Missa (Miserere), 1860

Music: Friedrich Nietzsche

The Orpheus Singers; Peter Schubert, conductor.

Recorded 1996, Albany Music, CD#178.

‘On Ascension Day, I went to the city church and heard the sublime chorus from the Messiah: the Hallelujah! I felt as if I ought to join in the singing; it really seemed to me like the jubilant song of angels in the midst of whose loud singing Jesus Christ ascends heavenward. I immediately made the decision in earnest to compose something similar. Right after church, I thus set to work and, in a childlike way, delighted over the sound of every new chord that I struck. But while I never stopped working on it over the years, I still gained a great deal from it, since I learned to read music a little better through the acquisition of tone-structure. […] I thus conceived an inextinguishable hatred for all modern music and everything that was not classical. Mozart and Hayden, Schubert and Mendelssohn, Beethoven and Bach – these alone are the pillars on which only German music and I rest’ (Nietzsche 2012: 15; translation adjusted).

Tristan und Isolde, Isoldes Liebestod (excerpt), 1857–59

Text/Music: Richard Wagner

Kirsten Flagstad, Philharmonia Orchestra, Wilhelm Furtwängler; Covent Garden, London, 1952

Hans von Bülow, letter to Nietzsche, 24 July 1872:

Your Manfred-Meditation is the most extreme form of far-fetched extravagance, the most dreadful and anti-musical that I have seen on music paper in a long time. […] Should you really have a passionate urge to express yourself in musical language, it is imperative to learn its basic elements: a fantasy stumbling in an indulgent reminiscence of Wagnerian sounds is no basis for production. […] Should you, valued professor, have meant your deviation into the field of composition to be taken seriously, which I am still doubting – then at least compose vocal music – and let the word take the wheel of the barque carrying you on the wild sea of sounds. (Benders and Ottermann 2000: 273, trans. Michael Schwab)

Nietzsche’s reaction, letter to Erwin Rhode, 02 August 1872:

Regarding my last composition, which I played for you in Bayreuth, I finally and truthfully learned my lesson; in its honesty, Bülow’s letter is invaluable to me, read it, make fun of me and trust me that I myself got into such a dread that I have since not been able to touch a piano. (Nietzsche 1986: vol. 4, letter 249, p. 43, trans. Michael Schwab)

Parsifal, Prelude (excerpt), 1878–82

Text/Music: Richard Wagner

Violin: Sayoko Mundy; Electronics: Juan Parra Cancino

Parsifal, Act 3 (excerpt, final section), 1882

Text/Music: Richard Wagner

Chor und Orchester der Bayreuther Festspiele, Hans Knappertsbusch; Bayreuther Festspiele, 1962.

Piano Sonata in D Minor, op. 31, no. 2 (‘The Tempest’), 3rd movement (Allegretto), 1801/02

Music: Ludwig van Beethoven

Daniel Barenboim, piano, live recording, Berlin, 2012.

[Audio extracted from the open-source weblink: http://youtu.be/jtDAbP3UxPY]

Unless otherwise indicated all recordings were performed by Paulo de Assis (piano) and Valentin Gloor (voice). Piano: Bechstein 1899. Recorded 7 July 2015, Orpheus Institute (Concert Hall), Ghent. Recording master: Juan Parra C.

a ME21 | Orpheus Institute, Ghent (BE)

b University of Applied Arts Vienna (AT)

c Zurich University of the Arts (CH)

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme for research, technological development, and demonstration under grant agreement number 313419.

The pianist, now much closer to the audience, plays the piano part to the monodrama Das zerbrochene Ringlein. The spoken voice is projected through the loudspeakers and the face of the narrator is frontally and/or laterally projected onto the screens. There are two screens between which the piano has been moved.

A contact microphone, placed inside the piano, captures its sounds and progressively transforms them, adding new layers and increasingly taking over acoustically. At some point the live electronics will be so massive and loud that the pianist leaves the stage. Ultimately the distorted sound will be unbearable to the audience leading to a sudden stop. End of the performance.

As the audience enters the concert hall Nietzsche’s choral music is softly, almost imperceptibly diffused through the loudspeakers. At the official starting time of the performance, electronic manipulations of the piano recording of Nietzsche’s Melodiefragment prepare the piano entry. Progressively moving down from extremely high frequencies to the sounding frequencies of Melodiefragment, they lead to the live performance of this short melodic fragment, composed when Nietzsche was ten years old.

Nietzsche’s musical works were composed almost exclusively during his adolescence, in particular between 1854 (Melodiefragment for piano solo) and 1863 (Ermanarich for two pianos), from his tenth to his nineteenth year of age. Until 1874 he kept composing other epigonic pieces, including Manfred-Meditation (for piano four hands, 1872), Gebet an das Leben (1874, with a text by Lou Andreas-Salomé added 1882), and Hymnus auf die Freundschaft (1874).

Nietzsche’s pre-recorded Miserere is diffused through four loudspeakers, submerging the audience in a seldom-heard piece of music. On screen, the title, date of composition, and composer’s name are laconically projected.

A web search is made in real time and projected on screen and through the loudspeakers, making audible and visible today with different means and media what affected the young Nietzsche in 1858.

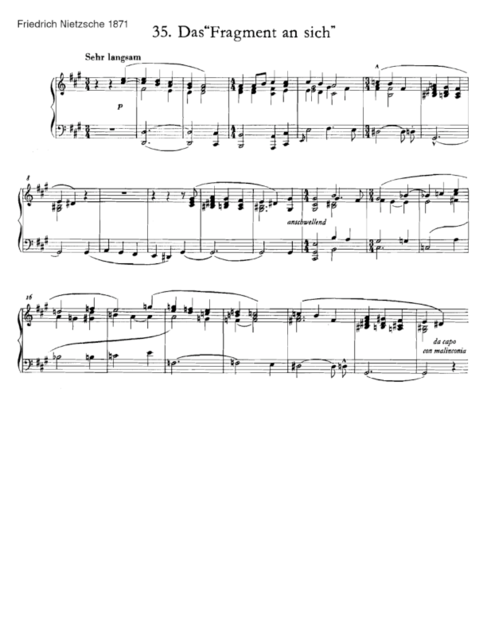

Yet, already in 1862, the eighteen-year-old Nietzsche starts laughing … ‘So, won’t you laugh?’ seems to reveal (even if in a moderate, constrained, and almost melancholic way) a germinal predisposition against too much seriousness, against the weight of norms, religion, historicity, and other values of the time. So lach doch mal and Das ‘Fragment an sich’ remain marginal productions of the young Nietzsche, whose full musical concentration was devoted to pieces like the projected Mass, the symphonic poem Ermanarich, or the Manfred-Meditation for piano four hands. However, they contain a germ of rebellion and might be, therefore, relevant to understand Nietzsche’s later developments.

