Back to the portal

Introduction

I am neither a classically trained musician, nor a trained composer. The practice described here comes from my background in directing and scenography. My work with sonic scenography brings me naturally close to musical composition. I am therefore entering this field through my practice. In my research, music derives from an urge to understand the spatial characteristics of sound and the desire to discover and reveal the physicality of sound in relation to space and time. In the creation of sonic worlds, I strive for musical expressions that are spatial, site-sensitive and communal. Consequently, the sounds that I search for need to be produced by the participants and transformed by the space. It matters profoundly how the sounds live in the space. If the created sounds are not brought into a deliberate dialogue with the space, they are not spatial expressions. The challenge as well as the inspiration for my musical creations exists in the dialogue with the space. The inherent dependency on the space demands imagination and inventiveness throughout the creative process, which I share with the participating instrumentalists, regardless of whether they use voice or other instruments.

In the following text, I reveal the aspirations and methods of my work, including sketches that I use to support my work when composing in space.

Composing as a spatial practice

Co-creation

Space - director - performers - audience

I see myself as the creator of spatial sound compositions in the way that I develop a concept based on my knowledge and experience in this form of art. I initiate a project and I lead it. I shape it and I direct the performers. In one sense my role as the author of the work can be seen as quite traditional, and the works are credited to me. At the same time, the process that unfolds through workshops opens up the act of collaborative creation. During these workshops, I teach what I know about spatial sonic expression and how to collaborate with a space. Together, me and the performers learn from the space. We discover project-specific tools, phenomena, and understandings. The creation is based on participation, and the responsibility for how we create is shared. Together we bring something into existence.

In the creative process I take on several parallel and overlapping roles. Thinking of different agencies as co-creators generates an area for play and a freedom to explore which I need in order to be creative and not only constructive. It opens up my mind. My musical creation does not start from thinking about music, but rather, it arrives in music. First, I am concerned with the character of the space and with the individuality of the participants. Next, I explore the relations that are already there and those that can be developed. Through the exploration of the properties of the individual elements and the correspondences between the agents influencing them, shapeshifting forms and their evolving mattering(s) transform - and spatial musical expression develops. By ‘mattering’ I mean that sonic entities, which are usually understood as energy and not substance, shape physical forms that can be experienced and accessed physically. (see mattering in the dictionary)

Sonic entities

Sonic entities reveal different sides of their character in their movement through the space. How do they contract and expand? How do they relate to other entities? How do they reveal what they are made of? What matters them? What stays as some kind of essence as they disappear? Which parts are most fluctuating or easily transformed?

Spaces

Spaces always exist as co-creators of works that are sensitive to them, and even of those that are not - but they are typically not acknowledged as such by most parties involved. I see spaces as co-creators and I work with them as dialogue partners, making use of all my senses. I learn from the space. Its temporality guides the spatial sound composition. Its acoustics are co-responsible for the sounds we create. Even more, the instrument-expressions are dependent on the space, and they are not considered complete without their transformation by the space.

Performers

Whether alone or as a group, performers are complex co-creators. They are individuals who lead lives outside the performance space. Their voices as instruments are shaped over time and by experience, and also vary in shape and ability from one day to the next. They are complete-but-not-closed visible bodies which can expand invisibly through sound. With each in-breath they hold the possibility for something unique to be revealed in the present moment with the out-breath.

In order to be a co-creating performer in my works one has to listen inward and outward continuously. It is a generous and brave act to truly listen. When this inward-outward-listening has been explored sufficiently, the acquired understanding gives a security that one can adjust to any change in context. Working with breath and movements in relation, the performers never only direct their expression outwards. Their expression is always in relation to impressions from their surroundings.

Sound has to be created in order to exist. Sonic entities, spaces and me as director are all dependent on the participants as the creators of sound. What turns the creator into a co-creator is their active involvement in the shaping of the work. Because their individuality matters, and since their tuning into the group and into the space co-shapes the spatiotemporal musical expression, they influence each step along the way.

