‘Three metamorphoses of the spirit I name for you: how the spirit becomes a camel, and the camel a lion, and finally the lion a child’ (Nietzsche, Z I:1, ‘The Three Metamorphoses’).

‘Drei Verwandlungen nenne ich euch des Geistes: wie der Geist zum Kameele wird, und zum Löwen das Kameel, und zum Kinde zuletzt der Löwe’ (Nietzsche, Z I, ‘Von den drei Verwandlungen’).

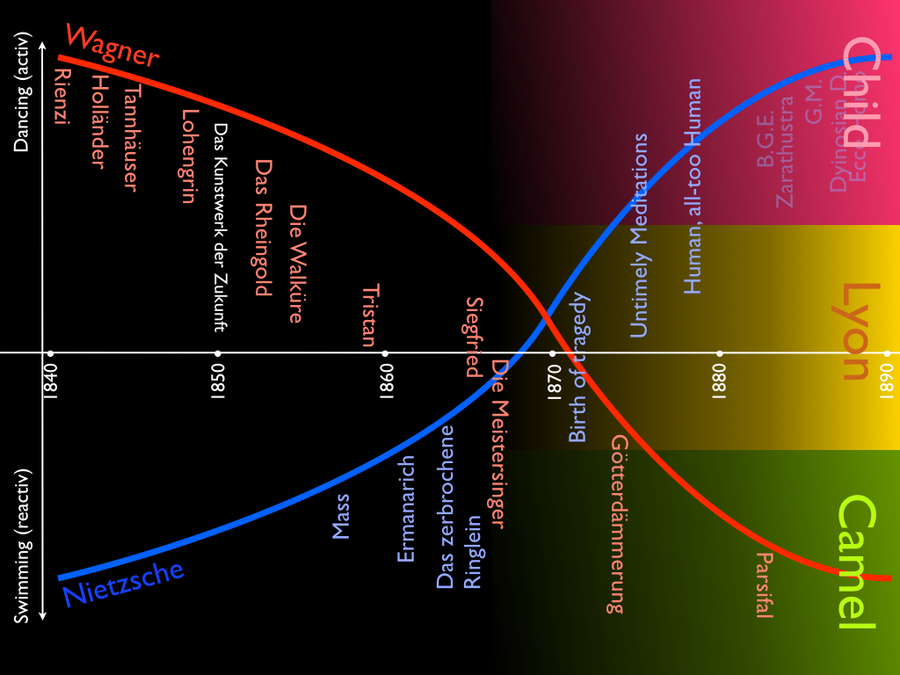

Our diagrammatic representation of the timelines of Wagner’s and Nietzsche’s works serve as a means to visualise Nietzsche’s inner path from the oppressive weight carried in works such as the Miserere and Ermanarich to the fragmentary and dissolved reiterations of his multiple ‘I’s’ in Ecce Homo and other texts from his last period. Concomitantly, one can think of Wagner’s trajectory as increasingly exposing a proto-religious horizon, culminating with Parsifal. Obviously, we are not addressing here the purely aesthetic qualities of Wagner’s last works, whose qualities (and groundbreaking musical potential) passed unnoticed by Nietzsche, who was focused on (and disappointed by) their reactionary narratives. On the other hand, and precisely at this level of musical narratives and dramaturgy, Nietzsche’s Ermanarich, the unfinished Mass, or the fragmentary Christmas Oratorio share a similar reactive character with Wagner’s Ring and Parsifal (in Nietzsche’s interpretation of these works). In this sense, what Nietzsche most dislikes in Wagner might well be those aspects of Wagner that he feels latently, but deeply present in himself, elements of which his music is a testimony and which he constantly tries to overcome:

‘I am just as much a child of my age as Wagner, which is to say a decadent. It is just that I have understood this, I have resisted it’ (Nietzsche, WA, Preface).

‘Ich bin so gut wie Wagner das Kind dieser Zeit, will sagen ein décadent: nur dass ich das begriff, nur dass ich mich dagegen wehrte’ (Nietzsche, WA, Vorwort)