In 1886, under the new title of The Birth of Tragedy; or, Hellenism and Pessimism, Nietzsche reissued his first successful book, The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music from 1872. For the new publication, he wrote an important prefatory essay, ‘Versuch einer Selbstkritik’ (‘An Attempt at Self-Criticism’), in which he tried to reposition his discourse, which had substantially changed since 1872. By 1886, Nietzsche had significantly moved away from his former sources of thought and inspiration – namely Schopenhauer and Wagner.

In addition to the previous use of pre-recorded music, a new element is exposed onstage: a pre-recorded face reading an excerpt from the ‘Attempt at Self-Criticism’. This might raise questions: Who is onstage? What is being mediated? Where is Nietzsche?

The young Nietzsche was a profound admirer of some of Wagner’s works, above all Tristan und Isolde, which he discovered in a piano reduction for four hands made by Hans von Bülow. Nietzsche had played it by 1860, at the age of sixteen.

We reach the middle of the performance. Nietzsche’s most substantial musical project – the planned opera on Ermanarich – is played at the piano while a pre-recorded narrator accompanies the pianist with Nietzsche’s dramaturgical comments on the music.

All lights off. In the darkness the pianist moves the piano further toward the next position (Das zerbrochene Ringlein). A neutral, pre-recorded radiophonic voice, haltingly reads fragments from Bülow’s letter and from Nietzsche’s reaction.

Intermittently, fragments from the just-played Ermanarich are played back – extremely softly and almost inaudibly.

All lights on. Onstage everything is frozen. Nothing moves. Brechtian Verfremdungseffekt (distancing effect). Hold on as long as possible!

Fragments from the final scene of Parsifal are heard and the word ‘Parsifal’ moves slowly and intermittently in a direct path at the bottom of the two screens — passing from one to the other and disappearing in darkness.

Live piano and pre-recorded voice present selected excerpts/fragments from Gebet an das Leben (1882), one of Nietzsche’s last attempts to rescue musical ideas from 1874, in this case using a recently composed poem by Lou Andreas-Salomé from 1882.

According to the medical reports of the mental asylum of Jena (see Janz 1976: 18), where Nietzsche was hospitalised between 18 January and 24 March 1890 (immediately after his mental breakdown in Carignano Square in Turin), Nietzsche played by heart Beethoven’s sonata ‘op. 31’. Despite that there are three sonatas in Beethoven’s op. 31, we take the risk to assume that it was op. 31, no. 2, the famous ‘Tempest Sonata’. Its third movement, with its obsessive, almost manic refrain and its continuous unbroken repetition of sixteenth notes seems to be a perfect musical suggestion of Nietzsche’s Ewiger Wiederkehr.

Das ‘Fragment an sich’ (1871) has no end: there are no double or final bar markings as Nietzsche explicitly indicates ‘da capo’, implying eternal repetition. This is exactly what we suggest: the pianist plays and replays the piece for ‘as long as possible’. Each reiteration subtracts more and more elements of the musical material.

