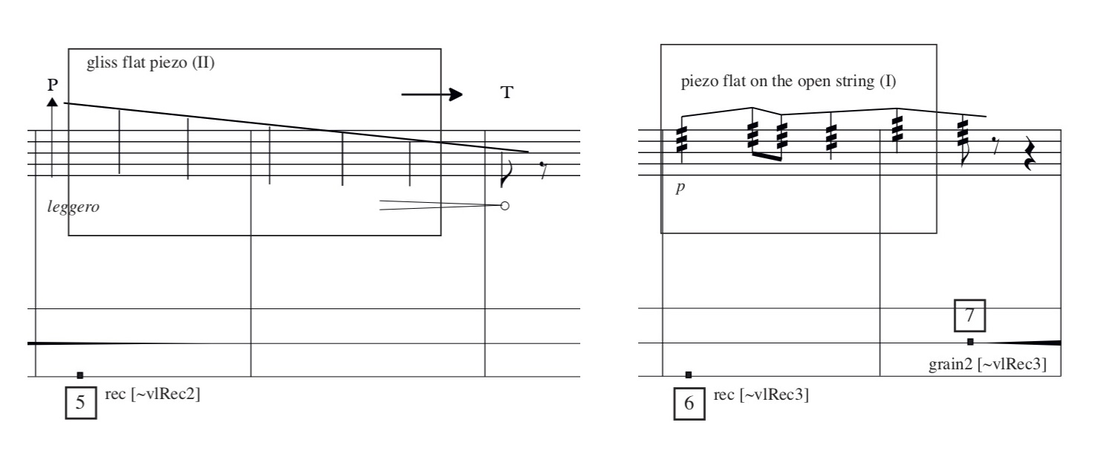

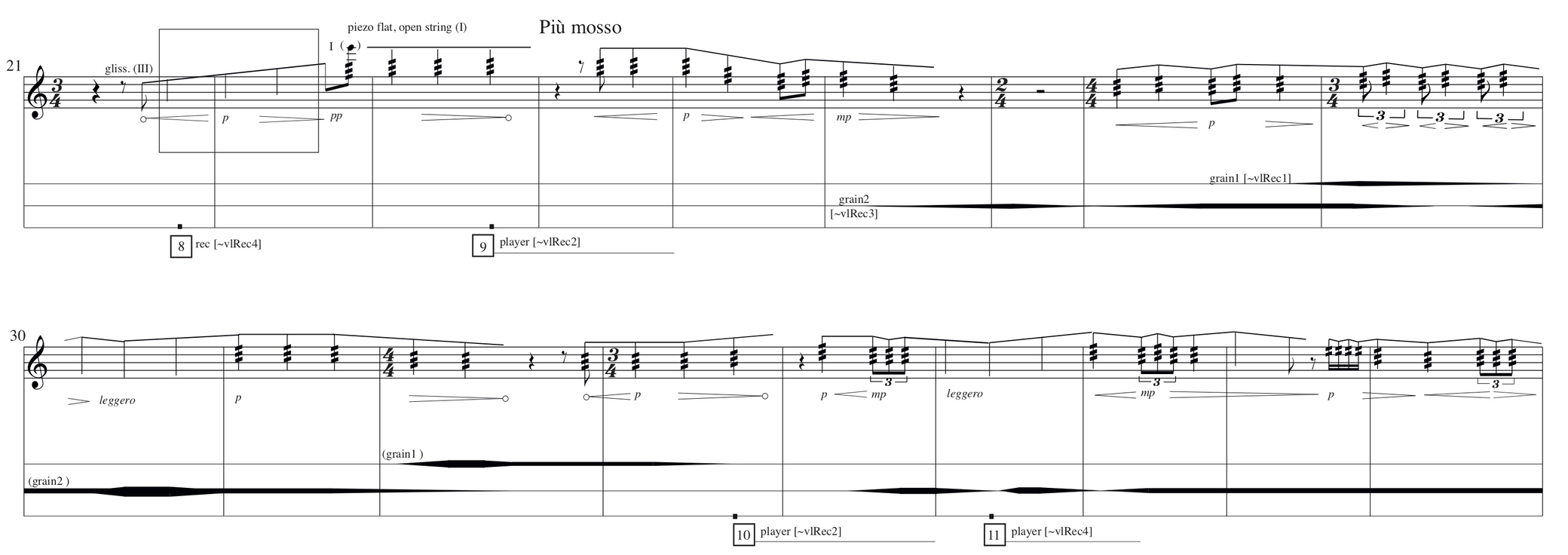

Right after a descending glissando (bb.16-17) is recorded as the buffer “~vlRec2”, as well as the sound generated from the gesture of a tremolo done with the flat piezo on the string, recorded as the buffer “~vlRec3” – fig.3.5.5. These buffers, together with the ascending glissando recorded as the buffer “~vlRec4”, are processed or simply played back while the violin plays, from b.22, a material similar to the one of buffer “~vlRec3” – fig.3.5.6. The processing of these buffers contributes to creating a certain complexity in the polyphony of events happening between the instrumental part and the electronic one – see ex.4. Through repetition, reinterpretation and transformation, all the material presented until now comes into play. So, in this section a limited series of elements is presented through multiple identities. This process of recognition and differentiation of the sound matter lies at the core of my compositional work and it is enabled by the activation of the aural memory, which allows for working on multiple identities of the same material. Relying on the exploitation of a personal archive, the activation of the aural memory is stimulated in the understanding of the sound matter and of its multiple possibilities of manipulation. Finally, the aural memory comes into play not only in the compositional process but also in the listening experience. During the performance of the piece, it is the listener’s memory to be both challenged and guided in the identification and recognition of different instantiations of the same sound material by the constant reinterpretation and re-proposition of a limited series of sonic ideas.

As a general and basic premise I tend to understand composition as a discipline of 'organizing sound', as has been suggested by Varèse:

I decided to call my music 'organized sound' and myself, not a musician, but 'a worker in rhythms, frequencies, and intensities' (Varèse, 1966);

and Cage:

If the word 'music' is sacred and reserved for eighteenth- and nineteenth-century instruments, we can substitute a more meaningful term: organization of sound (Cage, 1937).

