A sign we are, without meaning,

Without pain we are and have nearly

Lost our language in foreign lands,

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Though the time

Be long, truth

Will come to pass.1

Analyzing these lines in Friedrich Hölderlin's anthem Mnemosyne, Christopher D. Johnson argues that memory "sets us an endless, impossible task in part because we are forever shuttling between the familiar and "the foreign." Language will always remain the most important memory tool for us "because it is fueled by metaphor whose task, as Aristotle and many others after him have observed, is to exploit our thirst for the "foreign," that we might see similarities in things initially perceived as being quite dissimilar."2

The goddess of memory, a Titaness Mnemosyne (gr. Μνημοσύνη), the daughter of Uranus (Heaven) and Gaea (Earth), is the mother of the nine muses, among which are those responsible for inspiring history, art, and literature. Mnemosyne was an inherent part of the mystical Orpheus tradition, in which she was the equivalent of the goddess of oblivion - Lethe, also known as the river of oblivion, which washes the shores of the Greek underworld. In order to forget their former life, the newly dead had to drink from Lethe before resurrecting the new one. The memory represented by Mnemosyne serves as an act of raising eternal truths, so necessary to preserve stories and myths before the emergence of writing.

In the Roman Empire of Augustan times between 44 BC and AD 69, travel and tourism was a widespread phenomenon, an essential cultural feature of the society of the time. Augustan tourism could be explained by three key lexical concepts – peregrinatio, otium, hospitium, and the semantic fields they open. The first of these is important to me in this text. In Latin person who travels around is peregrinator. This noun "comes from the verb peregrinare, which has an ambiguous meaning: it means 'to go abroad, to travel." Travel, in Latin itself, is associated with the idea of "foreignness." The Oxford Latin Dictionary the notion of traveling explains as 'to go, to travel abroad or away from home; to travel in thought or in imagination; to reside, stay or sojourn abroad') and gives the adjective peregrinus the connotation of foreignness. In terms of persons, this adjective means stranger; foreign, alien; of other creatures: not native, exotic; belonging to foreigners, outlandish; of places: situated abroad; not Roman. Augustan travelers were aware "that they remained strangers wherever they were: this corresponds to the much-discussed view of the tourist as 'the Other' and tourism as 'The Quest for the Other'."3

Whether it is the time of Emperor Augustus or the current travel motivation remains the same – the desire to visit and see unfamiliar places, people, experience inexperienced practices, encounter what is not typical of your environment, traditions, no matter how interesting, full of history and attractions your neighborhood is. Cultural researcher Loykie Lomine compares Augustan's tourist to the modern traveler, "New Yorker who has ascended the Eiffel Tower twice but will never visit the Statue of Liberty." The sophisticated Augustan society could offer "everything that is commonly regarded as typically modern (not to say post-modern) in terms of tourism: museums, guide-books, seaside resorts with drunk and noisy holidaymakers at night, candle-lit dinner parties in fashionable restaurants, promiscuous hotels, unavoidable sightseeing places, spas, souvenir shops, postcards, over-talkative and boring guides, concert halls and much more besides."4

Such Roman-era traveler is so little different from the thirsty for pleasure and adventure modern tourist that the very concept of travel and its accompanying practices seems to be an unchanging and essential axis supporting human civilizations. Travel is always accompanied by the traveler's need to redefine himself repeatedly through "the Other" so he could get a broader experience than that defined by his relationship with the world. Only "the Other" enables him to transform himself, to himself become "the Other."