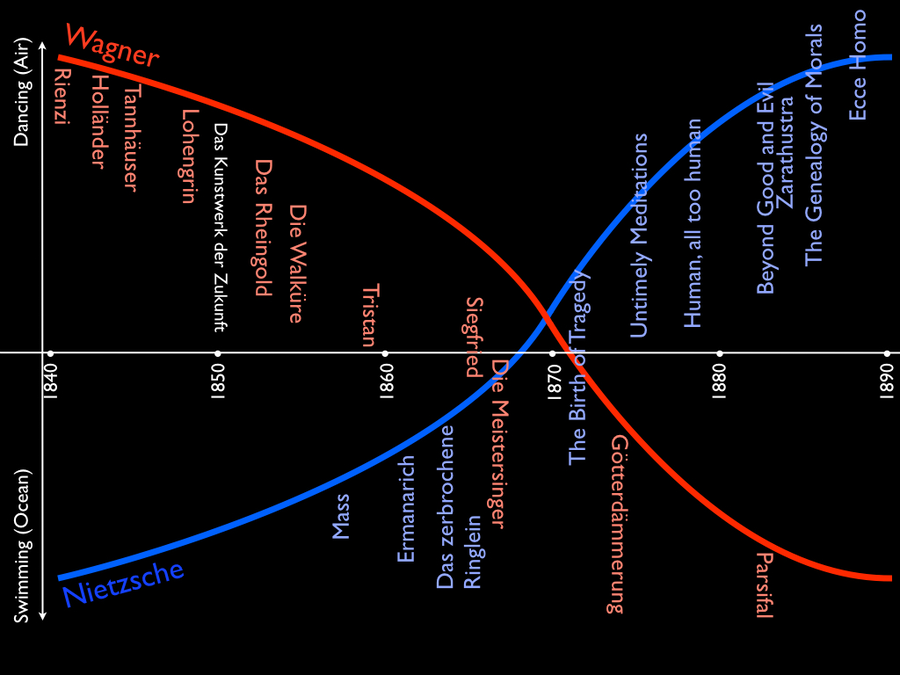

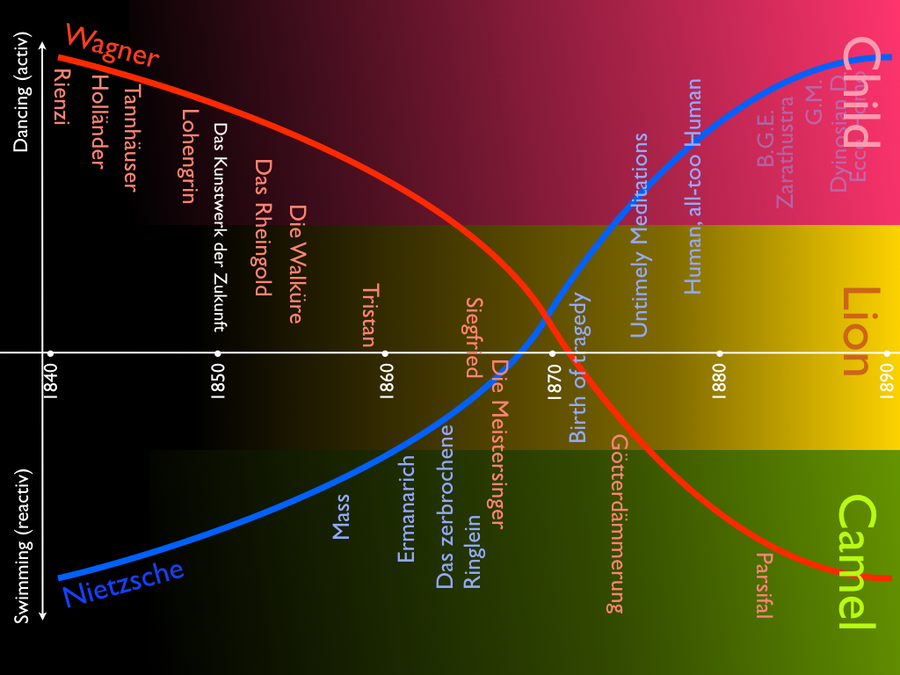

One can identify a double movement on the part of Nietzsche toward Wagner: a moment of attraction, and, later on, of repulsion. The phase of attraction develops between 1860 and 1872, while the estrangement begins in 1874, a time when Nietzsche was working on his Untimely Meditations. In a letter to Georges Morris Brandes dated 19 February 1888, Nietzsche writes that ‘the Untimely Meditations, deserve the most detailed attention to understand my development’ (Breazeale 1997: xxv).

With the Untimely Meditations Nietzsche voices his thinking about the untimely, about the chasm with his own time, and inaugurates a new relationship with the idea of ‘historicity’ itself, in philosophy as well as in science and art. From a biographical perspective this is also the moment when Nietzsche ultimately abandons any musical intention of being a composer.

‘– A final cry of Ermanarich and the first part of the drama is concluded, everything silent, deserted, awaiting redemption [wartend auf Erlösung].’

Nietzsche 5 : The Fragmentary is part of a broader artistic research project on the music of Nietzsche entitled Nietzsche N, which is a satellite project of MusicExperiment21 [ME21] (PI: Paulo de Assis, Orpheus Institute Ghent, BE). Nietzsche N is being realised by Paulo de Assis, Michael Schwab, Valentin Gloor, Lucia D’Errico, and Juan Parra C.

Nietzsche1 was an in-progress presentation on 30 April 2014 to the fellows of the Orpheus Research Centre in Music [ORCiM] in Ghent, BE.

Nietzsche2 — Das ‘Fragment an sich’ was presented as part of the III Congreso Internacional de Epistemología y Metodología ‘Nietzsche y la Ciencia’ on 9 May 2014 at the Biblioteca Nacional, Buenos Aires, AR.

Nietzsche 3: Radical Epistemology (Michael Schwab) and Nietzsche 4: Fragments of a Musical Discourse (Paulo de Assis). Proceedings of the III Congreso Internacional de Epistemología y Metodología; forthcoming.

Nietzsche 5 : The Fragmentary was prepared specifically for submission to Ruukku and represents a development from Nietzsche1 and Nietzsche2, which did not discuss the fragmentary. Most recordings were specifically realised for this submission.

Nietzsche #6: The Weight of Music was presented at SCORES: PHILOSOPHY ON STAGE #4 at the Tanzquartier Vienna, 28 November 2015. This conference is part of the research project Artist Philosophers: Philosophy as Arts-Based Research (Arno Böhler, University for Applied Arts Vienna, AT).

Across the different presentations of Nietzsche, the structural role of chronology has been debated. In Nietzsche 5 : The Fragmentary, as in most of the other parts, the middle of the programme – bracketed by two motives from Wagner, one looking forward, the other backward – stands for Nietzsche’s crossing from music making to philosophy making circa 1872 and also for his embrace of the fragmentary. While this order is structurally important, at the same time, later developments shape and reshape earlier ones, and vice versa. For example, the 1886 ‘Versuch einer Selbstkritik’ became part of Die Geburt der Tragödie from 1871 as if it always had been untimely avant la lettre. When, for example, we move Das ‘Fragment an sich’ (1871) to the very end of the programme, we also interfere with the chronological order as if it suggested not only the concept of the ‘eternal return’ but also a mode of terminating taken as it were (almost) from the beginning.

While Nietzsche the philosopher – with his provocative laughter – was able to build a new image of thought, Nietzsche the composer – with his proto-religious deference – essentially matched the clichés and values of his own time. According to Curt Paul Janz, the editor of Nietzsche’s musical works (Nietzsche 1976), for the young Nietzsche the creative artist acted as a ‘medium’: something, some unknown entity composed through him, and the artist remained separated from his creation, at the point of feeling a relative estrangement from it (ibid.: 331), as though it were not ‘his own’ creation. In this sense, Nietzsche the composer is submersed in a Schopenhauerian ocean, with his notions of artistic ‘genius’ and ‘intuition’ as important landmarks. Overall, Nietzsche’s music reveals deeply archaic roots, faithful reverberations of his own time – a very timely music, zeitgemäß.

‘Whoever reads Nietzsche without laughing, and laughing heartily and often and sometimes hysterically, is almost not reading Nietzsche at all’ (Deleuze 2004: 257).