Their performance co-creates the work every time it is performed. Each performer’s understanding of their relations to the other co-creators secures the unfolding of the performance. Their flexibility holds the openings that allow for the audience to move freely inside the performance.

Audience

Finally, the audience also contribute actively as co-creators of their experience. In my works I encourage this firstly through the possibility to move around inside of the performance and to follow one’s own curiosity, and secondly by creating a choreographed sonic work that opens up different perspectives and which stimulates further exploration. Composer Walter Gieseler writes that the audience needs to receive a phenomenon in such a form that it can be experienced through the senses. For him this is also connected to ‘discovering sense’ (Gieseler, 1975). In German the word sense (“Sinn”) translates as sense as well as meaning. Sensing and thinking here reveal their connection. The immersion that takes place in my work functions as an envelope that triggers wonder and discovery, reception, and contemplation.

Working with co-creators

attention - creation - perception

Because sonic expression is relative to all elements on site, and is only spatial when all agents are present, I usually hold workshops on site to develop together how to shape and co-create spatial sonic expression.

What I mainly do when giving workshops is to enable re-sensitisation - to sense more, both inwards and outwards. I cultivate an awakening of the senses that have been dormant as a way to investigate with all our senses and to let them guide our creative process. This sensing is not to be mistaken with feelings and emotions. It is an inquiry that uses the minuteness of our senses to find precision.

To respects one’s encounter with the space is one of the first things to learn in a collaboration with me. When I enter spaces with a caring, respectful, and curious attention, I get the impression that the space opens up to me. I listen into the space and into its innate potential for sonic interaction. (see listen into in the dictionary)

Sound is a vehicle to explore the performance space and helps to playfully engage with the others that are present and to explore self-expression and self-reflection. But first, we need to listen. What is present in the space? How does the space react to our quiet presence? Can we hear the immediate surrounding? How does my body react to the space? What areas does my attention get drawn to? How does it feel to share the space? In a multimodal sensing we react to the air, the light, the temperature. Listening can take place on many levels. It is a reaching out with our aural sense but also with the other senses. It is an active receiving that notices those impressions that can only be registered by ways of listening carefully with the whole body.

During our first meetings, when I don’t know the participants yet, I introduce listening exercises, physical awareness tasks and sound games. One of these games is the Sound-Ball Game. Standing in a circle, one person has the sound-ball. The ball is materialized with the help of one’s hands and a vocal expression. The form of the ball is expressed through sound as the ball is formed in the hands. The ball can range from tiny to huge. It can be heavy or light, soft or hard, or more flexible like chewing gum, anything goes. The sonic expression and the way it is thrown towards another person reveals its characteristics further. As in any other ball game, eye contact before throwing is helpful here. The person who catches the sound ball accepts the sound as the ball reaches their hands and receives it with an according sound. The ball is then shaped with the hands and voice anew, before it is passed on.

I also initiate improvisations where acoustic phenomena are explored individually in a space. The sound and the space can herein be brought into an active transformative dialogue affecting and altering both sound and space. When I expand these improvisations into group improvisations, we widen the experience of transformation into an understanding of the relational experience of spatial sonic phenomena. When, for example, we hear one sound and then add another sound, it alters the perception of the sound that we heard first. Our experience of these sounds becomes relational and, in this co-presence or in the temporal progression of the sounds, we experience characteristics of the individual sounds that we did not notice before. These exercises playfully connect us to each other and allow for us to tune in to each other and to the space. The exercises show rather than tell what we will work with. In this process I also learn more about the participants individually and as a group. I am interested to learn more about what they care about, where their curiosities intersect, what sonic expressions they feel comfortable with and how much they are used to engaging their body as a facilitator for sonic expression.