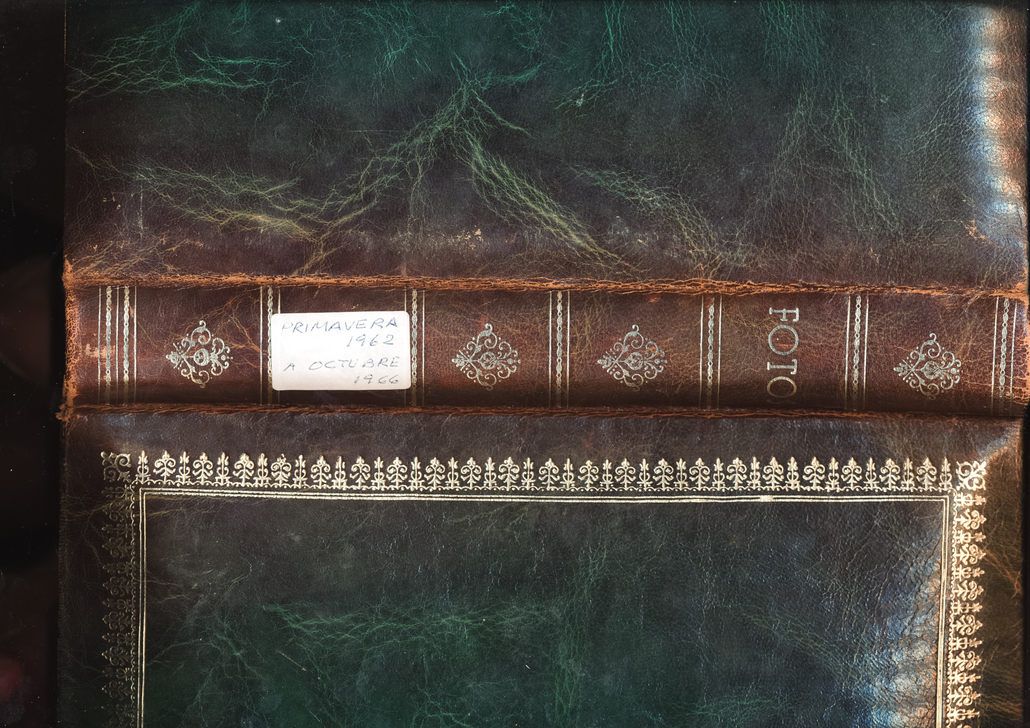

Like the Augustinian traveler of the Roman Empire – peregrinator, the artist is always "the Other": a foreigner, an alien – an eternal stranger in unfamiliar territories. A traveler of time, media, archives, experiences, pulling the truth out of memory, and filling the gaps with lies. The methodology of my artistic research is simple - I travel through archives and historical material as an inattentive tourist who wonders everything he encounters and looks around without knowing what awaits him turning a corner in an unfamiliar city. The viewer of my work also becomes a tourist wandering through the pages of my artwork. It gives him the coordinates, a travel guide written by me is given to him to avoid getting lost where he is now, where he was or will be. The gaze of my artistic research is the gaze of a tourist. The primary purpose of such a tourist is not to reconstruct the past or shape the future, although this sometimes happens unexpectedly, unknowingly, without planning for it. He is only trying to quell his "thirst for foreignness" by traveling through libraries, museums, archives, visiting monuments, participating in commemoration practices. Traveling from a homogeneous, institutionalized memory, he can suddenly change the direction of his journey and visit his past generations, relics, family myths, and hidden fantasies regardless of any logic and order. From such a close relationship with the other - others become his own, begin to define his own. The travel photo albums of such a tourist are filled with unknown family photos, unknown stories, adventures, and landscapes. When a turning point occurs when such a tourist begins to assimilate foreign myths, stories, and archives, when from being "unfamiliar" they become "his own"?

This presentation is an attempt to look at my creative field, and to define my artistic research practices and methods from a memory studies perspective.

Who owns the memory? Is it only a personal part of the individual or a collective right capable of drawing not only internal maps of the personality but also of creating atlases of the world? To paraphrase cultural theorist Astrid Erll, the field of cultural memory studies attempts to understand the different ways people deal with time, understand the present and imagine the future.5 Memory never walks alone; what we remember always depends on what path we take, what cultural plane we live on, and what we believe.

In an attempt to capture a paradigm shift that has changed the relationship between history and memory in recent decades, Aleida Assman argues that "the past appears to be no longer written in granite but rather in water,"6 this water periodically ripples and constantly changes the course of politics and history. Memory "does not preserve an original stimulus in a pure and fixed form." However, it has become an actively used source of government and identity policy: "In addition, we have come to accept that we live in a world mediated by representations in the form of texts and images, an acceptance that has had an impact on both individual remembering and the work of the historian."7 Collective memory as defined by Edward Said in his essay Invention, Memory and Place, "collective memory is not an inert and passive thing, but a field of activity in which past events are selected, reconstructed, maintained, modified, and endowed with political meaning."8