Significantly, Nietzsche’s attachment to the arts is related first to the arts of music and poetry. Music is not only a prominent presence in all stages of his philosophical path: Nietzsche himself composed a substantial number of musical pieces and, when talking about music, he usually argued with the insight and knowledge of a music practitioner and maker more than that of a pure musical theoretician. One fundamental aspect of Nietzsche 5 : The Fragmentary is precisely to focus attention on Nietzsche-the-composer. When thinking about music, Nietzsche thinks not only about the music of other composers (such as Wagner, Schumann, or Bizet) – his discourse is impinged by his own interior reflection on his own musical instincts and his own musical works. The relevance of Nietzsche’s personal biography can hardly be eluded in this particular matter. For it was in the years 1872 to 1874 – the period of the Unzeitgemässen, of the distanciation from Wagner, of Hans von Bülow’s harsh criticism – that Nietzsche stopped composing music to embrace a philosophical path totally. Whereas the musical works of his youth carried a transcendentalising, ‘profound’, and emotionally overloaded pathos, his musical criticism after 1874 developed a growing hatred precisely to music where Nietzsche saw, heard, or felt exactly these characteristics.

‘All things considered, I could not have endured my youth without Wagner’s music. For I was condemned to Germans. If one wants to be free of an unbearable burden, one needs hashish. Well then, I needed Wagner. Wagner is the counter-poison to everything German par excellence – poison, I do not dispute it … From the moment there was a piano score of Tristan – my compliments, Herr von Bülow! – , I was Wagnerian. The earlier works of Wagner I deemed as beneath me – still too common, too ‘German’ … But even to this day I search for a work of equally dangerous fascination, of equally sweet and shuddering infinity as Tristan is – I search in vain in all the arts. All the grotesqueries of Leonardo da Vinci lose their charm at the first note of Tristan. This work is absolutely Wagner’s non plus ultra; he recuperated from it with the Meistersinger and the Ring. To become healthier – that is a step backward for a nature like Wagner’s’ (Nietzsche, EH, II.6).

In spring 1861 Nietzsche composed the first version of Ermanarich, a symphonic poem for two pianos, following the model of Liszt’s Dante Symphony. A year later, in 1862, he composed a version for solo piano, and in November 1863 he devoted himself to intense research on the Hungarian legend of Ermanarich, the Ostrogoth king, consulting libraries and writing a sixty-page text on the subject. Finally, in 1865, at the age of twenty-one, he prepared a libretto for an opera based on that story (see Janz 1976: 330–32).

According to Curt Paul Janz, Nietzsche approached the subject at first in a purely sensorial way, neglecting historical accuracy as much as the literary form of the narration. In his autobiographical observations of 1862, Nietzsche wrote the following:

In the last months of 1874, Nietzsche made a thorough revision of his own musical works. On 2 January 1875, he wrote to Malwida von Meysenbug:

It seems to me incredibly peculiar the force with which the immutable character of a person unveils in and through his music. What a young boy expresses in music, that is the language of his deep essence [Grundwesen] to such an extent that the old cannot wish to change it. Therefore, when the same boy becomes old, he will encounter in his own compositions the manifestation of the fundamental essence of his complete naturalness. (See Schlechta 1976: viii)

Surprisingly, this was written in 1875 – that is, after his first successful philosophical works (such as The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music, 1872, second edition 1874), and the second Untimely Meditation (1874). That at this stage Nietzsche considered his own (highly ‘reactive’) musical compositions to be a reflection of ‘the language of his deep essence’ might indicate the kind of underlying décadence Nietzsche identified in himself (the same one he attached to Wagner), and, therefore, the need to overcome himself to become someone completely different – as he did through his philosophical writings. Nietzsche the philosopher emerges (also, or partially) in (negative) tension to Nietzsche the composer.

We enter the fragmentary in Nietzsche through two sections of Maurice Blanchot’s The Infinite Conversation: ‘Nietzsche and Fragmentary Writing’ and ‘The Athenaeum’. While in the latter section Blanchot states that ‘Romanticism inaugurates an epoch’ based on the central role of the fragment (Blanchot 1993: 356–59), it is first of all through Nietzsche that the fragmentary is developed, in particular as demand. Walter Benjamin, in his seminal The Concept of Criticism in German Romanticism, likewise highlights the importance of the fragment in early Romanticism but focuses on the notion of ‘critique’, despite quoting Friedrich Schlegel in saying that ‘every fragment is critical’ (jedes Fragment sei kritisch) and ‘critical, and in fragments would be tautological’ (kritsch und Fragemente wäre tautologisch) (Benjamin [1996] 2004: 142; German original: Benjamin 2003: 51–52). A discussion in its own terms of the beginning of that epoch of the fragmentary, in which Blanchot places Nietzsche, can first be found in Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe and Jean-Luc Nancy’s The Literary Absolute (1988), which traces the fragmentary as exigency at the heart of early German Romanticism. Lacoue-Labarthe and Nancy explicitly depart from Benjamin’s focus on Fichte; implied with this departure, so we suggest, is a turn toward the fragmentary and, in terms of emphasis, away from reflection.

‘One cannot read Nietzsche without being swept up with him by the pure movement of the research,’ says Blanchot (1993: 145). To Blanchot, the ‘rigorous knowledge’ (ibid.) that Nietzsche represents would not be thinkable without the fragmentary, which we suggest takes over shortly after Nietzsche gave up his ambitions as a composer – a new artistic position now realised in writing.

Blanchot helps us see that this new position is a demand and not a choice first recognised as a form of expression breaking all stylistic confines. Nietzsche, in fact, invents a language, which, in turn, also makes him Nietzsche. Blanchot calls this language ‘fragmentary writing’.

Note first that the fragmentary is not set up as a descriptor of the world (e.g., ‘the world is fragmentary’) but as a challenge to practice. In fact, what we think the world is is arbitrary while the movement that makes us adopt this or that belief is not. Blanchot (1993) expresses this in two ways: first, the fragmentary ‘does not have its content as its meaning’ (ibid.: 152) and, second, ‘thought as the affirmation of chance’ (ibid.: 154).