Sharing thoughts in the group is an important part of this process. Finishing a task or a meeting with a round of feedback where we share our experiences has high priority. This feedback-round is a mirroring of experiences and an expansion of one’s own experience through the experience of the others, which becomes a pool of shared experience and knowledge. Together with the participants, I share a common intention towards a theme which can be local or universal. This perspective guides our search. As the participants grow more familiar with my methods of embodied spatial listening and sounding, the explorations become more specific. This can, for example, lead to a narrowing of the focus, a deepening of an investigation or the stretching of a relational aspect. Through listening, the placing of sounds and performers, changing positions and through movement, spatial sonic potentials are explored individually and in combination. Observing these inter- and intra-actions guides my suggestions for practical tasks and the musical explorations in the creation of an open work. Here, interaction is the understanding of cause and effect between entities within the explorations. As important, however, is the deeper search, the search through intra-action, where the ability of the entities involved emerges from within their interdependence. As Karen Barad suggests, “relata-within-phenomena emerge through specific intra-actions” (Barad, 2003, p.815). The result becomes an open work in accordance with Umberto Eco’s definition, where the artist leaves elements of the work – in my case performance – open to the audience and to chance (Eco, 1989).

Usually, it is said that the director is the first audience for a piece. In many ways this is also true in the creative processes I initiate. But due to the strong emphasis on listening with the whole body it is also important that all participants join me in taking on the role of the audience. The awareness towards the space, the feeling of being surrounded by its architecture, the sensing of the sonic reaction of the architecture and the presence of the performers creating the sounds all around, teaches the performers a great deal about what is important for the guidance of a free-moving audience inside a spatial musical performance. In our feedback rounds during the workshop days, the relation to the audience is a reappearing topic. We are aware that the microcosm we are creating exists to allow for individual and communal exploration by strangers. The aim is to create an environment for the audience that allows for an open and explorative mind.