The notion of “organization”, can be then understood as referring to the way different sounds are combined within the formal structure of the piece, so within what has been previously defined as the “meso” and the “macro” time scale of music. From the listener's perspective the perception of how the sounds are organized in these time scales happens while the piece is played, so inside the time of the piece itself, or in retrospect, moment after moment during the listening process. Instead the composer has to work in prospect, outside the real-time of the composition, imagining sounds, their succession and combination. Thus it is worth noting how the compositional work happens in another temporal dimension, called the “supra” time scale by Road:

Composition is itself a supratemporal activity. Its results last only a fraction of the time required for its creation. A composer may spend a year to complete a ten-minute piece. […] The electronic music composer may spend considerable time in creating the sound material of the work. Virtually all composers spend time in experimenting, playing with the material in different combinations. Some of these experiments may result in fragments that are edited or discarded, to be replaced with new fragments. Thus it is inevitable that composers invest time pursuing dead ends, composing fragments that no one else will hear. This backtracking is not necessarily time wasted; it is part of an important feedback loop in which composers refine the work (Roads, 2004, p.10).

The “supra” time scale of the compositional process is, therefore, a time outside the real one of the musical composition, and Roads refers here to the non-linearity of the whole process. In my opinion, this non-linearity is not only represented by the time spent in experimenting, going back and forward, but also by the way the composer is constantly shifting between different temporal dimensions, zooming in and out within the different time scales inhabited by the sound material. This recursive work on sound, that lies at the core of the compositional process, triggers a feedback loop between the aural memory and imagination: the composer tends to imagine and anticipate the structural relationships between different sound objects that she keeps in memory while rethinking their definition. This mechanism relies strongly on the possibility of creating a consistent memory of the sound material.