Astrida Erll suggests thinking about memory not as a phenomenon framed in the context of local, regional, state, social, or religious groups but as an utterly transcultural action that constantly migrates between territories and social boundaries. Such a glance through her so-called "transcultural lens" can provide a much deeper understanding of a global world in which memory travels and constantly rubs off boundaries and structures. It is also an opportunity to see how the deposited historical layers of thought shape our relationship with the present. The 'traveling memory' metaphor that Erll is offering is developed on the basis of James Clifford' traveling culture" idea9, in which he defines culture as a dynamic process unable to create a stable portrait of himself, and the ideas of Aby Warburg, the pioneer of memory research and the creator of the Mnemosyne Atlas, on the transcultural migration and travel of symbols. According to Erll, traveling memory is a relationship, a transcultural experience of memory. Memory travel in five dimensions of movement: people who travel – memory carriers, traveling content – images that recur over the years, traveling media – knowledge, and practices and forms what are traveling. Erll states that "all cultural memory must 'travel,' be kept in motion, in order to 'stay alive,' to have an impact both on individual minds and social formations.10 If memory remains alive only by moving and constantly changing positions, as Warburg and Erll thought, the journey becomes the most crucial necessity for the survival of memory.

Those who play the same computer games, watch the same series on Netflix also take part in these "memory journeys," where props and fiction become the backbone of memory gaps and the basis of new hybrid identities. The Polish national pride, the computer game" The Witcher" based on Slavic national heritage and folklore, is described by American president Barack Obama as "a great example of Poland's place in the new global economy." On a personal level, meanwhile, this game becomes a motivation for individuals of Polish descent to form their own "Polish-Witcher" identity: "Everyone has their way of connecting with their heritage, and The Witcher helped me connect with mine. I feel more in touch with my Polish family. I'm proud of my Polish background, proud of being a Witcher fan, proud of working up the courage to throw myself into the unknown."

"The Viking Fight Clubs" and their members fighting with plastic star wars props are being held next to the Museum of Modern Art in Sao Paulo Ibarapuera Park, or the communities of Capueira in Lithuania, which are creating a new hybrid organization based on Brazilian cultural heritage and memory, are also the consequences of transcultural memory journeys. If a plant is at risk of extinction, it can be transported and stored elsewhere in the world. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature classifies 60 million years old Ginko Biloba as an endangered species in the wild. When you walk in the parks of Paris or Washington "on those bright golden fans scattered on some rain-darkened sidewalk this fall, you're having a close encounter with a rare thing—a species that humans rescued from natural oblivion and spread around the world. It's "such a great evolutionary story," <…> "and also a great cultural story."11 It is similar to the rituals and practices of memory and cultural heritage. With the disappearance of some cultural phenomena as some rare plant species in unfavorable soils, they can be preserved by transportation. Artistic creation can also act as an example of such transport - what has long been "extinct in freedom" can be reborn in works of art.

The field of art can be equated with the definition of "traveling memory" because a work of art is able to accommodate all the dimensions of the memory journey defined by Erll: to travel like a memory carrier, media, form, content, and practice. Not every artwork claims to be a cosmopolitan readable entity that evokes a universal experience independent of place and time, but usually, the artwork has the ambition to be more than just local. Physically influencing a work of art also awakens a memory of a distant, deep past, and in this respect, art is probably the only way to reach such a deep past and to "remember" it.