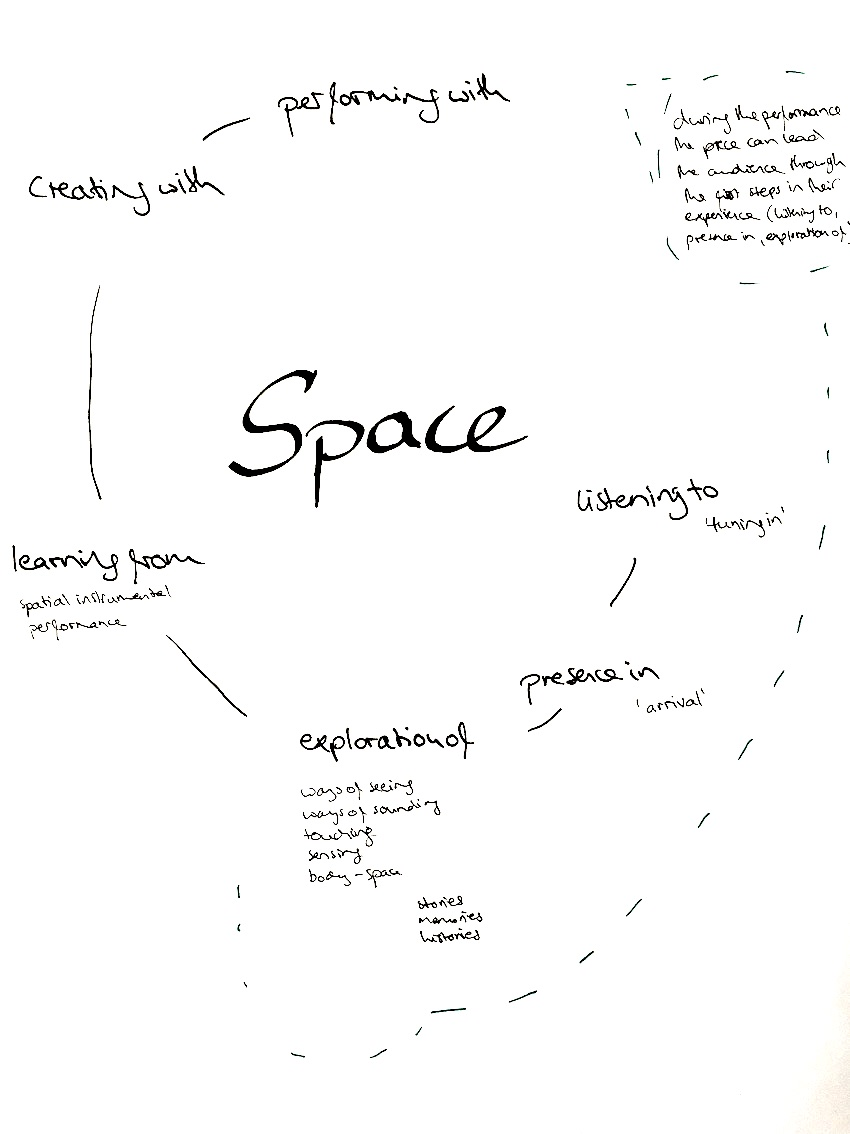

It starts by listening to the space. This is a listening with all senses. It is a tuning into the space and its temporality. This phase is followed by the acknowledgement of our own presence in the space. I also think of this as an arrival. It gives the opportunity to make choices about what to bring into the space and what to leave outside, including thoughts, emotions, and impressions of all kinds. This phase also relates to space-care (dictionary) as a way to connect to the space on several levels and tend to it, to work with it responsibly. A next and more active phase is the exploration of the space. It is an investigation of and an engagement with the space and with all that it holds, including the other co-creators, by means of seeing, sounding, touching, sensing and interacting in other ways. It involves full-body attention and explores the active relationship between the ‘own body-space’ and the ‘surrounding body’. This phase can additionally include conversation with locals, storytelling, sharing of memories, researching history, and more. Learning from the space builds on the interaction with the space in the earlier phases. We now integrate this new understanding into instrument-specific explorations with the space. Each instrumentalist learns how their instrumental expression is changed and expanded through the space and how one can use the expressive potential of one’s instrument in a site-sensitive way. By working this way we search for instrument expression that is spatial and conditioned by site. For voice I call this spatial vocal expression. (see voice in dictionary and Spaces as Voice Teachers) By now we have learned a lot about and from the space and the other co-creators. As the material for the performance develops, so do the connections and structures. Through spatial improvisation developed based on the evolving material and structures, we discover their temporal shapes. The creation with the space is a shaping of form and content through inter- and intra-action. Gradually this leads to performative works shared with an audience. Each performance is a performing with the space, the space takes on an active role as co-performer, rather than being reduced to a ‘container’ or frame for the work.

In the top right corner of the drawing, you can see that the performances are created in such a way that the audience will experience the first three steps as the performance unfolds. The listening to space, presence in space and the exploration of the space are provided and made accessible through the performance - restricted by the fact that the audience are active but quiet co-creators.

Moving (with) sound - Sonic choreography - Dancing music

Moving sound is firstly a continuation of the placing of sound. It is in the nature of sound, as pressure waves, to move through the space. As sound meets and bounces back from surfaces in the space, it is manipulated by its environment. Sounds are, in my works, also moved in the space over time as the performers move with the sounds they utter. For all participants, instrumentalists as well as audience, it furthermore becomes a moving with sounds. A simultaneous movement of sounds by performers and movement by the audience creates an active exploration of sonic forms in interaction on both sides. Shifts of aural perspective are a consequence of this movement. When audience members move through the space, it changes their relation to the placed sounds in the space just as much, but differently, to when sounds are moved around them as they stay in one position. The change of a body of sound is created in the space, with the understanding of how time will simultaneously affect its body. Moving sound through the space forms sound differently. The performer moves forward and leaves the sound behind them as well as projecting sound forwards. When actively moving with sound the ephemeral quality leaves traces of physical and material intersections.

Movement creates interaction. When sound moves in the space, the architectural elements alter the sonic character of the sound. As I deliberately use this quality in the interaction of sonic bodies with the space, this brief effect can be used to create a kind of sharpened shadow that creates another sonic layer.

To move sound bodies in relation to a space turns the spatial sound composition further into a living composition - living music. The vibrant character of spatial acoustic music gives the possibility to physically experience the choreographic dimension of a spatial sound performance. The sonic architecture is a living form inside a static architecture that takes part in its transformation. The sonic scenography is a seductive all-surrounding perfume constructed of sound for the audience to be immersed in as it unfolds its layers.