In my personal experience, this means creating multiple ways to get continued access to empirical experience of the sound material and to the different ideas about its definition, transformation and manipulation. The possibility to go back as many times as needed to the empirical experience of sound allows for a better understanding of the acoustic features of the sound material that I am working on, and for a constant redefinition of its aural memory. Thus, I have developed a practice of recording moments of improvisation and exploration, as well as rehearsals at different stages of the process. For each different project or piece, I tend to store and catalogue in digital folders and sub folders different recordings, text files with their description, patches for the processing of sounds, notes, sketches, etc. This becomes a sort of personal archive in which I organize the material that I am working with. In this sense, the term “organization” assumes a different connotation referring to the idea of classification and archive. In this larger meaning, "organization" is no more just a matter of combining the material inside the formal structure of the piece itself, but it refers to the organization of the material outside the piece, within the composer's working environment. During the compositional work, the creation and the organization of a personal archive of information is constantly reshaped and updated, so that this act of cataloguing the sound material supports the non-linear approach to the compositional process, providing the possibility to access and navigate through different information at various stages of the process. Furthermore, the existence of such archives allows for the occasional reconsideration and reuse of a certain element of stored material, providing for multiple outcomes.

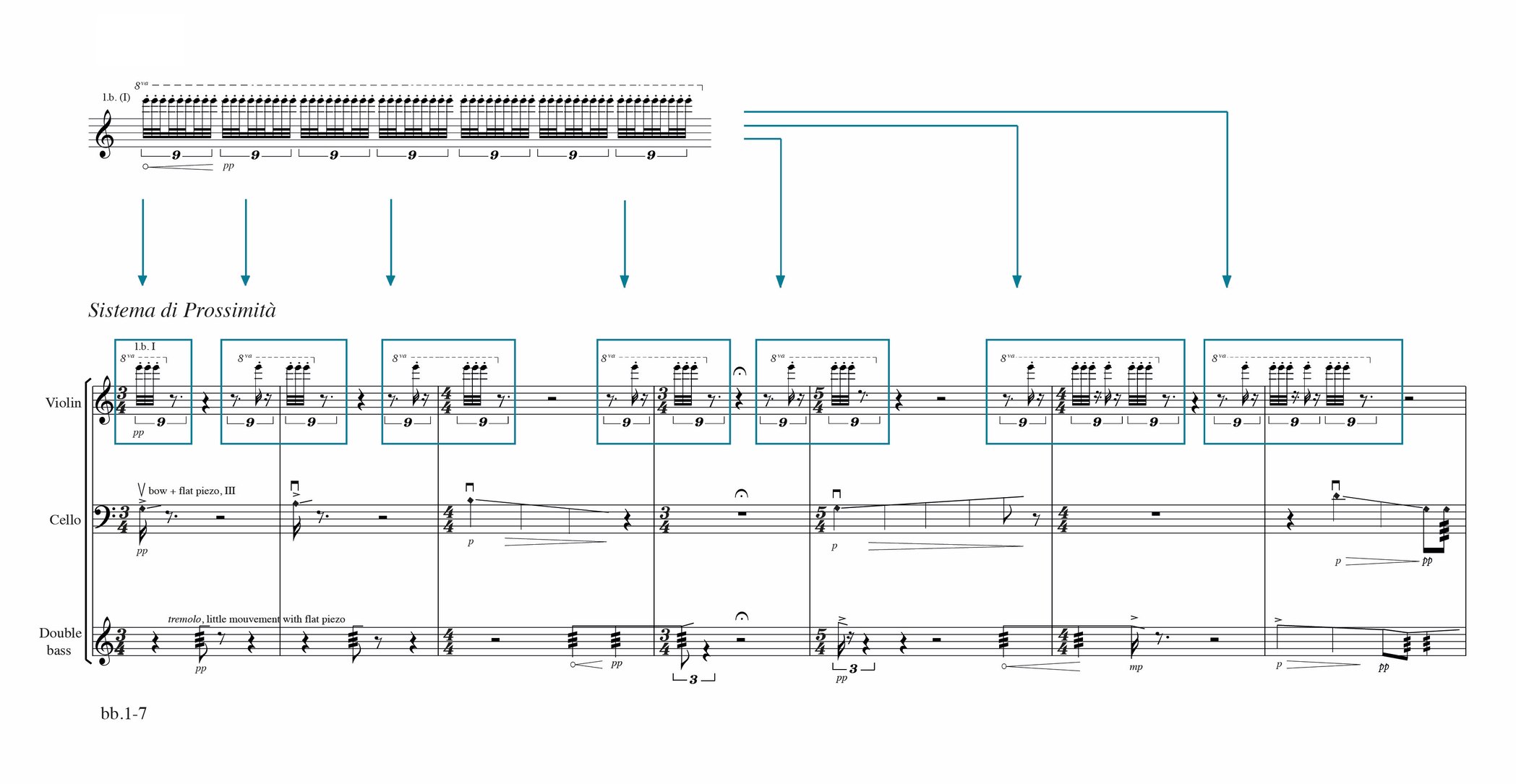

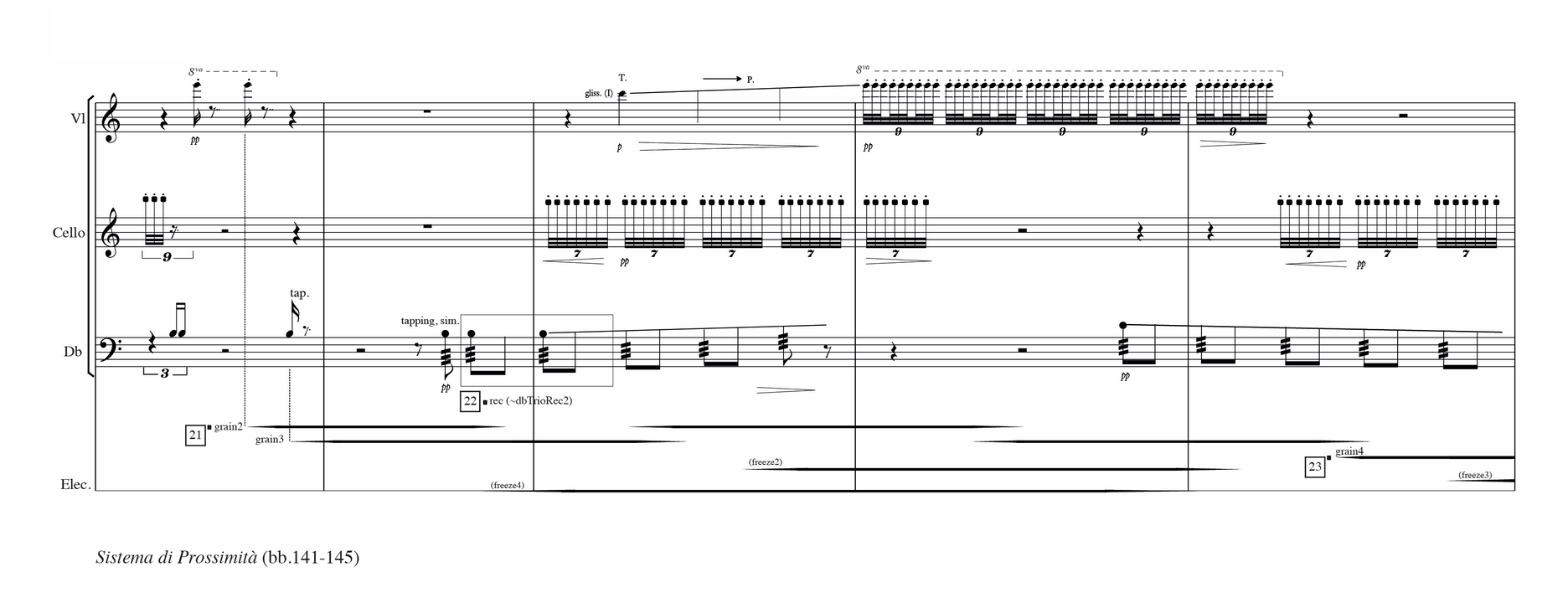

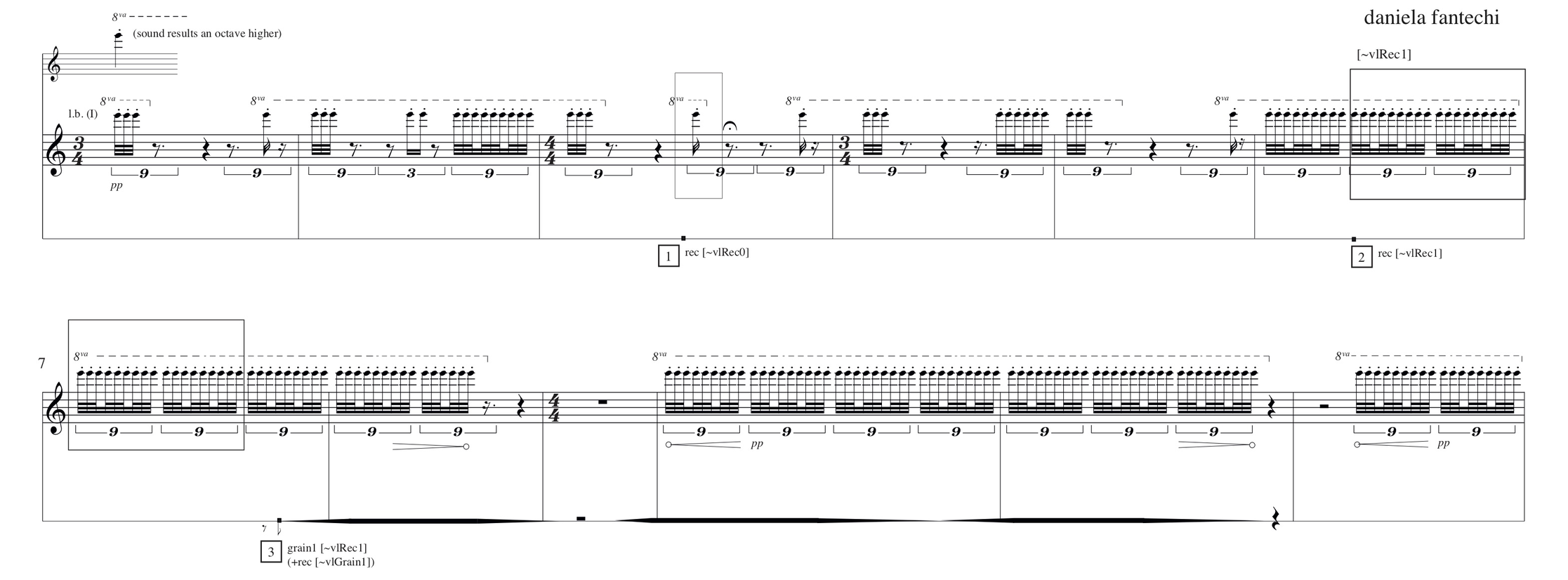

As example I return to Prossimo and the ribattuto sound of the violin, discussed above. Prossimo belongs to the cycle Sistema di Prossimità, which consists of four pieces: Prossimo, for violin and electronics, Prossimo II for double bass and electronics, Prossimo III, for cello and electronics, and Sistema di Prossimità, for violin, cello, double bass and electronics. Each piece of this cycle can be played separately, or one after each other, seamlessly. In the latter case the reuse of the ribattuto sound of the violin, discussed above, is clearly recognizable. At the beginning of Sistema di Prossimità (bb. 1-13) the same sound material appears in a specific rhythmical version (ex.3.5.1), which is the result of a process of subtraction from the original material.

