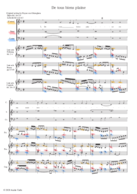

Analysis “De tous biens plaine”

About my comparative edition

We already have a great comparative edition by Young and analysis by Kieffer. However I would like to extend their work. They compared pieces with tenor line but I also put cantus and contra tenor line in my edition. From this, we can see clearly all the voices are there most of the time. In the Fribourg and Pesaro, the rhythmic sign is not as accurate as later sources. I refer to Young’s edition. It is always a problem how to transcribe the lute tablature to normal modern writing, because the tablature does not tell us how long each note should be therefore the voice leading will be guessed by transcriber. This time I try to write in three voices, interoperated based on original setting. Basically cantus is on the upper staff, Some middle voices between tenor and cantus is in the upper staff.

Tenor is in the lower staff but with stems up, the contra or some lower notes below is in the lower staff with stems down.

There are many sources for the original setting of “De tous biens plaine”, but in my comparative edition I used original mainly from Dijon Chansonnier which may be dated 1460’s - 1470’s and its identical source Leborde at same time in same area. They are written slightly simpler than later sources namely Petrucci’s Canti A (1501) and Bologna Q16 (1487-1490’s). Text placement is not clear in any source, so I refer to CMM for this. I chose to transcribe the original setting with original note values. For the tablature, the rhythm sign shows half of the note value, so usually ♪ is transcribed as a quarter-note. So in my edition, if the original setting has brevis, that is equal value to the semi brevis in lute settings. The very beginning of lute setting starts with some leading notes which comes from long instrumental tradition before, I didn’t count as bar 1. The bar 1 starts from the next bar.

There is a big error from bar 42 to bar 44, I would suggest that it is missing one minima in the first half of the bar 42 and again in bar 44 while Young suggested two minimas are missing between bar 44 and 45. I added some my suggested notes in my edition.

Texture

In the Fribourg and Pesaro, sometimes they have big chords, so the number of the voices are inconsistent not like intabulation style. This comes from plectrum playing like we can see in Wolfenbüttel. With the plectrum, the player can only pluck one string or the strings sitting which are next each other. If the strings are apart, the player either needs to use fingers (middle or/and ring) or fill in with notes on the middle strings. In Capirola, the number of voices are more consistent (3 voices most of the time), he didn’t fill in with chords.

Diminutions are clearly on one voice in one spot, and sometimes diminutions is linking the voices like bastarda style.

Lute idiomatic writing

Fribourgbar and Pesaro might have been played with plectrum. In Fribourg bar 13 and 31, the tenor is missing, it is probably because it was cantus and contra is too far, playing only two voices is easier than three voices with holding the plectrum. On the other hand, Pesaro in bar 31, contra is placed octave higher so all the three notes can be played with plectrum without using fingers. Same example in 23 in Pesaro, contra is changed to G instead of D probably because of this reason (or could be just a mistake). One more reason that I assume this piece in Pesaro was played by plectrum is bar 8, the syncopated rhythm seems unnecessary. But if you look at the Wolfenbüttel lute manuscript, in order to play with plectrum all the voice, the voice is played separately but not at same time, so the result of this is syncopated rhythm. But if the Fribourg was played with plectrum, bar 21 with four notes chord with ‘m’ in the middle is a mystery how they manage. Probably they pluck with plectrum two low notes and somehow manage to mute the middle notes as noted, and pluck upper two notes with fingers.

In Fribourg bar 17, the diminution goes high, left hand position is higher than other place to play 7th flet (note D). Actually this is a good spot to go high because both of the tenor and contra is G (contra is octave lower than tenor), contra’s G is open string which has diapason string (octave higher) can sound tenor part. This D note is linked by descending diminution, passed to tenor and go through the contra, and reaches to the lowest note of the lute! This gimmick is made with simple notes and easy playing technique but it certainly gives a good effect.