In the fragmentary, ‘thought … is plural’ (ibid.). Having harnessed plurality, fragmentary thought (which is always also fragmentary action) ‘is also this lighthearted movement that tears itself from the origin’ (ibid.: 156). Being able to tear oneself from the origin – and survive and remain affirmative – is the becoming-origin that can be nothing other than a process, which, along with Nietzsche, we might call ‘life’, this time though as knowledge. The fragmentary facilitates this strange and counterintuitive reversal of origin: from a ground needed in something else – always somewhere else – as an excuse for true assertions, to an origin with no fixture where truth becomes a self-relation. ‘Fragmentation is this god [the god that is fragmented] himself, that which has no relation whatsoever with a center and cannot be referred to an origin’ (ibid.: 157).

Lacoue-Labarthe and Nancy link the fragmentary to the concept of ‘work’. The notion of ‘work’ refers first to a work of art. However, increasingly through the course of the first chapter of The Literary Absolute, such a substantive notion of ‘work’ is taken apart until at the end the seemingly paradoxical notion of ‘unworking’ is proposed as the modus operandi of a work of art (Lacoue-Labarthe and Nancy 1988: 57). This complication of the work of art (and, ultimately, also that of the subject) is in large part due to its understanding as a fragment, as proposed by the early Romantics.

One important aspect that makes discussing the fragment so difficult is its own fragmentary status within early Romantic thinking. Lacoue-Labarthe and Nancy (1988: 41–42) suggest that – under conditions of the fragmentary – it is no coincidence that the central notion of the ‘fragment’ remains both underdefined and underused. A fragment, as Lacoue-Labarthe and Nancy (1988: 42) say, ‘involves an essential incompletion’ that disallows it to be put to rest. ‘In this sense, every fragment is a project: the fragment-project does not operate as a program or prospectus but as the immediate projection of what it nonetheless incompletes’ (ibid.: 43).

‘What does a philosopher demand of himself, first and last? To overcome his age, to become “timeless”. So what gives him his greatest challenge? Whatever marks him as a child of his age. Well then! I am just as much a child of my age as Wagner, which is to say a decadent: it is just that I have understood this, I have resisted it. The philosopher in me has resisted it’ (Nietzsche, WA, Preface).

‘Those who are truly contemporary, who truly belong to their time, are those who neither perfectly coincide with it nor adjust themselves to its demands. They are thus in this sense untimely [inattuale]. But precisely because of this condition, precisely through this disconnection and this anachronism, they are more capable than others of perceiving and grasping their own time’ (Agamben 2009: 40).

Agamben’s use of the word ‘untimely’ refers back to Nietzsche’s Untimely Meditations, in particular to the second, ‘Vom Nutzen und Nachteil der Historie für das Leben’ (‘On the Utility and Liability of History for Life’), dated February 1874. Nietzsche expresses his annoyance toward many of the most prominent features of the political, philosophical, and intellectual landscape of the European culture of his time. Daniel Breazeale notes that ‘it was with the Untimely Meditations that Nietzsche found the courage to say “No!” to his own time, to his own age, to his academic friends, and, evidently, to some very important parts of himself’ (Breazeale 1997: xv). To name one of these parts: his own music and musicality.

‘Lifetime [Aiōn] is a child at play, moving pieces in a game. Kingship belongs to the child’ (Heraclitus, Fragment XCIV [or B 52], as translated in Kahn 1979: 71).

In his lectures in Basel in 1873, Nietzsche analysed Heraclitus Fragment B 52 no less than six times and it is quoted seven times in his (posthumously published) Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks (1873). At the beginning of the seventh chapter, Nietzsche states:

In this world only play, play as artists and children engage in it, exhibits coming-to-be and passing away, structuring and destroying, without any moral additive, in forever equal innocence. And as children and artists play, so plays the ever-living fire. It constructs and destroys, all in innocence. Such is the game that the aeon plays with itself. Transforming itself into water and earth, it builds towers of sand like a child at the seashore, piles them up and tramples them down. From time to time it starts the game anew. (Nietzsche [1962] 1998: 62; our emphasis).

According to Günter Wohlfart (2010: 3–4), ‘This fragment [B 52], along with Nietzsche’s interpretation and translation of it into his own thought, can be seen as a decisive point of intersection for various lines which connect the early Nietzsche of the Basle years with the late and the “hardest” thought of eternal recurrence, the apex of Nietzsche’s philosophy of life. […] Nietzsche uses Heraclitus’ fragment B 52, to sketch his own “artist-metaphysics”. […] B 52 is the philosophical knot in which Nietzsche’s “artist-metaphysics” of life is tied together with his doctrine of eternal recurrence.’

The ‘Experimentation versus Interpretation: Exploring New Paths in Music Performance in the Twenty-First Century’ (MusicExperiment21, in short: ME21) is an artistic research programme funded by the European Research Council (Starting Grant nr 313419). It involves a group of artist-researchers studying and proposing transformations of concepts and practices in the musical performance of Western notated art music. ME21 attempts to found a new transdisciplinary practice of and discourse on how to relate to past musical objects, proposing a different and original model for musical performance – a model that takes into account older modes of performance (execution, Vortrag, interpretation, performance, a.o.) but which, crucially, is based upon ‘experimentation’.

Beyond ‘critical thinking’, ME21 advances ‘material thinking’ in and through the concrete making of music. Integrating material that goes beyond the score (such as sketches, texts, concepts, images, videos, new commissions) into performances, this project offers a broader contextualisation of the works within a transdisciplinary horizon. To achieve this, the project has a multidisciplinary structure, with specific research strands on artistic practice, musicology, philosophy, and epistemology, which generates a network of aesthetico-epistemic references that emerge at different professional stages, as well as in the context of leading international projects and music ensembles.

