The biggest difference found related to tempo is in the second movement. The Primrose version is the fastest recording made ever (quarter note=154). His good ability of the fast tempo is just amazing because it denotes an evident virtuosity. Undoubtedly, he achieved a virtuoso performance of Walton's work. However, I think it is a little bit exaggerated and makes me wonder if it is worth the demonstration of speed and virtuosity. This provokes a restless feeling when listening to it.

“The movement begins to sound like a fast race just for the sake of speed itself, instead of the playful but significant interplay of musical ideas that Walton created. This represents, in the spirit of the times in which it was recorded, a performer’s demonstration of the virtuosic technique above all other considerations1”.

It is also noteworthy that Riddle's tempo is quite fast (quarter note=132) since in the first orchestration version of the Concerto the tempo marked in the score is 116 per quarter note.

3.2.3 Tempo marks

Related to tempo, there are also some differences in some movements.

|

|

FIRST RECORDING (F. RIDDLE) |

SECOND RECORDING (W. PRIMROSE) |

|

1st Movt. |

22. Bar 46: quarter note=100 |

22. Bar 46: quarter note=115 |

|

|

23. Bar 81: quarter note=80 |

23. Bar 81: quarter note=90 |

|

|

24. Bar 104: quarter note=120 |

24. Bar 104: quarter note=138 |

|

2nd Movt. |

25. Quarter note=132 |

25. Quarter note=154 |

|

|

|

|

In general terms, Riddle's tempos are slow throughout the first movement. He tends to start the semiquavers from bars 46 and 104 slower than what is written in the score. This is a good resource to emphasize more the stringendo by levels up to the culmination of bar 52 (con spirito).

Example 22. William Walton, Concerto for viola and orchestra, edited by Oxford University Press, 1st movement, bars 46-52.

An orchestration detail on Riddle's recording is the sixths from bar 82 onwards. These double stops, which have a very high level of difficulty, are almost covered by the winds. This may be due to some extent to the technical limitations and recording quality of the time. In general terms, the exquisite orchestration never covers the solo viola part:

“The concerto is a marvel of orchestral poise; the orchestra never impinges on the soloist’s both melancholy and muted voice2”.

The second one is an intonation mistake. In bar 275, he plays the C sharp too out of tune, almost like a C natural.

3.2.5 Another considerations

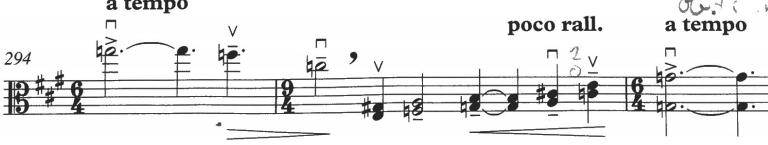

Special mention should be made of some differences in interpretation. For example, at the end of the third movement, at bar 295. Primrose plays these double stops with a lot of portamento, although it is used tastefully. With these details added to his performance, he creates an individual and original interpretation of Walton's Concerto.

I also find it interesting to comment anecdotally on two small mistakes in Primrose's recording, both in the third movement. The first, in bar 89, he plays the Bb one-quarter note later.

3.2.4 Fingerings

In relation to different fingerings, there are not too many differences. This is the category in which both performers agree the most. Nevertheless, the fact that there are not many different fingerings does not mean that they use them in the same way. Both have their own expressive resources to emphasize a fingering and make it special, such as vibrato, for example.

There is a clear and relevant example of different fingerings in the second movement of the Concerto. In bars 46 and 47, Primrose plays those quavers in the first position, in a simple and effective way. Riddle, on the other hand, plays it in a higher position, on the C string, thus achieving a different resonance and depth of sound. Without a doubt, it is a very interesting fingering.

Example 26. William Walton, Concerto for viola and orchestra, edited by Oxford University Press, 2nd movement, bars 46-47.

Example 28. William Walton, Concerto for viola and orchestra, edited by Oxford University Press, 1st movement, bars 82-92.

Example 27. William Walton, Concerto for viola and orchestra, edited by Oxford University Press, 3rd movement, bar 295.

Example 29. William Walton, Concerto for viola and orchestra, edited by Oxford University Press, 3rd movement, bar 89.

Example 30. William Walton, Concerto for viola and orchestra, edited by Oxford University Press, 3rd movement, bar 275.

3.3 Comparison with modern recordings

“As far as the history of the viola performance, the artistic and technical level of these early recordings is extraordinary, (…) The expressivity and compelling individuality of these recordings remain a towering achievement, unsurpassed to this day3”.

These two early versions of the Concerto are good examples of a Romantic and individualistic approach to performance. Nevertheless, after listening to later recordings by Yuri Bashmet (1994, with the London Symphony Orchestra), Paul Neubauer (2001, with the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra), Maxim Vengerov (2002, with the London Symphony Orchestra) or the most recent, Antoine Tamestit (2018, Frankfurt Radio Symphony), I became aware of the technical and interpretative changes that the Concerto acquired. While the early recordings were more concerned with tonal beauty, individualism, and virtuosity over technical perfection, the recent recordings show a greater homogeneity in terms of interpretative resources and do not take so many liberties.

“As a whole, modern artists take fewer liberties and sound more alike4”.

Some of these interpretative changes are the suppression of portamento as a resource (except in some ascending changes of position), and the addition of continuous vibrato in modern interpreters. In fact, Primrose's vibrato may be the interpretative element that most resembles that of a modern performer, because he makes continuous use of it. However, his way of using portamento would be considered old-fashioned today.

So, in conclusion, it is impressive to observe in the viola not only the technique, but also different interpretative approaches through the recordings of the first great Viola Concerto of the 20th century.

next