I usually tend to present a certain sound gesture in the instrumental part, to then record it and promptly process it, creating a dialogue with the instrument. In Prossimo, for example, the ribattuto sound is the first one to be recorded in the buffer “~vlRec1” and processed (actually the first sound to be recorded is the buffer “~vlRec0”, which is just a single hit of the same sound gesture, recorded at the very beginning of the piece, but it is processed only later on). So the buffer “~vlRec1” will be the first one to establish a dialogue with the instrumental part, which is playing similar material (bb.7-8 – fig. 3.5.4).

I tried to keep track of the compositional process that can be summarized as follows:

- All material comes from recordings of sounds used or collected for previous pieces. I chose 19 samples among various recordings made for the following pieces: et-ego (for guitar and electronics, 2017), Prossimo (for violin and electronics, 2017), Prossimo II, (for double-bass and electronics, 2018), Residual (for ensemble and electronics, 2019), PianoMusicBox_1 (for piano and electronics). Each selected sample - from 2'' to 30'' – was stored in a folder named “original Buffers”.

- All samples in “original Buffers” were edited and stored in a new folder as “rendered Buffers”. The editing consisted of selecting the most interesting parts and levelling off the amplitude. [software used: Reaper]

- A few spectral analyses were done while checking some possible filterings. [software used: Adobe Audition]

- According to their acoustic features (thickness, textural or gestural shape, register, timbre similarity, etc..), sounds were grouped together in 8 main groups.

- Sound samples were processed through different granulators and filters. [software used: SuperCollider]

- Working within different groups of sounds, a trial track (from 1' to 3') was created for each group. [software used: Reaper]

- Trial tracks were rehearsed on an 8-channels system in two different sessions (27-28/01/20, 11/02/20) at the Orpheus Instituut, thanks to the precious collaboration of Juan Parra Cancino, responsible for the configuration of the 8-channel system. [software used: Digital Performer].

- A few trial tracks and a few samples were chosen to become the actual material used during the final composition of Tickling Forest [software used: Reaper and Illustrator for the score].

The decision of starting from already used material has been triggered by my own theoretical reflection on the notion of archive. During the compositional process, I slowly realized and got confirmation about the actual importance, from the creative perspective, of going back on certain sound materials, taking the chance of better focusing on their nature, and exploiting their potentialities within new musical contexts. Their memory evolves within new utterances, and the archive provides the composer with an environment where letting her own expressivity emerge, through the comprehension of many subtle differences between multiple possible instantiations of the same material. Therefore the setting-up of a work environment based on personal archiving methods contributes not only to enhance the organization within the single compositional process but provides the composer with the possibility of a space of self-reflection. The composer can benefit from her own archiving environment, especially when this is in constant evolution, reflecting the depth of her own personal thoughts and research. The archive becomes the space where memory is built and where processes of artistic self-consciousness are strengthened. Hence, the notion of archive should be intended not only as a physical or digital space to store and get continued access to the sound material, but also – as Laura Zattra proposes – as a process of self-knowledge and awareness.

I believe that this awareness, for electroacoustic composers and musicians, may only generate from the concept of archive, an aspect inherent in the very notion of research. Archiving – by artists, composers, musicians, performers, and scholars – is crucial for several reasons. […] I intend archiving not only as a separate entity (one artist’s physical archive), but also as a process of self-knowledge, of studying and revealing personal lacks and indicating new possibilities for innovation and experimentation; as an action to find the way through what has been already done. […] Archiving means the necessity for the artist/composer/researcher to maintain his/her own materials (that is their own knowledge, culture and practice), in order to become responsible for their own choices, to conduct themselves consciously as artists, to assess their understanding of their own practice, which is the real way to originality and individuality (Zattra, 2018).