References:

Barad, K. (2003) ‘Posthumanist Performativity: Toward An Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter’, Signs, 28, pp. 801–831. doi: 10.1086/345321.

Böhme, G. and Engels-Schwarzpaul, A.-C. (2018) Atmospheric architectures: the aesthetics of felt spaces. London New York Oxford New Delhi Sydney: Bloomsbury Visual Arts.

Carrier, M. (2009) Raum-Zeit. Berlin: de Gruyter (Grundthemen Philosophie).

Eco, U. (1989) The open work. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Gieseler, W. (1975) Komposition im 20. Jahrhundert: Details, Zusammenhänge. Celle: Moeck.

Oliveros, P. (2005) Deep listening: a composer’s sound practice. New York, NY: iUniverse.

Oliveros, P. (2006) ‘Improvising with spaces’, The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 119(5), pp. 3314–3314. doi: 10.1121/1.4786316.

Rovelli, C. (2018) The order of time. London: Allen Lane, an imprint of Penguin Books.

Composer and musician Pauline Oliveros improvised together with musicians in spaces with her deep listening practice. In doing so she recognised how spaces influence musical improvisation. Her Deep Listening Band created music in interaction with unusual spaces (Oliveros, 2006, p.68). In her book Deep Listening, she described that she was concerned by the “disconnection from the environment that included the audience as the music was played” (Oliveros, 2005, p. xvii). I see many parallels in our listening practices and in the attention that we give to ourselves and our surroundings. However, as far as I can understand her work from studying it without ever having experienced it myself, her practice seems to strive for self-development and well-being. Even though my practice brings attention to each individual, its impact addresses that which surrounds it and that which it interacts with. My practice cultivates a togetherness that is enabled by the attention the performers bring to the space, and their active dialogue with it. The making perceptible of the space, by means of sonic interactions between the performer and the space, connects the individual performer and audience member to the surrounding and the self. Pauline Oliveros suggests that “listening with eyes closed in order to heighten and develop auditory attention is especially recommended” (Oliveros, 2006, p.68). In my work it is the employment of multimodal sensing that supports an attentive full-body listening. The atmosphere in my performances can be contemplative, but it is not meditative. The audience members are not observers but in an active synergy with the performance.

Structure, Material, Form

When working with sounds and collaborating with spaces, the spaces reveal certain characteristics of the sounds that are usually ‘hidden’. There are several layers in one sound, clusters of frequencies, even parallel and co-existing tactile sonic qualities, such as ‘soft’ and ‘rigid’. Singular sonic entities are themselves composed, they are sonic amalgamations or molecules made up from smaller nucleus sonic material.

I see sound as a relational shapeshifter. Through interaction sound changes its body. With these complex sounds in dialogue with the space, I develop a structure, a sonic scenography, that can be entered and that reveals its form over time. The structure can best be compared with a four-dimensional network. Change and stability allow this relational system to thrive. The balance of both is important. When there is too much change, there will be chaos. If there is too little change the system will stagnate. The combination of connection and freedom allows for a living physical presence in the spatial sound performance.

Precision and Freedom

My spatial compositions seek out balances between the recognizable and the familiar and the new and unexpected.

The product of my work is a process. The piece is an open work that allows for, or rather anticipates, change. This creates a certain kind of presence and attention, close to the state in which we play games, or are in an intense conversation. All senses are active. We are alert in the most positive way.

A stable framework and precise tools give stability. The paths are flexible. Inside of each element is a plasticity. There is a framework which can stretch and bend. It can be disrupted temporarily but it is important that it is not shattered or broken. When it loses its connections, the fragments have no stability. Without their relations randomness will occur.