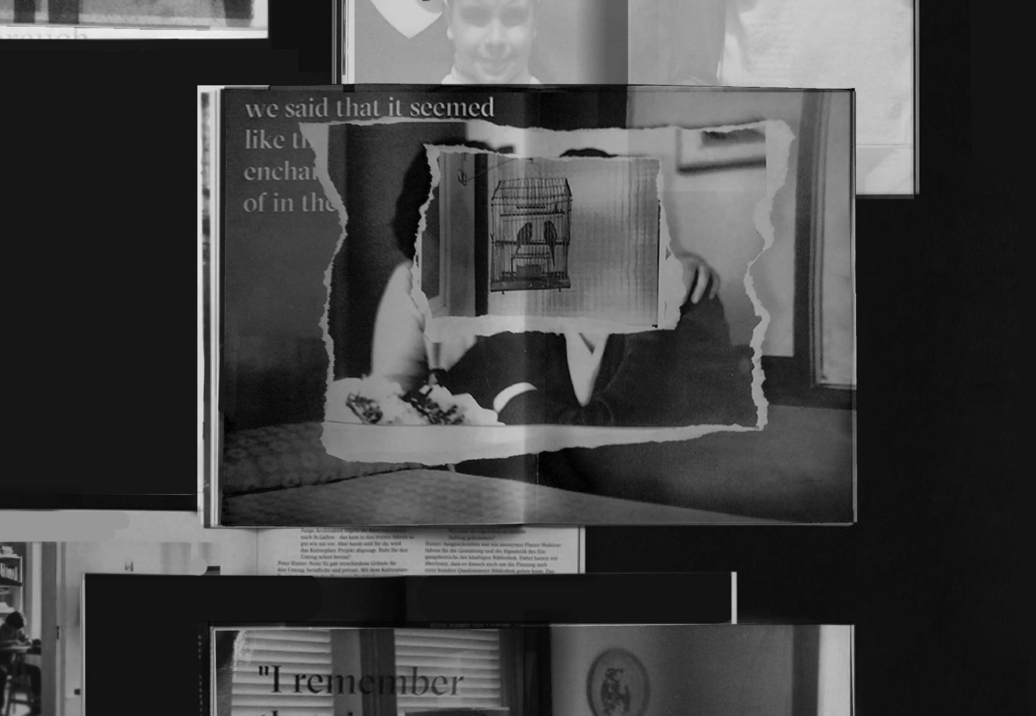

Erll's ideas of "traveling memory" and "transcultural lens" allow me to define the methodology of my artistic research as well. When an artist creates an artwork, he is a medium, a lens, a crystal through which the transferred memory concentrates at one point, or vice versa. Even the most transparent glass distorts. What does the sorcerer see in crystal ball when asked by a tourist strayed into a divination salon to tell him about the future? Do mystical powers help him, or does he use something similar to Sherlock Holmes' method of deduction - in other words, he tries to predict the future by learning as much as possible about the past of the visitor. There are several similarities between the work done by this sorcerer and the practice of the artist. The artist enchants, prophesies, reminds, remembers, but also forgets, formalizes, stabilizes, confuses, misses, and destroys. One way or another, if a higher force in his creation does not drive his hands, he is constantly traveling and always using memory archives.

Marta Frejute (…) It all looked like things and wonders described in the story of Amadi. (…)

Wood, organic glass, print, 2020, Contemporary Art center, Vilnius

(…) It all looked like things and wonders described in the story of Amadi. (…)

Marta Frejute Wood, organic glass, print, 2020

Friedrich Hölderlin, Hymns and Fragments, translated by Richard Sieburth, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984, p. 23.

Wegeberichts – descriptions of Lithuanian roads sent to the Marshal of the Teutonic Order are the oldest source of Lithuanian historical geography. For many crusader reconnaissances, Lithuania is only swamps, forests, and morass, which can be passed only in winter, when the waters are frozen. Subsequent visitors emphasize misery and bitterness, barren lands, barbaric and cruel customs, and drunkenness. One such example is the description of Lithuania, made by the envoy of Emperor Maximilian I, Sigismund Herberstein, who traveled in Lithuania in 1517 and 1526: "The climate is northern, all animals are small. The land has much grain, but the crop rarely ripens. The people are impoverished and oppressed by severe slavery."12 Such impressions of travel around Lithuania seem to extend the first tourist experience in Lithuania found in written sources. The journey of the monk Brunon in this country ended tragically and thus marked the beginning of the written mention of the Lithuania name. The image of the gloomy barbarian land travels with works of art, whether it be Merime's "Lokis" or "The Silence of the Lambs." How many future travel albums and guides have to be written to forget these first memories of traveling to Lithuania?