Correspondence

It is interesting to see that actually three lute solo sources look similar but not same. Diminutions are on the same place and same voice. Furthermore, even the shape of the diminutions are same sometimes. Like bar 1, descending from G to low G, bar 2, descending diminutions on cantus, and ascending in bar 3. Also linking from bar 6 to 7 with the diminutions BAGA with semi fusa (16th notes) but Capirola’s version is more well-planned, he made a conversation between diminution on tenor and cantus in same bar. Ascending diminution with fusa (8th notes) bar 11. However, accidental can be varied (like bar 1). The interesting spot is bar 12, all of the three lute setting has the diminution A BAGA but in Fribourg, it’s placed one minima later than the other two sources. Same thing happens in bar 35 and 36, the common dimunution CDEF is placed on different beat in Fribourg and Pesaro. Another interesting example is bar 25, Fribourg and Pesaro have similar diminutions starts from D in the second half of the bar, but while Fribourg has DB, Pesaro has DA, which makes sense from the harmony on D of the each versions. This D is not included in original setting. One more example is in bar 28-29, when the tradition of A part to B part of rondeau form, in Capirola the descending notes starts earlier than the original setting and goes up with cantus as 10th parallel. That happens same for Fribourg, in this case it is difficult to say because of the non definitive rhythm signs, but the Capirola’s version could support this interpretation and it seems no any other good options.

From these feature I mentioned above, it is clear that these three sources are not copied by seeing one or another but it might have been transmitted by playing and by listening.

Diminution

Diminutions are clearly on one voice in one spot, and sometimes diminutions is linking the voices like bastarda style.

Measure 7,8: in Fribourg the Tenor is missing, it made me think that probably it was played with plectrum, the scriber chose contra tenor and cantus, tenor is just octave higher than contra. Because lute has diapason string, you can here octave higher without plucking middle C. On the other hand, Pesaro chose different note for contra, filling the notes between contra and cantus to manage play the tenor. Capirola has more virtuosic passages in bar 32, 47-48 and 55-58. When he put such diminutions, it’s often like bastarda style and focused on diminutions without plucking much notes besides them.

Rhythmic arrangement

Because lute’s sound does not stay longer, the notes are often re-plucked. Sometimes, they are not re-plucked with two simple minimas but played with rhythms. The good example of this is in Fribourg is bar 13 in contra, bar 28 in cantus. Similar things in Pesaro, bar 5, bar 24 but with octave jump, bar 42 also tenor jumps octave lower, bar 49 and 50. This repeated note or octave-jump-note fills some space which could be awkward moment. In Capirola, he plays with bit more complicated rhythms like bar 7. What he does in bar 15 and 16 is brilliant idea, this makes this version very unique. Capirola consciously try to vary the rhythms. With syncopated rhythm, we can see that besides I mentioned above in bar 3, bar 25-26, bar 37 and bar 45. And in bar 52 the diminution is divided in three in a minima. This kind of changing of the division (2 or 3) is mentioned by Blindhamer or appears in the poem that described Pietrobono.

Harmonic arrangement and accidental

Most of the time, all the three voices are there in the lute settings but if there is some change, that would be the contra tenor part. Bar 45 is good example for this, Pesaro didn not take B flat for the contra but chose F instead. This makes the harmony changes, A is added for this change. Another example in Fribourg is bar 52, E flat is added in the bottom and the middle, so harmony is different from Pesaro which has D. Another example is bar 11, Pesaro put G above the contra. This kind of harmonic change is also appeared in later lute intabulation like Crema or Bianchini in 1540’s.

Another conscious harmonic change happens in bar 55. in the second half of the bar, cantus’s F and contra’s G should crush but Pesaro and Capirola avoid this crush in the same way which cantus plays G as well as contra. Fribourg’s top note is but also G is played in the middle.

Unlike the mensural notation, lute tablature can notate the exact note which means player does not have to choose musica ficta. There are some difference in these three lute sources in bar 10, bar 21, bar 34. Which shows us that musica ficta is not something has a definite answer but it is depending on the player’s tastes or feeling of the day.