In his book on 20th century composition, Komposition im 20. Jahrhundert, Walter Gieseler states that structure is important for the composer in order to create “the architecture of his sound-building, for the statics of his sound image”, (Gieseler, 1975, p.7). According to him, structure is not only a way for the composer to organise sounds but something that needs to be perceivable for the listener to be able to guide the audience’s journey. In my work structure is important for me as composer, and often also for the collaboration partners in the collective construction and navigation of the work. I trust that I can make the structure perceptible for the audience too. However, this does not mean that I want to make the structure evident. Structures are created to support something, and that something is what can be experienced. As the audience moves through the structure (or several structures), the structures are being de- and re-composed. Sonic forms emerge on different time scales that form different experiences. I use the word form here both as an expression for the sonic shapes and patterns that emerge, and as a verb that gives temporality to this emergence that is a process which can be experienced.

Building with Sound - Placing Sound - Sonic Scenography

Sonic scenography needs to be constructed. It is not found. Building with sounds resembles the construction of buildings to a certain extent: sonic structures and forms reach a temporary stability and can be entered by the audience. Composing space with sounds can also be compared to olfactory architecture. Similar to a perfume, where the top note stimulates a subtly different reaction to the lower note, the different sound elements call for peculiar attention, and this changes over time. The creation of sonic scenography is a production of multisensorial spaces that are both dynamic and processual. The way each element of the spatial sound composition dwells in the space reveals its character, and its interaction with the space simultaneously makes it characteristic of (or ‘native to’) the space. The elements together create the sonic architecture. In that way structures are created that hold possibilities for support and tension, and change. The more elaborate these structures become, the more connections arise. At the same time, as they are temporary structures, connections continuously appear and vanish. The interactions each sound has with its surroundings are therefore expansive.

All elements that I need in sonic scenography are already existent in some energetic or material form when I share the space with the performers. I need to initiate a process that unites them towards a specific and open scenography. Substance needs to be put into vibration, airflow needs to be controlled, the acoustics of the space need to be activated so they can reveal themselves in their response. Sonic scenography develops during a performance. It cannot be static. It is alive and dynamic.

The placement of sounds in the space situates them and lets them spread in space and time. This can be done by placing the instrumentalists at the same spot as their sound or giving an instrumentalist a clear description of where to place/direct the sound from a distance. The placement is selected based on how the sound can be in the space, with a unique expression in the moment, and in interaction with the acoustic qualities of the space over time. The placement is also always in relation to the other sounds in the space and is in anticipation of their interaction. It is a distribution in space and a negotiation of space. Sometimes I see this positioning as a ‘seeding’, in that the way it can grow is partly known and partly unknown.

Thoughts on notation

My works are site-sensitive and specific to the people I work with. When contemplating notation one of the main questions is “Who is it for?”. In the case of my works, a particular work will not be repeated outside of its original context. The score only needs to communicate to the performers of the piece and to myself. It exists to help our dialogue in the final phase of the creative process. I feel that the notation naturally becomes project-specific. Many times, the source of inspiration and the creative process are still evident in its design.

However, not repeating a piece at a different site does not mean that it ends with the last performance on-site. As the form is an open work, a piece is also open and able to be adjusted to different situations. It is, however, of utter importance that the situation retains priority over the score. The selection and the development process only occur on site with local participants, after an introductory workshop.

The only piece that has been restaged during my research is Voiceland. It was repeated in Reykjavik in 2018 with the same choir that performed it in Akureyri in 2017. Almost all the movements and placements of the sounds and performers had to be changed. As the placement and movements were noted in the original score, the score had to be adjusted accordingly.

After- and further- thoughts

Spatial Musical Thinking

- Thinking in space and time

The interrelation between space and time is the basis for composing in space. As the performance involves humans as performers and audience, considering the perception of space and time is important. My writing and thinking here is informed by my working with space-time and my experiencing of it in my practice. Working with the idea of the music of the universe in Musica Munda (2018) and Musica Mundana (2020 -) has led to me look further into theories around space and time. These speculations serve as inspiration for how to compose in space in general and particularly for Musica Mundana. (For a visual impression please follow this link to the artistic projects)

When we share a space, this does not consequently mean that we share the same time. But since we experience time in relation to different elements (how we feel, where we are, the speed of that which surrounds us, etc.) we could say that we are all in different time-places when we share a space.

