In my opinion, this music sounds as it could have been extemporized at the piano and then notated later. The repetitive five-note ascending figuration, each five-note group beginning with a half-step, is accompanied by an attempt to harmonize the material. It seems likely that Schumann stumbled upon this figuration while playing the piano, and then spent time and effort attempting to harmonize and contextualize it.

Although nowhere near identical, this figurative material reminds me of the material that Schumann composed for his character piece Eusebius, from the cycle Carnaval, Op. 9. The quintuplets in the sketch above have a similarly asymmetric character to the septuplets in Eusebius, and furthermore, the half-step delay of the consonant tone is apparent in both.

This association I have made between the extemporized sketch and Eusebius (described as improvisation5 in the chapter On Scales of Improvisation) allows me to define the rules and framework for Eusebius Traum: replace Schumann's composed right-hand figurations in Eusebius with more improvised material inspired by the contents of the sketch.

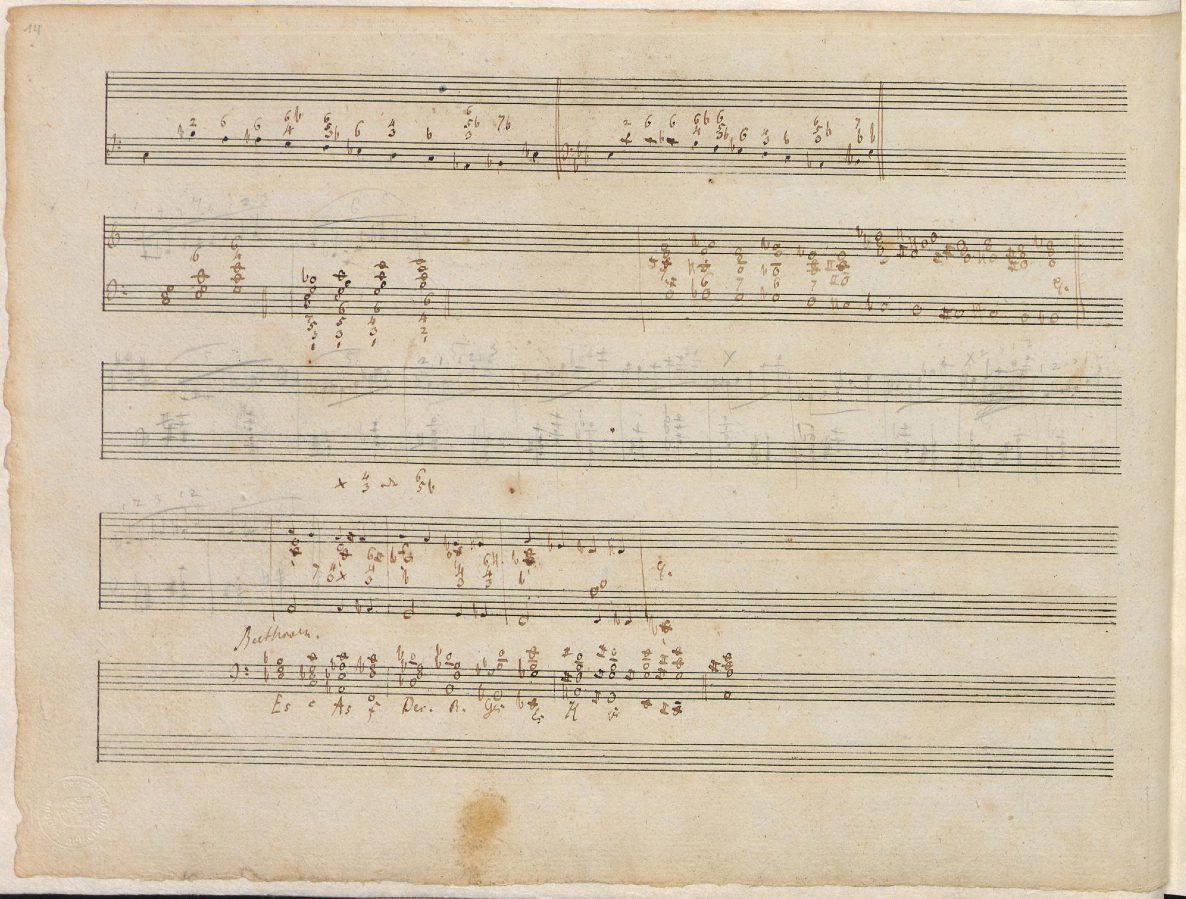

This page from Schumann's first sketchbook (Skizzenbuch I, 14) is described by the cataloger as including "not identifiable sketches and/or compositional fragments with an allusion to a work of Beethoven." (See the bottom line of the sketchbook page for the allusion to Beethoven – Schumann seems to have transcribed a harmonized series of descending thirds and then alluded to Beethoven as the source). However, more applicable to Eusebius Traum are the harmonized figurations written down very lightly, perhaps in pencil – see the third and fourth staves on the page. An engraved version of this notated material can be seen here below, from the Schott Edition of the Schumann sketchbooks:

Eusebius Traum (third instance)

Recorded live at the University of Oxford (Oxford, UK) on September 9th, 2014

Eusebius Traum (second instance)

Recorded live at the Orpheus Instituut (Ghent, Belgium) on December 13th, 2013

Eusebius Traum (first instance)

Recorded live at the Musikakademie (Basel, Switzerland) on October 29th, 2013

[0:04] So it seems I have set up a sort of imitation game.

[0:17] The upper voice remains silent during this fourth bar (as understood in relation to the figured-bass score).

[0:35] Some of the voice-leading in this second phrase is strange, but I like the canon of Ab-G-F-Eb that ends the phrase in two different speeds, one twice as fast as the other.

[0:49] This phrase turns out to have just one melodic line but with repeated notes.

[1:05] I particularly like the static Eb that remains in the middle range of this last phrase.

[1:25] The two-voice imitation returns in this climactic moment – I would prefer if the last high-voice entry (C to Bb) were a bit more pronounced. It seems like I gave up on the low-register version of the reprise of the first phrase, i.e. I left out bars 21-24 and replaced them with bars 29-32 in the figured-bass score.

[1:34] The only logical place for the prominent mid-range C to resolve would be a D (one step higher), but this does not happen.

[1:49] Now I could envision one more entry of the higher voice (for example, Bb up to high Eb) but that does not happen.

[1:52] By ending the piece here, I also left out bars 25-28, thus turning this version of Eusebius Traum into a 24-bar piece.

This instance of Eusebius Traum contains no melodic material that could be heard as referencing the sketch here to the left; and so therefore, in a strict sense, does not fulfill the initial conditions that were drawn in order to create versions of the piece.

[0:01] This instance of Eusebius Traum starts on almost the same pitches as Eusebius from Carnaval.

[0:18] The first phrase could be summarized as follows: the voice-leading is fine, but any semblance of rhythm is tangible only through the harmonic tension.

[0:22] The reach down to the lower E unexpectedly extends the melodic range.

[0:25] Leaving this C# unresolved sounds like a mistake.

[0:29] Perhaps this is why I slightly accented this D?

[0:54] Until now, the performance is relatively sparse with a maximum of three-voice counterpoint being utilized. This moment corresponds to the end of bar 16 in the figured-bass score.

[0:59] With these five melodic tones, I establish expectations that the melodic material will start to happen in two different registers.

[1:07] Both registers are more or less melodically functional, although the lower register is less interesting than the upper.

[1:16] This performance of parallel octaves (the high D resolves to an Eb while the low D also resolves to an Eb) transgresses the classic voice-leading rule of avoiding such parallels.

[1:19] Ending on an open fifth here is a bit disappointing.

[1:30] This exposure of two A's at the same time sounds risky but is then resolved appropriately.

[1:48] The Eb resolution is barely audible, but it is there.

[1:50] The original piece stops here – I believe it was also my intention to stop here, but at the last minute I wanted a chance to try the last phrase again.

[2:12] I played another hardly audible high Eb here, and ending on an open fifth (Eb-Bb) is not harmonically ideal.

[2:15] This last phrase is an extra eight-bar phrase not included in the figured-bass score, thus making this version of Eusebius Traum a 40-bar piece, rather than the original 32.

[0:00] I seem to like to start Eusebius Traum with dissynchronous piano playing, i.e. that the left and right hand do not attack their respective first tones together.

[0:12] The low F# in the melody line sticks out a bit too much dynamically.

[0:26] The dissonance between the high Ab and the lower A is a bit too extreme in this context.

[0:32–0:58] There is a vague attempt here to realize two clear melodic lines but neither of them really manage an entire melodic gesture (except perhaps [0'40"-0'43"] in the lower line).

[1:00–1:12] The melodic shape never takes off clearly in one direction or another.

[1:20–1:28] This is an example of how a melody can find direction and take clearer shape.

[1:54] The final tone is well played.