The concept of the archive is therefore to be understood as a dynamic process, which provides composers and artists with a deeper awareness of their own work. And working within this mindset can fruitfully enhance originality and support creativity.

>> go to Conclusions

Within this context I found very interesting Patricia Alessandrini's perspective about the role of memory and material, as clearly addressed in her presentation Memory as Difference, Material as Repetition: a Performative Presentation of Compositional Strategies and Multi-source Interpretative Methods (Alessandrini, 2015). Most of her compositional works consist of 'interpretations' or 'readings' of existing repertoire. As it is the case of Adagio sans quatuor (2010), which is based on the Adagio introduction of Mozart's “Dissonance” quartet, Forklaret Nat (2012), written for the Arditti Quartet and based upon an interpretation of Verklärte Nacht, by Arnold Schönberg, or Tracer la lune d'un doigt (2017), based upon a reading of the Adagio movements of J. S. Bach's violin concertos. Her conscious choice of building a personal relationship with the past by using work of the past is influenced by the idea that material is not something that has to be generated, whether it has to be found and interpreted.

I feel that as composer I’m actually performing and interpreting the past through different technologies. [...] I’m somewhat of the opinion that nothing is new, or rather that anything new is just a recombination of things that already exist. [...] I try to emphasise and embrace this idea of nothing being new, but where difference is still possible, and this difference comes about through my subjectivity as a performer, as an interpreter of what has come before (Interview with Nicholas Moroz, 2017).

Most of the pre-existing original materials Alessandrini uses are scored but is not the score that lies at the core of her compositional work. Her method relies in essence on the assembly of electroacoustic maquettes through the layering of various recordings of pre-existing repertoire. The process of superposition highlights the differences between the recordings. In fact, the recordings may be time-stretched proportionally note by note so that, when superimposed, they are synchronized; and the superimposition of these different versions may be subjected to further time-stretching to heighten the subtle variations between them and bring out the artifacts of the phase vocoding. The maquettes are subsequently transcribed into instrumental parts, and they may also provide material for the electronics. Through this process, her instrumental works are started as electroacoustic pieces in order to eventually produce a score, and the identity of the piece is situated in the multiplicity of its practical realization. In such processes, memory provides the possibility of expressivity, in the perception of subtle differences between the various instantiations of the original composition, as well as between the newly composed utterance and the original composition upon which it is based. More generally, I would therefore observe that memory enhances composers' creativity, beyond the kind of material they tend to use. The possibility of building a strong and consistent aural memory of the sound matter allows understanding where differences are still possible, and exactly through the expression of differences, the artist may get to fully express her own creativity. According to my personal experience, I can observe how providing the composer with the possibility to have continuous access to her own classified and catalogued sound material, represents a possible model to work on sound. Such a methodological way of collecting sound materials brings the notion of archiving and cataloguing at the core of the “organization” of the whole compositional process. A source of inspiration for this way of working has been the methodological use of archives and catalogues in the work Systema Naturae by Mauro Lanza and Andrea Valle a cycle of four co-composed works (2013-2017 – see Appendix 4). Setting up her own archive, the composer creates a personal database, a physical and digital space where she stores and redefines sound materials while building and enriching her own aural memory of them. Keeping available access to this database provides a clearer way of developing ideas during the compositional process. Moreover, access to her own personal archive allows for reconsidering already exploited sound materials from new perspectives. For the composer, this is a way of getting deeper knowledge about her own work, and it can also be a convenient and creative way of producing new outcomes. During my research work, gaining this awareness has led me to develop and improve my own habits in building my personal archive. For each new compositional project, I create a specific folder on my computer where I store all different kinds of material - recordings, patches, drafts, scores, etc - with special attention to recordings of my own explorations of different instrumental gestures, as well as of rehearsals with musicians at different stages of the process. These recordings provide me with the possibility of iterative listening which allows me to sharpen the definition of the sonic ideas I am working with. Moreover, the access to these recordings gives me the opportunity to build with them sonic drafts and simulations, using editing software and patches where I can try different processing of the sound material collected.