Over the past years, I have learned that spaces have their own temporality. Space-specific time is shaped by the architecture, volume (by which I mean the capacity of a space and its dimensions) and materials of the space. In my musical work this becomes evident in echoes, delays and reverberation as well as other ways the space reacts to different sounds, like frequency-dependent absorption and reflection. The temporality of a space may demand a certain timing and rhythm. The space therefore structures time, or at least our experience of it. The sonic space I create in my work is dependent on the architectural space. With its specific acoustics the space allows for certain temporalities.

Music depends on a temporal organisation of sonic events. I believe that time can be shaped and formed. Experiential time appears malleable. It can be expanded or compressed. In his book Raum-Zeit (Space-Time) Martin Carrier explains that in the philosophy of space-time it comes down to the question of if one believes that time and space are absolute or if they are relational (Carrier, 2009, p.6). As sound is an ephemeral material that is always in relation, I work with time and space as relational forms. As I describe in my texts Architecture and Music and The space inside music and the music inside space, even if I consider architectural spaces as temporarily fixed, there are other spaces - like sonic space and social space that are also examples of relational spaces. Similarly, I see the construction of spatial sound compositions as an expression for time as a relational dimension.

Physicist Carlo Rovelli says in his book The Order of Time that “the temporal structure of the world is more complex than a simple linear succession of instants” (Rovelli, 2018, p.97). My artistic practice is my way of trying to understand the world we live in. In the past three years I have expanded this question towards the universe (Musica Munda and Musica Mundana) where the

practical artistic exploration of the temporal complexity mentioned by Rovelli engages the body of sound and gives corporal experience of spatial temporalities.(see The Body of Sound in dictionary and as book)

Space can give attention to time. We experience time through movement in space. When sound travels in a space, it changes. The change of the sound becomes evident over time and in space. This change in turn therefore reveals the temporality of the space.

When I work practically with the exploration of space-time, I pay particular attention to the intra-actions between sounds and spatial elements. They offer another temporal layer than the direct sounds created by the musicians. These intra-actions relate to Karen Barad’s ‘mattering of the world’ that is an ongoing open process that “acquires meaning and form in the realization of different agential possibilities” (Barad, 2003, p. 817).

Additionally, if a spatiotemporal unfolding of music can be experienced from within the spatial music, with the freedom to move in relation, our experience of time can be altered. Herein, by varying the positions of the musicians and therein the distance to the audience, spatial and therein acoustic relations to sonic events are altered. The temporalities that are created by the musicians in the conscious shaping of sounds with the anticipation of the sound’s journey, shapes temporal structures that are fluid. When giving the audience the possibility to move inside this sonic space, they therefore also move through time.

Sound has several ways of engaging us and our senses. Spatial musical performance engages the whole body with its multiple senses that transmit different information simultaneously in this spatiotemporal landing. Landing in my artistic research project is an active and dynamic creation of sound-lands, a continuous arriving in an immediate surrounding. It does not have the distance of sound- and landscape. Landing is the creation of topography in proximity. This also relates to Donna Haraway’s understanding of ‘worlding’ within SF (science fiction, or speculative fabulation) where it is "storytelling and fact telling; it is the patterning of possible worlds and possible times, material-semiotic worlds, gone, here, and yet to come" (Haraway, 2016, p. 31). Landing is a mattering with humans and non-humans, with matter and the so-called immaterial (the air and sound). The embodied experience of these ever-changing sonic scenographies in interaction is simultaneously a listening participation (Böhme and Engels-Schwarzpaul, 2018, p.130) in spatial musical performance. (see landing in the dictionary)