In Nietzsche #6: The Weight of Music (Vienna, Tanzquartier Wien, 28 November 2016) So lach doch mal (So, won’t you laugh?) was scattered more often throughout the performance, reappearing three times, while in previous performances (such as Nietzsche2: Das ‘Fragment an sich’, Buenos Aires, National Library, 9 May 2014) it was played only once. Its repetition has three reasons:

- It emphasises the moment of ‘laughter’ and ‘laughing’ in and for Nietzsche’s thought

- It enables the operator at the piano to generate differential repetitions

- The piece is liberated from its chronology and gains the function of dramaturgical ‘separator’, breaking potential stratifications of the materials

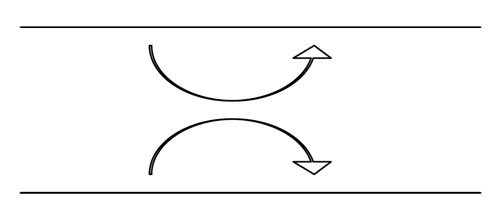

The performance diagram for Nietzsche #6: The Weight of Music, as it was performed at Tanzquartier Vienna, 28 November 2015. The red line shows the path of the piano during the one hour duration of the performance (punctual movements, from one piece to the next); the blue circle defines the area in which a dancer suggested two modes of relating to music, one of ‘dancing’, the other of ‘swimming’; the two bold black lines mark the two video projection screens.

The problematisation of ‘work’ is central to ME21 both with regard to the source materials for its case studies and the form of its outputs. Paulo de Assis has developed an approach to each ‘work’ that decomposes it into a set of ‘things’, which are extensive material objects (real things, existing in the real world) that are the result (sedimentation) of intensive processes and concrete actions (drafting, arranging, composing, editing, performing, etc.). On the one hand, we focus on a materialist approach based on innumerable physical objects (fragments); on the other hand, we stress that such materials ‘breathe’ and give notice of a fundamental creative activity, which must be re-enacted every time again and again. Therefore, even when we say, ‘this edition of a score!’, ‘that intensity of play!’, ‘this past performance!’, or ‘this philosophic commentary!’, we mean the particular and specific power, the intensity that radiates from that object (and not necessarily the object itself). All those ‘things’ (fragments) belong to a ‘manifold’ that makes up – at a given point in time – what we take a particular work to be. Each manifold exponentially grows the more work is invested.

Crucially, there is no ‘complete’ performance of all things simultaneously. When a work is performed, selected things (belonging to its manifold) are put into a functional relation in order to challenge the limits of a work, its potentiality, and its possible meaning(s). To Assis, although a work is performed, it is better to speak of an assemblage that is put onstage, an experiment that will or will not be recognisable as the work. If it is, we may ask: In this recognition, have we just experienced the work again, or have we gained a new insight into what the work can also be?

Nietzsche was not planned as the subject of a case study at the outset of ME21, since, at first, musical works with a strong canonical status were its concern. Nietzsche’s ultimately problematic compositions initially were simply a way to expand ME21 and to include the musical work of a philosopher relevant to ME21. However, much of what is written here or what has been developed for the other instances of Nietzsche N also represents an apparatus meant to allow us to find something in these compositions beyond, for example, Hans von Bülow’s devastating judgement.

With expositionality – the exposition of practice as research – Michael Schwab (e.g., 2011; 2012; Schwab and Borgdorff 2014) has developed a concept that responds to the uneasy relationship between presentation and representation in the context of artistic research. Structurally, expositionality can be compared to the will-to-power insofar as it also describes a differential, form-giving process as (artistic) form. However, in terms of its philosophical status, expositionality is not meant to explain what things are – not even ‘research’ – providing neither a metaphysical framework nor an ontology; rather, it is meant to give guidance to artistic researchers regarding the scope of what is epistemically possible, insofar as knowledge may be advanced together with and as result of an artistic engagement with the very conditions of knowledge. This bottom-up approach suggests epistemologies to come, projected within the expositional gesture. Expositions can thus work; that is, they can evidence knowledge without being grounded in pre-existing, complete, and transparent epistemologies. In fact, expositionality may be a necessary aspect of any historical epistemology, since, in situations of historical change, what just emerges can, by definition, not yet be established.

ME21 team meeting (brainstorm) for Nietzsche2, 10 December 2013, excerpts. Participants (from left to right): Valentin Gloor, Tiziano Manca, Bob Gilmore, Juan Parra, Paulo de Assis, Paolo Giudici, Michael Schwab.

Rasch#11 (excerpt on ‘Dancing and Swimming’), Paulo de Assis and ME21 Collective, Orpheus Festival 2014.

Snapshot from Nietzsche #6: The Weight of Music (dress rehearsal), Tanzquartier Wien, 28 November 2015. Paulo de Assis (piano).

It seems that in artistic research, we must problematise all names, including that of Friedrich Nietzsche. We not only encounter under the name of Nietzsche a set of materials from which we are historically if not geographically removed and which we could put into perspective and interpret; we have become the interpreters that we are also through Nietzsche since we are outside neither history nor culture. As we drag Nietzsche’s compositions into the light, we run the risk of suggesting a human (all too human) origin, when, in fact, all we want to propose is some form of (transhistorical) relationship from which various originators emerge, including ‘Friedrich Nietzsche’ and ourselves. When focusing on these relationships from which originators can emerge, it may be possible if not necessary that the person that emerges as ‘Friedrich Nietzsche’ is at odds with the person that he claimed to be, or with the various persons suggested by others after him. To us, the better question is, How does Nietzsche 5 : The Fragmentary add to and intensify various sets of materials, such as those known as Nietzsche, or, likewise, as Artistic Research?

When Nietzsche, in his ‘An Attempt at Self-Criticism’ (‘Versuch einer Selbstkritik’) from 1886, asks for an ‘artiste’s metaphysics’ (Artistenmetaphysik), he does so, first of all, not to suggest an artistic ground to all metaphysics, but – read in combination with the search for an ‘exceptional type of artist’ (Ausnahme-Art von Künstlern) – to advocate the need for a radical artistic position able to appropriate all possible concepts, including those of philosophy, without exception. That this move may also return ‘a philosophy’ is secondary; it is more relevant that it is an artist’s philosophy.

