For the first time, “the orchestra was placed in front of the stage, having previously sat at the sides, in galleries, or behind the scenes” (Forsyth, 1985, p. 76). The area in front of the stage is known to be the first orchestra pit; however not sunken but on the same level as the audience, at the same time being separated by rail. Soon it had been recognized that by placing the orchestra in front of the stage, the sound of the orchestra was more brilliant and much clearer. Once public opera houses in Venice were commercially successful, the idea of public opera houses quickly spread to other cities, including the newly introduced orchestra pit (Forsyth, 1985).

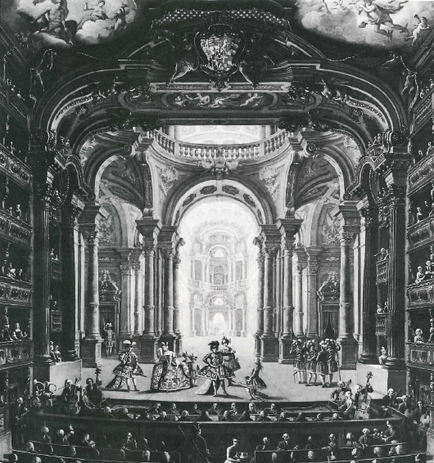

The idea of placing the orchestra in front of the stage in a pit was one of the ongoing and standardized features of Italian Baroque opera houses. In the Teatro Regio in Turin (1738-1740), for example, the orchestra also sat in front of the stage, but on two long tables. These required a certain seating order of the musicians for the whole orchestra to fit in the area. One row of musicians was thereby placed with the back to the stage, whereas the other was facing the stage and turning their backs to the audience. This seating order prevailed partly until the nineteenth century, as for example in the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden, London (Meyer, 1972). What was special about the orchestra pit in the Teatro Regio was the fact that the architect had installed a semi-cylindrical resonance chamber under the orchestra, which connected to the stage via acoustic tubes (Baumann, 2011). This was supposed to amplify and project the orchestra’s sound and was a common feature to many Italian theatres.

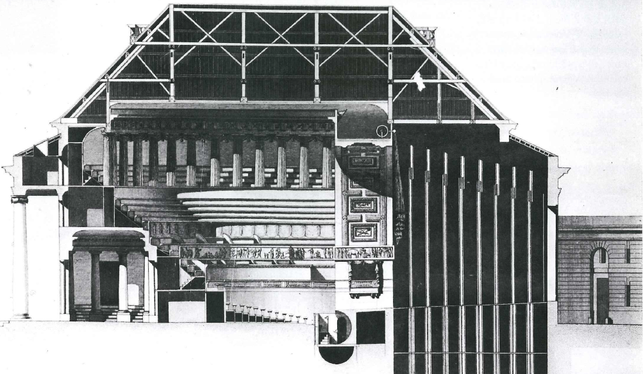

The first sunken orchestra pit was built only a bit later at the Theater at Besançon (1778-1784), France. The architect, Claude-Nicolas Ledoux, aimed at concealing the orchestra in order to increase the dramatic effect on the stage (Forsyth, 1985). The back wall of the pit was of a semi-cylindrical form, in order to act as a reflector. Strangely enough, in practice this element was an acoustic disadvantage, for the musicians experienced the music as disturbingly loud. It did not even have an effect on the audience because the concave wall directed the sound horizontally, in such a way that it could not even reach beyond the pit (Baumann, 2011).

References

-

Barron, M. (1994). Auditorium acoustics and architectural design. Spon Press.

-

Baumann, D. (2011). Music and Space: A systematic and historical investigation into the impact of architectural acoustics on performance practice followed by a study of Handel’s Messiah. Peter Lang AG, International Academic Publishers.

-

Forsyth, M. (1985). Buildings for Music: The Architect, the Musician, and the Listener from the Seventeenth Century to the Present Day. Cambridge: MIT Press.

-

Meyer, J. (1972). Akustik und musikalische Aufführungspraxis : Leitfaden für Akustiker, Tonmeister, Musiker, Instrumentenbauer und Architekten. Verlag Das Musikinstrument.