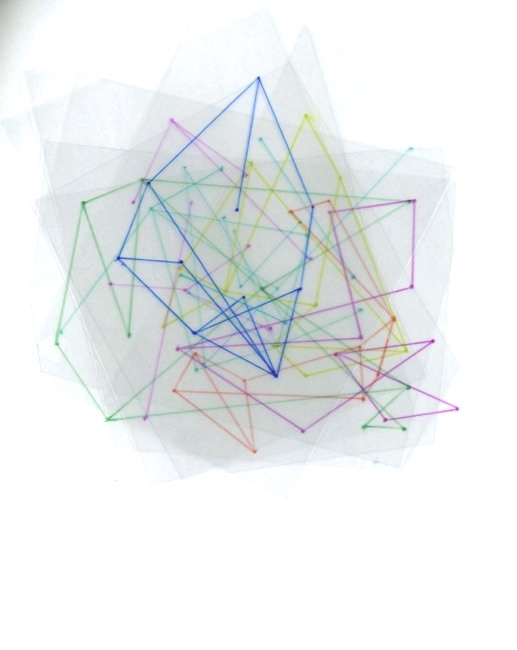

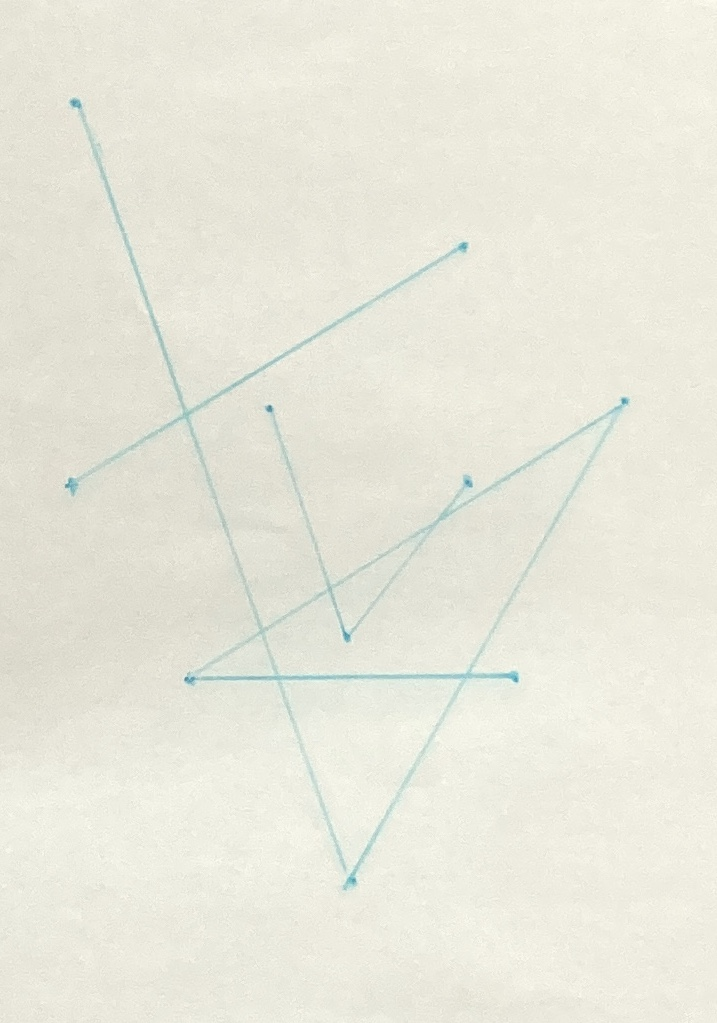

This sketch shows examples of individual connections. These can be connections from performer to performer but also from performer to other co-creators such as sound, space and audience.

This image is an example of a vulnerable net. Some connections are singular. This could mean that when it is interrupted the co-relation is lost. However, since the connections shift over time the performer can move towards the next connection(s) and will be reconnected to the network.

The music dances around the audience

jointly with the instrumentalists

vibrating with spatial elements

revealing surfaces and structures

expanding beyond the visible

inviting the audience

to join the dance

as an experiencer

as an explorer

who carefully enters a foreign

and yet familiar microcosm.

The other

outside

finds recognition

inside.

Interprets all signals

in relation to experiences

had before.

Expanding

and connecting

memory

with this present sensual experience.