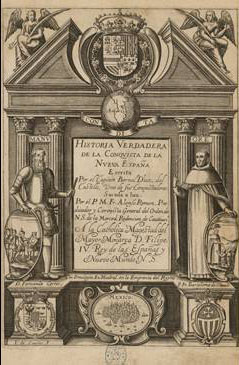

The pioneer of the modern travel guide genre can be considered the British writer Marina Starke, 1802. published a collection of memoirs on a trip to Italy, sharing his observations on Italian churches and villas, tips on safely passing the battlefields of the French Revolution, and developed the first rating system, marking a point of interest with one to five exclamations. The famous British publisher John Murray borrowed from Starke ideas such as grouping sections of the book into itineraries, places of interest, and pub lists, and in 1836 published the first series of travel guides, a prototype of future travel guides, The Guide to Continental Travelers. In Germany, publisher Karl Baedeker, following the example of Murray, fills the market with his own guided publications advising the European bourgeoisie on how to travel independently without high costs. While knights novels helped the Spaniards colonize America, Baedeker's travel guides were used by Germans as reference for bombing during World War II, and Lonely Planet's 1994 guide to the Middle East, according to American Ambassador Barbara Bodine, helped American troops occupy the country.

Like modern tourists traveling with Lonely Planet travel booklets, the 16th century Spaniards transported medieval fairy tales to the New World. The knights' novels, which strongly influenced the people of Europe and greatly influenced the conquistadors13, their mystical characters, and the incredible phenomena they described, became an inspiration for describing what was unfamiliar to Spaniards. Bernal Dias del Calstiljo writes in his book about the conquest of Mexico: "I have not earned anything in life that I could leave to my children and descendants, only this true story of mine." As a witness to the events, he believes he is a much better source of truth than other non-participating authors of the story, despite their more significant writing advantage. This good writing style described by Dias had kept him from his pen for as long as thirty years: "I was writing, I accidentally saw what Gómara, Yllescas, and Jovio wrote. When I read their stories and appreciated their polished style - I realized how rough and unrefined my own story was, I stopped writing."14 Although belated, the desire to tell his version of the story and correct the mistakes made by his contemporaries eventually prevailed. Such a desire is often the primary and only source of creative motivation.

The historical source, the experience made public by Conquistador Dias, and the traveler's story opened new horizons for his descendants. Memory embodied in texts, works, photographs, autobiographies, and publicly published memoirs becomes a part of the public debate that is constantly being supplemented, corrected, and appropriated, it no longer belongs to the person who shared it: once words "are verbalized in the form of a narrative or represented by a visual image, the individual's memories become part of an intersubjective symbolic system and are, strictly speaking, no longer a purely exclusive and unalienable property." 15Telling how you remember it is also to form how you will be remembered, to create a guide to your past, indicating the coordinates that the reader of your story could follow. The ability to control how you will be remembered is an eternal pursuit of immortality. Executing the past can become a challenge not only to leave as much evidence of your life as possible but also to erase it. The hero of Kundera's novel "Immortality" faces this problem of formalization and tries to fight against this "immortality" that has been settling in the archives for centuries. Like a criminal who tries to destroy all the remaining evidence after the crime has taken place, he begins to destroy photos of his life. He considers these archives of his life only as his personal affair, which causes his daughter's, who represents collective memory camp, anger. She considers these archives also her property, defined by images and reminiscent of who those people (previous generations of her family) are and who she is. She accepts such an act of destruction as an attack on her network of identity.

When "a poet or artist remembers, whose memories does he experience? Does he choose to, say, drink from the Mnemosyne pool, or does he drink involuntarily, not knowing maybe he is already drunk on Lethe?"16 This question, which Christopher D. Johnson raises when analyzing Hölderlin's poem, is also crucial in the context of my artistic research. The work of art is always in tension between memory and oblivion, between the waters of Mnemosyne and Lethe. As Elena Esposito defines this problem: "In remembering one faces the world; in forgetting one faces oneself - a circumstance of yourself is a circumstance that will always create problems for all approaches that believe the two references to be independent."17 Art helps to experience oblivion, the inability to associate one's experience with any memory, filling the emptiness with fantasy experiences and symbols that provide comfort while being fictitious. It is an opportunity to resurrect the ghosts of the past and break ties with the same past. Does the artist not create to forget, does not dig up the bones of the ghosts who visit him only to bury them decently. In our culture, the burial phenomenon is an integral part of the culture of memory, an action necessary for the deceased to enter the afterlife or return to the life cycle. The unburied ghosts of the dead roam the earth forever, becoming intrusive visitors to the present, not giving peace of mind and raising moral questions, doubts, reminiscent of guilt and mistakes. Here a new opportunity arises for creativity and its meaning in life. To create artwork as an act of remembrance just to be forgotten.