A declared exploitation of my personal archive is my recent electroacoustic multichannel piece Tickling Forest (2020). I deliberately composed this piece choosing material just from my personal archive of instrumental pieces: all the sounds I worked with belong to recordings of instrumental sounds from different previous pieces. Among the sound material I chose to work with, there is also the same ribattuto sound of the violin, that for this piece has been processed in various ways, using different granulators and filters (listen to audio ex. 3.5.7).

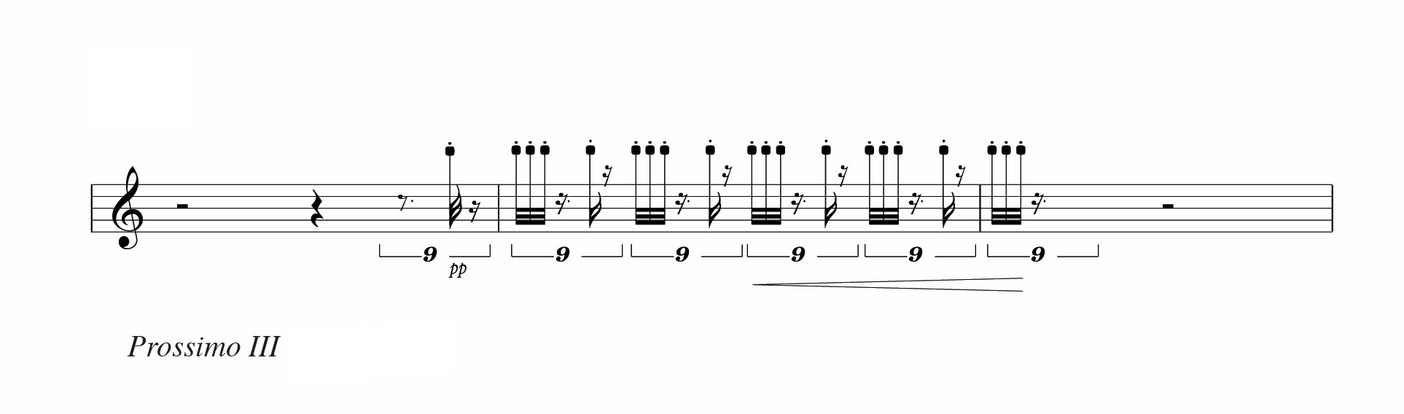

A similar version is assigned to the cello, in the last part of Prossimo III (from b.133 until the end of the piece – ex.3.5.2); here the mode of production – with legno battuto – is similar, and the derivation from the violin's material is evident, even if the timbre and the dynamics are different due to its transposition on another instrument. This sound in the piece for cello also assumes a structural value: it recalls the one already played in the violin piece and, at the same time, it foreshadows the beginning of the trio. Finally, the ribattuto sound comes back at the very end of the cycle, played at the same time by the violin and the cello (from b.134 until the end of Sistema di Prossimità – ex. 3.5.3), and, in a slightly different version, by the double bass as well.But here this ribattuto appears in its continuous form, and, because it is played by all instruments, the sense of texture implied in its original form is reinforced.

The creation of a consistent memory of certain specific sound gestures such as that of the ribattuto, is generated and supported by the act of storing and archiving. During the compositional process, my attention tends to be focused on a limited number of specific sound gestures, corresponding to the ones stored as recordings of explorations, improvisations and rehearsals. These materials usually come to constitute the basis of the formal construction of my pieces. The same recorded and stored materials are also selected for the construction of the electronic part. In my works I rarely conceive the electronic part with the use of synthesized sounds. Rather the electronic is generated by the processing – such as granulations, filtering, delays – of the instrumental part, recorded during the performance.