According to Helmut Heit, ‘also biographically, […] a principle problematisation of science was possible for Nietzsche only through a detour via art’ (Heit 2011: 10, our translation; dass eine grundlegende Problematisierung der Wissenschaft Nietzsche selbst nur durch den Umweg über die Kunst mö̧glich war.). This suggests that it is not so much a question of art versus science (which has to be understood according to the more general German term, Wissenschaft), but of a radicalisation of the regime of knowledge that for Nietzsche commenced with Socrates. This implies the questioning of Truth(s) on all levels, including those that keep art and science apart as well as science epistemically aloof. The ‘artists with some subsidiary capacity for analysis and retrospection’ (BT/GT, Attempt 2; Künstler mit dem Nebenhange analytischer und retrospektiver Fähigkeiten) are those that bring rationality not irrationality to science, which is, according to Heit (2011: 9–10), ‘the immanent consequence of an honest [redlich] use of rationality’.

Those artists of ‘a type you would have to go looking for, but one you would not really want to seek’ (BT/GT, Attempt 2, amended translation; nach denen man suchen muss und nicht einmal suchen möchte) are not just artists one would readily find under this label, including – in 1886 – Richard Wagner (Heit 2011: 5n4). Such ‘future’ artists are more projected than real – a necessary site necessarily left open.

It is such a relationship to growth and future that for Azade Seyhan puts Nietzsche in early-Romantic company. As she says, ‘Since art is always alerted to the non-conclusive nature of reality, it is redeemed by its self-reflexive and ironic sensibility, whereas reason and logic are trapped in what Nietzsche calls “metaphysical delusion” (metaphysischer Wahnsinn). The persistent irony and mobility in which Nietzsche invests art aligns his thought unmistakably with that of the early Romantics’ (Seyhan 1992: 138; source of Nietzsche quotation not identified). Lacoue-Labarthe and Nancy (1988: 148n25) concur when they say, ‘One sees all that Nietzsche could have taken from romanticism […]. But it is surely the theme of the philosopher-artist that is most fundamentally romantic in his work.’ Despite such overlaps, there are voices, such as Judith Norman’s, who believe that ‘Nietzsche does not belong to this historical lineage [the one that links early Romanticism with Heidegger and deconstruction]’ since 'the idea of an a priori transcendental ground is foreign to him' (Norman 2002: 519). With our focus on the fragmentary, we suggest that both positions are valid: the fragmentary, indeed, is an key early Romantic trope, but it is also a concept through which to facilitate a departure.

Assuming that credibility is given to Nietzsche’s science-critical stance, which requires the concept of the ‘artist’ to be mobilised, it may be that the biographic can no longer be sidelined as that that simply provides the ground for his philosophy – a ground that, consequently, can be interpretatively harvested. Rather, embracing the fragmentary, Nietzsche has to insist on himself against our interpretations, as affirmative as they might be, since ‘himself’ is an inconclusive material becoming, and as such a fragment. Crucially, however, Nietzsche's becoming-artist can also be put as a question of music: What mode of music can overcome its impending timeliness?

Western notated art music is one of humankind’s most highly coded forms of expression. The making of a musical score has been regarded for many centuries now – using Adorno’s terminology – as a reification, the turning of a process into a thing, the ‘freezing’ of a temporal moment of subjectivity (personal or collective). In Deleuzian terms one could think of extensive captures of intense processes that happen at the level of ‘desiring-production’. In many ways, musical coding and encoding go together with repression of desire, with taming primordial impulses and animal (vital) flows. In this sense, different kinds of music can and do afford different ‘regimes of knowledge’, from highly coded, essentially gregarious stratifications of musical entities (e.g., national anthems) to less coded manifestations (such as extemporisations and/or improvisations). Nietzsche saw in late Wagner a growing tendency toward repression of desire, or, what is the same, to a celebration of the socius, of desire understood as essentially gregarious in nature, desire as trained and disciplined to produce collectivities, desire as socialised by codification, by the attribution of (complex) meaning.

In opposition to this, Nietzsche discovers in Bizet’s Carmen another kind of sensuality, one full of gaiety and lightness: ‘its happiness is short, sudden, without reprieve’ (Nietzsche, WA, 231). Through Carmen, Nietzsche seems to glimpse a primordial biological, energetic, germinal, purely creative and vital world. A world without rituals and codes. Pure childhood. Aiōn. Heraclitus’ child, moving pieces on a board (cf. Heraclitus, Fragment XCIV [or B 52]).

Part of the development of artistic research must be the search for suitable epistemologies that do not contradict artistic practice. This is not to say that orthodox epistemologies may not be utilised or be of interest to artists; it only means that particular elements that seem to us essential to artistic practice must also matter epistemologically.

While questions such as whether artistic practice may count as research or what it may do to knowledge are still ongoing, a second longstanding transformation cuts across and confuses discussions: that of a principal turn away of academia from Bildung (education but also formation) as social duty to a market-driven model creating and selling knowledge. Since artistic research entered the scene at a crucial time (in Europe referred to as the Bologna Process or, more generally, globalisation) during the recent wave of transformations, which also affected the financial and institutional independence of art schools, ‘research’ has been treated by many not only as a concern internal to academia but also as a concept along which to bring art into line.

This is probably the case. However, despite this, can there not be a point at which artists may refuse to have things prescribed to them by others? What may happen to research if it is artistically appropriated? In particular, can an artistic challenge to simplistic notions of knowledge be mounted that is also valid for fields not considered ‘art’? And, also, can the decline of criticism, if not criticality, be responded to by switching from the aesthetic to the epistemic?

