concertorgel.” In: Plan tot restauratie van het rijksmonument Pierre Palla Concertorgel en herbouw in het muziekcentrum van de omroep in Hilversum. Pp. 6-65.

- Harlow, R. (2011). Recent Organ Design Innovations and the 21st-century “Hyperorgan”.

- Peters, P.F. (2013). Research Organs as Experimental Systems: Constructivist Notions of Experimentation in Artistic Research. In M. Schwab (Ed.), Experimental Systems. Future Knowledge in Artistic Research (pp. 87-101). Leuven: Leuven University Press.

- Interview with Arie Den Dikken, May 6, 2015. MCO, Hilversum.

- Another type of organ you might be interested in is the pipe organ.

- Do you want to learn more about the consequences of instruments in musical spaces? Then click here.

- You can also learn more about the history of the Pierre Palla Organ or radio culture.