Nietzsche, in the second of his Untimely Meditations, diagnoses a ‘historical illness’ (historische Krankheit), which he describes thus: ‘Excess of history has attacked life’s plastic powers, it no longer knows how to employ the past as a nourishing food’ (UM/UB 2: section 10; note that in the translation we replaced ‘malady of history’ with ‘historical illness’ to highlight that history is also cause; Das Uebermass von Historie hat die plastische Kraft des Lebens angriffen, es versteht nicht mehr, sich der Vergangenheit wie einer kräftigen Nahrung zu bedienen). This illness expresses itself through a type of repetition in which identity is preserved rather than differentially produced, for example, as generation or growth. In terms of the later Nietzsche, this illness is nihilism and decline. This ‘historical illness’ can also be described in terms of ‘future’: while future is produced, it remains a repetition of the past. To Nietzsche, then, such ‘overdominating history’ is actually deeply ‘unhistorical’ (unhistorisch) (UM/UB 2: section 1). Martin Heidegger links nihilism to technology, whose history due to its unhistorical core completes itself (Vollendung) as ‘perpetual ending’ (Ver-endung) (Heidegger [1954] 1994: 67, note that in German ‘Verendung’ also denotes the [slow] dying of an animal on its own). (Incidentally, due to the lack of an end or historical containment, such ‘perpetual ending’, being totalising, cannot be fragmentary.)

‘Research’, seen from the dominant scientific angle, is very much implied in this issue. As the historian of science Hans-Jörg Rheinberger suggests quoting François Jacob, experimental set-ups are ‘machines for making the future’ (as quoted in, e.g., Rheinberger 1997: 28). However, while future knowledge is necessarily unpredictable, it is still conditioned by the kind of knowledge apparatus that Heidegger criticises and which to Nietzsche is lacking in plastic powers.

Art, science, and philosophy all create relationships to time and history. History takes place in Chronos, while art (if it deserves that name) is the movement from Chronos into Aiōn. Artistic artefacts are historical since they have a day of creation and are surrounded by particular contexts; they are ahistorical since they have to overcome their own historical situatedness. Born in Chronos, they have to bring us to Aiōn. Inescapably existing in history, art dreams of the untimely. Untimely people have a home that is not in the present age: ‘[…] unzeitgemässe Menschen […]: sie haben anderswo ihre Heimath als in der Zeit […]’ (Nietzsche, UB 4, 1).

One must not confuse the untimely with the timeless. The latter – the Freudian zeitlos – refers to Arche, to an origin, which is independent from the present (‘the unconscious doesn’t know about time’), whereas the untimely – Nietzsche’s unzeitgemäß – refers to the future and is rooted in a critique of the present. The untimely has, therefore, a fundamental critical role producing a problematising gesture in its proper contemporaneous age. Set against the contemporaneous, which refers to all those people and things that live in our chronological time, the contemporary refers to all those people and things yet to come. To affirm the untimely, to escape one’s own time and enter infinite possible worlds one has to resist the dictatorship of the quotidian, to fight the innumerable opinions and clichés around us, to enter a battle against the reactive forces that always privilege the created over the creating, being over becoming.

Contemporaneity unsettles history. A historical order regulating change over time by bracketing the present is wearing thin when the future it holds increasingly becomes indistinguishable from the past. Put positively, the contemporary allows difference to emerge and voices to come together while remaining each in its own time and space, that is, materially singular. As Peter Osborne (2013: 22) says, ‘the idea of the contemporary hypothetically projects an internally differentiated and dynamic spatial-temporal unity of human practices within the present’. Crucial to Osborne is what he derives from the early Romantic project: the necessarily fictional possibility of unity in difference (in the work of art).

This is first of all an epistemological problem insofar as the experience of the manifold (‘the aesthetic’) is put in service of the making, thinking, and knowing of a form (‘the epistemic’) able to hold as difference – as pure force – what the manifold provides. Such form must be fragmentary. Rather than being cancelled out, the aesthetic, which is provided differently in each work of art, is imbued with epistemic powers (its forces). This, taken together, is the site of the contemporary artistic.

However, to date, such an epistemological definition of art does not seem to provide a suitable grounding for ‘artistic research’ since, also in Osborne’s analysis, the artistic is conflated with the fictional. In other words, belief in the reality of ‘research’ are so strong that ahistorical outputs of the kind that the contemporary provides are relegated to the ‘merely’ fictional. The association of the artistic with the fictional pulls the rug from under the kind of epistemological challenge that would need to be raised to take artistic research seriously outside any narrow definitions of either art or science.

Nietzsche dealt with the problem of ‘fiction’ quite decisively, albeit in reverse direction. To Nietzsche, it is not art that is fictional but the position of ‘truth’ compared to which it is assigned that label. (Nietzsche, GD/TI, ‘Wie die “wahre Welt” endlich zur Fabel wurde’ / ‘How the “true world” finally became a fiction’). Thus, in the label of the fictional, Peter Osborne also confirms that his position is that of the philosopher who is interested in but removed from the problem, which is the contemporary artistic at the site of localised material practice. There has to be also an artistic epistemology of the contemporary that does not keep one foot on seemingly secure ground.

One part of the problem lies in the term ‘contemporary’ itself, which coming from the (institutional) history of art carries the belief that something like ‘contemporary art’ exists. ‘Contemporary art’ is – contrary to what Osborne might claim – not a project, but a historical reality borne out of the conflation of the contemporaneous and contemporaneity, the timely and the untimely, as if a present day group of people (‘contemporary artists’) or set of practices was secured already and exempt from the fragmentary.

In the second of his Untimely Meditations, Nietzsche not only warns against historicism – the totalising of history – but also its opposite, the evaporation of history in a ‘suprahistorical’ (ueberhistorisch) standpoint (Nietzsche, UB/UM 2, section 1). This suprahistorical standpoint produces a form of abstract and fictional equality that unifies all difference once it is understood that the different is just at a different position in a spatio-temporal continuum. However, while the suprahistorical standpoint may exhibit ‘wisdom’, for Nietzsche, it does not further life since all space for growth is already occupied, such as in Osborne’s ‘global transnational’ that is ‘the contemporary today’ (Osborne 2013: 26). Artistic research can be pitted against contemporary art as a continuation of an epistemological development toward the fragmentary. It would need to perceive space and time only ever from a specific materially and also historically localised practice without being able to afford the fiction of a suprahistorical, transcendent sphere within which exchange – including knowledge exchange – can take place.